Licensing: the Sequel Part 1 of 2 Suffolk University Law School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

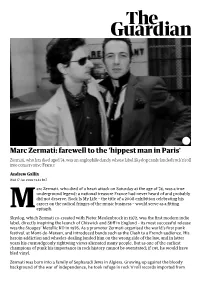

Marc Zermati

Marc Zermati: farewell to the 'hippest man in Paris' Zermati, who has died aged 74, was an anglophile dandy whose label Skydog crashlanded rock’n’roll into conservative France Andrew Gallix Wed 17 Jun 2020 13.42 BST arc Zermati, who died of a heart attack on Saturday at the age of 74, was a true underground legend: a national treasure France had never heard of and probably did not deserve. Rock Is My Life – the title of a 2008 exhibition celebrating his career on the radical fringes of the music business – would serve as a fitting M epitaph. Skydog, which Zermati co-created with Pieter Meulenbrock in 1972, was the first modern indie label, directly inspiring the launch of Chiswick and Stiff in England – its most successful release was the Stooges’ Metallic KO in 1976. As a promoter Zermati organised the world’s first punk festival, at Mont-de-Marsan, and introduced bands such as the Clash to a French audience. His heroin addiction and wheeler-dealing landed him on the wrong side of the law, and in latter years his curmudgeonly rightwing views alienated many people. But as one of the earliest champions of punk his importance in rock history cannot be overstated; if cut, he would have bled vinyl. Zermati was born into a family of Sepharadi Jews in Algiers. Growing up against the bloody background of the war of independence, he took refuge in rock’n’roll records imported from the US, which were more readily available – as he often boasted – than in metropolitan France. Like so many other pieds-noirs (the name given to people of European origin born in Algeria under French rule) the family fled to la métropole in 1962, when the country gained independence. -

Affordant Chord Transitions in Selected Guitar-Driven Popular Music

Affordant Chord Transitions in Selected Guitar-Driven Popular Music Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gary Yim, B.Mus. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: David Huron, Advisor Marc Ainger Graeme Boone Copyright by Gary Yim 2011 Abstract It is proposed that two different harmonic systems govern the sequences of chords in popular music: affordant harmony and functional harmony. Affordant chord transitions favor chords and chord transitions that minimize technical difficulty when performed on the guitar, while functional chord transitions favor chords and chord transitions based on a chord's harmonic function within a key. A corpus analysis is used to compare the two harmonic systems in influencing chord transitions, by encoding each song in two different ways. Songs in the corpus are encoded with their absolute chord names (such as “Cm”) to best represent affordant factors in the chord transitions. These same songs are also encoded with their Roman numerals to represent functional factors in the chord transitions. The total entropy within the corpus for both encodings are calculated, and it is argued that the encoding with the lower entropy value corresponds with a harmonic system that more greatly influences the chord transitions. It is predicted that affordant chord transitions play a greater role than functional harmony, and therefore a lower entropy value for the letter-name encoding is expected. But, contrary to expectations, a lower entropy value for the Roman numeral encoding was found. Thus, the results are not consistent with the hypothesis that affordant chord transitions play a greater role than functional chord transitions. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 95 OCTOBER 7TH, 2019 Welcome to Copper #95! This is being written on October 4th---or 10/4, in US notation. That made me recall one of my former lives, many years and many pounds ago: I was a UPS driver. One thing I learned from the over-the- road drivers was that the popular version of CB-speak, "10-4, good buddy" was not generally used by drivers, as it meant something other than just, "hi, my friend". The proper and socially-acceptable term was "10-4, good neighbor." See? You never know what you'll learn here. In #95, Professor Larry Schenbeck takes a look at the mysteries of timbre---and no, that's not pronounced like a lumberjack's call; Dan Schwartz returns to a serious subject --unfortunately; Richard Murison goes on a sea voyage; Roy Hall pays a bittersweet visit to Cuba; Anne E. Johnson’s Off the Charts looks at the long and mostly-wonderful career of Leon Russell; J.I. Agnew explains how machine screws brought us sound recording; Bob Wood continues wit his True-Life Radio Tales; Woody Woodward continues his series on Jeff Beck; Anne’s Trading Eights brings us classic cuts from Miles Davis; Tom Gibbs is back to batting .800 in his record reviews; and I get to the bottom of things in The Audio Cynic, and examine direct some off-the-wall turntables in Vintage Whine. Copper #95 wraps up with Charles Rodrigues on extreme room treatment, and a lovely Parting Shot from my globe-trotting son, Will Leebens. -

Universal Music Tribe - Iggy & the Sto… Site Map Contact

3/29/2011 Universal Music Tribe - Iggy & The Sto… site map contact Home Buffalo Zone News Features Video Downloads Radio About Us Contact Advertise Share | Iggy & The Stooges - Raw Power Live Iggy & The Stooges Raw Power Live In The Hands of The Fans (MVD) The original punk Iggy Pop is alive and well and at the age of 63 he is still a force to be reckoned with. Recreating the classic album Raw Power live onstage some 38 years after it was released, the reformed Stooges' (Iggy Pop, Scott Asheton, James Williamson, Steve Mackay, Mike Watt) performance at the All Tomorrow's Parties Festival on Friday, September 3, 2010 is high energy, balls to the wall, mayhem- just like it was back in in ‘73. From “Raw Power” to “Search and Destroy” and “Your Pretty Face is Going to Hell,” The Stooges recreate the original songs flawlessly. It’s enough to make Lester Bands rise from the grave and dance a jig. Released on 180 Gram Vinyl, the album is a real collector’s item and makes a good companion piece to your original Raw Power LP. The LP will be officially release on Record Store Day, April 26, 2011, so get your yah yahs out and get ready to rock, bitches. - Michael Buffalo Smith universalmusictribe.com/iggy___the_st… 1/2 3/29/2011 Universal Music Tribe - Iggy & The Sto… Home Buffalo Zone News Features Video Downloads Radio About Us Contact Advertise Site Mailing List UNIVERSAL MUSIC TRIBE 1813 North Main Street Greenville, SC 29609 Email: [email protected] This website designed using the iBui.lt website builder universalmusictribe.com/iggy___the_st… 2/2. -

EFG London Jazz Festival at the Barbican Friday 15 – Sunday 24 November 2019

11 October 2019 EFG London Jazz Festival at the Barbican Friday 15 – Sunday 24 November 2019 Featured artists across the festival at the Barbican include: Nik Bärtsch, Sophie Clements, Cécile McLorin Salvant, Sullivan Fortner, The McCormack & Yarde Duo, Herbie Hancock, Iggy Pop, Eliane Elias, Vinícius Cantuária, The Art Ensemble of Chicago, Junius Paul, Dudu Kouate, Abel Selaocoe, Michael Wollny, Wolfgang Heisig, Emile Parisien, Leafcutter John, Max Stadtfeld, Dawn of Midi, Daniel Brandt, O-Janà, Hobby Horse, Tomorrow’s Warriors, LUME and Bitches Brew The annual EFG London Jazz Festival – produced by Barbican Associate Producer Serious – comprises hundreds of concerts and gigs across London, celebrating the ever-influential body of work of jazz giants and their ongoing legacies and giving profile to the fresh voices of the scene. As one of the festival’s major venues, the Barbican presents a cross-section of concerts alongside a programme of film screenings and FreeStage events. Highlights of the EFG London Jazz Festival 2019 at the Barbican include: • Pianist and composer Nik Bärtsch and visual artist Sophie Clements present the UK premiere of their striking new collaborative audio-visual performance When The Clouds Clear, a meditation on elemental forces and cycles, featuring amplified solo piano, sculpture, film and installation design (Fri 15 Nov) • Legendary American jazz pianist Herbie Hancock makes two festival appearances alongside his band – in a solo show (Sun 17 Nov) and in a collaborative performance together with the Los Angeles -

WDR 3 Open Sounds

Musikliste WDR 3 Open Sounds Iggy Pop 70 Zwischen Proto-Punk und Post-Chanson Eine Sendung von Thomas Mense Redaktion Markus Heuger 22.04.2017, 22:04 Uhr Webseite: www1.wdr.de/radio/wdr3/programm/sendungen/wdr3-open-sounds/index.html // Email: akustische.kunst(at)wdr.de 1. Main Street Eyes K/T: Iggy Pop (James Osterberg Music/Bug Music BMI 1990) CD: Brick By Brick, 1990, Virgin Länge: 3.02 Minuten 2. 1969 K: James Osterberg (Iggy Pop)/ Ron Asheton, 1969 CD: The Stooges, 1988 Elektra/Asylum Records, LC 0192 Länge: 0.53 3. Search and Destroy K: Iggy Pop/ James Williamson, 1973 I: Iggy and The Stooges CD: Iggy And The Stooges: Raw Power, 1973, 1997 Sony Entertainment LC 0162 Länge: 0.42 5. I wanna live K: Iggy Pop/ Whitey Kirst CD: Iggy Pop: Naughty Little Doggie, 1996, Virgin 1996, LC 3098 Länge: 0.12 6. I wanna be your dog K/T: Pop/ Scott Asheton/ Ron Asheton/ Dave Alexander CD: The Stooges, 1969/1988 Elektra/Asylum LC 0192 Länge: 1.12 WDR 3 Open Sounds // Musikliste // 1 7. Penetration K/T: Iggy Pop/James Williamson CD: Iggy And The Stooges: Raw Power, 1973, 1997 Sony Entertainment LC 0162 Länge: 2.30 8 . Dirt K/T: Iggy Pop/ Ron Asheton/ Scott Asheton CS. Funhouse, 1988 Elektra/ Asylum Records, LC 0192 Länge: 2.55 9. Gimme danger K:T. Iggy Pop/ James Williamson CD: Iggy And The Stooges: Raw Power, 1973, 1997 Sony Entertainment LC 0162 Länge:2.35 10. Nightclubbing K/T: David Bowie/Iggy Pop James Osterberg Music/Bewlay Bros.s:A.R.L./Fleur Music CD: Iggy Pop-The Idiot, Virgin Records 1990,077778615224 Länge: 1.00 11. -

The Legendary Stooges Axeman, 1948-2009: He Didn't Just Play the Guitar

The legendary Stooges axeman, 1948-2009: he didn't just play the guitar. BY TIM "NAPALM" STEGALL The first thing you noticed, after seeing the perfect picture of teenage delinquency in quartet form on the cover (and how much the band depicted resembles a prehistoric Ramones, if you're of a certain age), was the sound: Corrosive, brittle, brassy, seemingly untamed. It was the sound of an electric guitar being punished more than played. And the noise got particularly nasty once Mr. Guitar Flogger stepped on his wah-wah pedal. Because unlike whenever Jimi Hendrix stepped on a wah, this guitar didn't talk. It snarled and spat and attacked like a cobra. As the six string engine that drove The Stooges, Ron Asheton didn't play guitar. He played the amp. And the fuzztone. And the wah-wah pedal. In the process, he didn't just give singer Iggy Pop a sonic playground in which he could run riot and push the boundaries of then-acceptable rock stagecraft. ("Ron provided the ammo," says Rolling Stone Senior Writer David Fricke. "Iggy pulled the trigger.") Ron Asheton also changed the way rock 'n' roll was played and energized a few generations to pick up guitars themselves, creating several subgenres in the process. Ron Asheton was found dead in the wee hours of January 6, 2009, in the Ann Arbor home he and brother Scott (The Stooges' drummer) and sister Kathy (muse to a few late Sixties Detroit rockers and lyrical inspiration for The Stooges' classic "TV Eye") grew up in after the family relocated from the guitarist's native Washington, DC. -

“RON WAS the Riffmeister and All That Was Good in This World

“RON WAS THE Riffmeister and all that was good in this world,” declares Andrew Innes of Primal Scream, just one of countless bands who owe an inestimable debt to Ron Asheton’s (pictured, in glasses) monolithic stun guitar onslaughts on the first two Stooges albums. Asheton, found dead yesterday at his Ann Arbor home from a suspected heart attack, was the most influential punk guitarist of all time, his monosyllabic, piledriver riffs providing blueprints for later applecart- upsetters like the New York Dolls and Sex Pistols. Even former Captain Beefheart and Jeff Buckley guitarist Gary Lucas has paid tribute to “some of the best and most iconic riffs in punk history”. In his own private world Asheton, whose unusual pantheon of heroes included Adolf Hitler and the Three Stooges, was the most dangerous embodiment of the Stooges’ dum dum boys aesthetic, infamous for his extensive collection of Nazi memorabilia and the unsavoury swastika armbands later adopted by UK punk- shockers. Ironically, he was the only Stooge who eschewed hard drugs. Ron was born in Washington DC in 1948, brought to Ann Arbor by his mother after his Marine Corp pilot father Ronald’s death in 1963. Besotted by the Beatles and the Stones, he became obsessed with Pete Townshend after a Who gig during a mid-’60s pilgrimage to London with high school buddy Dave Alexander. He played bass in local bands including the Prime Movers, Chosen Few and Dirty Shames before forming the Psychedelic Stooges with Alexander, Scott and a local kid he’d met called James Osterberg – rechristened Iggy after a stint in a band called The Iguanas. -

Book < Mike Watt: on and Off Bass # Download

Mike Watt: on and off Bass « PDF \ BDU5DBWJNO Mike W att: on and off Bass By Mike Watt Three Rooms Press. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Mike Watt: on and off Bass, Mike Watt, The New Yorker calls it "unusual and beautiful." The LA Weekly raves, "the photos are strikingly inventive, revealing yet another side of this modern-day Renaissance man." MTV calls it "a charming, well-shot document of a the legendary punk rocker's photographic dabbling." Detroit Metrotimes: "A unique insight into Watt's mind." "Mike Watt: On and Off Bass" is getting a lot of buzz. And for good reason, considering the author and photographer is the legendary punk bassist himself. Mike Watt got his musical start thumping the bass with legendary San Pedro punk trio, The Minutemen in 1980 and he has been at it ever since. Over the years, he's toured with Dos, fIREHOSE, his own The Black Gang, The Secondmen, The Missingmen, and others, and he has worked bass as a sideman for Porno for Pyros, J Mascis and the Fog, as well as punk godfathers The Stooges. Off the road, at his beloved San Pedro, CA home base, Watt developed a deep interest in photography. In Spring 2010, Track 16 Gallery in Santa Monica, CA hosted an exhibit of his photos: "Mike Watt: Eye-Gifts... READ ONLINE [ 9.42 MB ] Reviews Extremely helpful to all type of folks. It is among the most awesome pdf i actually have study. I found out this pdf from my dad and i recommended this pdf to discover. -

Music Review: Iggy Pop Live in San Fran 1981

Music review: Iggy Pop Live In San Fran 1981 http://blogcritics.org/archives/2007/10/31/175007.php Blogcritics is an online magazine, a community of writers and readers from around the globe. Publisher: Eric Olsen REVIEW Music review: Iggy Pop Live In San Fran 1981 Written by Nik Dirga Published October 31, 2007 I love the guy, but the vast majority of Iggy Pop's studio CDs are rarely worth bothering with. Sure, he's made some stunning albums – his work with the Stooges, his David Bowie-produced classics Lust For Life and The Idiot, but the rest of his work can be all over the place, a few good tracks mired in with a bunch of dross. To get the real Iggy, to get that molten-metal heat that only Iggy Pop can summon up, you've got to go with the live albums. Iggy Pop boasts some fantastic live albums to his credit – the 1977 TV Eye Live, the unofficial Stooges live bootleg Metallic K.O., where you can actually hear the audience beginning to riot as Iggy struts, cusses and insults away at them. Now a show from 1981 joins the Iggy live parade, showing there's no Iggy quite like Iggy on stage. Iggy Pop Live In San Fran 1981 isn't quite as essential as some of the other Iggy live discs, but it's a heck of a lot of fun, summoning up the chaos of Pop's best live shows. The disc follows a DVD of the same show released a few years back. -

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Guitarist James Williamson Unites with Frank

ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME GUITARIST JAMES WILLIAMSON UNITES WITH FRANK MEYER AND PETRA HADEN AS ‘THE PINK HEARTS’ NEW ALBUM BEHIND THE SHADE IS WILLIAMSON’S MOST MUSICALLY EXPANSIVE PROJECT TO DATE, RUNNING THE GAMUT FROM INCENDIARY RAVE-UPS TO POIGNANT BALLADRY Certain to win support at Modern Rock and AAA Radio formats, Behind the Shade will be released on LP+CD, standalone CD, and digitally by Leopard Lady Records on Friday, June 22, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / March 21, 2018 — A 2010 inductee into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as a member of The Stooges, James Williamson is now set to make his most stylistically diverse musical statement to date with his new Group, James Williamson & the Pink Hearts. Fronted by Los AnGeles-based vocalists Frank Meyer (The Streetwalkin’ Cheetahs) and Petra Haden (That DoG, The Haden Triplets), the Pink Hearts’ repertoire encompasses everythinG from feral rockers to soul-searching balladry. Behind the Shade by James Williamson & the Pink Hearts will be released on LP+CD, standalone CD, and diGitally by Leopard Lady Records on Friday, June 22, 2018. Recorded last year in Berkeley (instrumentation) and Los AnGeles (vocals), Behind the Shade is a thorouGhly modern rock album which also evokes the most stirrinG elements of Seventies rock ‘n’ roll. “You Send Me Down” is an exuberant party starter with keyboards funky enouGh to have been lifted from the Billy Preston sonGbook, while “Pink Hearts Across the Sky” (a sure-fire favorite at AAA Radio) is resilient Americana with a crystal clear vocal performance by Haden worthy of Linda Ronstadt.