Psaudio Copper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Jeff Beck (From the 1991 Album BECKOLOGY VOL 2 / JEFF BECK GROUP ) Transcribed by Tone Jone's Words and Music by Don Nix Arranged by Jeff Beck

GOING DOWN As recorded by Jeff Beck (From the 1991 Album BECKOLOGY VOL 2 / JEFF BECK GROUP ) Transcribed by Tone Jone's Words and Music by Don Nix Arranged by Jeff Beck A Intro w/Piano B Band Enter's Moderate Rock = 90 P 1 V e Ie 4 U Gtr I Gtr.1 Jeff Beck (Distortion f T A 17 B 3 sl. 8va 8va 4 e P V V V j V V V l j j l V V V Ie z V V V V V u u Full 1/4 Full [[[[[ M M M [[[[[[[[[[[ 15 T 18 (18) 15 18 3 A 3 5 3 3 B 3 1 3 H O 8va 8va 7 V V V e V k V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V k Ie u [[[[[[[Full Full Full Full Full Full Full M M M M M M M 18 18 15 18 15 13 T 18 18 18 (18) 18 18 18 18 (18) A O O O O O B P H P sl. sl. V V V V V V V V V V 10 fV eV fV V V V eV fV V V V V V e l l j l j j l k d Ie V W V V V * Tremolo Bar Full 1 1/2 M * T 18 16 15 16 16 16 16 15 16 16 16 17 17 19 0 (0) A 15 14 15 15 15 15 14 15 15 B 1 sl. -

265 Edward M. Christian*

COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT ANALYSIS IN MUSIC: KATY PERRY A “DARK HORSE” CANDIDATE TO SPARK CHANGE? Edward M. Christian* ABSTRACT The music industry is at a crossroad. Initial copyright infringement judgments against artists like Katy Perry and Robin Thicke threaten millions of dollars in damages, with the songs at issue sharing only very basic musical similarities or sometimes no similarities at all other than the “feel” of the song. The Second Circuit’s “Lay Listener” test and the Ninth Circuit’s “Total Concept and Feel” test have emerged as the dominating analyses used to determine the similarity between songs, but each have their flaws. I present a new test—a test I call the “Holistic Sliding Scale” test—to better provide for commonsense solutions to these cases so that artists will more confidently be able to write songs stemming from their influences without fear of erroneous lawsuits, while simultaneously being able to ensure that their original works will be adequately protected from instances of true copying. * J.D. Candidate, Rutgers Law School, January 2021. I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John Kettle, for sparking my interest in intellectual property law and for his feedback and guidance while I wrote this Note, and my Senior Notes & Comments Editor, Ernesto Claeyssen, for his suggestions during the drafting process. I would also like to thank my parents and sister for their unending support in all of my endeavors, and my fiancée for her constant love, understanding, and encouragement while I juggled writing this Note, working full time, and attending night classes. 265 266 RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

Leon Russell – Primary Wave Music

ARTIST:TITLE:ALBUM:LABEL:CREDIT:YEAR:LeonThisCarneyTheW,P1972TightOutCarpentersAA&MWNow1973IfStopP1974LadyWill1975 SongI Were InRightO' Masquerade &AllBlueRussellRope The Thenfor Thata Stuff CarpenterYouWoodsWisp Jazz LEON RUSSELL facebook.com/LeonRussellMusic twitter.com/LeonRussell Imageyoutube.com/channel/UCb3- not found or type unknown mdatSwcnVkRAr3w9VBA leonrussell.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leon_Russell open.spotify.com/artist/6r1Xmz7YUD4z0VRUoGm8XN The ultimate rock & roll session man, Leon Russell’s long and storied career included collaborations with a virtual who’s who of music icons spanning from Jerry Lee Lewis to Phil Spector to the Rolling Stones. A similar eclecticism and scope also surfaced in his solo work, which couched his charmingly gravelly voice in a rustic yet rich swamp pop fusion of country, blues, and gospel. Born Claude Russell Bridges on April 2, 1942, in Lawton, Oklahoma, he began studying classical piano at age three, a decade later adopting the trumpet and forming his first band. At 14, Russell lied about his age to land a gig at a Tulsa nightclub, playing behind Ronnie Hawkins & the Hawks before touring in support of Jerry Lee Lewis. Two years later, he settled in Los Angeles, studying guitar under the legendary James Burton and appearing on sessions with Dorsey Burnette and Glen Campbell. As a member of Spector’s renowned studio group, Russell played on many of the finest pop singles of the ’60s, also arranging classics like Ike & Tina Turner’s monumental “River Deep, Mountain High”; other hits bearing his input include the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man,” Gary Lewis & the Playboys’ “This Diamond Ring,” and Herb Alpert’s “A Taste of Honey.” In 1967, Russell built his own recording studio, teaming with guitarist Marc Benno to record the acclaimed Look Inside the Asylum Choir LP. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Dear Secretary Salazar: I Strongly

Dear Secretary Salazar: I strongly oppose the Bush administration's illegal and illogical regulations under Section 4(d) and Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, which reduce protections to polar bears and create an exemption for greenhouse gas emissions. I request that you revoke these regulations immediately, within the 60-day window provided by Congress for their removal. The Endangered Species Act has a proven track record of success at reducing all threats to species, and it makes absolutely no sense, scientifically or legally, to exempt greenhouse gas emissions -- the number-one threat to the polar bear -- from this successful system. I urge you to take this critically important step in restoring scientific integrity at the Department of Interior by rescinding both of Bush's illegal regulations reducing protections to polar bears. Sarah Bergman, Tucson, AZ James Shannon, Fairfield Bay, AR Keri Dixon, Tucson, AZ Ben Blanding, Lynnwood, WA Bill Haskins, Sacramento, CA Sher Surratt, Middleburg Hts, OH Kassie Siegel, Joshua Tree, CA Sigrid Schraube, Schoeneck Susan Arnot, San Francisco, CA Stephanie Mitchell, Los Angeles, CA Sarah Taylor, NY, NY Simona Bixler, Apo Ae, AE Stephan Flint, Moscow, ID Steve Fardys, Los Angeles, CA Shelbi Kepler, Temecula, CA Kim Crawford, NJ Mary Trujillo, Alhambra, CA Diane Jarosy, Letchworth Garden City,Herts Shari Carpenter, Fallbrook, CA Sheila Kilpatrick, Virginia Beach, VA Kierã¡N Suckling, Tucson, AZ Steve Atkins, Bath Sharon Fleisher, Huntington Station, NY Hans Morgenstern, Miami, FL Shawn Alma, -

MCA-500 Reissue Series

MCA 500 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-500 Reissue Series: MCA 500 - Uncle Pen - Bill Monroe [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5348. Jenny Lynn/Methodist Preacher/Goin' Up Caney/Dead March/Lee Weddin Tune/Poor White Folks//Candy Gal/Texas Gallop/Old Grey Mare Came Tearing Out Of The Wilderness/Heel And Toe Polka/Kiss Me Waltz MCA 501 - Sincerely - Kitty Wells [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5350. Sincerely/All His Children/Bedtime Story/Reno Airport- Nashville Plane/A Bridge I Just Can't Burn/Love Is The Answer//My Hang Up Is You/Just For What I Am/It's Four In The Morning/Everybody's Reaching Out For Someone/J.J. Sneed MCA 502 - Bobby & Sonny - Osborne Brothers [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5356. Today I Started Loving You Again/Ballad Of Forty Dollars/Stand Beside Me, Behind Me/Wash My Face In The Morning/Windy City/Eight More Miles To Louisville//Fireball Mail/Knoxville Girl/I Wonder Why You Said Goodbye/Arkansas/Love's Gonna Live Here MCA 503 - Love Me - Jeannie Pruett [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5360. Love Me/Hold To My Unchanging Love/Call On Me/Lost Forever In Your Kiss/Darlin'/The Happiest Girl In The Whole U.S.A.//To Get To You/My Eyes Could Only See As Far As You/Stay On His Mind/I Forgot More Than You'll Ever Know (About Her)/Nothin' But The Love You Give Me MCA 504 - Where is the Love? - Lenny Dee [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5366. -

Festival 30000 LP SERIES 1961-1989

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS FESTIVAL 30,000 LP SERIES 1961-1989 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER AUGUST 2020 Festival 30,000 LP series FESTIVAL LP LABEL ABBREVIATIONS, 1961 TO 1973 AML, SAML, SML, SAM A&M SINL INFINITY SODL A&M - ODE SITFL INTERFUSION SASL A&M - SUSSEX SIVL INVICTUS SARL AMARET SIL ISLAND ML, SML AMPAR, ABC PARAMOUNT, KL KOMMOTION GRAND AWARD LL LEEDON SAT, SATAL ATA SLHL LEE HAZLEWOOD INTERNATIONAL AL, SAL ATLANTIC LYL, SLYL, SLY LIBERTY SAVL AVCO EMBASSY DL LINDA LEE SBNL BANNER SML, SMML METROMEDIA BCL, SBCL BARCLAY PL, SPL MONUMENT BBC BBC MRL MUSHROOM SBTL BLUE THUMB SPGL PAGE ONE BL BRUNSWICK PML, SPML PARAMOUNT CBYL, SCBYL CARNABY SPFL PENNY FARTHING SCHL CHART PJL, SPJL PROJECT 3 SCYL CHRYSALIS RGL REG GRUNDY MCL CLARION RL REX NDL, SNDL, SNC COMMAND JL, SJL SCEPTER SCUL COMMONWEALTH UNITED SKL STAX CML, CML, CMC CONCERT-DISC SBL STEADY CL, SCL CORAL NL, SNL SUN DDL, SDDL DAFFODIL QL, SQL SUNSHINE SDJL DJM EL, SEL SPIN ZL, SZL DOT TRL, STRL TOP RANK DML, SDML DU MONDE TAL, STAL TRANSATLANTIC SDRL DURIUM TL, STL 20TH CENTURY-FOX EL EMBER UAL, SUAL, SUL UNITED ARTISTS EC, SEC, EL, SEL EVEREST SVHL VIOLETS HOLIDAY SFYL FANTASY VL VOCALION DL, SDL FESTIVAL SVL VOGUE FC FESTIVAL APL VOX FL, SFL FESTIVAL WA WALLIS GNPL, SGNPL GNP CRESCENDO APC, WC, SWC WESTMINSTER HVL, SHVL HISPAVOX SWWL WHITE WHALE SHWL HOT WAX IRL, SIRL IMPERIAL IL IMPULSE 2 Festival 30,000 LP series FL 30,001 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 1 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS FL 30,002 THE BEST OF THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS, RECORD 2 TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS SFL 930,003 BRAZAN BRASS HENRY JEROME ORCHESTRA SEC 930,004 THE LITTLE TRAIN OF THE CAIPIRA LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SFL 930,005 CONCERTO FLAMENCO VINCENTE GOMEZ SFL 930,006 IRISH SING-ALONG BILL SHEPHERD SINGERS FL 30,007 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 1 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN FL 30,008 FACE TO FACE, RECORD 2 INTERVIEWS BY PETE MARTIN SCL 930,009 LIBERACE AT THE PALLADIUM LIBERACE RL 30,010 RENDEZVOUS WITH NOELINE BATLEY AUS NOELEEN BATLEY 6.61 30,011 30,012 RL 30,013 MORIAH COLLEGE JUNIOR CHOIR AUS ARR. -

Larry Gatlin Washington, DC’S Corey Spotlighting Individual Inductees Leading up to the Oct

September 3 2019, Issue 669 Pick Six: Label Draft 2019 Seven years ago, Country Aircheck’s Fantasy Label Draft began as an entertaining forum for radio pros to chat about artists and make bold predictions for the year to come. For the first six seasons, VP/GM Chuck Aly served as commissioner and declared winners based upon a method that is just questionable enough to have come from the New England Patriots’ camp, “Chuck’s Eyeball Test.” But this is 2019, and all bets are off. No participation trophies here! What good is a game without a winner? And how do you declare a winner without a score? As a new commissioner takes the field, a painstaking analysis was done to determine a fair- yet-competitive points system, which has been ratified by this year’s ownership group – KUPL/Portland’s MoJoe Roberts; KFRG/ Riverside, CA’s Heather Kind Of A Pig Deal: Premiere’s Bobby Bones, coach Chad Morris, Froglear; KRYS/Corpus Valory’s Justin Moore and singer/songwriter Joe Nichols (l-r) at MoJoe Roberts Kay Manley the Arkansas Razorbacks game Saturday (8/31). Christi, TX’s “Big Frank” Edwards; WGKX/Memphis’ Kay Manley; WMZQ/ NSHoF 2019: Larry Gatlin Washington, DC’s Corey Spotlighting individual inductees leading up to the Oct. Calhoun; and KWEN/Tulsa’s 14 Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame Gala continues with Jenny Law. But more on that songwriter/artist Larry Gatlin. Performing together as The Gatlin during post-game. Brothers for more than six decades, Larry, Steve Heather For his final call as the and Rudy are celebrating the 40th anniversary Corey -

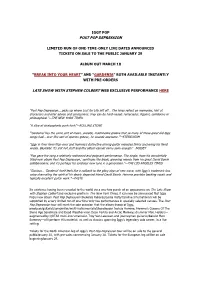

Post Pop Depression Late Show with Stephen Colbert

IGGY POP POST POP DEPRESSION LIMITED RUN OF ONE-TIME-ONLY LIVE DATES ANNOUNCED TICKETS ON SALE TO THE PUBLIC JANUARY 29 ALBUM OUT MARCH 18 “BREAK INTO YOUR HEART” AND “GARDENIA” BOTH AVAILABLE INSTANTLY WITH PRE-ORDERS LATE SHOW WITH STEPHEN COLBERT WEB EXCLUSIVE PERFORMANCE HERE “Post Pop Depression... picks up where Lust for Life left off… The lyrics reflect on memories, hint at characters and offer advice and confessions; they can be hard-nosed, remorseful, flippant, combative or philosophical.”—THE NEW YORK TIMES “A slice of stratospheric punk-funk”—ROLLING STONE “‘Gardenia’ has the same sort of mean, skeletal, machinelike groove that so many of those great old Iggy songs had… over this sort of spartan groove, he sounds awesome.”—STEREOGUM “Iggy in finer form than ever and Homme’s distinctive driving guitar melodies firmly anchoring his florid vocals. Basically: it’s shit hot stuff and this album cannot come soon enough”—NOISEY “Pop gave the song a relatively restrained and poignant performance. The single, from his wonderfully titled new album Post Pop Depression,’ continues the bleak, grooving moods from his great David Bowie collaborations, and it's perhaps his catchiest new tune in a generation.”—THE LOS ANGELES TIMES “Glorious… ’Gardenia’ itself feels like a callback to the glory days of new wave, with Iggy’s trademark low voice channeling the spirit of his dearly departed friend David Bowie. Homme provides backing vocals and typically excellent guitar work.”—PASTE Its existence having been revealed to the world via a one-two punch of an appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert and exclusive profile in The New York Times, it can now be announced that Iggy Pop’s new album Post Pop Depression (Rekords Rekords/Loma Vista/Caroline International) will be supported by a very limited run of one-time-only live performances in specially selected venues. -

Samantha Fish Homemade Jamz Jarekus Singleton

Buddy GDamnUYRight... JONNYLANG Q&A SAMANTHA FISH HOMEMADE JAMZ JAREKUS SINGLETON JOHNNY WINTER MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD Reissues Reviewed NUMBER THREE www.bluesmusicmagazine.com US $5.99 Canada $7.99 UK £4.60 Australia A$15.95 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © JOSH CHEUSE courtesy of RCA RECORDS NUMBER THREE 4 BUDDY GUY Best In Town by Robert Feuer 3 RIFFS & GROOVES From The Editor-In-Chief 8 TOM HAMBRIDGE Producing Buddy Guy 20 DELTA JOURNEYS “Catching Up” by Art Tipaldi 22 AROUND THE WORLD 10 SAMANTHA FISH “Blues Inspiration, Now And Tomorrow” Kansas City Bomber 24 Q&A with Jonny Lang by Vincent Abbate 26 BLUES ALIVE! 13 THE HOMEMADE JAMZ Lonnie Brooks 80th Birthday Bash BLUES BAND Harpin’ For Kid Ramos Benefit It’s A Family Affair 28 REVIEWS by Michael Cala New Releases Box Sets 17 JAREKUS SINGLETON Film Files Trading Hoops For The Blues 62 DOWN THE ROAD by Art Tipaldi 63 SAMPLER 3 64 IN THE NEWS TONY KUTTER © PHOTOGRAPHY PHOTOGRAPHY PHONE TOLL-FREE 866-702-7778 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB bluesmusicmagazine.com PUBLISHER: MojoWax Media, Inc. PRESIDENT: Jack Sullivan “As the sun goes down and the shadows fall, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Art Tipaldi on theWestside of Chicago, the blues has come to call.” CUSTOMER SERVICE: Kyle Morris GRAPHIC DESIGN: Andrew Miller Though the temperatures in Memphis during January’s 30th International Blues Challenge were in the 20s with wind chills cutting to below zero, the music on Beale CONTRIBUTING EDITORS David Barrett / Michael Cote / ?omas J. Cullen III Street was hotter then ever. Over 250 bands, solo/duo, and youth acts participated Bill Dahl / Hal Horowitz / Tom Hyslop in this exciting weeklong showcase of the blues in 20 Beale Street clubs.