A Popular Culture Study of Gender in Management Consulting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vita PDF Download

AMOR SCHUMACHER SYNCHRON (Rollen und Ensemble) Auswahl „The Dinner“ Splendid Nana Spier „Superstore“ BSG Frank Muth „Librarians“ Interopa Elke Weidemann „Billions“ Cinephon Reinhard Knapp „Patriots Day“ RC Bernhard Völger „Collateral Beauty“ FFS Marianne Gross „Christmas Office RC Kathrin Fröhlich Party“ „La La Land“ Cinephon Dr. Harald Wolff „House of Lies“ Cinephon Dr. Harald Wolff Wohnort: Berlin „Flikken Maastricht“ Antares Marc Böttcher Geburtsdatum: 14.08.1979 Sprachen: deutsch (Muttersprache), „Paradise“ Studio Funk Olaf Mierau spanisch (Muttersprache), „Homeland“ Cinephon Stephan Hoffmann englisch (fliessend), italienisch (GK) „Istanbul“ Taunusfilm Beate Klöckner Dialekte: hessisch, American English, „Better Call Saul“ BSG Frank Muth British English „Brigade“ SDI Uschi Hugo Akzente: englisch, spanisch, französisch, italienisch, arabisch „Bull“ Cinephon Stefan Ludwig Stimmlage: Alt „New Girl“ Cinephon Martin Schmitz „Bad Batch“ SDI Bernhard Völger Sprachberatung: Spanisch diverse Dialekte „Die irre Heldentour Interopa Christoph Cierpka des Billy Lynn“ „The Strain“ Cinephon Stefan Ludwig „Brotherhood“ Cinephon Wolfgang Ziffer AUSBILDUNG „Veep“ Cinephon Stefan Ludwig „Captain America: FFS Björn Schalla 2009, 2010, 2012 Larry Moss, Susan Civil War“ Batson Masterclass, „I Zombie“ Arena Synchron Gabrielle Pietermann Meisner Technique Mike Bernardin, Berlin „Relentless Justice“ Lautfabrik U.G. Benjamin Plath 2002 - 2006 Berliner Schule für „Longmire” FFS Marianne Gross Schauspiel „ScoobyDoo” SDI Sven Plate 2000 Method Studio London „Vampire -

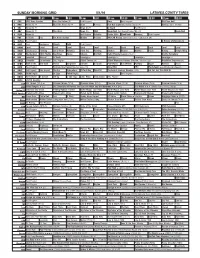

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Honoring the Dead of Both Sides

1A SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Like having Caribbean seeing SUNDAY EDITION a chef on signs of rebound in the shelf. 1C tourist industry. 1D Honoring the dead of both sides the Oaklawn Cemetery Memorial Ceremony Northern soldier for the Union, Johnny Reb Olustee weekend begins signaled the start of the 37th Olustee Battle for the Southern way of life — we honor them with memorial service at Festival Friday at 9 a.m. both this morning,” Montgomery said. Oaklawn Cemetery. After the presentation of the colors by the The Rev. James W. Binion, dressed as First Florida Honor Guard, former county Confederate President Jefferson Davis, was By DEREK GILLIAM commissioner James Montgomery led about guest speaker at the ceremony. Binion served [email protected] 60 spectators in the invocation. He spoke of in the Air Force with service in Southeast the North, the South and the fight that tore Asia during the Vietnam War. Confederate battle flags planted beside the nation apart. Binion said it was an honor to speak at JASON MATTHEW WALKER/Lake City Reporter the headstones of the 155 fallen soldiers “Remembering those who paid the ulti- David Dubi (left) and his brother, gently waved in a cold February breeze as mate price for a cause they believed in — the OAKLAWN continued on 5A John, retire the colors Friday. Horrors of war BLASTING AWAY brought home Civil War medical technology makes for gruesome display. By DEREK GILLIAM [email protected] Severed limbs lay scattered under the table with wounded soldiers bleeding nearby. -

With No Catchy Taglines Or Slogans, Showtime Has Muscled Its Way Into the Premium-Cable Elite

With no catchy taglines or slogans, Showtime has muscled its way into the premium-cable elite. “A brand needs to be much deeper than a slogan,” chairman David Nevins says. “It needs to be a marker of quality.” BY GRAHAM FLASHNER ixteen floors above the Wilshire corridor in entertainment. In comedy, they have a sub-brand of doing interesting things West Los Angeles, Showtime chairman and with damaged or self-destructive characters.” CEO David Nevins sits in a plush corner office Showtime can skew male (Ray Donovan, House of Lies) and female (The lined with mementos, including a prop knife Chi, SMILF). It’s dabbled in thrillers (Homeland), black comedies (Shameless), from the Dexter finale and ringside tickets to adult dramas (The Affair), docu-series (The Circus) and animation (Our the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight, which Showtime Cartoon President). It’s taken viewers on journeys into worlds TV rarely presented on PPV. “People look to us to be adventurous,” he explores, from hedge funds (Billions) to management consulting (House of says. “They look to us for the next new thing. Everything we Lies) and drug addiction (Patrick Melrose). make better be pushing the limits of the medium forward.” Fox 21 president Bert Salke calls Showtime “the thinking man’s network,” Every business has its longstanding rivalries. Coke and Pepsi. Marvel and noting, “They make smart television. HBO tries to be more things to more DC. For its first thirty-odd years, Showtime Networks (now owned by CBS people: comedy specials, more half-hours. Showtime is a bit more interested Corporation) ran a distant second to HBO. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Report by % of Episodes Directed by Women

2013 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by % of EPISODES DIRECTED BY WOMEN) Title Total # of # Episodes Female # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Signatory Company Network Episodes Directed by % Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Females Male % Male % Female % Female % Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A.N.T. Farm 39 0 0% 30 77% 9 23% 0 0% 0 0% It's a Laugh Productions, Inc. Disney Channel After Lately 8 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% CP Entertainment Services, LLC E! American Horror Story 13 0 0% 10 77% 3 23% 0 0% 0 0% Twentieth Century Fox Television FX Anger Management 54 0 0% 53 98% 1 2% 0 0% 0 0% Anger Productions, Inc. FX Californication 12 0 0% 11 92% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% Showtime Pictures Development Showtime Company Crash and Bernstein 26 0 0% 24 92% 2 8% 0 0% 0 0% It's a Laugh Productions, Inc. Disney XD Defiance 11 0 0% 9 82% 2 18% 0 0% 0 0% Open 4 Business Productions LLC Syfy Dog with a Blog 21 0 0% 20 95% 1 5% 0 0% 0 0% It's a Laugh Productions, Inc. Disney Channel Exes, The 12 0 0% 12 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% King Street Productions Inc. TV Land Falling Skies 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Turner North Center Productions, Inc. TNT Fringe 13 0 0% 12 92% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% Warner Bros. -

There Goes 'The Neighborhood'

NEED A TRIM? AJW Landscaping 910-271-3777 September 29 - October 5, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching Licensed – Insured – FREE Estimates 00941084 The cast of “The Neighborhood” Carry Out WEEKDAYMANAGEr’s SPESPECIALCIAL $ 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Pizzas5 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5and 16EACH oz. Beverage (AdditionalMonday toppings $1.40Thru each) Friday There goes ‘The from 11am - 4pm Neighborhood’ 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, September 29, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Comedy with a purpose: It’s a beautiful day in ‘The Neighborhood’ By Kyla Brewer munity. Calvin’s young son, Marty The cast shuffling meant the pi- TV Media (Marcel Spears, “The Mayor”), is lot had to be reshot, and luckily the happy to see Dave, his wife, Gem- cast and crew had an industry vet- t the end of the day, it’s nice to ma (Beth Behrs, “2 Broke Girls”), eran at the helm. Legendary televi- Akick back and enjoy a few and their young son, Grover (Hank sion director James Burrows, best laughs. Watching a TV comedy is a Greenspan, “13 Reasons Why”). known for co-creating the TV classic great way to unwind, but some sit- Meanwhile, Calvin’s older unem- “Cheers,” directed both pilots for coms are more than just a string of ployed son, Malcolm (Sheaun McK- “The Neighborhood.” A Hollywood snappy one-liners. A new series inney, “Great News”), finds it enter- icon, he’s directed more than 50 takes a humorous look at a serious taining to watch his frustrated fa- television pilots, and he reached a issue as it tackles racism in America. -

Nucoda Stars in KMP Television Pipeline From

Nucoda Stars in KMP Television Pipeline From www.imagesystems.tv Keep Me Posted (a FotoKem Company) is a post production facility specializing in the finishing of television, commercials, promos, trailers, and feature productions. For over a decade, the team at KMP has successfully delivered thousands of hours of programming to every major network and cable outlet for an enviable list of drama, comedy and reality shows. In designing a workflow that would be successful for the facility while responding to the needs of their creative customers, KMP chose Nucoda Film Master, crowning the facility with the biggest throughput on Image System’s DI color grading and finishing solution. In today’s dynamic media environment, facilities face a challenging production landscape with a changing and technically diverse range of deliverables. Good facilities respond to these changes, but great facilities strategically develop workflows that answer the demands facing their customers. Regardless of origination format – film or digital – KMP works closely with production, post and editorial early in the process to ensure success from dailies onward. After careful investigation of systems that could support their vision, KMP chose Nucoda Film Master. Claire Danes as Carrie Mathison in Homeland (Photo: Ronen Akerman/SHOWTIME) Integrating Nucoda Film Master into the and color grading experiences, and we owe a big piece of that KMP Workflow success to the Nucoda.” Early in 2010, KMP purchased the first Nucoda Film Master “We have built a flexible, file-based, customer-centric, technical to integrate and power KMP’s television pipeline. Within a few powerhouse,” notes Andrew Hanges, senior VP/GM and co- months, as work increased and powerful applications of the founder of KMP. -

Wednesday Morning, March 28

WEDNESDAY MORNING, MARCH 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View 50 Cent; Vera Wang; Live! With Kelly Jessica Biel; Abi- 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Bone Hampton. (cc) (TV14) gail Breslin. (N) (cc) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today The Hiring Our Heroes Today initiative. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Gina teaches Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Marco about Spanish. (cc) (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent An ear 12/KPTV 12 12 surgeon’s murder. (TV14) International Fel- Paid Paid Paid Zula Patrol (cc) Pearlie (TVY7) Through the Bible International Fel- Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 lowship (TVY) lowship Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Winning With 360 Degree Life Pro-Claim Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) Wisdom (cc) Scenes (cc) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TVPG) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (cc) Divorce Court (N) Excused (cc) Excused (cc) Cheaters (cc) Cheaters (cc) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (TVG) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) (TV14) (TV14) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Hunter (cc) (TVPG) Dog the Bounty Hunter (cc) (TVPG) Criminal Minds Mayhem. -

Actor Alicia Witt Turns Musician with 'Revisionary History'

ALICIA WITT Alicia Witt has had an over three-decade long career, starting with her acting debut as Alia in David Lynch's classic ‘Dune’. Alicia received rave reviews for her role as Paula in Season 6 of AMC’s critically acclaimed series The Walking Dead. Witt also appeared during Season 4 of ABC’s ‘Nashville’ as country star Autumn Chase and in the new Twin Peaks on Showtime, reprising her role as Gerstein Hayward. Witt most recently was seen haunting John Cho’s character as Demon Nikki on Season 2 of Fox’s The Exorcist; other recent credits include the Emmy-award winning Showtime series ‘House of Lies’ opposite Don Cheadle and the hit WB series ‘Supernatural’. Witt is also well known to Hallmark audiences for her annual Christmas movies; her latest, which she co-wrote and is producing, will be released later this year. She can also be seen this fall as Marjorie Cameron in Season 2 of anthology series Lore, on Amazon. In 2014, Alicia joined the 5th Season of Emmy-award winning FX series ‘Justified’ with Timothy Olyphant. Alicia played Wendy Crowe, the smart and sexy paralegal sister of crime lord Daryl Crowe (Michael Rapaport) who takes matters into her own hands to bring him to justice in the Season 5 finale. On stage, she most recently appeared at the Geffen Playhouse in the Los Angeles debut of Tony-nominated Neil Labute play ‘reasons to be pretty’. In 2013, Alicia appeared opposite Peter Bogdanovich and Cheryl Hines in the independent family dramedy 'Cold Turkey', in a performance which NY Daily News critic David Edelstein hailed as one of the best of 2013. -

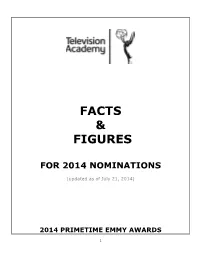

95 Updated Facts/Trivia Copy

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2014 NOMINATIONS (updated as of July 21, 2014) 2014 PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS 1 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2013 Behind The Candelabra – 11 Boardwalk Empire – 5 66th Annual Tony Awards – 4 Saturday Night Live – 4 The Big Bang Theory - 3 Breaking Bad – 3 Disney Mickey Mouse Croissant de Triomphe – 3 House of Cards -3 Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence In The House of God - 3 30 Rock - 2 The 55th Annual Grammy Awards – 2 American Horror Story: Asylum- 2 American Masters – 2 Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown – 2 The Colbert Report – 2 Da Vinci’s Demons – 2 Deadliest Catch – 2 Game of Thrones - 2 Homeland – 2 How I Met Your Mother - 2 The Kennedy Center Honors - 2 The Men Who Built America - 2 Modern Family – 2 Nurse Jackie – 2 Veep – 2 The Voice - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2013 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Modern Family Drama Series: Breaking Bad Miniseries or Movie: Behind The Candelabra Reality-Competition Program: The Voice Variety, Music or Comedy Series: The Colbert Report PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Julia Louis-Dreyfus (Veep) Lead Actor: Jim Parsons (The Big Bang Theory) Supporting Actress: Merritt Wever (Nurse Jackie) Supporting Actor: Tony Hale (Veep) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Claire Danes (Homeland) Lead Actor: Jeff Daniels (The Newsroom) Supporting Actress: Anna Gunn (Breaking Bad) Supporting Actor: Bobby Cannavale (Boardwalk Empire) Miniseries/Movie: Lead Actress: Laura Linney (The Big C: Hereafter) Lead Actor: Michael Douglas (Behind The Candelabra) Supporting Actress: Ellen Burstyn (Political Animals) Supporting -

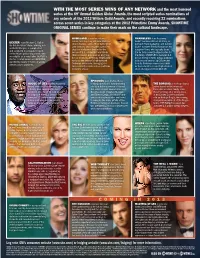

WITH the MOST SERIES WINS of ANY NETWORK and the Most

WITH THE MOST SERIES WINS OF ANY NETWORK and the most honored series at the 69th Annual Golden Globe® Awards, the most scripted series nominations of any network at the 2012 Writers Guild Awards, and recently receiving 22 nominations across seven series in key categories at the 2012 Primetime Emmy® Awards, SHOWTIME ORIGINAL SERIES continue to make their mark on the cultural landscape. HOMELAND, a one-hour drama SHAMELESS stars Academy ® DEXTER® stars Michael C. Hall in series, tells the story of Carrie Mathison Award nominee William H. Macy, as ® (Claire Danes), a CIA officer battling her patriarch Frank Gallagher, and Golden his Golden Globe Award-winning role ® as Dexter Morgan, a complicated own demons, who becomes convinced Globe nominee Emmy Rossum as his and conflicted blood-spatter expert that the intelligence that led to the daughter Fiona, who typically bears for the Miami police department who rescue of U.S. soldier Nicholas Brody the de facto parent badge/burden for ® (Damian Lewis) was a set-up and may the family. SHAMELESS averaged 4.8 moonlights as a serial killer. DEXTER is be connected to Al Qaeda. HOMELAND million weekly viewers across platforms the No. 1 rated series on SHOWTIME, ranks as the network’s highest-rated in its second season, up 27 percent watched by nearly 5.5 million weekly freshman series ever, averaging 4.4 from its freshman season and ranks viewers across platforms. million weekly viewers across platforms as the network’s second highest-rated in its first season. show, sitting just behind DEXTER®. EPISODES stars Matt LeBlanc HOUSE OF LIES starring Academy in his Golden Globe® Award-winning THE BORGIAS a one-hour drama Award® nominee Don Cheadle, is role as a fictional version of himself.