The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute: a Case Study in Library, Archives, and Museum Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Position Overview

DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Birmingham, AL Search conducted by Development Resources, inc. www.driconsulting.com Art Free For All The Birmingham Museum of Art (BMA) sparks the creativity, imagination, and liveliness of Birmingham by connecting all its citizens to the experience, meaning, and joy of art. Founded in 1951, the Birmingham Museum of Art has one of the finest collections in the Southeast supported by a strong educational program designed to make the arts come alive for children and adults throughout the region. More than 27,000 objects represent a rich panorama of cultures, including Asian, European, American, African, Pre-Columbian, and Native American. Highlights include the Museum’s collection of Asian art, considered the finest and most comprehensive in the Southeast; a remarkable Kress collection of Renaissance and Baroque paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts from the late 13th century to the 1750s; and the Museum’s world-renowned collection of Wedgwood, the largest outside of England. The Museum connects with the community through educational programs and curated exhibitions that engage, entertain, and enlighten visitors. Programs are designed around the Museum’s permanent collection and changing exhibitions, and provide opportunities for all ages and levels of experience to connect with art. In its most recent fiscal year, BMA welcomed 124,039 visitors, an increase of 3,000 guests over the previous year. This increase was spurred by relevant and innovative exhibitions and programs, such as the popular Family Festivals and the Barbie: Dreaming of a Female Future exhibition, which received widespread acclaim from visitors and the media. Barbie: Dreaming of a Female Future Emblematic of the types of programs and exhibitions the Museum features, this exhibition takes a critical look at Barbie on her 60th anniversary. -

Travel Professionals | Greater Birmingham Convention & Visitors Bureau – Birmingham, AL

CONTACT MENU ATTRACTIONS SHOPPING DINING OUTDOORS NIGHTLIFE Plan a Tour When tour groups get down to Birmingham, they get down to the business of exploring the city’s personality. Among the themed tours are trips to sample the city’s locally-produced snacks, real Southern dining and the influence of immigrants on the city’s cuisine. Other tours explore the diversity of Birmingham’s ethnic communities, reflected in the architecture and cultural events throughout the city. Plan a tour to visit the Eternal Word Television Network, founded by Mother Mary Angelica. Take in the historic sites from Birmingham’s tumultuous role in America’s Civil Rights Movement. Hear interesting tales from the city’s rowdy pioneer days. Visit the factory where the popular M-Class Mercedes-Benz is manufactured. And sample the art, outdoors, dining, sports and entertainment that bring tour groups back to Birmingham time and again. (Sample itineraries include more locations than a full day of touring will accommodate. Let us help you customize your tour from these suggested destinations. Reservations are required and appreciated.) Itineraries Grits, Greens and Greeks: The Southern Foods Tour Spend a day sampling the flavors of Birmingham. Wake up the day with breakfast at Niki’s West, a Birmingham institution, where they serve up a heaping helping of Southern favorites: country ham, cheese grits, cathead biscuits with sawmill gravy, and eggs any way you like ‘em. Then walk off some of that fine meal at the Pepper Place Saturday Market. This seasonal spread of Southern foods is a delight to wander through. Farmers’ stalls are filled with peaches, peppers and tomatoes. -

Exhibition Calendar 2019–20

EXHIBITION CALENDAR 2019–20 Rachel Eggers Manager of Public Relations [email protected] 206.654.3151 The following information is subject to change. Prior to publication, please confirm dates, titles, and other information with the Seattle Art Museum public relations office. 2 SEATTLE ART MUSEUM – NOW ON VIEW Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement Seattle Art Museum June 13–September 8, 2019 As industrialization brought sweeping and dehumanizing changes to 19th- century England, a small group of artists reasserted the value of the handmade. Calling themselves the Pre-Raphaelites, they turned to the unlikely model of medieval European craftsmen as a way of moving forward. Victorian Radicals presents an unprecedented 145 paintings, drawings, books, sculpture, textiles, and decorative arts—many never before exhibited outside of the UK—by the major artists associated with this rebellious brotherhood. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Edward Burne-Jones, and William Morris dubbed themselves the Pre-Raphaelites in reaction to the Royal Academy of Arts, whose methods to artmaking they regarded to be as formulaic as industrial methods of production. This movement had broad implications and inspired a wide range of industries to rebel against sterility and strive to connect art to everyday life. The Pre-Raphaelites and members of the later Arts & Crafts movement operated from a moral commitment to honest labor, the handmade object, and the ability of art to heal a society dehumanized by industry and mechanization. The works of the men and women presented in the exhibition illustrate a spectrum of avant-garde practices of the Victorian period and demonstrate Britain’s first modern art response to industrialization. -

Hank Willis Thomas

Goodman Gallery Hank Willis Thomas Biography Hank Willis Thomas (b. 1976, New Jersey, United States) is a conceptual artist working primarily with themes related to perspective, identity, commodity, media, and popular culture. Thomas has exhibited throughout the United States and abroad including the International Center of Photography, New York; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain; Musée du quai Branly, Paris; Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong, and the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Netherlands. Thomas’ work is included in numerous public collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum, New York; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. His collaborative projects include Question Bridge: Black Males, In Search Of The Truth (The Truth Booth), Writing on the Wall, and the artist-run initiative for art and civic engagement For Freedoms, which in 2017 was awarded the ICP Infinity Award for New Media and Online Platform. Thomas is also the recipient of the Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship (2019), the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship (2018), Art for Justice Grant (2018), AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize (2017), Soros Equality Fellowship (2017), and is a member of the New York City Public Design Commission. Thomas holds a B.F.A. from New York University (1998) and an M.A./M.F.A. from the California College of the Arts (2004). In 2017, he received honorary doctorates from the Maryland Institute of Art and the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts. Artist Statement Hank Willis Thomas is an American visual photographer whose primary interested are in race, advertising and popular culture. -

Final Report of a Study of IMLS Youth Programs, 1998-2003

Museums and Libraries Engaging America’s Youth: Final Report of a Study of IMLS Youth Programs, 1998-2003 Institute of Museum and Library Services 1800 M St. NW, 9th floor Washington, DC 20036 202-653-IMLS (4657) www.imls.gov IMLS TTY (for hearing-impaired individuals) 202-563-4699 IMLS will provide visually impaired or learning disabled individuals with an audio recording of this publication upon request. Printed December 2007 Prepared by Judy Koke, Project Director Lynn Dierking, Ph.D., Senior Researcher Institute for Learning Innovation Edgewater, MD Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Information not available at the time of publication. Table of Contents Dear Colleague.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 8 Background............................................................................................................................................... 8 Key Findings.............................................................................................................................................. 8 General Recommendations ...................................................................................................................10 -

Reciprocal Museum List

RECIPROCAL MUSEUM LIST DIA members at the Affiliate level and above receive reciprocal member benefits at more than 1,000 museums and cultural institutions in the U.S. and throughout North America, including free admission and member discounts. This list includes organizations affiliated with NARM (North American Reciprocal Museum) and ROAM (Reciprocal Organization of American Museums). Please note, some museums may restrict benefits. Please contact the institution for more information prior to your visit to avoid any confusion. UPDATED: 10/28/2020 DIA Reciprocal Museums updated 10/28/2020 State City Museum AK Anchorage Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center AK Haines Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center AK Homer Pratt Museum AK Kodiak Kodiak Historical Society & Baranov Museum AK Palmer Palmer Museum of History and Art AK Valdez Valdez Museum & Historical Archive AL Auburn Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art AL Birmingham Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA), UAB AL Birmingham Birmingham Civil Rights Institute AL Birmingham Birmingham Museum of Art AL Birmingham Vulcan Park and Museum AL Decatur Carnegie Visual Arts Center AL Huntsville The Huntsville Museum of Art AL Mobile Alabama Contemporary Art Center AL Mobile Mobile Museum of Art AL Montgomery Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts AL Northport Kentuck Museum AL Talladega Jemison Carnegie Heritage Hall Museum and Arts Center AR Bentonville Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art AR El Dorado South Arkansas Arts Center AR Fort Smith Fort Smith Regional Art Museum AR Little Rock -

Executive Director Alabama Humanities Foundation Birmingham, AL

LEADERSHIP PROFILE Executive Director Alabama Humanities Foundation Birmingham, AL Fostering learning, understanding, and appreciation of Alabama’s people, communities and cultures. THE OPPORTUNITY The Alabama Humanities Foundation has been a committed leader in supporting and promoting the humanities in Alabama since 1974. Driven by the idea that knowledge of the humanities provides the ability to reason, question and to think creatively and critically, AHF champions programs that materially strengthen the community and more deeply engage its citizens. Through the celebration and study of literature, history, law, philosophy, and the arts, the foundation helps to enrich Alabama and promote its many cultural assets. Given the challenges that surround civic dialogue in America at present, AHF can play a key role in Alabama Humanities Foundation Executive Director Leadership Profile August 2020 Page 2 of 7 celebrating how humanities make us better, serving to bring people together and build stronger communities. AHF is at a critical inflection point. The new Executive Director will leverage leadership, creativity, cultural competence, and deep-seated passion for the humanities to help realize AHF’s vision for the future. S/he will embrace change and organizational imperatives that include charting the course for the next chapter of the foundation’s work, advancing organizational clarity and consensus among the board and staff, and raising the organization’s profile, relevance, and impact throughout Alabama and beyond. The opportunity for the Executive Director is bold and compelling: to advance the foundation as a vital part of Alabama’s cultural fabric, thereby strengthening the state through captivating programs and support of important initiatives in the humanities. -

Samford University School of the Arts Division of Music Assistant/Associate Professor of Music and Worship (9-Month, Tenure-Track)

Samford University School of the Arts Division of Music Assistant/Associate Professor of Music and Worship (9-month, Tenure-Track) Samford University’s Division of Music invites applicants interested in serving in a Christian university environment to apply for the position of Assistant/Associate Professor of Music and Worship (9-month, Tenure-Track) to begin August 2021. Qualifications Qualified candidates will have earned a master’s degree in music or related field from an institutionally accredited university and gained exceptional professional experience in the field. A terminal degree in the discipline and robust experience in vocational worship ministry is preferred. Demonstrated experience as a worship leader and church musician of an array of musical styles, ministry administration and programming, and pastoral leadership in the local church is required. Responsibilities The successful candidate will demonstrate potential for recruiting, training, and retaining undergraduate and graduate students for worship leadership, music and worship, and church music programs. Responsibilities include leading worship-related music ensembles, recruiting and mentoring students, guiding program and curricula development, collaborating with Samford’s Center for Worship and the Arts, and teaching courses in the area of church music and worship leadership. The candidate will focus on growing a program that integrates both current practice and theory in worship leadership. Additional responsibilities may include, but are not limited to, the following areas based on candidate strengths and university need: ensemble directing and coaching; worship technology, commercial music, and live sound design; songwriting; recording arts management; applied performance instruction; pastoral leadership and practice; or other work in the creative and worship arts. -

The Birmingham District Story

I THE BIRMINGHAM DISTRICT STORY: A STUDY OF ALTERNATIVES FOR AN INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE DISTRICT A Study Prepared for the National Park Service Department of the Interior under Cooperative Agreement CA-5000·1·9011 Birmingham Historical Society Birmingham, Alabama February 17, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT IS THE BIRMINGHAM HERITAGE DISTRICT? Tab 1 Preface National Park Service Project Summary The Heritage District Concept Vision, Mission, Objectives A COLLECTION OF SITES The Birmingham District Story - Words, Pictures & Maps Tab 2 Natural and Recreational Resources - A Summary & Maps Tab 3 Cultural Resources - A Summary, Lists & Maps Tab 4 Major Visitor Destinations & Development Opportunities A PARTNERSHIP OF COMMITTED INDIVIDUALS & ORGANIZATIONS Tabs Statements of Significance and Support Birmingham District Steering & Advisory Committees Birmingham District Research & Planning Team Financial Commitment to Industrial Heritage Preservation ALTERNATIVES FOR DISTRICT ORGANIZATION Tab 6 Issues for Organizing the District Alternatives for District Organization CONCLUSIONS, EARLY ACTION, COST ESTIMATES, SITE SPECIFIC Tab 7 DEVELOPMENTS, ECONOMIC IMPACT OF A HERITAGE DISTRICT APPENDICES Tab 8 Study Process, Background, and Public Participation Recent Developments in Heritage Area and Greenway Planning The Economic Impact of Heritage Tourism Visitor Center Site Selection Analysis Proposed Cultural Resource Studies Issues and Opportunities for Organizing the Birmingham Industrial Heritage District Index r 3 PREFACE This study is an unprecedented exploration of this metropolitan area founded on geology, organized along industrial transportation systems, developed with New South enthusiasm and layered with physical and cultural strata particular to time and place. It views as whole a sprawling territory usually described as fragmented. It traces historical sequence and connections only just beginning to be understood. -

Birmingham-Travel-Planners-Guide.Pdf

TRAVEL PLANNERS GUIDE *Cover Image: The Lyric Theatre was built in 1914 as a venue for performances by national vaudeville acts. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Lyric 2has | beenTRAVEL restored andPLANNERS is part of Birmingham’s GUIDE historic theater district which also includes the Alabama Theatre, a 1920s movie palace. TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME 07 WHAT TO DO 09 WHERE TO STAY 29 WHERE TO EAT (BY LOCATION) 53 BESSEMER/WEST 54 DOWNTOWN/SOUTHSIDE 54 EASTWOOD/IRONDALE/LEEDS 55 HOMEWOOD/MOUNTAIN BROOK/INVERNESS 55 HOOVER/VESTAVIA HILLS 55 BIRMINGHAM AREA INFORMATION 57 TRAVEL PLANNERS GUIDE | 3 GREATER BIRMINGHAM HOTELS 4 | TRAVEL PLANNERS GUIDE NORTH BIRMINGHAM DOWNTOWN BIRMINGHAM EAST BIRMINGHAM SOUTH BIRMINGHAM Best Western Plus Anchor Motel (45) American Interstate Motel (49) America’s Best Value Inn - Gardendale (1) Homewood/Birmingham (110) Apex Motel (31) America’s Best Inns Birmingham Comfort Suites Fultondale (5) Airport Hotel (46) America’s Best Value Inn & Suites - Cobb Lane Bed and Breakfast (43) Homewood/Birmingham (94) Days Inn Fultondale (8) America’s Best Inn Birmingham East (54) Courtyard by Marriott Birmingham Baymont Inn & Suites Fairfield Inn & Suites Birmingham Downtown/West (28) Americas Best Value Inn - Birmingham/Vestavia (114) Fultondale/I-65 (6) East/Irondale (65) Days Inn Birmingham/West (44) Best Western Carlton Suites Hotel (103) Hampton Inn America’s Best Value Inn - Leeds (72) Birmingham - Fultondale (4) DoubleTree by Hilton Birmingham (38) Candlewood Suites Birmingham/ Anchor Motel -

PETER PINCUS (B

PETER PINCUS (b. 1982 Rochester, NY) EDUCATION 2011 M.F.A. New York State College of Ceramics, Alfred University, Alfred, NY 2005 B.F.A. New York State College of Ceramics, Alfred University, Alfred, NY SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Peter Pincus: Art in the Age of Influence, Ferrin Contemporary, North Adams, MA 2019 Peter Pincus. Duane Reed Gallery, St. Louis, MO Peter Pincus: Chroma, American Museum of Ceramics Art, Pomona, CA 2018 Peter Pincus: Channeling Josiah Wedgwood, Ferrin Contemporary, North Adams, MA Peter Pincus: Color and Form, Baum Gallery, Conway, AR 2017 Hall of Mirrors, Sherry Leedy Contemporary, Kansas City, MO 2015 Morean Art Center, St. Petersberg, FL Chocolate, AKAR Gallery, Iowa City, IA Accomplice, Plinth Gallery, Denver CO Sleep, in Spite of the Storm, Main Street Arts, Clifton Springs, NY 2013 Solo Exhibition, Spencer Hill Gallery, Corning, NY Studio KotoKoto, Studiokotokoto.com 2012 Where You Go, I Go., Coach Street Clay, Canandaigua, NY SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2019 The Diana Reitberger Collection, Gardiner Museum, Toronto, Canada All That’s Gold Does Glitter, Sans Casino, Macao, China On Differentiation and Affinity, Pewabic, Detroit, MI Old Church Pottery Show, The Art School at Old Church, Demarest, NJ 2018 ArtAspen – Duane Reed Gallery, Aspen, CO ART SHINAN 2018 International Ceramic Exhibition, Qingdao Art Museum, Qingdao, China Vasa Vasorum, Peter Projects, Santa Fe, NM Crazy Beautiful, Kenise Barnes Fine Art, Larchmont, NY Form to Function II, The Delaware Contemporary, Wilmington, DE New York Ceramics and Glass -

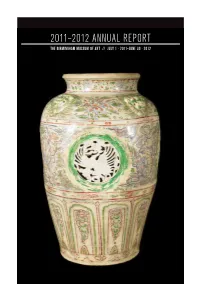

2011–2012 Annual Report

2011–2012 ANNUAL REPORT THE BIRMINGHAM MUSEUM OF ART // JULY 1 · 2011–JUNE 30 · 2012 2011–2012 ANNUAL REPORT THE BIRMINGHAM MUSEUM OF ART // JULY 1 · 2011–JUNE 30 · 2012 CONTENTS THE YEAR IN REVIEW 5 EXHIBITIONS 9 Ralph D. Cook – Chairman of the Board EDUCATION AND PUBLIC PROGRAMS 17 Gail C. Andrews – The R. Hugh Daniel Director EVENTS 25 Editor – Rebecca Dobrinski Design – James Williams SUPPORT GROUPS 31 Photographer – Sean Pathasema STAFF 36 MISSION To provide an unparalleled cultural and educational experience to a diverse community by collecting, presenting, interpreting, and preserving works of art of the highest quality. FINANCIAL REPORT 39 Birmingham Museum of Art ACQUISITIONS 43 2000 Rev. Abraham Woods Jr. Blvd. Birmingham, AL 35203 COLLECTION LOANS 52 Phone: 205.254.2565 www.artsbma.org BOARD OF TRUSTEES 54 [COVER] Jar, 16th century, Collection of the Art Fund, Inc. at the Birmingham Museum of Art; Purchase with funds provided by the Estate of William M. Spencer III AFI289.2010 MEMBERSHIP AND SUPPORT 57 THE YEAR IN REVIEW t is a pleasure to share highlights from our immeasurably by the remarkable bequest of I 2011–12 fiscal year. First, we are delighted long-time trustee, William M. Spencer III. Our to announce that the Museum’s overall collection, along with those at the MFA Boston attendance last year jumped by an astonishing and Metropolitan Museum of Art, is ranked as 24 percent. While attendance is only one metric one of the top three collections of Vietnamese by which we gauge interest and enthusiasm Ceramics in North America. The show and for our programs, it is extremely validating catalogue, published by the University of as we continue to grow and explore new ways Washington Press, received generous national to engage our audience.