Calculus Challenge #14 Calculus at the Battle of Trafalgar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9781501756030 Revised Cover 3.30.21.Pdf

, , Edited by Christine D. Worobec For a list of books in the series, visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. From Victory to Peace Russian Diplomacy aer Napoleon • Elise Kimerling Wirtschaer Copyright © by Cornell University e text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives . International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/./. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, East State Street, Ithaca, New York . Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Wirtschaer, Elise Kimerling, author. Title: From victory to peace: Russian diplomacy aer Napoleon / by Elise Kimerling Wirtschaer. Description: Ithaca [New York]: Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, . | Series: NIU series in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian studies | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identiers: LCCN (print) | LCCN (ebook) | ISBN (paperback) | ISBN (pdf) | ISBN (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Russia—Foreign relations—–. | Russia—History— Alexander I, –. | Europe—Foreign relations—–. | Russia—Foreign relations—Europe. | Europe—Foreign relations—Russia. Classication: LCC DK.W (print) | LCC DK (ebook) | DDC ./—dc LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ Cover image adapted by Valerie Wirtschaer. is book is published as part of the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot. With the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Pilot uses cutting-edge publishing technology to produce open access digital editions of high-quality, peer-reviewed monographs from leading university presses. -

The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte's Invasion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London imesT Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia Julia Dittrich East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dittrich, Julia, "“We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1457. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia _______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Julia Dittrich August 2012 _______________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Napoleon Bonaparte, The London Times, English Identity ABSTRACT “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia by Julia Dittrich “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia aims to illustrate how The London Times interpreted and reported on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. -

Austerlitz, Napoleon and the Destruction of the Third Coalition

H-France Review Volume 7 (2007) Page 67 H-France Review Vol. 7 (February 2007), No. 16 Robert Goetz, 1805: Austerlitz, Napoleon and the Destruction of the Third Coalition. Greenhill: London, 2005. 368 pp. Appendices, Maps, Tables, Illustrations and Index. ISBN 1-85367644-6. Reviewed by Frederick C. Schneid, High Point University. Operational and tactical military history is not terribly fashionable among academics, despite its popularity with general readers. Even the “new military history” tends to shun the traditional approach. Yet, there is great utility and significance to studying campaigns and battles as the late Russell Weigley, Professor of History at Temple University often said, “armies are for fighting.” Warfare reflects the societies waging it, and armies are in turn, reflections of their societies. Robert Goetz, an independent historian, has produced a comprehensive account of Austerlitz, emphasizing Austrian and Russian perspectives on the event. “The story of the 1805 campaign and the stunning battle of Austerlitz,” writes Goetz, “is the story of the beginning of the Napoleon of history and the Grande Armée of legend.”[1] Goetz further stresses, “[n]o other single battle save Waterloo would match the broad impact of Austerlitz on the course of European history.”[2] Certainly, one can take exception to these broad sweeping statements but, in short, they properly characterize the established perception of the battle and its impact. For Goetz, Austerlitz takes center stage, and the diplomatic and strategic environment exists only to provide context for the climactic encounter between Napoleon and the Russo-Austrian armies. Austerlitz was Napoleon’s most decisive victory and as such has been the focus of numerous military histories of the Napoleonic Era. -

Wellingtons Peninsular War Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WELLINGTONS PENINSULAR WAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Julian Paget | 288 pages | 01 Jan 2006 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9781844152902 | English | Barnsley, United Kingdom Wellingtons Peninsular War PDF Book In spite of the reverse suffered at Corunna, the British government undertakes a new campaign in Portugal. Review: France '40 Gold 16 Jan 4. Reding was killed and his army lost 3, men for French losses of 1, Napoleon now had all the pretext that he needed, while his force, the First Corps of Observation of the Gironde with divisional general Jean-Andoche Junot in command, was prepared to march on Lisbon. VI, p. At the last moment Sir John had to turn at bay at Corunna, where Soult was decisively beaten off, and the embarkation was effected. In all, the episode remains as the bloodiest event in Spain's modern history, doubling in relative terms the Spanish Civil War ; it is open to debate among historians whether a transition from absolutism to liberalism in Spain at that moment would have been possible in the absence of war. On 5 May, Suchet besieged the vital city of Tarragona , which functioned as a port, a fortress, and a resource base that sustained the Spanish field forces in Catalonia. The move was entirely successful. Corunna While the French were victorious in battle, they were eventually defeated, as their communications and supplies were severely tested and their units were frequently isolated, harassed or overwhelmed by partisans fighting an intense guerrilla war of raids and ambushes. Further information: Lines of Torres Vedras. The war on the peninsula lasted until the Sixth Coalition defeated Napoleon in , and it is regarded as one of the first wars of national liberation and is significant for the emergence of large-scale guerrilla warfare. -

Process Dynamics 1 Battle of Trafalgar (1805)

2015 Practice 1 Process dynamics Process Dynamics (W.L. Luyben) Approximate description of the battle with a continuous process. Simulate the processes A, B, C, answer the questions, provide graphs. 1 Battle of Trafalgar (1805) 32 ships led by Admiral Lord Nelson against 38 ships of the line under French Admiral Pierre- Charles Villeneuve. Ship’s destruction speed during the battle is proportional to the number of enemy ships, on the average any ship can be destroyed for a half of the day. 1. battle • Write the equation. Provide solution depending on time N(t);V (t) graphically. • Who will win? (Victory if number of enemy’s vessels = 0). How many ships should be in order to win the battle? Try system with the following parameters (a12 = 2:5; a21 = 3:8), answer the questions. • How big are the losses, how long the battle lasts? • How can ships’ destruction speed change the result? • What is the process statics (equilibrium point)? • Is the process stable or not? Calculate the eigenvalues of the system. • Provide process trajectory in the state space (N, V) and several more with other initial values (in the same graph). Find eigenvalues of the system. 2 Battle of the Atlantic (World War II) Battle between German submarines (U = 247) and British destroyers (D = 132). Ship’s destruction speed during the battle is proportional to the number of enemy ships, on the average one ship destroys 0.25 of the enemy’s ship per week. Germany produces two submarines a week. • How many destroyers a week to be produced in England in order to achieve victory in the battle? • Provide the equation to solve U(t);D(t). -

From Valmy to Waterloo: France at War, 1792–1815

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-08 - PalgraveConnect Tromsoe i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230294981 - From Valmy to Waterloo, Marie-Cecile Thoral War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors: Rafe Blaufarb (Tallahassee, USA), Alan Forrest (York, UK), and Karen Hagemann (Chapel Hill, USA) Editorial Board: Michael Broers (Oxford, UK), Christopher Bayly (Cambridge, UK), Richard Bessel (York, UK), Sarah Chambers (Minneapolis, USA), Laurent Dubois (Durham, USA), Etienne François (Berlin, Germany), Janet Hartley (London, UK), Wayne Lee (Chapel Hill, USA), Jane Rendall (York, UK), Reinhard Stauber (Klagenfurt, Austria) Titles include: Richard Bessel, Nicholas Guyatt and Jane Rendall (editors) WAR, EMPIRE AND SLAVERY, 1770–1830 Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson (editors) THE BEE AND THE EAGLE Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806 Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann and Jane Rendall (editors) SOLDIERS, CITIZENS AND CIVILIANS Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1820 Karen Hagemann, Gisela Mettele and Jane Rendall (editors) GENDER, WAR AND POLITICS Transatlantic Perspectives, 1755–1830 Marie-Cécile Thoral FROM VALMY TO WATERLOO France at War, 1792–1815 Forthcoming: Michael Broers, Agustin Guimera and Peter Hick (editors) THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE AND THE NEW EUROPEAN POLITICAL CULTURE Alan Forrest, Etienne François and Karen Hagemann -

The Napoleonic Wars by Mark Mclaughlin

R U L E B O O K The Napoleonic Wars By Mark McLaughlin Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................ 2 10. Interception & Evasion .............................. 15 2. Game Components ..................................... 2 11. Battle .......................................................... 15 3. Glossary ...................................................... 3 12. Fortresses .................................................... 17 4. Prepare to Play ........................................... 5 13. Naval Affairs .............................................. 17 5. Sequence of Play ........................................ 6 14. Interphase ................................................... 20 6. Cards & Reserves ....................................... 8 15. Conquest & Submission ............................. 21 7. Builds ......................................................... 9 16. Resources ................................................... 22 8. Diplomacy .................................................. 10 17. Special Rules ............................................... 23 9. Movement .................................................. 13 A Veteran’s Quick Intro to 2nd Edition ............. 24 © 2008 GMT Games, LLC – Version 1.3f The Napoleonic Wars – Version 1.3f Those pieces with a name under the illustration start in that 1. INTRODUCTION named space, although you may substitute any piece of equal This game can be played by two to five players. While defeat value if preferred. Pieces without -

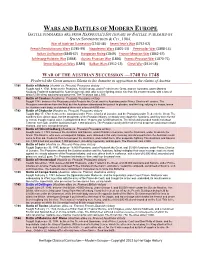

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

“Incorrigible Rogues”: the Brutalisation of British Soldiers in the Peninsular War, 1808-1814

BRUTALISATION OF BRITISH SOLDIERS IN THE PENINSULAR WAR “Incorrigible Rogues”: The Brutalisation of British Soldiers in the Peninsular War, 1808-1814 ALICE PARKER University of Liverpool Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article looks at the behaviour of the British soldiers in the Peninsular War between 1808 and 1814. Despite being allies to Spain and Portugal, the British soldiers committed violent acts towards civilians on a regular basis. Traditionally it has been argued that the redcoat’s misbehaviour was a product of their criminal backgrounds. This article will challenge this assumption and place the soldiers’ behaviour in the context of their wartime experience. It will discuss the effects of war upon soldiers’ mentality, and reflect upon the importance of psychological support in any theatre of war. In 2013 the UK Ministry of Justice removed 309 penal laws from the statute book, one of these being the Vagrancy Act of 1824.1 This Act was introduced for the punishment of ‘incorrigible rogues’ and was directed at soldiers who returned from the Napoleonic Wars and had become ‘idle and disorderly…rogues and vagabonds’.2 Many veterans found it difficult to reintegrate into British society after experiencing the horrors of war at time when the effects of combat stress were not recognised.3 The need for the Act perhaps underlines the degrading effects of warfare upon the individual. The behaviour of British soldiers during the Peninsular War was far from noble and stands in stark contrast to the heroic image propagated in contemporary -

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar Lord Nelson and the early years Horatio Nelson was born in Norfolk in 1758. As a young child he wasn’t particularly healthy but he still went on to become one of Britain’s greatest heroes. Nelson’s father, Edmund Nelson, was the Rector of Burnham Thorpe, the small Norfolk village in which they lived. His mother died when he was only 9 years old. Nelson came from a very big family – huge in fact! He was the sixth of 11 children. He showed an early love for the sea, joining the navy at the age of just 12 on a ship captained by his uncle. Nelson must have been good at his job because he became a captain at the age of 20. He was one of the youngest-ever captains in the Royal Navy. Nelson married Frances Nisbet in 1787 on the Caribbean island of Nevis. Although Nelson was married to Frances, he fell in love with Lady Hamilton in Naples in Italy. They had a child together, Horatia in 1801. Lord Nelson, the Sailor Britain was at war during much of Nelson’s life so he spent many years in battle and during that time he became ill (he contracted malaria), was seriously injured. As well as losing the sight in his right eye he lost one arm and nearly lost the other – and finally, during his most famous battle, he lost his life. Nelson’s job helped him see the world. He travelled to the Caribbean, Denmark and Egypt to fight battles and also sailed close to the North Pole. -

The Napoleonic Wars in Global Perspective

THE NAPOLEONIC WARS IN GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE Jeremy Black Why bother with Napoleon?1 Recently presented as a key figure in the birth of modern warfare,2 in fact he was a failure, not only in hindsight but also in his own lifetime. If there was no perverted Götteradämmerung equivalent to the Berlin bunker of 1945, Napoleon discovered hell in his own terms, impotent, bar in his anger, on an isolated island in the storm- tossed South Atlantic. As a military figure, he failed totally. There was no equivalent to the recovery after the loss of the capital seen with Frederick the Great (Berlin in 1760) or with the Americans, first in the War of Independence (Philadelphia in 1777), and then in the War of 1812 (Washington in 1814). Instead, Napoleon’s return to power in 1815, the Hundred Days, proved short-lived and left France more conclusively defeated as well as occu- pied. In addition, Waterloo was a total defeat for the main field army under Napoleon’s command such as had not happened hitherto, even when he was overcome in 1814: there was no comparable field engage- ment in 1812 to accompany the strategic and operational defeat of the invasion of Russia. Furthermore, Napoleon coped far worse with failure than Louis XIV or Louis XV had done. Louis XIV’s armies had been repeatedly defeated in 1704–9, but the French frontiers largely held. The major fortress of Lille was lost to John, Duke of Marlborough in 1708, after a lengthy siege, but there was no Allied march on Paris and the French were able to fight on. -

The Royal Navy's Blockade System 1793-1805: a Tactical Paradox

The Royal Navy’s Blockade System 1793-1805: A Tactical Paradox Patrick Braszak Throughout the French Revolutionary The Royal Navy’s blockade system Admiral Howe (then the commander-in- and Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain relied counteracted their advantage at sea because chief of the Channel fleet) had put to sea heavily upon its maritime forces, known it discouraged French and Spanish ships from Port St. Helens with twenty-two men- collectively as the Royal Navy. The Royal from leaving port, meaning decisive open- of-war and six frigates in search of a French Navy’s blockade of the European continent water conflicts could not occur.7 The Royal convoy that he had heard was coming back during this period thwarted Napoleon Navy kept a constant presence outside its from North America and the West Indies.13 Bonaparte’s ambitions for the invasion enemy’s ports to prevent hostile expeditions Howe’s intelligence was validated when, on of Great Britain, cut France off from its against Great Britain. By doing so, the British May 19, an American vessel out of Brest overseas resources and facilitated England’s contained their adversaries but allowed them reported that a French fleet composed of rapid imperial and economic growth.1 The to maintain a fleet in being: not active, but twenty-four men-of-war and ten frigates had blockade system, however, only became always ready to become so. The British left two days earlier to protect their valuable a viable strategy once Great Britain had would commit the same tactical error during homeward-bound convoy.14 Outnumbered achieved naval supremacy over France the First World War — despite being under by six ships, Howe nonetheless set off, following the Battle of Trafalgar.