<I>Nerocila Acuminata</I> (Isopoda, Cymothoidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crustacea, Isopoda) from the Indian Ocean Coast of South Africa, with a Key to the Externally Attaching Genera of Cymothoidae

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 889: 1–15 (2019) Bambalocra, a new genus of Cymothoidae 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.889.38638 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A new genus and species of fish parasitic cymothoid (Crustacea, Isopoda) from the Indian Ocean coast of South Africa, with a key to the externally attaching genera of Cymothoidae Niel L. Bruce1,2, Rachel L. Welicky2,3, Kerry A. Hadfield2, Nico J. Smit2 1 Biodiversity & Geosciences Program, Queensland Museum, PO Box: 3300, South Brisbane BC, Queensland 4101, Australia 2 Water Research Group, Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University, Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom, 2520, South Africa 3 School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, 1122 NE Boat Street, Seattle, WA, 98105, USA Corresponding author: Niel L. Bruce ([email protected]) Academic editor: Saskia Brix | Received 30 July 2019 | Accepted 9 October 2019 | Published 14 November 2019 http://zoobank.org/88E937E5-7C48-49F8-8260-09872CB08683 Citation: Bruce NL, Welicky RL, Hadfield KA, Smit NJ (2019) A new genus and species of fish parasitic cymothoid (Crustacea, Isopoda) from the Indian Ocean coast of South Africa, with a key to the externally attaching genera of Cymothoidae. ZooKeys 889: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.889.38638 Abstract Bambalocra intwala gen. et sp. nov. is described from Sodwana Bay, north-eastern South Africa. The monotypic genus is characterised by the broadly truncate anterior margin of the head with a ventral ros- trum, coxae 2–5 being ventral in position not forming part of the body outline and not or barely visible in dorsal view, and the posterolateral margins of pereonites 6 and 7 are posteriorly produced and broadly rounded. -

Diversity and Life-Cycle Analysis of Pacific Ocean Zooplankton by Video Microscopy and DNA Barcoding: Crustacea

Journal of Aquaculture & Marine Biology Research Article Open Access Diversity and life-cycle analysis of Pacific Ocean zooplankton by video microscopy and DNA barcoding: Crustacea Abstract Volume 10 Issue 3 - 2021 Determining the DNA sequencing of a small element in the mitochondrial DNA (DNA Peter Bryant,1 Timothy Arehart2 barcoding) makes it possible to easily identify individuals of different larval stages of 1Department of Developmental and Cell Biology, University of marine crustaceans without the need for laboratory rearing. It can also be used to construct California, USA taxonomic trees, although it is not yet clear to what extent this barcode-based taxonomy 2Crystal Cove Conservancy, Newport Coast, CA, USA reflects more traditional morphological or molecular taxonomy. Collections of zooplankton were made using conventional plankton nets in Newport Bay and the Pacific Ocean near Correspondence: Peter Bryant, Department of Newport Beach, California (Lat. 33.628342, Long. -117.927933) between May 2013 and Developmental and Cell Biology, University of California, USA, January 2020, and individual crustacean specimens were documented by video microscopy. Email Adult crustaceans were collected from solid substrates in the same areas. Specimens were preserved in ethanol and sent to the Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding at the Received: June 03, 2021 | Published: July 26, 2021 University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada for sequencing of the COI DNA barcode. From 1042 specimens, 544 COI sequences were obtained falling into 199 Barcode Identification Numbers (BINs), of which 76 correspond to recognized species. For 15 species of decapods (Loxorhynchus grandis, Pelia tumida, Pugettia dalli, Metacarcinus anthonyi, Metacarcinus gracilis, Pachygrapsus crassipes, Pleuroncodes planipes, Lophopanopeus sp., Pinnixa franciscana, Pinnixa tubicola, Pagurus longicarpus, Petrolisthes cabrilloi, Portunus xantusii, Hemigrapsus oregonensis, Heptacarpus brevirostris), DNA barcoding allowed the matching of different life-cycle stages (zoea, megalops, adult). -

Trends and Gaps on Philippine Scombrid Research: a Bibliometric Analysis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.30.450467; this version posted July 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Trends and Gaps on Philippine Scombrid Research: A bibliometric analysis ┼ ┼ Jay-Ar L. Gadut1 , Custer C. Deocaris2,3 , and Malona V. Alinsug2,4* 1 Science Department, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Mindanao State University- General Santos City 9500, Philippines 2Philippine Nuclear Research Institute, Department of Science and Technology, Commonwealth Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 3 Research and Development Management Office, Technological Institute of the Philippines, Cubao, Quezon City, Philippines 4 School of Graduate Studies, Mindanao State University-General Santos City 9500, Philippines ┼ These authors contributed equally to the paper. *Corresponding Author: [email protected] or [email protected] Agricultural Research Section, Philippine Nuclear Research Institute Department of Science and Technology, Commonwealth Avenue, Quezon City, Philippines 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.30.450467; this version posted July 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. ABSTRACT Philippine scombrids have been among the top priorities in fisheries research due primarily to their economic value worldwide. Assessment of the number of studies under general themes (diversity, ecology, taxonomy and systematics, diseases and parasites, and conservation) provides essential information to evaluate trends and gaps of research. -

Cymothoidae from Fishes of Kuwait (Arabian Gulf) (Crustacea: Isopoda)

Cymothoidae from Fishes of Kuwait (Arabian Gulf) (Crustacea: Isopoda) THOMAS E. BOWMAN and INAM U. TAREEN SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 382 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropo/ogy Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world cf science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Invertebrate ID Guide

11/13/13 1 This book is a compilation of identification resources for invertebrates found in stomach samples. By no means is it a complete list of all possible prey types. It is simply what has been found in past ChesMMAP and NEAMAP diet studies. A copy of this document is stored in both the ChesMMAP and NEAMAP lab network drives in a folder called ID Guides, along with other useful identification keys, articles, documents, and photos. If you want to see a larger version of any of the images in this document you can simply open the file and zoom in on the picture, or you can open the original file for the photo by navigating to the appropriate subfolder within the Fisheries Gut Lab folder. Other useful links for identification: Isopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-33/htm/doc.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-48/htm/doc.html Polychaetes http://web.vims.edu/bio/benthic/polychaete.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-34/htm/doc.html Cephalopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-44/htm/doc.html Amphipods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-67/htm/doc.html Molluscs http://www.oceanica.cofc.edu/shellguide/ http://www.jaxshells.org/slife4.htm Bivalves http://www.jaxshells.org/atlanticb.htm Gastropods http://www.jaxshells.org/atlantic.htm Crustaceans http://www.jaxshells.org/slifex26.htm Echinoderms http://www.jaxshells.org/eich26.htm 2 PROTOZOA (FORAMINIFERA) ................................................................................................................................ 4 PORIFERA (SPONGES) ............................................................................................................................................... 4 CNIDARIA (JELLYFISHES, HYDROIDS, SEA ANEMONES) ............................................................................... 4 CTENOPHORA (COMB JELLIES)............................................................................................................................ -

Crustacea, Isopoda, Cymothoidae) from Indian Marine Fishes

Parasitol Res (2013) 112:1273–1286 DOI 10.1007/s00436-012-3263-5 ORIGINAL PAPER Nerocila species (Crustacea, Isopoda, Cymothoidae) from Indian marine fishes Jean-Paul Trilles & Ganapathy Rameshkumar & Samuthirapandian Ravichandran Received: 18 September 2012 /Accepted: 17 December 2012 /Published online: 17 January 2013 # The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Eleven Nerocila species are recorded from 22 ma- 1999) and sometimes even on several other organisms rine fishes belonging to 15 families. Three, Nerocila arres, (Trilles and Öktener 2004; Wunderlich et al. 2011). Nerocila depressa,andNerocila loveni, are new for the Indian Nerocila is a large genus of the family Cymothoidae fauna. N. arres and Nerocila sigani, previously synonymized, including at least 65 species living attached on the skin or are redescribed and their individuality is restored. Nerocila on the fins of fishes. As already reported by Trilles (1972, exocoeti, until now inadequately identified, is described and 1979), Williams and Williams (1980, 1981), and Bruce distinctly characterized. A neotype is designated. New hosts (1987a, b), several species are morphologically highly var- were identified for N. depressa, N. loveni, Nerocila phaio- iable and their identification is often difficult. The variabil- pleura, Nerocila serra,andNerocila sundaica. Host–parasite ity was particularly studied in Nerocila armata and Nerocila relationships were considered. The parasitologic indexes were orbignyi (Monod 1931), Nerocila excisa (Trilles 1972), calculated. The site of attachment of the parasites on their hosts Nerocila sundaica (Bowman 1978), Nerocila acuminata was also observed. A checklist of the nominal Nerocila species (Brusca 1981), Nerocila arres,andNerocila kisra until now reported from Indian marine fishes was compiled. -

Nerocila Sp. (Isopoda: Cymothoidae) Parasitizing Mugil Liza (Teleostei: Mugilidae) in São Francisco Do Sul, Santa Catarina, Brazil

Biotemas, 31 (1): 41-44, março de 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-7925.2018v31n1p4141 ISSNe 2175-7925 Short Communication Nerocila sp. (Isopoda: Cymothoidae) parasitizing Mugil liza (Teleostei: Mugilidae) in São Francisco do Sul, Santa Catarina, Brazil Juliano Santos Gueretz 1 Lucas Cardoso 2 Maurício Laterça Martins 2 Antonio Pereira de Souza 1 1 Instituto Federal Catarinense, Campus Araquari Rodovia BR 280, km 27, CEP 89.245-000 Araquari – SC, Brasil 2 Laboratório AQUOS – Sanidade de Organismos Aquáticos Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis – SC, Brasil * Autor para correspondência [email protected] Submetido em 04/08/2017 Aceito para publicação em 21/11/2017 Resumo Nerocila sp. (Isopoda: Cymothoidae) parasite of Mugil liza (Teleostei: Mugilidae) capturado em São Francisco do Sul, estado de Santa Catarina, Brasil. Isópodes da família Cymothoidae são ectoparasitos de peixes, com baixa especificidade de hospedeiros, comumente encontrados fixados nas brânquias, boca, cavidade opercular, narinas e tegumento de ampla variedade de hospedeiros. Os danos causados são variáveis em função do grau de parasitismo e do sítio de infestação e podem provocar desconforto respiratório nos hospedeiros. O objetivo deste estudo foi relatar a ocorrência do isópode Nerocila sp. Leach, 1818 parasitando Mugil liza Valenciennes, 1836, capturada na Baía da Babitonga, estado de Santa Catarina, Brasil. Uma fêmea de 24 mm de comprimento e 11 mm de largura contendo ovos de 1.18 ± 0.08 x 1.03 ± 0.06 mm, foi encontrada na nadadeira peitoral de M. liza. Palavras-chave: Baía da Babitonga; Crustáceo; Parasito; Tainha Abstract Isopods from the family Cymothoidae are fish ectoparasites displaying low host specificity found commonly attached to the gills, mouth, opercular cavity, nostrils and body surface of several host species. -

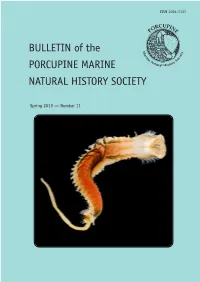

PMNHS Bulletin Number 11, Spring, 2019

ISSN 2054-7137 BULLETIN of the PORCUPINE MARINE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY Spring 2019 — Number 11 Bulletin of the Porcupine Marine Natural History Society No. 11 Spring 2019 Hon. Chairman — Susan Chambers Hon. Secretary — Frances Dipper [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Hon. Treasurer — Fiona Ware Hon. Membership Secretary — Roni Robbins [email protected] [email protected] Hon. Editor — Vicki Howe Hon. Records Convenor — Julia Nunn [email protected] [email protected] Newsletter Layout & Design Hon. Web-site Officer — Tammy Horton — Teresa Darbyshire [email protected] [email protected] Aims of the Society Ordinary Council Members • To promote a wider understanding of the Peter Barfield [email protected] biology, ecology and distribution of marine Sarah Bowen [email protected] organisms. Fiona Crouch [email protected] • To stimulate interest in marine biodiversity, Becky Hitchin [email protected] especially in young people. Jon Moore [email protected] • To encourage interaction and exchange of information between those with interests in different aspects of marine biology, amateur and professional alike. Porcupine MNHS welcomes new members - http://www.facebook.com/groups/190053525989 scientists, students, divers, naturalists and all @PorcupineMNHS those interested in marine life. We are an informal society interested in marine natural history and recording, particularly in the North Atlantic and ‘Porcupine Bight’. Members receive 2 Bulletins per year (individuals www.pmnhs.co.uk can choose to receive either a paper or pdf version; students only receive the pdf) which include proceedings from scientific meetings, field visits, observations and news. -

Crustacean Research 46 Crustacean Research 46 a CYMOTHOID ISOPOD in FISH MARICULTURE

Crustacean Research 2017 Vol.46: 95–101 ©Carcinological Society of Japan. doi: 10.18353/crustacea.46.0_95 Nerocila phaiopleura, a cymothoid isopod parasitic on Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, cultured in Japan Kazuya Nagasawa, Sho Shirakashi Abstract.̶ Ovigerous females of Nerocila phaiopleura Bleeker, 1857 were collected from the body surface of young Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844), cultured in Japan. This represents the first record of N. phaiopleura in finfish mariculture. The species is the third cymothoid isopod from maricultured fishes in Japan. The infected fish had a large hemorrhagic wound caused by N. phaio- pleura at the attachment site. Thunnus orientalis is a new host of the isopod. No cy- mothoid infection has so far been reported from wild individuals of T. orientalis that swims at high speeds in the oceans, and the observed occurrence of N. phaiopleura on this fish species is regarded as unusual under confined mariculture conditions. The hosts and geographical distribution records of N. phaiopleura in Japan are reviewed. Key words: fish parasite, fish mariculture, new host record Recently, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus ori- mar et al., 2016). This is the first report of N. entalis (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844), is abun- phaiopleura in finfish mariculture. dantly cultured in Japanese coastal waters The isopods were collected from two (Yamamoto, 2012), with a production of 14726 individuals of six young T. orientalis (176– metric tons in 2015 (Anonymous, 2016). How- 259 mm in standard length) examined from ever, due to a short history of aquaculture of T. floating rectangular net-cages (12 m sides and orientalis in Japan, much remains poorly un- 5 m deep) in coastal waters of the north- derstood on its parasites. -

Isopoda, Cymothoidae), Crustacean Parasites of Marine Fishes, with Descriptions of Eastern Australian Species.Records of the Australian Museum 42(3): 247–300

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Bruce, Niel L., 1990. The genera Catoessa, Elthusa, Enispa, Ichthyoxenus, Idusa, Livoneca and Norileca n.gen. (Isopoda, Cymothoidae), crustacean parasites of marine fishes, with descriptions of eastern Australian species.Records of the Australian Museum 42(3): 247–300. [16 November 1990]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.42.1990.118 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia Records of the Australian Museum (1990) Vol. 42: 247-300. ISSN 0067-1975 247 The Genera Catoessa, Elthusa, Enispa, Ichthyoxenus, Idusa, Livoneca and Norileca n.gen. (Isopoda, Cymothoidae), Crustacean Parasites of Marine Fishes, with Descriptions of Eastern Australian Species NIEL L. BRUCE Australian Museum, PO Box A2S5, Sydney South, NSW 2000, Australia Present address: Queensland Museum, PO Box 300, South Brisbane, Qld 4101, Australia ABSTRACT. The following genera of Cymothoidae are recorded from Australia: Catoessa Schiodte & Meinert, Elthusa SchiOdte & Meinert, Enispa SchiOdte & Meinert, Ichthyoxenus Herklots, Livoneca Leach and Norileca n.gen. Full diagnoses are given for Enispa, Livoneca and Norileca n.gen. For the remaining genera provisional diagnoses are given. Idusa SchiOdte & Meinert is rediagnosed to allow separation from Catoessa. All the species described herein would have previously been placed in Livoneca. Examination of the type material of L. redmanii shows that all other species placed in the genus, except for L. bowmani Brusca, are not congeners, and are reassigned, where possible, to other genera. -

Global Diversity of Fish Parasitic Isopod Crustaceans of the Family

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Review Global diversity of fish parasitic isopod crustaceans of the family Cymothoidae ⇑ Nico J. Smit a, , Niel L. Bruce a,b, Kerry A. Hadfield a a Water Research Group (Ecology), Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North West University, Potchefstroom Campus, Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa b Museum of Tropical Queensland, Queensland Museum and School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, 70–102 Flinders Street, Townsville 4810, Australia article info abstract Article history: Of the 95 known families of Isopoda only a few are parasitic namely, Bopyridae, Cryptoniscidae, Received 7 February 2014 Cymothoidae, Dajidae, Entoniscidae, Gnathiidae and Tridentellidae. Representatives from the family Revised 19 March 2014 Cymothoidae are obligate parasites of both marine and freshwater fishes and there are currently 40 Accepted 20 March 2014 recognised cymothoid genera worldwide. These isopods are large (>6 mm) parasites, thus easy to observe Available online xxxx and collect, yet many aspects of their biodiversity and biology are still unknown. They are widely distributed around the world and occur in many different habitats, but mostly in shallow waters in Keywords: tropical or subtropical areas. A number of adaptations to an obligatory parasitic existence have been Isopoda observed, such as the body shape, which is influenced by the attachment site on the host. Cymothoids Biodiversity Parasites generally have a long, slender body tapering towards the ends and the efficient contour of the body offers Cymothoidae minimum resistance to the water flow and can withstand the forces of this particular habitat. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The effects of parasites on the kelp-forest food web Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/43k56121 Author Morton, Dana Nicole Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The effects of parasites on the kelp-forest food web A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology by Dana Nicole Morton Committee in charge: Professor Armand M. Kuris, Chair Professor Mark H. Carr, UCSC Professor Douglas J. McCauley Dr. Kevin D. Lafferty, USGS/Adjunct Professor March 2020 The dissertation of Dana Nicole Morton is approved. ____________________________________________ Mark H. Carr ____________________________________________ Douglas J. McCauley ____________________________________________ Kevin D. Lafferty ____________________________________________ Armand M. Kuris, Committee Chair March 2020 The effects of parasites on the kelp-forest food web Copyright © 2020 by Dana Nicole Morton iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I did not complete this work in isolation, and first express my sincerest thanks to many undergraduate volunteers: Cristiana Antonino, Glen Banning, Farallon Broughton, Allison Clatch, Melissa Coty, Lauren Dykman, Christian Franco, Nora Frank, Ali Gomez, Kaylyn Harris, Sam Herbert, Adolfo Hernandez, Nicky Huang, Michael Ivie, Conner Jainese, Charlotte Picque, Kristian Rassaei, Mireya Ruiz, Deena Saad, Veronica Torres, Savanah Tran, and Zoe Zilz. I would also like to thank Ralph Appy, Bob Miller, Clint Nelson, Avery Parsons, Christoph Pierre, and Christian Orsini for donating specimens to this project and supporting my own sample collection. I also thank Jim Carlton, Milton Love, David Marcogliese, John McLaughlin, and Christoph Pierre for sharing their expertise in thoughtful discussions on this work.