R. Blust Proto-Western Malayo-Polynesian Vocatives In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Festschrift for Robert Blust

Austronesian historical linguistics and culture history: a festschrift for Robert Blust Edited by Alexander Adelaar and Andrew Pawley Pacific Linguistics Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Table of contents Contributors to this volume x Acknowledgements xiii Parti: About Bob 1 Reflections on Bob Blust's career Alexander ADELAAR and Andrew PAWLEY 3 2 Feting Bob's career to date Byron W. BENDER 17 3 Thoughts on learning that Bob Blust has reached festschrift age George W. GRACE 19 4 The publications of Robert A. Blust 23 Part 2: Sound change 5 Structure-preserving sound change: a look at unstressed vowel syncope in Austronesian Juliette BLEVINS 39 6 Irregular sound change and the post-velars in some Malakula languages John LYNCH 57 7 In search of an historical Sea-People Malay dialect with -aba- Waruno MAHDI 73 8 The sounds of Southeast Babar Hein STE1NHAUER 91 9 Motherese and historical implications Shigeru TSUCHIDA 107 10 The Proto Austronesian laryngeal John WOLFF 115 vii Vlll Part 3: Grammatical change and typology 11 The various origins of the passive prefix di- Alexander ADELAAR 129 12 Relative-clause bracketing in Oceanic languages around the Huon Gulf of New Guinea Joel BRADSHAW 143 13 The history of the Tukang Besi pronominals MarkDONOHUE 163 14 Verbal aspect and personal pronouns: the history of aorist markers in north Vanuatu Alexandre FRANCOIS 179 15 Austronesian typology and the nominalist hypothesis Daniel KAUFMAN 197 16 Start and finish: some grammatical changes in Toqabaqita Frantisek -

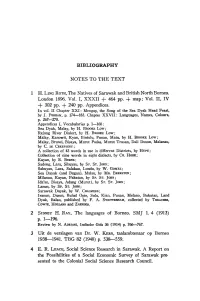

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission

MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION INVITATION TO REGISTER INTEREST AND SUBMIT A DRAFT UNIVERSAL SERVICE PLAN AS A UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVIDER UNDER THE COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA (UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVISION) REGULATIONS 2002 FOR THE INSTALLATION OF NETWORK FACILITIES AND DEPLOYMENT OF NETWORK SERVICE FOR THE PROVISIONING OF PUBLIC CELLULAR SERVICES AT THE UNIVERSAL SERVICE TARGETS UNDER THE JALINAN DIGITAL NEGARA (JENDELA) PHASE 1 INITIATIVE Ref: MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Date: 20 November 2020 Invitation to Register Interest as a Universal Service Provider MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Page 1 of 142 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. 4 INTERPRETATION ........................................................................................................................... 5 SECTION I – INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 8 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 8 SECTION II – DESCRIPTION OF SCOPE OF WORK .............................................................. 10 2. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FACILITIES AND SERVICES TO BE PROVIDED ....................................................................................................................................... 10 3. SCOPE OF -

Patricia Spyer

Patricia Spyer PATRICIA SPYER Curriculum Vitae 2021 Research Interests Areal: Southeast Asia (Indonesia) Topical: Socio-cultural theory, visual and material culture, media, aesthetics, violence, religion and ritual, colonial and postcolonial societies, archives, history and historical consciousness, modernity Education 1981-92 University of Chicago, Department of Anthropology Ph.D Dissertation: "The Memory of Trade: circulation, autochthony, and the past in the Aru Islands (eastern Indonesia)" Committee: Valerio Valeri (Chair), Bernard Cohn, Nancy Munn, Marshall Sahlins M.A. 1984 Thesis: "Hunting Heads for Alliance: The Recreation of a Moral Order in Atoni Exchange" Thesis advisors: Valerio Valeri, Nancy Munn 1977-81 Tufts University, B.A. Anthropology and History Major Magna Cum Laude 1980 Archeological Summer Field School, University of New Mexico. 1976-1977 Studies in French Language and Culture, Université de Provence. Aix-en-Provence, France 1970-1976 Baccalaureat Atheneum A, Montessori Lyceum. Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Final examinations completed in Dutch, English, French, German, Latin, History and Economics Teaching Experience 2016- Professor of Anthropology, Graduate Institute Geneva 2017 Organizer, with Rafael Sánchez, “In the Thick of Images or Visual Anthropology Today,” CUSO (Conférence Universitaire de Suisse Occidentale) Doctoral Seminar, Castasegna, Switzerland, April 2001-15 Professor of Anthropology of Contemporary Indonesia, Leiden University 2015 Summer School, Excellenz Cluster “Asia-Europe, Heidelberg University, -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

Gotong Royong: a Study of an Indonesian Concept and the Application of Its Principles to the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Indonesia

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 1975 Gotong Royong: A Study Of An Indonesian Concept And The Application Of Its Principles To The Seventh-Day Adventist Church In Indonesia Jan Manaek Hutauruk Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Hutauruk, Jan Manaek, "Gotong Royong: A Study Of An Indonesian Concept And The Application Of Its Principles To The Seventh-Day Adventist Church In Indonesia" (1975). Dissertation Projects DMin. 354. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/354 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary GOTONG ROYONG: A STUDY OF AN INDONESIAN CONCEPT AND THE APPLICATION OF ITS PRINCIPLES TO THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN INDONESIA A Project Report Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry by Jan Manaek Hutauruk March 1975 Approval ACKNOWLEDGEMENT A work of this kind is a work of dependence. Without the support of several important people this study would have been impossible. Truly what the author has accomplished is the result of gotong royong— a group work. Dr. Gottfried Oosterwal has given the author guidance, advice, and encouragement; Dr. Robert Johnston has read the paper through and given his criticism to improve it; Dr. -

1.0 TUJUAN C) Perisytiharan Senarai Kawasan Pedalamannegeri Terkini

JABATAN KETUA MENTERl UNIT PENGURUSAN SUMBER MANUSIA TINGKAT 10 & 11, WISMA BAPA MALAYSIA, Telefon Am: 082-441957 PETRA JAY A, Kawat: SUK KUCHING 93502 KUCHING, Faks : 082-445618&312549 SARAWAK. SURAT PEKELILING (Perj. BiI.23/2006) Semua Ketua Jabatan Negeri DARIPADA: Setiausaha Kerajaan, KEP ADA: Sarawak. Semua Setiausaha Tetap Kementerian Semua Residen dan Pegawai Daerah Semua Ketua Badan Berkanun Negeri Semua Ketua Pihak Berkuasa Tempatan Negeri PERKARA: Kawasan Pedalaman SALINAN Ketua Pengarah Perkhidmatan Awarn, Negeri Sarawak KEPADA: Malaysia Ketua Setiausaha Kementerian Kewangan, Malaysia Setiausaha Persekutuan Sarawak Pesuruhjaya Polis DiRaja Malaysia Pengarah Pelajaran Negeri Pengarah Kesihatan Negeri Pengarah Imigresen Sarawak Pengarah Audit Negeri RUJUKAN: 63 /EO/I079/Jld.13 TARIKH: is Disember 2006 1.0 TUJUAN Surat Pekeliling ini bertujuan untuk memaklumkan keputusan Kerajaan Negeri ke atas perkara- perkara beriku t:- a) keputusan menerimapakai Pekeliling Perkhidmatan Bilangan 5 Tahun 2000 : Bayaran Insentif Pedalaman tetapi masih mengekalkan 3 kriteria sedia ada di perenggan 5.1.1, 5.1.2 dan 5.1.3 Surat Pekeliling (Perj. Bil. 21/1997) sesuai dengan ciri-ciri geografi Negeri Sarawak yang 'unique' dan keadaan di tempat-tempat terpencil berbeza dari temp?t-tempat terpencil di Semenanjung Malaysia. b) Kawasan Pedalaman yang layak diisytiharkan hanya perlu memenuhi dua (2) dan tiga (3) syarat utama kriteria sedia ada seperti di perenggan 5.1.1, 5.1.2 dan 5.1.3 Surat Pekeliling (Perj. Bil. 21/1997). Walau bagaimanapun, dengan memenuhi satu dari syarat-syarat kecil di bawah syarat-syarat utama dianggap memenuhi syarat-syarat utama berkenaan. c) perisytiharan Senarai Kawasan Pedalaman Negeri terkini adalah seperti di Lampiran A. -

A Phylogenetic Approach to Comparative Linguistics: a Test Study Using the Languages of Borneo

Hirzi Luqman 1st September 2010 A Phylogenetic Approach to Comparative Linguistics: a Test Study using the Languages of Borneo Abstract The conceptual parallels between linguistic and biological evolution are striking; languages, like genes are subject to mutation, replication, inheritance and selection. In this study, we explore the possibility of applying phylogenetic techniques established in biology to linguistic data. Three common phylogenetic reconstruction methods are tested: (1) distance-based network reconstruction, (2) maximum parsimony and (3) Bayesian inference. We use network analysis as a preliminary test to inspect degree of horizontal transmission prior to the use of the other methods. We test each method for applicability and accuracy, and compare their results with those from traditional classification. We find that the maximum parsimony and Bayesian inference methods are both very powerful and accurate in their phylogeny reconstruction. The maximum parsimony method recovered 8 out of a possible 13 clades identically, while the Bayesian inference recovered 7 out of 13. This match improved when we considered only fully resolved clades for the traditional classification, with maximum parsimony scoring 8 out of 9 possible matches, and Bayesian 7 out of 9 matches. Introduction different dialects and languages. And just as phylogenetic inference may be muddied by horizontal transmission, so “The formation of different languages and of distinct too may borrowing and imposition cloud true linguistic species, and the proofs that both have been developed relations. These fundamental similarities in biological and through a gradual process, are curiously parallel... We find language evolution are obvious, but do they imply that tools in distinct languages striking homologies due to community and methods developed in one field are truly transferable to of descent, and analogies due to a similar process of the other? Or are they merely clever and coincidental formation.. -

Languages of Malaysia (Sarawak)

Ethnologue report for Malaysia (Sarawak) Page 1 of 9 Languages of Malaysia (Sarawak) Malaysia (Sarawak). 1,294,000 (1979). Information mainly from A. A. Cense and E. M. Uhlenbeck 1958; R. Blust 1974; P. Sercombe 1997. The number of languages listed for Malaysia (Sarawak) is 47. Of those, 46 are living languages and 1 is extinct. Living languages Balau [blg] 5,000 (1981 Wurm and Hattori). Southwest Sarawak, southeast of Simunjan. Alternate names: Bala'u. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Malayic, Malayic-Dayak, Ibanic More information. Berawan [lod] 870 (1981 Wurm and Hattori). Tutoh and Baram rivers in the north. Dialects: Batu Bla (Batu Belah), Long Pata, Long Jegan, West Berawan, Long Terawan. It may be two languages: West Berawan and Long Terawan, versus East-Central Berawang: Batu Belah, Long Teru, and Long Jegan (Blust 1974). Classification: Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Northwest, North Sarawakan, Berawan-Lower Baram, Berawan More information. Biatah [bth] 21,219 in Malaysia (2000 WCD). Population total all countries: 29,703. Sarawak, 1st Division, Kuching District, 10 villages. Also spoken in Indonesia (Kalimantan). Alternate names: Kuap, Quop, Bikuab, Sentah. Dialects: Siburan, Stang (Sitaang, Bisitaang), Tibia. Speakers cannot understand Bukar Sadong, Silakau, or Bidayuh from Indonesia. Lexical similarity 71% with Singgi. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Land Dayak More information. Bintulu [bny] 4,200 (1981 Wurm and Hattori). Northeast coast around Sibuti, west of Niah, around Bintulu, and two enclaves west. Dialects: Could also be classified as a Baram-Tinjar Subgroup or as an isolate within the Rejang-Baram Group. Blust classifies as an isolate with North Sarawakan. Not close to other languages. -

North Borneo, Pontianak, Bandjermasin, Dyak, Iban and Other Geographical and Ethnic Names Related to the Island

CHECKLIST OF HOLDINGS ON BORNEO ·i· IN THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES THE CORNELL UN·IVERSITY S0trrHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies (now the Department of Asian Studies) in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaya, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs, and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on the area's Chinese minorities. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program office is given at the end of this volume. Information on the Program staff, fellow ships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings will be found in an Announcement of the Department of Asian Studies, obtain able from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, Franklin Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14850. CHECKLIST OF HOLDIR;S ON BORNEO IN THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Compiled by Michael B. -

Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Robert Blust University of Hawai‘I, Honolulu, Hawai‘I, [email protected]

Human Biology Volume 85 Issue 1 Special Issue on Revisiting the "Negrito" Article 18 Hypothesis 2013 Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Robert Blust University of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Blust, Robert (2013) "Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past," Human Biology: Vol. 85: Iss. 1, Article 18. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol85/iss1/18 Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Abstract Within recorded history. most Southeast Asian peoples have been of "southern Mongoloid" physical type, whether they speak Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, Austronesian, Tai-Kadai, or Hmong-Mien languages. However, population distributions suggest that this is a post-Pleistocene phenomenon and that for tens of millennia before the last glaciation ended Greater Mainland Southeast Asia, which included the currently insular world that rests on the Sunda Shelf, was peopled by short, dark-skinned, frizzy-haired foragers whose descendants in the Philippines came to be labeled by the sixteenth-century Spanish colonizers as "negritos," a term that has since been extended to similar groups throughout the region. There are three areas in which these populations survived into the present so as to become part of written history: the Philippines, the Malay Peninsula, and the Andaman Islands. All Philippine negritos speak Austronesian languages, and all Malayan negritos speak languages in the nuclear Mon-Khmer branch of Austroasiatic, but the linguistic situation in the Andamans is a world apart.