General Sir Charles Napier's Administration of Scinde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Summer BG News July 19, 1979

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 7-19-1979 The Summer BG News July 19, 1979 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The Summer BG News July 19, 1979" (1979). BG News (Student Newspaper). 3638. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/3638 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. the summer ,Bowlinq 'Green Stole University Musical Arts Center's performance hall I named after Kobacker hy Diane Must based chain of retail shoe cording to Kim Kreiger, stores. director of music events and The 850-seat concert hall Moore said the Kobacker promotions at the Univer- and theater in the new family gift to the University sity. Musical Arts Center was was the largest donation to Other featuresof the Center named the Lenore and the Center. A $7.5 million are its 88 practice rooms, 68 Marvin Kobacker Hall state appropriation and a studios and offices, two Thursday, July 12. private fund-raising cam- rehearsal rooms, and an * 1 University President Dr. paign is being used to electronic music recording Hollis A. Moore Jr. made the finance the $9 million studio and classroom. announcement at a luncheon building. Architects for the Center which was attended by the are Bauer, Stark and Lash- Kobacker family, University Kobacker is a past brook of Toledo. -

The Image of Police Officer As Emerging from Road Movies and Road Lingo

ZESZYTY NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU RZESZOWSKIEGO SERIA FILOLOGICZNA ZESZYT 51/2008 STUDIA ANGLICA RESOVIENSIA 5 Grzegorz A. KLEPARSKI, Magorzata MARTYNUSKA THE IMAGE OF POLICE OFFICER AS EMERGING FROM ROAD MOVIES AND ROAD LINGO Road movies: The roots of the genre American society holds many things to be dear – indeed one might say that, becoming to such a heterogenous notion these notions are equally varied. However, one might define a number of values which are commonly held to be of great importance to America as a whole, such as mobility, independence, fairness, individualism, freedom, determination and courage. These values are best encapsulated in the film genre known as ‘road movies’, through which Hollywood has sought to celebrate the very nature of Americanness. The purpose set to the pages that follow is to outline the concept of freedom as the guiding force of the characters in the road movies and – in particular – the role and the concept of POLICE OFFICER who either turns out to be a constraint on freedom or – on rare occasions – its facilitator. The second part of the paper concerns the trucker language, and – more specifically – the picture of the POLICE OFFICER in the language of CB radio. In particular, we shall analyse the linguistic mechanisms involved in shaping the concept discussed; that is the working of the devices of zoosemy and metonymy. From the very outset, it can be observed that right from the very origins of settlement in the New World, the first Americans were always connected – in some way – with the road and the concept of travelling.1 The early settlers were pioneers wandering westwards; crossing wide stretches of land, constantly on the move in search of a place to live. -

Sir Charles Napier

englt~fJ atlnl of Xlction SIR CHARLES NAPIER I\I.~~III SIR CHARLES NAPIER. SIR CHARLES NAPIER BY COLONEL SIR WILLIAM F.BUTLER 3ionbon MACMILLAN AND cn AND NEW YORK 1890 .AU rlgjts f'<8erved CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAOB THI HOME AT CELBRIDGE--FIRST COllMISSION CHAPTER II EARLY SEBVICE--THE PENINSULA. 14 CHAPTER III CoRUIIINA 27 CHAPTER IV THE PENINSULA IN 1810-11-BEIUIUDA-AMERICA -RoYAL MILITARY COLLEGE. 46 CHAPTER V CEPHALONIA 62 • CHAPTER VI OUT OF HARNESS 75 vi CONTENTS CHAPTER VII PAOK COlWA..'ID OJ' THE NORTHERN DISTRICT • 86 CHAPTER VIII bmIA-THE WAR IN Scn.""DE 98 CHAPTER IX . ~.17 CHAPTER X THE MORROW OJ' lliANEE-THE ACTION AT DUBBA 136 CHAPTER XI THE ADHINISTRATION OJ' ScnlDE • • 152 CHAPTER XII ENGLAND--1848 TO 1849 175 CHAPTER XIII ColDlANDER-IN-CHlEl!' IN INDIA 188 CHAPTER XIV HOKE-LAsT ILLNESS-DEATH THE HOldE AT CELBRIDGE-FIRST COMMISSION • TEN miles west of Dublin, on the north bank of the Liffey, stands a village of a single street, called Celbridge. In times so remote that their record only survives in a name, some Christian hermit built here himself a cell for house, church, and tomb; a human settlement took root around the spot; deer-tracks' widened into pathways; pathways broadened into roads; and at last a bridge spanned the neighbouring stream. The church and the bridge, two prominent land-marks on the road of civilisation, jointly named the place, and Kildrohid or "the church by the bridge" became hence forth a local habitation and a name, twelve hundred years later to be anglicised into. -

LP Open HOY Points

2006 Little Pack Open HOY Points SANGAMO MAX MATT ELLIOTT 883.8 COTTON CHASE SMOKER JOSHUA FIELDS 114.8 WINDY RIDGE NICK'S MISSIE MARK BROWN 646.7 GULLO'S GREAT GATES OF GATOR GEORGE D GULLO 114 GOODTIME'S UNO W W KENNEL 492 HEEHAN'S TOP GUNNER WILL LEFEVERS 113.7 HOWARD'S BANDIT DANNY VANSICKLE 409.4 WHIPPOORWILL CREEK LIGHT'S JL WHIPPOORWILL CREEK 111.9 BIG MEADOWS SUPERMAN DENNIS KENNEDY 397.2 KENNEL L & L OL RED RUSTY LYONS 358.7 C & K BRANDY CHARLES PUCKETT 111.6 AJ'S CHOPPIN MAGGIE JEFF HAYNES & PAUL 349 STONE'S KT KEVIN STONE 110.5 BONHAM HALL'S FRECKLES PHILLIP THACKER 110.4 SCROGHAM KY REGGIE KEVIN MONROE 348 FOX CREEK'S COBRA RONALD D RUMMER 110.3 NIDA'S JAKE MELVIN NIDA 341.2 DIAMOND P'S LIGHTING STORM DANNY & ETHAN MADEWELL 110.3 SUPER SPORT SING ME THE BLUES JEFFREY S BROWN 337.3 KLAIBER'S SWINGING BRUISER RALPH KLAIBER 109.9 CHOIR HILL BILLY TWIN PINES BEAGLES 327.4 TRIPLE W'S MISS LIZZY HILL'S SHAKERAG KENNEL 108.4 STATEN'S REDBRUSH BUDDY ABC KENNEL 311 KISS' GHOST OF THE SWAMP DERALD BOMAN 108 TRIPLE A'S BROWNING WILSON CREEK TRIPLE A 306.3 OSBORNE'S SPADE CHRIS BRYANT 108 KENNEL SANDMAN'S DREAMCATCHER JOSEPH J MURPHY 108 BRANKO'S HAPPY FELLER MARK BROWN 300.8 COCHRAN'S BOOGER CHARLIE COCHRAN 107.6 ABSHIRE'S LEREE RD JEW KNEE JIMMIE ABSHIRE 283.1 DAVID MEDLIN TOUGH MAN DAVID MEDLIN 107.3 POE'S TURBO POWERED APACHE KEVIN MONROE 282 SMITH'S WEEDEATER CROW J D CASEY 107.2 HOLLYWOOD'S MACK WALHONDING VALLEY 248.7 MIDDLE RIDGE JAKE JARROD KILE 107 KENNEL BRANKO'S RINGO STAR TRACY SKILES 106.7 BLACK POINT BREAKER JACK COE 203.8 -

Annual Financial Report 2011-2012

ROCKCASTLE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION UNAUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENT For Year Endin June 30 2012 Demand Deposit Account $1,480,996.98 Outstanding Checks ($815,446.69) Investments $5,000,000.00 Ledger Balance (all funds) $5,665,550.29 Accounts Receivable $716,087.76 Food Service Inventory $43,820.00 Deferred Revenue ($257,310.25' Accounts Payable ($176,854.26) Accrued Salaries & Benefits Payable ($132,059.36) FUND BALANCE (all funds) $5,859,234.18 This is to certify that all Financial Statements as listed are accurate. JKelanie JIll. ~ August 8,2012 Melanie M. Lyons (Date) Rockcastle County Board of Education Treasurer [finstmtI2website] 08/20/2012 21:49 !ROCKCASTLE COUNTY SCHOOLS I PG 1 9511mlyo IANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR FY 2012 Iglkyafrp YR TO DATE % r.:FI\IFRtd FUND (1) ACTUAL ______ USED REVENUES 0999 BEGINNING BALANCE TOTAL 0999 BEGINNING BALANCE 3,803,176.21 3,803,176.21 .00 100.00 RECEIPTS REVENUE FROM LOCAL SOURCES AD VALOREM TAXES 1111 GENERAL PROPERTY TAX 1,250,000.00 1,235,053.13 14,946.87 98.80 1112 GENERAL PERS PROPERTY TAX .00 .00 .00 .00 1113 PSC PROPERTY TAX 175,000.00 165,266.23 9,733.77 94.44 1114 PSC PERS PROPERTY TAX .00 .00 .00 .00 1115 DELINQUENT PROPERTY TAX 40,000.00 58,676.05 -18,676.05 146.69 1117 MOTOR VEHICLE TAX 325,000.00 370,181. 77 -45,181. 77 113.90 TOTAL AD VALOREM TAXES 1,790,000.00 1,829,177.18 -39,177.18 102.19 SALES & USE TAXES 1121 UTILITIES TAX 725,000.00 765,605.18 -40,605.18 105.60 TOTAL SALES & USE TAXES 725,000.00 765,605.18 -40,605.18 105.60 PENALTIES & INTEREST ON TAXES 1140 PENALTIES & INTEREST -

Febrero 2005

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: C/ Magdalena nº 10 Cine Doré 28012 Madrid c/ Santa Isabel, 3 Telf.: 91 4672600 28012 Madrid Fax: 91 4672611 Telf.: 91 3691125 (taquilla) 91 369 2118 (gerencia) www.cultura.mcu.es/cine/film/filmoteca.jsp Fax: 91 3691250 MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: 1,35€ por sesión y sala 10,22€ abono de 10 sesiones. Horario de taquilla: 16.15 hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la PROGRAMACIÓN última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. febrero Horario de librería: 2005 16.30 – 22.00 horas. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Horario de cafetería: Menú del día: 14.00 – 16.00 h (excepto domingos) Cafetería: 16.00 h. – 22.30 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico FEBRERO 2005 Chantal Akerman (y II) Peter Watkins Recuerdo de... Carteles de cine 1915-1939. Colección César Fernández Ardavín Gabriel Orozco Hans Werner Henze Muestra de cortometrajes de la Plataforma de Nuevos Realizadores Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su estreno comercial en España figuran en negrita. Los que aparecen en cursiva corresponden a una traducción literal del original o a títulos habitualmente utilizados en español. -

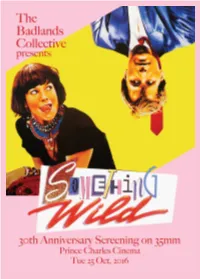

Something-Wild-Programme-Online

USA / 1986 / 114 mins Directed by Jonathan Demme / Produced by Jonathan Demme & Kenneth Utt Written by E. Max Frye / Photographed by Tak Fujimoto / Edited by Craig McKay Music by Laurie Anderson & John Cale / Costume & production design by Norma Moriceau Art Direction by Steve Lineweaver / Casting by Risa Bramon & Billy Hopkins Starring Jeff Daniels (Charlie Driggs), Melanie Griffith (Audrey Hankel, aka ‘Lulu’), Ray Liotta (Ray Sinclair) It’s become pervasive to throw around the label ‘cult classics’ - which often amounts to endlessly celebrating popular hits like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and Aliens for the sake of nostalgia. Meanwhile, we have a kinky little movie like Something Wild, quietly doted on by filmmakers, critics, and underground music lovers, yet the 30th anniversary has almost slipped by unnoticed. Financed by Orion Pictures, and described by its director as “a screwball comedy that turns into a film noir, as life itself does,” it’s a mainstream movie and one of independent spirit, a fun, sexy comedy and a spiky, unnerving thriller, as well as a jamboree of alternative and bohemian talent. Something Wild begins with a traditional meet-cute, as Lulu (Melanie Griffith) catches Charlie (Jeff Daniels) skipping out of a diner without paying for his lunch and confronts him about it. Charlie presents himself as a straight shooter, a rising star at his bank and a stable family man, but Lulu views him as a “closet rebel” and makes it her business to liberate him. The notion of a repressed man being unleashed through a meeting with free spirit recalls Howard Hawks comedies such as Bringing Up Baby or Ball of Fire, but the heroines of those films rarely pursued their prey as aggressively as this. -

FILM CREDITS Last Update: 7/08

KERN COUNTY FILM CREDITS Last Update: 7/08 (TV) Made for Television (D) Documentary (S) Serial TITLE RELEASED LOCATION CAST Keystone Cops unknown Red Rock Canyon The Keystone Cops Opportunity 1913 Taft Fatty Arbuckle Cowboy and the Lady, The 1915 Mojave S. Miller Kent, Hellen Case Back To God's Country 1919 Kern River Valley Nell Shipman, Wheeler Oakman Branded a Bandit 1924 Robbers Roost Yakima Canutt, Alys Murrell King of the Wild Horses, The 1924 Old Kernville Edna Murphy, Charley Chase Man From God's Country, The 1924 Kern River Valley William Fairbanks, Dorothy Revier Greed 1925 Mojave Desert Gibson Gowland, Zasu Pitts White Thunder 1925 Old Kernville Yakima Canutt Wild Horse Canyon 1925 Red Rock Canyon, Kernville Yakima Canutt, Helene Rosson Battling Butler 1926 Bakersfield, Kern River Buster Keaton, Sally O'Neil, Walter James Born to the West 1926 Red Rock Canyon Jack Holt, Margaret Morris Hands Up! 1926 Red Rock Canyon George A Billings, Virginia Lee Corbin Beau Sabreur 1928 Red Rock Canyon Gary Cooper, Evelyn Brent Hell's Heroes 1930 Mojave Desert Charles Bickford, Raymond Hatton Under a Texas Moon 1930 Red Rock Canyon Frank Fay, Myrna Loy Cimarron 1931 Kern River Valley Richard Dix, Irene Dunne Lightning Warrior, The (S) 1931 Old Kernville Rin Tin Tin Phantom of the West, The 1931 Old Kernville Tom Tyler, William Desmond Range Feud 1931 Kernville John Wayne, Buck Jones Vanishing Legion, The 1931 Old Kernville Harry Carey, Edwina Boothe Border Devils 1932 Kern River Valley Harry Carey, Gabby Hayes Flaming Guns 1932 Red Rock Canyon -

Characterization of J. Demme's Hannibal Lecter

International Journal of IJES English Studies UNIVERSITY OF MURCIA http://revistas.um.es/ijes “They don’t have a name for what he is”: The strategic de- characterization of J. Demme’s Hannibal Lecter ENRIQUE CÁMARA-ARENAS* University of Valladolid (Spain) Received: 03/07/2018. Accepted: 05/04/2019. ABSTRACT This essay challenges the myth of Hannibal Lecter, in Demme‟s The Silence of the Lambs, as an enigmatic and unclassifiable character. Lecter‟s enigma is generated through a largely unexplored process of de- characterization, i.e. by recurrently presenting him through the speech of other characters who describe him as unknowable. After considering Lecter‟s case against the background of well-known literary unknowabilities, a deductive phenomenological exploration of Lecter‟s de-characterization is carried out with the assistance of tools from the disciplines of personality and social psychology, and supported by empirical evidence from those fields. The demystifying of Lecter‟s unreadability does not entail a debasement of the film or the character. On the contrary, Lecter‟s de-characterization, albeit a form of narrative manipulation, is viewed as responsible for much of the film‟s impact and success. It produces sensitivity-boosting effects; it mediates the indirect characterization of the other characters; and it engages the spectators‟ self-image thus contributing importantly to the enjoyment and appreciation of the film. KEYWORDS: Hannibal Lecter, psychonarratology, characterization, phenomenology, unknowability, realism. 1. LECTER’S ENIGMA Wrapped in a dirty straitjacket, with his vehement stare and an ominous mouthpiece covering most of his face, Anthony Hopkins‟ version of Hannibal Lecter in Jonathan Demme‟s The _____________________ *Address for correspondence: Plaza del Campus, s/n, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid; e-mail: [email protected] © Servicio de Publicaciones. -

Arizona Filmography

7/20/2004 Arizona Filmography Arizona Film Office 2003 Feature Mona Lisa Smile Columbia Tri-Star / Revolution Films Director Mike Newell Arizona Locations: Parker (Hwy 60 & 72 near Vicksburg) Producer Starring: Julia Roberts, Dirsten Dunst, Julia Stiles Exec. Telefeature Hard Ground LLP (Larry Levinson Productions) Director Frank Dobbs Arizona Locations: Lake Havasu City Producer Starring: Burt Reynolds, Bruce Dern Producer Randy Pope, Lincoln Lageson Exec. Larry Levinson 2002 Feature Charlie's Angels II Columbia Pictures Director Arizona Locations: Page (Glen Canyon Dam, Glen Canyon Bridge) Producer Exec. Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind Mad Chase Productions Studio: Miramax Director George Clooney Arizona Locations: Tucson, Nogales Arizona, Nogales Sonora Mexico Producer Sudzin Starring: George Clooney, Drew Barrymore, Sam Rockwell, Julia Roberts, Brad Pitt Producer Andre Lazar, Steven Reuther, Jeffrey Exec. George Clooney, Stephen Evans (I), Angus Finney Destiny Destiny Productions Studio: Independent Director Katherine Makinney Arizona Locations: Phoenix, Flagstaff Producer Tom Tangen, Mitch Teemley Starring: Jerri Manthey, Stephanie Feury, Todd Cahoon, Tom Tangen, Nancy Stafford Producer Dominic Cianciolo, Michael C. Edwards, Exec. 1 Saguaro Ranch Summer Westpark Productions Director Joey Travolta Arizona Locations: Prescott (Courthouse, Hwy.), Phoenix (Saguaro Lake Guest Ranch) Producer Exec. The Brothel Mt. Parnassus Pictures/Emerging Pictures Studio: Independent Director Amy Waddell Arizona Locations: Jerome, Sedona, Cottonwood Producer Starring: Serena Scott-Thomas, Grace Zabriskie, Whip Hubley, Bruce Payne Producer Amy Waddell, Wade Danielson Exec. The Incredible Hulk Universal Pictures Director Arizona Locations: Page (Lake Powell) Producer Exec. The Reckoning VIG Global Capital, Inc. Director Dustin Rikert Arizona Locations: Tucson (Old Tucson) Producer Starring: Gary Busey Producer Renee Roland Exec. -

Mondo Topless. Dodici Film Di Russ Meyer

COMUNICATO STAMPA Il Museo Nazionale del Cinema presenta al Cinema Massimo Mondo Topless. Dodici film di Russ Meyer 10 – 20 giugno 2011 Cinema Massimo - via Verdi, 18, Torino Il Museo Nazionale del Cinema rende omaggio al cinema di Russ Meyer – regista, sceneggiatore, montatore, direttore della fotografia, attore e produttore cinematografico statunitense – con una retrospettiva dal titolo Mondo Topless. Dodici film di Russ Meyer . L’omaggio a Russ Meyer è un progetto del Museo Nazionale del Cinema. Figlio di un poliziotto e di un’infermiera, Russell Albion Meyer, classe 1922, si accostò alla cinepresa fin da adolescente, e all’età di 14 anni vinse un premio per cineasti dilettanti. Lavorò con la cinepresa anche durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale in Europa, dove filmò, per la US Army Signal Corps della 166° Unità Fotografica, lo sbarco in Normandia e una casa chiusa francese dove conobbe Ernest Hemingway. Dopo il conflitto, tenta a Hollywood la strada di operatore cinematografico, ma rinuncia dopo alcuni mesi perché il sistema hollywoodiano non fa per lui. Trova lavoro come fotografo di riviste patinate per approdare poi a Playboy, dove conoscerà la coniglietta Eve Turner, ex segretaria, per la quale lascerà la prima moglie Betty Valdovinos. Il connubio con Eve è perfetto e lei diventa la fondatrice della Eve Production, casa di finanziamento cinematografico indipendente che finalmente porterà alla luce le pellicole di Russ. Appassionato e ossessionato dalle curve femminili, è stato definito il re dei drive-in. Sesso, violenza e umorismo erano le sue carte vincenti, ma il segreto del suo straordinario successo dipende anche dalle sue procaci attrici: Astrid Lillimor, Babette Bardot, Darla Paris, Sin Lence, Kitten Natividad, Tammy Roché, Tura Satana, Haji, Anouska Hempel e Raven De La Croix. -

The Blues Brothers (Film) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 21/05/2014

The Blues Brothers (film) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 21/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search The Blues Brothers (film) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation The Blues Brothers is a 1980 American musical Technicolor comedy The Blues Brothers Main page film directed by John Landis and starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd Contents as "Joliet" Jake and Elwood Blues, characters developed from "The Featured content Blues Brothers" musical sketch on the NBC variety series Saturday Current events Night Live. Random article Donate to Wikipedia It features musical numbers by rhythm and blues (R&B), soul, and blues Wikimedia Shop singers James Brown, Cab Calloway, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, and Interaction John Lee Hooker. The film is set in and around Chicago, Illinois, and Help features non-musical supporting performances by John Candy, Carrie About Wikipedia Fisher, Charles Napier, and Henry Gibson. Community portal Recent changes The story is a tale of redemption for paroled convict Jake and his Contact page brother Elwood, who take on "a mission from God" to save the Catholic orphanage in which they grew up from foreclosure. To do so, they must Tools What links here reunite their R&B band and organize a performance to earn $5,000 to Related changes pay the tax assessor. Along the way, they are targeted by a destructive Upload file "mystery woman", Neo-Nazis, and a country and western band—all Theatrical release poster Special pages while being relentlessly pursued by the police. Permanent link Directed by John Landis Page information Universal Studios, which had won the bidding war for the film, was Produced by Bernie Brillstein Data item hoping to take advantage of Belushi's popularity in the wake of George Folsey, Jr.