Atti Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bring Together and Discover Unesco About Us

BRING TOGETHER AND DISCOVER UNESCO ABOUT US Mirabilia Network links 17 Chambers of Commerce and as many UNESCO sites. Mirabilia Network is as a project which in 2017 became National Association. Mirabilia Network promotes lesser known destinations, “jewels” and territories bound by UNESCO recognition. Mirabilia Network wants to show different declinations of a territory, between history and culture, tradition and innovation, artistic craftsmanship and gastronomy. Mirabilia Network uses an “interconnected” language to enhance a new cultural tourism and to propose top itineraries without forgetting sustainability. Mirabilia Network develops a network between the Cities, also engaging the Municipal Administrations where our UNESCO sites are. NETWORK ROUTES CHAMBERS OF COMMERCE LINKED FOR THE PROMOTION OF CULTURAL TOURISM SITES IN ITALY MIRABILIA NETWORK BARI BENEVENTO CAMPOBASSO CASERTA CATANIA CROTONE Castel del Monte Complex of Saint Sofia Celebration of Mysteries Caserta Royale Palace Dome Square Ampollino, Sila National Park GENOVA GORIZIA IMPERIA ISERNIA LA SPEZIA MATERA Rolli of Genova Area of Collio Alps of the sea MAB Reserve Collemeluccio - Monterosso Al Mare - Cinque Terre Park of Rupestrian Churches Montedimezzo Alto Molise MESSINA PAVIA PERUGIA POTENZA RAGUSA SAVONA Salina Ponte Coperto Basilica of St. Francesco in Assisi Pollino National Park Val di Noto Beigua National Park SASSARI SIRACUSA TRIESTE UDINE VERONA Mount d’Accoddi Siracusa Dome Unity of Italy Square Patriarcal Basilica of Aquileia City 4 5 Must visit 1 Walk through the historical town of Bari and along the city walls. Your afternoon snack will be the typical focaccia baked in the bakeries located in the narrow alleys of the town. Visit the cathedral, the San Nicola church and the Svevo Castle. -

Discover the Alluring Wines Of

DISCOVER THE ALLURING WINES OF ITAPORTFOLIOLY BOOK l 2015 Leonardo LoCascio Selections For over 35 years, Leonardo LoCascio Selections has represented Italian wines of impeccable quality, character and value. Each wine in the collection tells a unique story about the family and region that produced it. A taste through the portfolio is a journey across Italy’s rich spectrum of geography, history, and culture. Whether a crisp Pinot Bianco from the Dolomites or a rich Aglianico from Campania, the wines of Leonardo LoCascio Selections will transport you to Italy’s outstanding regions. Table of Contents Wines of Northern Italy ............................................................................................ 1-40 Friuli-Venezia-Giulia .................................................................................................. 1-3 Doro Princic ......................................................................................................................................................................2 SUT .......................................................................................................................................................................................3 Lombardia ...................................................................................................................4-7 Barone Pizzini ..................................................................................................................................................................5 La Valle ...............................................................................................................................................................................7 -

Estratto VIII Comm

173 OTTAVA COMMISSIONE COMMISSIONE PER LA MAGISTRATURA ONORARIA ORDINE DEL GIORNO - SPECIALE A INDICE GIUDICI DI PACE .................................................................................................................... 1 COMPONENTI PRIVATI....................................................................................................... 36 ESPERTI DEL TRIBUNALE DI SORVEGLIANZA............................................................. 45 GIUDICI ONORARI DI TRIBUNALE .................................................................................. 48 GIUDICI AUSILIARI DI CORTE DI APPELLO .................................................................. 87 VICE PROCURATORI ONORARI ........................................................................................ 91 TABELLE DI COMPOSIZIONE UFFICI DEL GIUDICE DI PACE.................................... 97 V A R I E.................................................................................................................................. 98 I 174 Odg n. 2190 – speciale A del 3 maggio 2017 La Commissione propone, all’unanimità, l’adozione delle seguenti delibere: GIUDICI DI PACE 1) - 215/GP/2017 - Dott. Salvatore SINDONI, giudice di pace nella sede di NOVARA DI SICILIA (circondario di Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto). Procedura di conferma nell'incarico, per un primo mandato di durata quadriennale, ai sensi degli artt. 1 e 2 del decreto legislativo 31 maggio 2016, n. 92. (relatore Consigliere CLIVIO) Il Consiglio, - vista la domanda di conferma nell'incarico, per -

Wine-Grower-News #283 8-30-14

Wine-Grower-News #283 8-30-14 Midwest Grape & Wine Industry Institute: http://www.extension.iastate.edu/Wine Information in this issue includes: Results of the 6th Annual Cold Climate Competition 8-31, Upper Mississippi Valley Grape Growers Field Day-Baldwin, IA Book Review - THE POWER OF VISUAL STORYTELLING Which States Sell Wine in Grocery Stores - infographic 9-10, Evening Vineyard Walk - Verona, WI 9-(13-14), Principles of Wine Sensory Evaluation – Brainerd, MN 9-27, 5th Annual Loess Hills Wine Festival – Council Bluffs Good Agricultural Practices: Workshops Set for Fall 2014, Spring 2015 10-30 to 11-1, American Wine Society National Conference – Concord, NC Neeto Keeno Show n Tell Videos of Interest Marketing Tidbits Notable Quotables Articles of Interest Calendar of Events th Results of the 6 Annual Cold Climate Competition The 2014 Annual Cold Climate Competition that was held in Minneapolis, MN. The judging involved 284 wines from 59 commercial wineries in 11 states. The 21 expert wine judges awarded 10 Double Gold, 23 Gold, 67 Silver and 80 Bronze medals at this year’s event. Check out the winners here: http://mgga.publishpath.com/Websites/mgga/images/Competition%20Images/2014ICCW CPressRelease_National.pdf Grape Harvest has started in Iowa. Remember to use the Iowa Wine Growers Association “Classifieds” to buy or sell grapes: http://iowawinegrowers.org/category/classifieds/ 1 8-31, Upper Mississippi Valley Grape Growers Field Day - Baldwin, IA When: 1 p.m. - 2:30 pm, Sunday, August 31, 2014 Where: Tabor Home Vineyards & Winery 3570 67th, Street Baldwin, IA 52207 Agenda: This field day covers a vineyard tour, a comparison and evaluation of the NE 2010 cultivars from the University of Minnesota & Cornell University and a chance to sample fresh grapes of the new cultivars and selections. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Evaluation of the Oenological Suitability of Grapes Grown Using Biodynamic Agriculture: the Case of a Bad Vintage R

Journal of Applied Microbiology ISSN 1364-5072 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evaluation of the oenological suitability of grapes grown using biodynamic agriculture: the case of a bad vintage R. Guzzon1, S. Gugole1, R. Zanzotti1, M. Malacarne1, R. Larcher1, C. von Wallbrunn2 and E. Mescalchin1 1 Edmund Mach Foundation, San Michele all’Adige, Italy 2 Institute for Microbiology and Biochemistry, Hochschule Geisenheim University, Geisenheim, Germany Keywords Abstract biodynamic agriculture, FT-IR, grapevine, wine microbiota, yeast. Aims: We compare the evolution of the microbiota of grapes grown following conventional or biodynamic protocols during the final stage of ripening and Correspondence wine fermentation in a year characterized by adverse climatic conditions. Raffaele Guzzon, Edmund Mach Foundation, Methods and Results: The observations were made in a vineyard subdivided Via E. Mach 1, San Michele all’Adige, Italy. into two parts, cultivated using a biodynamic and traditional approach in a E-mail: [email protected] year which saw a combination of adverse events in terms of weather, creating 2015/1999: received 11 June 2015, revised the conditions for extensive proliferation of vine pests. The biodynamic 12 November 2015 and accepted approach was severely tested, as agrochemicals were not used and vine pests were 14 November 2015 counteracted with moderate use of copper, sulphur and plant extracts and with intensive use of agronomical practices aimed at improving the health of the doi:10.1111/jam.13004 vines. Agronomic, microbiological and chemical testing showed that the response of the vineyard cultivated using a biodynamic approach was comparable or better to that of vines cultivated using the conventional method. -

Phenolic Compounds As Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity

foods Review Phenolic Compounds as Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity Vakare˙ Merkyte˙ 1,2 , Edoardo Longo 1,2,* , Giulia Windisch 1,2 and Emanuele Boselli 1,2 1 Faculty of Science and Technology, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Piazza Università 5, 39100 Bozen-Bolzano, Italy; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (G.W.); [email protected] (E.B.) 2 Oenolab, NOI Techpark South Tyrol, Via A. Volta 13B, 39100 Bozen-Bolzano, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0471-017691 Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 28 November 2020; Published: 1 December 2020 Abstract: Targeted and untargeted determinations are being currently applied to different classes of natural phenolics to develop an integrated approach aimed at ensuring compliance to regulatory prescriptions related to specific quality parameters of wine production. The regulations are particularly severe for wine and include various aspects of the viticulture practices and winemaking techniques. Nevertheless, the use of phenolic profiles for quality control is still fragmented and incomplete, even if they are a promising tool for quality evaluation. Only a few methods have been already validated and widely applied, and an integrated approach is in fact still missing because of the complex dependence of the chemical profile of wine on many viticultural and enological factors, which have not been clarified yet. For example, there is a lack of studies about the phenolic composition in relation to the wine authenticity of white and especially rosé wines. This review is a bibliographic account on the approaches based on phenolic species that have been developed for the evaluation of wine quality and frauds, from the grape varieties (of V. -

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are Hybrid Varieties Right for Oklahoma?

Matching Grape Varieties to Sites Are hybrid varieties right for Oklahoma? Bruce Bordelon Purdue University Wine Grape Team 2014 Oklahoma Grape Growers Workshop 2006 survey of grape varieties in Oklahoma: Vinifera 80%. Hybrids 15% American 7% Muscadines 1% Profiles and Challenges…continued… • V. vinifera cultivars are the most widely grown in Oklahoma…; however, observation and research has shown most European cultivars to be highly susceptible to cold damage. • More research needs to be conducted to elicit where European cultivars will do best in Oklahoma. • French-American hybrids are good alternatives due to their better cold tolerance, but have not been embraced by Oklahoma grape growers... Reasons for this bias likely include hybrid cultivars being perceived as lower quality than European cultivars, lack of knowledge of available hybrid cultivars, personal preference, and misinformation. Profiles and Challenges…continued… • The unpredictable continental climate of Oklahoma is one of the foremost obstacles for potential grape growers. • It is essential that appropriate site selection be done prior to planting. • Many locations in Oklahoma are unsuitable for most grapes, including hybrids and American grapes. • Growing grapes in Oklahoma is a risky endeavor and minimization of potential loss by consideration of cultivar and environmental interactions is paramount to ensure long-term success. • There are areas where some European cultivars may succeed. • Many hybrid and American grapes are better suited for most areas of Oklahoma than -

Untersuchung Der Transkriptionellen Regulation Von Kandidatengenen Der Pathogenabwehr Gegen Plasmopara Viticola in Der Weinrebe

Tina Moser Institut für Rebenzüchtung Untersuchung der transkriptionellen Regulation von Kandidatengenen der Pathogenabwehr gegen Plasmopara viticola in der Weinrebe Dissertationen aus dem Julius Kühn-Institut Julius Kühn-Institut Bundesforschungsinstitut für Kulturpfl anzen Kontakt/Contact: Tina Moser Arndtstraße 6 67434 Neustadt Die Schriftenreihe ,,Dissertationen aus dem Julius Kühn-lnstitut" veröffentlicht Doktorarbeiten, die in enger Zusammenarbeit mit Universitäten an lnstituten des Julius Kühn-lnstituts entstanden sind The publication series „Dissertationen aus dem Julius Kühn-lnstitut" publishes doctoral dissertations originating from research doctorates completed at the Julius Kühn-Institut (JKI) either in close collaboration with universities or as an outstanding independent work in the JKI research fields. Der Vertrieb dieser Monographien erfolgt über den Buchhandel (Nachweis im Verzeichnis lieferbarer Bücher - VLB) und OPEN ACCESS im lnternetangebot www.jki.bund.de Bereich Veröffentlichungen. The monographs are distributed through the book trade (listed in German Books in Print - VLB) and OPEN ACCESS through the JKI website www.jki.bund.de (see Publications) Wir unterstützen den offenen Zugang zu wissenschaftlichem Wissen. Die Dissertationen aus dem Julius Kühn-lnstitut erscheinen daher OPEN ACCESS. Alle Ausgaben stehen kostenfrei im lnternet zur Verfügung: http://www.jki.bund.de Bereich Veröffentlichungen We advocate open access to scientific knowledge. Dissertations from the Julius Kühn-lnstitut are therefore published open -

Azienda Agricola Possa Cinque Terre Bianco

Artisanal Cellars artisanalcellars.com [email protected] Azienda Agricola Possa Cinque Terre Bianco Winery: Azienda Agricola Possa Category: Wine – Still – White Grape Variety: Bosco, Rossese bianco, Albarola, Picabon, Frapelao Region: Riomaggiore, Cinque Terre/ Liguria/ Italy Vineyard: located in the municipality of Riomaggiore Winery established: 2004 Feature: Biodynamic Product Information Soil: Schist, rocky and sandstone remains Elevation: up to 122 meters (400 feet), South-East exposure Age of vines: 40+ years old Vinification: Earlier harvest than tradition, to enjoy a higher acidity. Hand-harvest. Vinification: destemming, fermentation for 4 days with the skins, then it is separated from the skins and left in steel for another 4 days, after the upper part of the barrel continues to ferment in steel, while the lower part is put into barrels. Aging in oak and acacia barriques. Yield: 35 HL/ hectare Tasting Note: The varieties used are unique to Cinque Terre and almost unknown elsewhere. Golden yellow color. Nose and taste of Mediterranean shrubs, very aromatic with mineral aromas. A wine that has a history of more than 2,000 years that unlike the sciacchetrà has not had the same publicity over the centuries but that especially in the last 20 years is returning to the fore thanks to its uniqueness. Production: 5,000 to 8,000 bottles Alc: 13.5% vol. Producer Information To visit Possa, Heydi Bonnanini’s vineyards in Riomaggiore, is a breathtaking experience for the senses: the shocking beauty of Cinque Terre terraces on cliff sides so steep that they seem to fall straight into the sea, the ingenious monorail car that is required to access the vines, prickly pear cacti towering above the narrow track. -

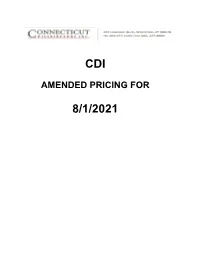

Cdi 8/1/2021

- CDI AMENDED PRICING FOR 8/1/2021 Amended Prices for the Month of August 2021 Name of Licensee: Date:07/15/2021 Initial Filing Amending To Notes1 Item # Item Bottle Case Resale Bott PO Case PO Amending To Bottle Case Resale Bott PO Case PO 9024256 ABSOLUT VDK 80 24B 200ML 7.21 331.68 9.29 18.24 18.24 HARTLEY & PARKER 6.99 331.68 9.29 28.80 18.24 9024273 ABSOLUT VDK CITRON 24B 200ML 7.21 331.68 9.29 18.24 18.24 HARTLEY & PARKER 6.99 331.68 9.29 28.80 18.24 9365820 ABSOLUT VDK JUICE APL 70 6B 750ML 15.99 190.80 25.99 60.00 60.00 HARTLEY & PARKER 15.98 190.80 26.69 60.00 60.00 9417204 ABSOLUT VDK JUICE PEAR ELD 70 6B 750ML 15.99 190.80 25.99 60.00 60.00 HARTLEY & PARKER 15.98 190.80 26.99 60.00 60.00 9024282 ABSOLUT VDK MANDRIN 24B 200ML 7.21 331.68 9.29 18.24 18.24 HARTLEY & PARKER 6.99 331.68 9.29 28.80 18.24 9006515 ANTIOQUEN O AGUARDIEN TE 375ML 9.49 225.84 11.99 BARTON BRESCOME 7.59 179.34 9.89 9.60 9.60 9006514 ANTIOQUEN O AGUARDIEN TE 750ML 17.49 166.92 22.99 HARTLEY & PARKER 15.99 190.92 22.99 24.00 24.00 9006513 ANTIOQUENO AGUARDIENTE 1L Ammended manually HARTLEY & PARKER 17.99 190.92 26.99 42.00 66.00 keep our case 9448162 BACARDI RUM GLD 24B 200ML 4.10 176.77 5.99 23.66 23.66 BARTON BRESCOME 4.09 176.77 5.99 23.66 23.66 40261 BACARDI RUM GLD 375ML 6.09 138.06 7.99 25.10 25.10 EDER BROTHERS 6.06 138.06 7.99 25.10 25.10 41178 BACARDI RUM LIMON 24B 200ML 4.10 176.77 6.49 23.66 23.66 BARTON BRESCOME 4.09 176.77 5.99 23.66 23.66 9448163 BACARDI RUM SUPERIOR 24B 200ML 4.10 176.77 5.99 23.66 23.66 BARTON BRESCOME 4.09 176.77 5.99 23.66 23.66 40162 BACARDI RUM SUPERIOR FLK 375ML 6.09 138.06 7.99 25.10 25.10 EDER BROTHERS 6.06 138.06 7.99 25.10 25.10 153445 BALLANTINE S SCOTCH FINEST 750ML 19.30 229.15 24.39 ALLAN S. -

Chemical Characteristics of Wine Made by Disease Tolerant Varieties

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI UDINE in agreement with FONDAZIONE EDMUND MACH PhD School in Agricultural Science and Biotechnology Cycle XXX Doctoral Thesis Chemical characteristics of wine made by disease tolerant varieties PhD Candidate Supervisor Silvia Ruocco Dr. Urska Vrhovsek Co-Supervisor Prof. Doris Rauhut DEFENCE YEAR 2018 To the best gift that life gave us: to you Nonna Rosa CONTENTS Abstract 1 Aim of the PhD project 2 Chapter 1 Introduction 3 Preface to Chapter 2 17 Chapter 2 The metabolomic profile of red non-V. vinifera genotypes 19 Preface to Chapter 3 and 4 50 Chapter 3 Study of the composition of grape from disease tolerant varieties 56 Chapter 4 Investigation of volatile and non-volatile compounds of wine 79 produced by disease tolerant varieties Concluding remarks 140 Summary of PhD experiences 141 Acknowledgements 142 Abstract Vitis vinifera L. is the most widely cultivated Vitis species around the world which includes a great number of cultivars. Owing to the superior quality of their grapes, these cultivars were long considered the only suitable for the production of high quality wines. However, the lack of resistance genes to fungal diseases like powdery and downy mildew (Uncinula necator and Plasmopara viticola) makes it necessary the application of huge amounts of chemical products in vineyard. Thus, the search for alternative and more sustainable methods to control the major grapevine pathogens have increased the interest in new disease tolerant varieties. Chemical characterisation of these varieties is an important prerequisite to evaluate and promote their use on the global wine market. The aim of this project was to produce a comprehensive study of some promising new disease tolerant varieties recently introduced to the cultivation by identifying the peculiar aspects of their composition and measuring their positive and negative quality traits.