Class 3: Grandest of the Grand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meyerbeer Was One of the Most Significant Opera Composers of All Time

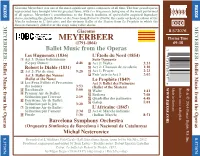

NAXOS NAXOS Giacomo Meyerbeer was one of the most significant opera composers of all time. The four grand operas represented here brought him his greatest fame, with Les Huguenots being one of the most performed of all operas. Meyerbeer’s contributions to the French tradition of opéra-ballet acquired legendary status, including the ghostly Ballet of the Nuns from Robert le Diable; the exotic orchestral colour of the Marche indienne in L’Africaine; and the virtuoso Ballet of the Skaters from Le Prophète in which the dancers famously glided over the stage using roller skates. DDD MEYERBEER: MEYERBEER: Giacomo 8.573076 MEYERBEER Playing Time (1791-1864) 69:38 Ballet Music from the Operas 7 Les Huguenots (1836) L’Étoile du Nord (1854) 47313 30767 1 Act 3: Danse bohémienne Suite Dansante Ballet Music from the Operas Ballet Music from (Gypsy Dance) 4:46 9 Act 2: Waltz 3:32 the Operas Ballet Music from Robert le Diable (1831) 0 Act 2: Chanson de cavalerie 1:18 2 Act 2: Pas de cinq 9:28 ! Act 1: Prayer 2:23 Act 3: Ballet des Nonnes @ Entr’acte to Act 3 2:02 (Ballet of the Nuns) Le Prophète (1849) 3 Les Feux Follets et Procession Act 3: Ballet des Patineurs 8 des nonnes 3:53 (Ballet of the Skaters) www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 4 Bacchanale 5:00 # Waltz 1:41 & 5 Premier Air de Ballet: $ Redowa 7:08 Ꭿ Séduction par l’ivresse 2:19 % Quadrilles des patineurs 4:48 6 Deuxième Air de Ballet: 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert Le Diable Online

cXKt6 [Get free] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Online [cXKt6.ebook] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Pdf Free Richard Arsenty ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4398313 in Books 2009-03-01Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .50 x 5.70l, .52 #File Name: 1847189644180 pages | File size: 19.Mb Richard Arsenty : The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Liobretto for Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable"By radamesAn excellent publication which contained many stage directions not always reproduced in the nineteenth-century vocal scores and a fine translation. Useful at a time of renewed interest in this opera at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most important and influential opera composers of the nineteenth century, enjoyed a fame during his lifetime hardly rivaled by any of his contemporaries. This eleven volume set provides in one collection all the operatic texts set by Meyerbeer in his career. The texts offer the most complete versions available. Each libretto is translated into modern English by Richard Arsenty; and each work is introduced by Robert Letellier. In this comprehensive edition of Meyerbeer's libretti, the original text and its translation are placed on facing pages for ease of use. About the AuthorRichard Arsenty, a native of the U.S. -

The Great William Tell, a Girl Who Is Magic at Maths and a TIGER with NO MANNERS!

ORIES! FANTASTIC NEW ST TM Storytime OPERATION UNICORN A mythical being in disguise! BALOO'S BATH DAY Mowgli bathes a big bear! TheTHE Great William GRIFFIN Tell, a Girl Who is Magic at Maths and a TIGER WITH NO MANNERS! ver cle ! ll of ricks ies fu o0l t stor and c characters Check out the fantastic adventures of a smart smith, a girl genius, a wise monk and a clever farmboy! This issue belongs to: SPOT IT! “Don’t worry, you silly bear – I will get you clean!” Storytime™ magazine is published every month by ILLUSTRATORS: Storytime, 90 London Rd, London, SE1 6LN. Luján Fernández Operation Unicorn Baloo’s Bath Day © Storytime Magazine Ltd, 2020. All rights reserved. Giorgia Broseghini No part of this magazine may be used or reproduced Caio Bucaretchi William Tell without prior written permission of the publisher. Flavia Sorrentino The Enchantress of Number Printed by Warners Group. Ekaterina Savic The Griffin Wiliam Luong The Unmannerly Tiger Creative Director: Lulu Skantze L Schlissel The Magic Mouthful Editor: Sven Wilson Nicolas Maia The Blacksmith Commercial Director: Leslie Coathup and the Iron Man Storytime and its paper suppliers have been independently certified in accordance with the rules of the FSC® (Forest Stewardship Council)®. With stories from Portugal, Switzerland, Korea and Uganda! This magazine is magical! Read happily ever after... Tales from Today Famous Fables Operation Unicorn The Unmannerly Tiger When Matilda spots a mythical Can you trust a hungry tiger? being in her garden, she comes A Korean monk finds out when up with a plan to help it get home! 6 he lets one out of a trap! 32 Short Stories, Big Dreams Storyteller’s Corner Baloo’s Bath Day The Magic Mouthful When Baloo has a honey-related Maria learns how to stop accident, Mowgli gives his big arguments – with just a bear friend a bath! 12 mouthful of water! 36 Myths and Legends Around the World Tales William Tell The blacksmith A Swiss bowman shows off and the Iron Man his skill and puts a wicked A king asks a blacksmith governor in his place! 14 to do the impossible.. -

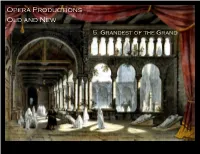

Opera Productions Old and New

Opera Productions Old and New 5. Grandest of the Grand Grand Opera Essentially a French phenomenon of the 1830s through 1850s, although many of its composers were foreign. Large-scale works in five acts (sometimes four), calling for many scene-changes and much theatrical spectacle. Subjects taken from history or historical myth, involving clear moral choices. Highly demanding vocal roles, requiring large ranges, agility, stamina, and power. Orchestra more than accompaniment, painting the scene, or commenting. Substantial use of the chorus, who typically open or close each act. Extended ballet sequences, in the second or third acts. Robert le diable at the Opéra Giacomo Meyerbeer (Jacob Liebmann Beer, 1791–1864) Germany, 1791 Italy, 1816 Paris, 1825 Grand Operas for PAris 1831, Robert le diable 1836, Les Huguenots 1849, Le prophète 1865, L’Africaine Premiere of Le prophète, 1849 The Characters in Robert le Diable ROBERT (tenor), Duke of Normandy, supposedly the offspring of his mother’s liaison with a demon. BERTRAM (bass), Robert’s mentor and friend, but actually his father, in thrall to the Devil. ISABELLE (coloratura soprano), Princess of Sicily, in love with Robert, though committed to marry the winner of an upcoming tournament. ALICE (lyric soprano), Robert’s foster-sister, the moral reference-point of the opera. Courbet: Louis Guéymard as Robert le diable Robert le diable, original design for Act One Robert le diable, Act One (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act Two (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act -

16 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert Le Diable, 1831. the Nuns' Ballet. Meyerbeer's Synesthetic Cocktail Debuts at the Paris Opera

Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert le diable, 1831. The nuns’ ballet. Meyerbeer’s synesthetic cocktail debuts at the Paris Opera. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 16 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 The Prophet and the Pendulum: Sensational Science and Audiovisual Phantasmagoria around 1848 JOHN TRESCH Nothing is more wonderful, nothing more fantastic than actual life. —E.T.A. Hoffmann, “The Sand-Man” (1816) The Fantastic and the Positive During the French Second Republic—the volatile period between the 1848 Revolution and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état—two striking per - formances fired the imaginations of Parisian audiences. The first, in 1849, was a return: after more than a decade, the master of the Parisian grand opera, Giacomo Meyerbeer, launched Le prophète , whose complex instrumentation and astound - ing visuals—including the unprecedented use of electric lighting—surpassed even his own previous innovations in sound and vision. The second, in 1851, was a debut: the installation of Foucault’s pendulum in the Panthéon. The installation marked the first public exposure of one of the most celebrated demonstrations in the history of science. A heavy copper ball suspended from the former cathedral’s copula, once set in motion, swung in a plane that slowly traced a circle on the marble floor, demonstrating the rotation of the earth. In terms of their aim and meaning, these performances might seem polar opposites. -

![ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1791/robert-le-diable-music-by-giacomo-meyerbeer-libretto-by-eug%C3%A8ne-scribe-germain-delavigne-first-performance-op%C3%A9ra-acad%C3%A9mie-royale-paris-november-21-1831-1191791.webp)

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie royale], Paris, November 21, 1831 Robert, son of Bertha, daughter of the Duke of Normandy (who has been seduced by the Devil), wanders to Palermo in Sicily, where he falls in love with the King's daughter, Isabella, and intends to joust in a tournament to win her. His companion, Bertram (in reality his satanic father), forestalls him at every juncture. A compatriot, the minstrel Raimbaut, warns the company about Robert the Devil, and is about to be hanged when Robert's foster sister Alice appears to save him. She has followed Robert with a message from his dead mother; Robert confides to her his love for Isabella, who has banished him because of his jealousy. Alice promises to help and asks in return that she be allowed to marry Raimbaut. When Bertram enters, she recognizes him and hides. Bertram induces Robert to gamble away all his substance. Alice intercedes for Robert with Isabella, who presents him with a new suit of armor to fight the Prince of Granada, but Bertram lures him away from combat, and the Prince wins Isabella. In the cavern of St. Irene, Raimbaut waits for Alice but is tempted by Bertram with money, which he leaves to spend. Alice enters on a scene which betrays Bertram as an unholy spirit, and in spite of clinging to her cross, is about to be destroyed by Bertram when Robert enters. The young man is desperate and ready to resort to magic arts. -

Die Eidgenossen Als Lykier Bachofens Mutterrecht Und Schillers Wilhelm Tell

Dtsch Vierteljahrsschr Literaturwiss Geistesgesch (2020) 94:347–383 https://doi.org/10.1007/s41245-020-00111-5 BEITRAG Die Eidgenossen als Lykier Bachofens Mutterrecht und Schillers Wilhelm Tell Yahya Elsaghe Online publiziert: 19. August 2020 © Der/die Autor(en) 2020 Zusammenfassung Wie verhielt sich Johann Jakob Bachofen, der unablässig den Wahrheitsgehalt klassischer oder auch wildfremder Mythen zu rehabilitieren ver- suchte, zur Gründungssage seines eigenen Lands? Wie zu den immer lauter gewor- denen Zweifeln an ihrem Sachgehalt? Und sieht man seinem Hauptwerk an, dass es einer geschrieben hat, der zumal von ihrer Schiller’schen Aufbereitung geprägt sein musste? Oder in welcher Beziehung steht seine Theorie vom einstigen Mutterrecht des antiken Kulturraums zu den Vorstellungen, die Schiller sich und der Nachwelt von den alten Schweizern und Schweizerinnen machte? Die notgedrungen nur noch spekulative Antwort auf diese letzte Frage wirft immerhin ein Licht auf die Ge- schlechterverhältnisse in Schillers Wilhelm Tell und dessen wichtigster Quelle, die auch Bachofen nachweislich bekannt war. The Swiss as Lycians Bachofen’s Mother Right and Schiller’s William Tell Abstract How did Johann Jakob Bachofen, who constantly tried to rehabilitate the truth of classical or even entirely alien myths, react to the legend of his own coun- try’s founding and to the ever growing doubts about its substance? And does one see in his main work that it was written by someone who must have been influenced by Schiller’s treatment of this legend? Or how does his theory of the former mother right of the ancient cultural realm relate to the ideas that Schiller developed for himself and posterity about the old Switzerland’s brothers – and sisters? The necessarily only speculative answer to this last question nevertheless sheds light on the gender re- lations in Schiller’s William Tell and his most important source, which demonstra- bly was also known to Bachofen. -

Jonathan Huff MAR Thesis

Durham E-Theses La musique des lumières: The Enlightenment Origins of French Revolutionary Music, 1789-1799 HUFF, JONATHAN,EDWARD How to cite: HUFF, JONATHAN,EDWARD (2015) La musique des lumières: The Enlightenment Origins of French Revolutionary Music, 1789-1799 , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11021/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 1 2 For my parents, Martin and Julie Huff 3 4 ABSTRACT It is commonly believed that the music of the French Revolution (1789-1799) represented an unusual rupture in compositional praxis. Suddenly patriotic hymns, chansons , operas and instrumental works overthrew the supremacy of music merely for entertainment as the staple of musical life in France. It is the contention of this thesis that this ‘rupture’ had in fact been a long time developing, and that the germ of this process was sown in the philosophie of the previous decades. -

16 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert Le Diable, 1831. the Nuns' Ballet

Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert le diable, 1831. The nuns’ ballet. Meyerbeer’s synesthetic cocktail debuts at the Paris Opera. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 16 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00030 by guest on 25 September 2021 The Prophet and the Pendulum: Sensational Science and Audiovisual Phantasmagoria around 1848 JOHN TRESCH Nothing is more wonderful, nothing more fantastic than actual life. —E.T.A. Hoffmann, “The Sand-Man” (1816) The Fantastic and the Positive During the French Second Republic—the volatile period between the 1848 Revolution and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état—two striking per - formances fired the imaginations of Parisian audiences. The first, in 1849, was a return: after more than a decade, the master of the Parisian grand opera, Giacomo Meyerbeer, launched Le prophète , whose complex instrumentation and astound - ing visuals—including the unprecedented use of electric lighting—surpassed even his own previous innovations in sound and vision. The second, in 1851, was a debut: the installation of Foucault’s pendulum in the Panthéon. The installation marked the first public exposure of one of the most celebrated demonstrations in the history of science. A heavy copper ball suspended from the former cathedral’s copula, once set in motion, swung in a plane that slowly traced a circle on the marble floor, demonstrating the rotation of the earth. In terms of their aim and meaning, these performances might seem polar opposites. Opera aficionados have seen Le prophète as the nadir of midcentury bad taste, demanding correction by an idealist conception of music. Grand opera in its entirety has been seen as mass-produced phantasmagoria, mechani - cally produced illusion presaging the commercial deceptions of the society of the spectacle. -

Bee Round 2 Bee Round 2 Regulation Questions

NHBB B-Set Bee 2016-2017 Bee Round 2 Bee Round 2 Regulation Questions (1) As a state representative, this man sponsored the anti-contraception law that was overturned a century later in Griswold v. Connecticut. This man built two mansions in Bridgeport and patronized the U.S. tour of the \Swedish Nightingale," opera singer Jenny Lind. This business partner of James Bailey died three decades before his company was merged with that of the Ringling Brothers. For the point, name this 19th century entrepreneur whose \Greatest Show on Earth" became America's largest circus. ANSWER: Phineas Taylor \P.T." Barnum (2) Troops were parachuted into this battle during Operation Castor. The outposts Beatrice and Gabrielle were captured during this battle, in which Charles Piroth committed suicide by hand grenade after failing to destroy the camouflaged artillery of Vo Nguyen Giap. This battle led to the signing of the Geneva Accords, in which one side agreed to withdraw from Indochina. For the point, name this 1953 victory for the Viet Minh in their struggle for independence from France. ANSWER: Battle of Dien Bien Phu (3) Fighting in this war included the shelling of dockyards at Sveaborg. This conflict escalated when one side claimed the right to protect holy places in Palestine, and its immediate cause was the destruction of an Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Sinope [sin-oh-pee]. The Thin Red Line participated in the Battle of Balaclava, part of the effort to besiege Sevastopol during this war. The Light Brigade charged in, for the point, what 1850s war between Russia and a Franco-British alliance on a Black Sea peninsula? ANSWER: Crimean War (4) For his failure to warn the United States about this event, Michael Fortier was sentenced to twelve years in prison in 1998. -

Wilhelm Tell 1789 — 1895

THE RE-APPROPRIATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF A NATIONAL SYMBOL: WILHELM TELL 1789 — 1895 by RETO TSCHAN B.A., The University of Toronto, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2000 © Reto Tschan, 2000. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the library shall make it freely available for reference and study. 1 further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of 'HvS.'hK^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date l^.+. 2000. 11 Abstract Wilhelm Tell, the rugged mountain peasant armed with his crossbow, is the quintessential symbol of Switzerland. He personifies both Switzerland's ancient liberty and the concept of an armed Swiss citizenry. His likeness is everywhere in modern Switzerland and his symbolic value is clearly understood: patriotism, independence, self-defense. Tell's status as the preeminent national symbol of Switzerland is, however, relatively new. While enlightened reformers of the eighteenth century cultivated the image of Tell for patriotic purposes, it was, in fact, during the French occupation of Switzerland that Wilhelm Tell emerged as a national symbol. -

Stephanie Schroedter Listening in Motion and Listening to Motion. the Concept of Kinaesthetic Listening Exemplified by Dance Compositions of the Meyerbeer Era

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Berner Fachhochschule: ARBOR Stephanie Schroedter Listening in Motion and Listening to Motion. The Concept of Kinaesthetic Listening Exemplified by Dance Compositions of the Meyerbeer Era Musical life in Paris underwent profound and diverse changes between the July Monar- chy and the Second Empire. One reason for this was the availability of printed scores for a broader public as an essential medium for the distribution of music before the advent of mechanical recordings. Additionally, the booming leisure industry encouraged music commercialization, with concert-bals and café-concerts, the precursors of the variétés, blurring the boundaries between dance and theatre performances. Therefore there was not just one homogeneous urban music culture, but rather a number of different music, and listening cultures, each within a specific urban setting. From this extensive field I will take a closer look at the music of popular dance or, more generally, movement cultures. This music spanned the breadth of cultural spaces, ranging from magnificent ballrooms – providing the recognition important to the upper-classes – to relatively modest dance cafés for those who enjoyed physical exercise above social distinction. Concert halls and musical salons provided a venue for private audiences who preferred themoresedateactivityoflisteningtostylized dance music rather than dancing. Café- concerts and popular concert events offered diverse and spectacular entertainment