Two Operas for One Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meyerbeer Was One of the Most Significant Opera Composers of All Time

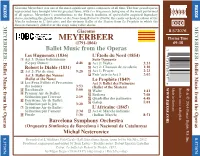

NAXOS NAXOS Giacomo Meyerbeer was one of the most significant opera composers of all time. The four grand operas represented here brought him his greatest fame, with Les Huguenots being one of the most performed of all operas. Meyerbeer’s contributions to the French tradition of opéra-ballet acquired legendary status, including the ghostly Ballet of the Nuns from Robert le Diable; the exotic orchestral colour of the Marche indienne in L’Africaine; and the virtuoso Ballet of the Skaters from Le Prophète in which the dancers famously glided over the stage using roller skates. DDD MEYERBEER: MEYERBEER: Giacomo 8.573076 MEYERBEER Playing Time (1791-1864) 69:38 Ballet Music from the Operas 7 Les Huguenots (1836) L’Étoile du Nord (1854) 47313 30767 1 Act 3: Danse bohémienne Suite Dansante Ballet Music from the Operas Ballet Music from (Gypsy Dance) 4:46 9 Act 2: Waltz 3:32 the Operas Ballet Music from Robert le Diable (1831) 0 Act 2: Chanson de cavalerie 1:18 2 Act 2: Pas de cinq 9:28 ! Act 1: Prayer 2:23 Act 3: Ballet des Nonnes @ Entr’acte to Act 3 2:02 (Ballet of the Nuns) Le Prophète (1849) 3 Les Feux Follets et Procession Act 3: Ballet des Patineurs 8 des nonnes 3:53 (Ballet of the Skaters) www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 4 Bacchanale 5:00 # Waltz 1:41 & 5 Premier Air de Ballet: $ Redowa 7:08 Ꭿ Séduction par l’ivresse 2:19 % Quadrilles des patineurs 4:48 6 Deuxième Air de Ballet: 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France the Politics of Halevy’S´ La Juive

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France The Politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive Diana R. Hallman published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Diana R. Hallman 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Dante MT 10.75/14 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Hallman, Diana R. Opera, liberalism, and antisemitism in nineteenth-century France: the politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive / by Diana R. Hallman. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in opera) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65086 0 1. Halevy,´ F., 1799–1862. Juive. 2. Opera – France – 19th century. 3. Antisemitism – France – History – 19th century. 4. Liberalism – France – History – 19th century. i. Title. ii. Series. ml410.h17 h35 2002 782.1 –dc21 2001052446 isbn 0 521 65086 0 -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert Le Diable Online

cXKt6 [Get free] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Online [cXKt6.ebook] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Pdf Free Richard Arsenty ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4398313 in Books 2009-03-01Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .50 x 5.70l, .52 #File Name: 1847189644180 pages | File size: 19.Mb Richard Arsenty : The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Liobretto for Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable"By radamesAn excellent publication which contained many stage directions not always reproduced in the nineteenth-century vocal scores and a fine translation. Useful at a time of renewed interest in this opera at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most important and influential opera composers of the nineteenth century, enjoyed a fame during his lifetime hardly rivaled by any of his contemporaries. This eleven volume set provides in one collection all the operatic texts set by Meyerbeer in his career. The texts offer the most complete versions available. Each libretto is translated into modern English by Richard Arsenty; and each work is introduced by Robert Letellier. In this comprehensive edition of Meyerbeer's libretti, the original text and its translation are placed on facing pages for ease of use. About the AuthorRichard Arsenty, a native of the U.S. -

L'autorité, 5 Octobre 1895, Pp

JOURNAL DES JEUNES PERSONNES, mai 1862, pp. 195–198. Notre directrice veut, mesdemoiselles, que je vous dise quelques mots du célèbre musicien que la France vient de perdre. La chose n’est pas aisée, et notre directrice le sait bien, car il s’agit de faire un choix entre des œuvres, des faits et des aventures qui se rapportent à une carrière presqu’entièrement consacrée au théâtre. Mais on peut se borner à vous faire apprécier Halévy comme compositeur, comme homme et comme secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts. C’est ce que je vais essayer de faire; je ne dirai que l’essentiel. Heureux si, grâce à mon sujet, je parviens à vous intéresser! Jacques François-Fromental-Élie Halévy naquit à Paris, le 27 mai 1799, d’une famille israélite, et donna de bonne heure des marques d’une intelligence précoce. Il n’avait pas encore atteint l’âge de dix ans qu’il entra, le 30 janvier 1809, au Conservatoire, dans la classe de solfége de M. Cazot. L’année suivante, il eut pour maître de piano M. Charles Lambert. En 1811, il prit des leçons d’harmonie de Berton; après quoi il travailla pendant cinq ans le contre-point sous la direction de Cherubini, dont il devint l’élève de prédilection. Après dix années d’études musicales assidues et persévérantes, Halévy concourut pour le grand prix de Rome; ce fut à sa cantate d’Herminie qu’il dut le titre de lauréat. Toutefois, il ne partit pas immédiatement pour l’Italie. Il resta à Paris pour mettre en musique le texte hébreu du psaume De profundis, destiné à être chanté dans les synagogues à l’occasion de la mort du duc de Berry, et pour écrire la partition d’un grand opéra intitulé les Bohémiennes qui ne fut point représenté. -

Opera Productions Old and New

Opera Productions Old and New 5. Grandest of the Grand Grand Opera Essentially a French phenomenon of the 1830s through 1850s, although many of its composers were foreign. Large-scale works in five acts (sometimes four), calling for many scene-changes and much theatrical spectacle. Subjects taken from history or historical myth, involving clear moral choices. Highly demanding vocal roles, requiring large ranges, agility, stamina, and power. Orchestra more than accompaniment, painting the scene, or commenting. Substantial use of the chorus, who typically open or close each act. Extended ballet sequences, in the second or third acts. Robert le diable at the Opéra Giacomo Meyerbeer (Jacob Liebmann Beer, 1791–1864) Germany, 1791 Italy, 1816 Paris, 1825 Grand Operas for PAris 1831, Robert le diable 1836, Les Huguenots 1849, Le prophète 1865, L’Africaine Premiere of Le prophète, 1849 The Characters in Robert le Diable ROBERT (tenor), Duke of Normandy, supposedly the offspring of his mother’s liaison with a demon. BERTRAM (bass), Robert’s mentor and friend, but actually his father, in thrall to the Devil. ISABELLE (coloratura soprano), Princess of Sicily, in love with Robert, though committed to marry the winner of an upcoming tournament. ALICE (lyric soprano), Robert’s foster-sister, the moral reference-point of the opera. Courbet: Louis Guéymard as Robert le diable Robert le diable, original design for Act One Robert le diable, Act One (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act Two (Chantal Thomas, designer) Robert le diable, Act -

122 a Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. Music Is As Old As The

122 A Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. A CENTURY OF GRAND OPERA IN PHILADELPHIA. A Historical Summary read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Monday Evening, January 12, 1920. BY JOHN CURTIS. Music is as old as the world itself; the Drama dates from before the Christian era. Combined in the form of Grand Opera as we know it today they delighted the Florentines in the sixteenth century, when Peri gave "Dafne" to the world, although the ancient Greeks listened to great choruses as incidents of their comedies and tragedies. Started by Peri, opera gradually found its way to France, Germany, and through Europe. It was the last form of entertainment to cross the At- lantic to the new world, and while some works of the great old-time composers were heard in New York, Charleston and New Orleans in the eighteenth century, Philadelphia did not experience the pleasure until 1818 was drawing to a close, and so this city rounded out its first century of Grand Opera a little more than a year ago. But it was a century full of interest and incident. In those hundred years Philadelphia heard 276 different Grand Operas. Thirty of these were first heard in America on a Philadelphia stage, and fourteen had their first presentation on any stage in this city. There were times when half a dozen travelling companies bid for our patronage each season; now we have one. One year Mr. Hinrichs gave us seven solid months of opera, with seven performances weekly; now we are permitted to attend sixteen performances a year, unless some wandering organization cares to take a chance with us. -

How Musical Is Gesture?

How Musical is Gesture? Mary Ann Smart. 2004. Mimomania: Music and Gesture in Nineteenth-Century Opera. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Reviewed by Gabriela Cruz Sometime in 1852 Louis Bonaparte sat on the grand loge of the Academie Imperiale de Musique for a performance of Jacques Fromental HaUvy's Charles VI (1843). The work, a grandiose national pageant, was a spectacle befitting an emperor forever campaigning for public opinion. In the theater, the man who wished to "appear as the patriarchal benefactor of all classes" (Marx 1996:125) was to be seen surveying the sight of Ie petit peuple as it rushed on stage to save a legitimate dauphin. He was also to lend an ear to the opera's chanson fran~aise, a crowd-pleaser significantly associated with republican patriotism close to the time of the 1848 revolution (Hallman 2003:246). The song, an old soldier's rallying cry against foreign invasion, was sung that night by a young bass-baritone with the right booming voice: Jean Baptiste Meriy. The singer carried the first verse on French courage and abhorrence of oppression. Then, as expected, he pulled a prop dagger above his head and continued with the stirring refrain: Guerre aux tyrans! Jamais en France, Jamais l'Anglais ne regnera. (Act 1, scene 1) [War to all tyrants Never in France, Never shall the English rule.] But here something went amiss. His "Guerre" came out as "mort" and the dagger was seen pointing toward the imperial loge. Song became a call to regicide and amidst the ensuing scandal the singer was quickly dismissed, never to appear again on the imperial stage. -

16 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert Le Diable, 1831. the Nuns' Ballet. Meyerbeer's Synesthetic Cocktail Debuts at the Paris Opera

Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert le diable, 1831. The nuns’ ballet. Meyerbeer’s synesthetic cocktail debuts at the Paris Opera. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 16 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/grey/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/GREY_a_00030/689033/grey_a_00030.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 The Prophet and the Pendulum: Sensational Science and Audiovisual Phantasmagoria around 1848 JOHN TRESCH Nothing is more wonderful, nothing more fantastic than actual life. —E.T.A. Hoffmann, “The Sand-Man” (1816) The Fantastic and the Positive During the French Second Republic—the volatile period between the 1848 Revolution and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état—two striking per - formances fired the imaginations of Parisian audiences. The first, in 1849, was a return: after more than a decade, the master of the Parisian grand opera, Giacomo Meyerbeer, launched Le prophète , whose complex instrumentation and astound - ing visuals—including the unprecedented use of electric lighting—surpassed even his own previous innovations in sound and vision. The second, in 1851, was a debut: the installation of Foucault’s pendulum in the Panthéon. The installation marked the first public exposure of one of the most celebrated demonstrations in the history of science. A heavy copper ball suspended from the former cathedral’s copula, once set in motion, swung in a plane that slowly traced a circle on the marble floor, demonstrating the rotation of the earth. In terms of their aim and meaning, these performances might seem polar opposites. -

![ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1791/robert-le-diable-music-by-giacomo-meyerbeer-libretto-by-eug%C3%A8ne-scribe-germain-delavigne-first-performance-op%C3%A9ra-acad%C3%A9mie-royale-paris-november-21-1831-1191791.webp)

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie Royale], Paris, November 21, 1831

ROBERT LE DIABLE Music by Giacomo Meyerbeer Libretto by Eugène Scribe & Germain Delavigne First Performance: Opéra [Académie royale], Paris, November 21, 1831 Robert, son of Bertha, daughter of the Duke of Normandy (who has been seduced by the Devil), wanders to Palermo in Sicily, where he falls in love with the King's daughter, Isabella, and intends to joust in a tournament to win her. His companion, Bertram (in reality his satanic father), forestalls him at every juncture. A compatriot, the minstrel Raimbaut, warns the company about Robert the Devil, and is about to be hanged when Robert's foster sister Alice appears to save him. She has followed Robert with a message from his dead mother; Robert confides to her his love for Isabella, who has banished him because of his jealousy. Alice promises to help and asks in return that she be allowed to marry Raimbaut. When Bertram enters, she recognizes him and hides. Bertram induces Robert to gamble away all his substance. Alice intercedes for Robert with Isabella, who presents him with a new suit of armor to fight the Prince of Granada, but Bertram lures him away from combat, and the Prince wins Isabella. In the cavern of St. Irene, Raimbaut waits for Alice but is tempted by Bertram with money, which he leaves to spend. Alice enters on a scene which betrays Bertram as an unholy spirit, and in spite of clinging to her cross, is about to be destroyed by Bertram when Robert enters. The young man is desperate and ready to resort to magic arts. -

16 Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert Le Diable, 1831. the Nuns' Ballet

Giacomo Meyerbeer. Robert le diable, 1831. The nuns’ ballet. Meyerbeer’s synesthetic cocktail debuts at the Paris Opera. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 16 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00030 by guest on 25 September 2021 The Prophet and the Pendulum: Sensational Science and Audiovisual Phantasmagoria around 1848 JOHN TRESCH Nothing is more wonderful, nothing more fantastic than actual life. —E.T.A. Hoffmann, “The Sand-Man” (1816) The Fantastic and the Positive During the French Second Republic—the volatile period between the 1848 Revolution and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s 1851 coup d’état—two striking per - formances fired the imaginations of Parisian audiences. The first, in 1849, was a return: after more than a decade, the master of the Parisian grand opera, Giacomo Meyerbeer, launched Le prophète , whose complex instrumentation and astound - ing visuals—including the unprecedented use of electric lighting—surpassed even his own previous innovations in sound and vision. The second, in 1851, was a debut: the installation of Foucault’s pendulum in the Panthéon. The installation marked the first public exposure of one of the most celebrated demonstrations in the history of science. A heavy copper ball suspended from the former cathedral’s copula, once set in motion, swung in a plane that slowly traced a circle on the marble floor, demonstrating the rotation of the earth. In terms of their aim and meaning, these performances might seem polar opposites. Opera aficionados have seen Le prophète as the nadir of midcentury bad taste, demanding correction by an idealist conception of music. Grand opera in its entirety has been seen as mass-produced phantasmagoria, mechani - cally produced illusion presaging the commercial deceptions of the society of the spectacle. -

Download Booklet

Boomin Bass and Bari one BEST LOVED OPERA ARIAS Best loved opera arias for Bass and Baritone 1 Gioachino ROSSINI (1792–1868) 6 Jacques OFFENBACH (1819–1880) 11 Gioachino ROSSINI 15 George Frideric HANDEL (1685–1759) Il barbiere di Siviglia 4:57 Les Contes d’Hoffmann 4:09 Guillaume Tell (‘William Tell’) (1829) 2:41 Acis and Galatea (1718) 3:26 (‘The Barber of Seville’) (1816) (‘The Tales of Hoffmann’) (1881) Act III, Finale – Aria: Sois immobile (Guillaume) Act II – Aria: O ruddier than the cherry Act I – Cavatina: Largo al factotum Act II – Scintille, diamant! (Dappertutto) Andrew Foster-Williams, Bass-baritone (Polyphemus) della città (Figaro) Samuel Ramey, Bass • Munich Radio Orchestra Virtuosi Brunensis • Antonino Fogliani Jan Opalach, Bass • Seattle Symphony Orchestra Lado Ataneli, Baritone Julius Rudel (8.555355) (8.660363-66) Gerard Schwarz (8.572745-46) Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra 7 Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756–1791) 12 Giuseppe VERDI (1813–1901) 16 Gioachino ROSSINI Lodovico Zocche Le nozze di Figaro 4:01 Nabucco (1842) 4:14 Mosè in Egitto 4:55 (8.572438) (‘The Marriage of Figaro’) (1786) Act II, Scene 2 – Recitative: (‘Moses in Egypt’) (1818, Naples version 1819) 2 Georges BIZET (1838–1875) Act I, No. 10 – Aria: Non più andrai (Figaro) Vieni, o Levita! (Zaccaria) Act II – Dal Re de’ Regi (Mosè) Carmen (1875) 4:53 Renato Girolami, Baritone Michele Pertusi, Bass-baritone Lorenzo Regazzo, Bass-baritone Act II – Couplets: Votre toast, je peux Nicolaus Esterházy Sinfonia • Michael Halász Filarmonica Arturo Toscanini Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra vous les rendre (Toreador Song) (Escamillo) (8.660102-04) Orchestra Giovanile della Via Emilia Antonino Fogliani (8.660220-21) Lado Ataneli, Baritone Francesco Ivan Ciampa (Dynamic CDS7867) 8 Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART 17 Giacomo MEYERBEER (1791–1864) Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Die Zauberflöte 2:59 13 Giuseppe VERDI Les Huguenots (‘The Huguenots’) (1836) 3:01 Lodovico Zocche (‘The Magic Flute’) (1791) Rigoletto (1851) 4:16 Act I – Piff, paff, piff, cernons-les! (Marcel) (8.572438) Act II, No.