Identity and Nostalgia in Post-Unification German Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humor Und Kritik in Erzählungen Über Den Alltag in Der DDR. Eine Analyse Am Beispiel Von Am Kürzeren Ende Der Sonnenallee Und in Zeiten Des Abnehmenden Lichts

UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA GRADO EN ESTUDIOS ALEMANES Trabajo de Fin de Grado Humor und Kritik in Erzählungen über den Alltag in der DDR. Eine Analyse am Beispiel von Am kürzeren Ende der Sonnenallee und In Zeiten des abnehmenden Lichts. David Jiménez Urbán Prof. Dr. Patricia Cifre Wibrow Salamanca, 2018 Danksagung Ich danke meiner Mutter für die Unterstützung und meinem Vater (in memoriam) für das Vertrauen. Ich danke Prof. Dr. Patricia Cifre für ihre Leidenschaft für die Literatur. Ich danke den wunderbaren Menschen, die Salamanca in mein Leben gebracht hat, für die reichen Erinnerungen. David Jiménez Urbán Salamanca, 21.06.2018 2 Inhaltverzeichnis 1. Einleitung .................................................................................................................. 4 2. (N)Ostalgie und Humor ............................................................................................. 5 3. Am kürzeren Ende der Sonnenallee: schlechtes Gedächtnis und reiche Erinnerungen .................................................................................................................... 8 4. In Zeiten des abnehmenden Lichts: Verfall einer kommunistischen Familie ......... 12 5. Schlussfolgerungen. ................................................................................................ 15 6. Literaturverzeichnis ................................................................................................. 17 3 1. Einleitung In der Nacht vom Donnerstag, dem 9. November, auf Freitag, den 10. November -

A FILM by Götz Spielmann Nora Vonwaldstätten Ursula Strauss

Nora von Waldstätten Ursula Strauss A FILM BY Götz Spielmann “Nobody knows what he's really like. In fact ‘really‘ doesn't exist.” Sonja CONTACTS OCTOBER NOVEMBER Production World Sales A FILM BY Götz Spielmann coop99 filmproduktion The Match Factory GmbH Wasagasse 12/1/1 Balthasarstraße 79-81 A-1090 Vienna, Austria D-50670 Cologne, Germany WITH Nora von Waldstätten P +43. 1. 319 58 25 P +49. 221. 539 709-0 Ursula Strauss F +43. 1. 319 58 25-20 F +49. 221. 539 709-10 Peter Simonischek E [email protected] E [email protected] Sebastian Koch www.coop99.at www.matchfactory.de Johannes Zeiler SpielmannFilm International Press Production Austria 2013 Kettenbrückengasse 19/6 WOLF Genre Drama A-1050 Vienna, Austria Gordon Spragg Length 114 min P +43. 1. 585 98 59 Laurin Dietrich Format DCP, 35mm E [email protected] Michael Arnon Aspect Ratio 1:1,85 P +49 157 7474 9724 Sound Dolby 5.1 Festivals E [email protected] Original Language German AFC www.wolf-con.com Austrian Film Commission www.oktober-november.at Stiftgasse 6 A-1060 Vienna, Austria P +43. 1. 526 33 23 F +43. 1. 526 68 01 E [email protected] www.afc.at page 3 SYNOPSIS In a small village in the Austrian Alps there is a hotel, now no longer A new chapter begins; old relationships are reconfigured. in use. Many years ago, when people still took summer vacations The reunion slowly but relentlessly brings to light old conflicts in such places, it was a thriving business. -

1961 3 Politmagazine | 1 Nachrichten ● Die Rote Optik (1959) ● Der Schwarze Kanal ● Panorama ● SFB-Abendschau (Alle 13

17 TV- und Filmbeiträge insgesamt. Phase I: 1956 – 1961 3 Politmagazine | 1 Nachrichten ● Die rote Optik (1959) ● Der schwarze Kanal ● Panorama ● SFB-Abendschau (alle 13. August 1961) Politische TV-Magazine stehen im Mittelpunkt dieser zeitlichen Anfangsphase beider deutscher Staaten. Am Beispiel von drei Politmagazinen und einer Nachrichtensendung betrachten wir die Berichterstattung von jenem Tag, der Berlin und Deutschland in zwei Teile trennte. Der 13. August 1961 aus Sicht von Ost und West – Ein Meilenstein der Geschichte. Phase II: 1962 – 1976 3 Filme | Fiktion ● Polizeiruf (1972) ● Blaulicht (1965) – Die fünfte Kolonne (1976) In den 70er Jahren setzte man verstärkt auf Unterhaltungssendungen, in Ost wie West. Eine besondere Rolle spielte dabei die Entwicklung des „Tatort“ (BRD) und des „Polizeiruf“ (DDR), den die DDR als Gegenstück zum westdeutschen Krimi-Format einsetzte. Besonders brisant: Im allerersten „Tatort – Taxi nach Leipzig“ wurde ausgerechnet ein DDR-Schauplatz in Szene gesetzt. Bei „Blaulicht“ und „Die fünfte Kolonne“ bezichtigen sich Ost und West gegenseitig der Spionage. – Spannende Gegensätze in der TV-Unterhaltung. Phase III: 1976 – 1982 4 Magazine | 2 Nachrichten ● Der schwarze Kanal (1976) – ZDF-Magazin (1976) ● Prisma (1970) – Kennzeichen D (1979) ● Aktuelle Kamera (1976) – Tagesschau (1976) Im Mittelpunkt dieses Zeitabschnittes stehen zwei konkurrierende politische Magazine aus Ost und West: „Der schwarze Kanal“ und das „ZDF-Magazin“. Die beiden Nachrichtensendungen „Aktuelle Kamera“ und „Tagesschau“ behandeln die unterschiedliche Darstellung der Ausbürgerung des kritischen DDR-Liedermachers Wolf Biermann. Phase IV: 1983 – 1989 2 Politmagazine | 2 Nachrichten ● Objektiv (1989) – Kontraste (1989) ● Aktuelle Kamera (1989) – Tagesschau (1989) Nachrichten und ihre Verbreitung stehen im Mittelpunkt dieses Themenbereichs. Wie entwickelten sich Informationssendungen in West und Ost. -

The Commoner Issue 13 Winter 2008-2009

In the beginning there is the doing, the social flow of human interaction and creativity, and the doing is imprisoned by the deed, and the deed wants to dominate the doing and life, and the doing is turned into work, and people into things. Thus the world is crazy, and revolts are also practices of hope. This journal is about living in a world in which the doing is separated from the deed, in which this separation is extended in an increasing numbers of spheres of life, in which the revolt about this separation is ubiquitous. It is not easy to keep deed and doing separated. Struggles are everywhere, because everywhere is the realm of the commoner, and the commoners have just a simple idea in mind: end the enclosures, end the separation between the deeds and the doers, the means of existence must be free for all! The Commoner Issue 13 Winter 2008-2009 Editor: Kolya Abramsky and Massimo De Angelis Print Design: James Lindenschmidt Cover Design: [email protected] Web Design: [email protected] www.thecommoner.org visit the editor's blog: www.thecommoner.org/blog Table Of Contents Introduction: Energy Crisis (Among Others) Is In The Air 1 Kolya Abramsky and Massimo De Angelis Fossil Fuels, Capitalism, And Class Struggle 15 Tom Keefer Energy And Labor In The World-Economy 23 Kolya Abramsky Open Letter On Climate Change: “Save The Planet From 45 Capitalism” Evo Morales A Discourse On Prophetic Method: Oil Crises And Political 53 Economy, Past And Future George Caffentzis Iraqi Oil Workers Movements: Spaces Of Transformation 73 And Transition -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

The Salzgitter Archives: West Germany's Answer to East Germany's Human Rights Violations

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 5 Number 1 Spring Symposium - International Business Article 25 Transactions- Tax and Non-Tax Aspects May 2020 The Salzgitter Archives: West Germany's Answer to East Germany's Human Rights Violations Elizabeth A. Lippitt Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Elizabeth A. Lippitt, The Salzgitter Archives: West Germany's Answer to East Germany's Human Rights Violations, 15 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 147 (1986). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. NOTE The Salzgitter Archives: West Germany's Answer to East Germany's Human Rights Violations ELIZABETH A. LIPP=I* INTRODUCTION Since the end of World War II, ties and conflicts between the two Germanies, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Federal Re- public of Germany (FRG), have served as an important barometer of the larger relationship between the Soviet Union and the United States.' While a clearly discernible improvement in the political, economic and cultural climates can be observed in recent years, three major points of contention remain as a basis of conflict between the two countries:, 1) the insistence on the part of the GDR that the West Germans recognize East German citizenship and nationhood;' 2) the demand by the GDR that the 100 kilometer Elbe River border (between the cities of Lauenburg and Schnakenburg) be relocated to the middle of the river, instead of being entirely within the Federal Republic of Germany;4 and 3) the GDR re- quest for the dissolution of the Zentrale Erfassungsstelle der Landesjus- tizverwaltungen in Salzgitter5 (Salzgitter Archives), a West German * Elizabeth A. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

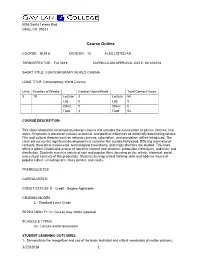

Course Outline 3/23/2018 1

5055 Santa Teresa Blvd Gilroy, CA 95023 Course Outline COURSE: HUM 6 DIVISION: 10 ALSO LISTED AS: TERM EFFECTIVE: Fall 2018 CURRICULUM APPROVAL DATE: 03/12/2018 SHORT TITLE: CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA LONG TITLE: Contemporary World Cinema Units Number of Weeks Contact Hours/Week Total Contact Hours 3 18 Lecture: 3 Lecture: 54 Lab: 0 Lab: 0 Other: 0 Other: 0 Total: 3 Total: 54 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class introduces contemporary foreign cinema and includes the examination of genres, themes, and styles. Emphasis is placed on cultural, economic, and political influences as artistically determining factors. Film and cultural theories such as national cinemas, colonialism, and orientalism will be introduced. The class will survey the significant developments in narrative film outside Hollywood. Differing international contexts, theoretical movements, technological innovations, and major directors are studied. The class offers a global, historical overview of narrative content and structure, production techniques, audience, and distribution. Students screen a variety of rare and popular films, focusing on the artistic, historical, social, and cultural contexts of film production. Students develop critical thinking skills and address issues of popular culture, including race, class gender, and equity. PREREQUISITES: COREQUISITES: CREDIT STATUS: D - Credit - Degree Applicable GRADING MODES L - Standard Letter Grade REPEATABILITY: N - Course may not be repeated SCHEDULE TYPES: 02 - Lecture and/or discussion STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Demonstrate the recognition and use of the basic technical and critical vocabulary of motion pictures. 3/23/2018 1 Measure of assessment: Written paper, written exams. Year assessed, or planned year of assessment: 2013 2. Identify the major theories of film interpretation. -

Copyright by Sebastian Heiduschke 2006

Copyright by Sebastian Heiduschke 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Sebastian Heiduschke Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Afterlife of DEFA in Post-Unification Germany: Characteristics, Traditions and Cultural Legacy Committee: Kirsten Belgum, Supervisor Hans-Bernhard Moeller, Co-Supervisor Pascale Bos David Crew Janet Swaffar The Afterlife of DEFA in Post-Unification Germany: Characteristics, Traditions and Cultural Legacy by Sebastian Heiduschke, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Dedication Für meine Familie Acknowledgements First and foremost it is more than justified to thank my two dissertation advisers, Kit Belgum and Bernd Moeller, who did an outstanding job providing me with the right balance of feedback and room to breathe. Their encouragement, critical reading, and honest talks in the inevitable times of doubt helped me to complete this project. I would like to thank my committee, Pascale Bos, Janet Swaffar, and David Crew, for serving as readers of the dissertation. All three have been tremendous inspirations with their own outstanding scholarship and their kind words. My thanks also go to Zsuzsanna Abrams and Nina Warnke who always had an open ear and an open door. The time of my research in Berlin would not have been as efficient without Wolfgang Mackiewicz at the Freie Universität who freed up many hours by allowing me to work for the Sprachenzentrum at home. An invaluable help was the library staff at the Hochschule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf” Babelsberg . -

Deutschland 83 Is Determined to Stake out His Very Own Territory

October 3, 1990 – October 3, 2015. A German Silver Wedding A global local newspaper in cooperation with 2015 Share the spirit, join the Ode, you’re invited to sing along! Joy, bright spark of divinity, Daughter of Elysium, fire-inspired we tread, thy Heavenly, thy sanctuary. Thy magic power re-unites all that custom has divided, all men become brothers under the sway of thy gentle wings. 25 years ago, world history was rewritten. Germany was unified again, after four decades of separation. October 3 – A day to celebrate! How is Germany doing today and where does it want to go? 2 2015 EDITORIAL Good neighbors We aim to be and to become a nation of good neighbors both at home and abroad. WE ARE So spoke Willy Brandt in his first declaration as German Chancellor on Oct. 28, 1969. And 46 years later – in October 2015 – we can establish that Germany has indeed become a nation of good neighbors. In recent weeks espe- cially, we have demonstrated this by welcoming so many people seeking GRATEFUL protection from violence and suffer- ing. Willy Brandt’s approach formed the basis of a policy of peace and détente, which by 1989 dissolved Joy at the Fall of the Wall and German Reunification was the confrontation between East and West and enabled Chancellor greatest in Berlin. The two parts of the city have grown Helmut Kohl to bring about the reuni- fication of Germany in 1990. together as one | By Michael Müller And now we are celebrating the 25th anniversary of our unity regained. -

Censorship, News Falsification, and Disapproval in 1989 East Germany

Sometimes Less Is More: Censorship, News Falsification, and Disapproval in 1989 East Germany Christian Glaßel¨ University of Mannheim Katrin Paula University of Mannheim Abstract: Does more media censorship imply more regime stability? We argue that censorship may cause mass disapproval for censoring regimes. In particular, we expect that censorship backfires when citizens can falsify media content through alternative sources of information. We empirically test our theoretical argument in an autocratic regime—the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Results demonstrate how exposed state censorship on the country’s emigration crisis fueled outrage in the weeks before the 1989 revolution. Combining original weekly approval surveys on GDR state television and daily content data of West German news programs with a quasi-experimental research design, we show that recipients disapproved of censorship if they were able to detect misinformation through conflicting reports on Western television. Our findings have important implications for the study of censoring systems in contemporary autocracies, external democracy promotion, and campaigns aimed at undermining trust in traditional journalism. Verification Materials: The data, code, and materials required to verify the computational reproducibility of the results, procedures, and analyses in this article are available on the American Journal of Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AZFHYN. The German censors idiots . —Heinrich Heine, Reisebilder, -

Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies 4-50 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E8 Table of Contents

CIUS University of Alberta 1976-2001 2001 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies 4-50 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E8 Table of Contents Telephone: (780) 492-2972 FAX: (780) 492-4967 From the Director 1 E-mail: [email protected] CIUS Website: http://www.ualberta.ca/CIUS/ Investing in the Future of Ukrainian Studies 4 Bringing Scholars Together and Sharing Research 9 Commemorative Issue Cl US Annual Review: The Neporany Postdoctoral Fellowship 12 Reprints permitted with acknowledgement Supporting Ukrainian Scholarship around the World 14 ISSN 1485-7979 Making a Difference through Service to Ukrainian Editor: Bohdan Nebesio Bilingual Education 21 Translator: Soroka Mykola Making History while Exploring the Past 24 Editorial supervision: Myroslav Yurkevich CIUS Press 27 Design and layout: Peter Matilainen Cover design: Penny Snell, Design Studio Creative Services, Encyclopedia of Ukraine Project 28 University of Alberta Promoting Ukrainian Studies Where Most Needed 30 Examining the Ukrainian Experience in Canada 32 To contact the CIUS Toronto office (Encyclopedia Project or CIUS Press), Keeping Pace with Kyiv 34 please write c/o: Linking Parliaments of Ukraine and Canada 36 CIUS Toronto Office Raising the Profile of Ukrainian Literature 37 University of Toronto Presenting the Ukrainian Religious Experience to 1 Spadina Crescent, Room 1 09 the World 38 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2J5 Periodical Publications 39 Telephone: Endowments 40 General Office 978-6934 (416) Donors to CIUS Endowment Funds 44 CIUS