The Conflicted Artist- an Analysis of the Aesthetics of German Idealism in E.T.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A FILM by Götz Spielmann Nora Vonwaldstätten Ursula Strauss

Nora von Waldstätten Ursula Strauss A FILM BY Götz Spielmann “Nobody knows what he's really like. In fact ‘really‘ doesn't exist.” Sonja CONTACTS OCTOBER NOVEMBER Production World Sales A FILM BY Götz Spielmann coop99 filmproduktion The Match Factory GmbH Wasagasse 12/1/1 Balthasarstraße 79-81 A-1090 Vienna, Austria D-50670 Cologne, Germany WITH Nora von Waldstätten P +43. 1. 319 58 25 P +49. 221. 539 709-0 Ursula Strauss F +43. 1. 319 58 25-20 F +49. 221. 539 709-10 Peter Simonischek E [email protected] E [email protected] Sebastian Koch www.coop99.at www.matchfactory.de Johannes Zeiler SpielmannFilm International Press Production Austria 2013 Kettenbrückengasse 19/6 WOLF Genre Drama A-1050 Vienna, Austria Gordon Spragg Length 114 min P +43. 1. 585 98 59 Laurin Dietrich Format DCP, 35mm E [email protected] Michael Arnon Aspect Ratio 1:1,85 P +49 157 7474 9724 Sound Dolby 5.1 Festivals E [email protected] Original Language German AFC www.wolf-con.com Austrian Film Commission www.oktober-november.at Stiftgasse 6 A-1060 Vienna, Austria P +43. 1. 526 33 23 F +43. 1. 526 68 01 E [email protected] www.afc.at page 3 SYNOPSIS In a small village in the Austrian Alps there is a hotel, now no longer A new chapter begins; old relationships are reconfigured. in use. Many years ago, when people still took summer vacations The reunion slowly but relentlessly brings to light old conflicts in such places, it was a thriving business. -

The Commoner Issue 13 Winter 2008-2009

In the beginning there is the doing, the social flow of human interaction and creativity, and the doing is imprisoned by the deed, and the deed wants to dominate the doing and life, and the doing is turned into work, and people into things. Thus the world is crazy, and revolts are also practices of hope. This journal is about living in a world in which the doing is separated from the deed, in which this separation is extended in an increasing numbers of spheres of life, in which the revolt about this separation is ubiquitous. It is not easy to keep deed and doing separated. Struggles are everywhere, because everywhere is the realm of the commoner, and the commoners have just a simple idea in mind: end the enclosures, end the separation between the deeds and the doers, the means of existence must be free for all! The Commoner Issue 13 Winter 2008-2009 Editor: Kolya Abramsky and Massimo De Angelis Print Design: James Lindenschmidt Cover Design: [email protected] Web Design: [email protected] www.thecommoner.org visit the editor's blog: www.thecommoner.org/blog Table Of Contents Introduction: Energy Crisis (Among Others) Is In The Air 1 Kolya Abramsky and Massimo De Angelis Fossil Fuels, Capitalism, And Class Struggle 15 Tom Keefer Energy And Labor In The World-Economy 23 Kolya Abramsky Open Letter On Climate Change: “Save The Planet From 45 Capitalism” Evo Morales A Discourse On Prophetic Method: Oil Crises And Political 53 Economy, Past And Future George Caffentzis Iraqi Oil Workers Movements: Spaces Of Transformation 73 And Transition -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

Course Outline 3/23/2018 1

5055 Santa Teresa Blvd Gilroy, CA 95023 Course Outline COURSE: HUM 6 DIVISION: 10 ALSO LISTED AS: TERM EFFECTIVE: Fall 2018 CURRICULUM APPROVAL DATE: 03/12/2018 SHORT TITLE: CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA LONG TITLE: Contemporary World Cinema Units Number of Weeks Contact Hours/Week Total Contact Hours 3 18 Lecture: 3 Lecture: 54 Lab: 0 Lab: 0 Other: 0 Other: 0 Total: 3 Total: 54 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class introduces contemporary foreign cinema and includes the examination of genres, themes, and styles. Emphasis is placed on cultural, economic, and political influences as artistically determining factors. Film and cultural theories such as national cinemas, colonialism, and orientalism will be introduced. The class will survey the significant developments in narrative film outside Hollywood. Differing international contexts, theoretical movements, technological innovations, and major directors are studied. The class offers a global, historical overview of narrative content and structure, production techniques, audience, and distribution. Students screen a variety of rare and popular films, focusing on the artistic, historical, social, and cultural contexts of film production. Students develop critical thinking skills and address issues of popular culture, including race, class gender, and equity. PREREQUISITES: COREQUISITES: CREDIT STATUS: D - Credit - Degree Applicable GRADING MODES L - Standard Letter Grade REPEATABILITY: N - Course may not be repeated SCHEDULE TYPES: 02 - Lecture and/or discussion STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Demonstrate the recognition and use of the basic technical and critical vocabulary of motion pictures. 3/23/2018 1 Measure of assessment: Written paper, written exams. Year assessed, or planned year of assessment: 2013 2. Identify the major theories of film interpretation. -

History, Art and Shame in Von Donnersmarck's the Lives of Others

History, Art and Shame in von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others Hans Löfgren University of Gothenburg Abstract. Commentary on the successful directing and scriptwriting debut of Florian von Donnersmarck, The Lives of Others, tends to divide into those faulting the film for its lack of historical accuracy and those praising its artistry and conciliatory symbolic function after the reunification of the GDR and BRD. This essay argues that even when we grant the film’s artistic premise that music can convert the socialist revolutionary into a peaceful liberal, suspending the demand for realism, the politics intrinsic to the film still leads to a problematic conclusion. The stern Stasi officer in charge of the surveillance of a playwright and his actress partner comes to play the part of a selfless savior, while the victimized actress becomes a betrayer. Her shame however, is not shared by the playwright, Dreyman, and the Stasi officer, Wiesler, who never meet eye to eye but instead become linked in a mutual gratitude centering on the book dedicated to Wiesler, written years later when Dreyman learns of the other’s having subversively protected him from imprisonment. Despite superb acting and directing, dependence on such tenuous character development makes the harmonious conclusion of the film ring hollow and implies the need for more serious challenges to German reunification. Keywords. Film, Germany, reunification, symbolic reconciliation, art, humanism, surveillance. Every step you take I’ll be watching you . Oh, can’t you see You belong to me The Police We are accustomed to saying that beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder, and we could easily expand that point by unpacking its figurative meaning, stating more prosaically that an indefinite range of beliefs, values, sentiments and sensations is often ascribed by a spectator, reader, or listener to the text an sich. -

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT Solved! the Mystery Motors of the Autosafe “Skypark”…

2 MAR 18 5 APR 18 1 | 2 MAR 18 - 5 APR 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT Solved! The Mystery Motors of the Autosafe “SkyPark”… Huge thanks to a number of you out there who sent me a link to the BBC News article that finally puts the issue I’ve been bleating on about for months (see Filmhouse December and February monthly programme introductions) to bed. Turns out the eight cars that have been trapped in the failed then abandoned automated car park (which is currently being dismantled behind our offices) since it closed in the early 2000s were only ever old bangers brought in to test the automatic parking machinery! Phew! Glad to have gotten to the bottom of that one… Our March programme, as is customary for the time of year, is replete with Oscar® hopefuls, it now being the turn of Lady Bird, Phantom Thread (in 70mm!), A Fantastic Woman, Palme d’Or winner The Square, and The Shape of Water, which continues from February. Awards season is, though, nearly over, as is evidenced by a slew of new films too new to qualify for consideration this year: Lynne Ramsay’s brilliant You Were Never Really Here; Warwick (Samson & Delilah) Thornton’s stunning Aussie ‘western’, Sweet Country, and Wes Anderson’s fabulous Isle of Dogs. And you know what, looking at that list, I’m going to stick my neck out and say that I’m not entirely sure I have ever seen a better line-up of new release cinema, at any one cinema, ever. -

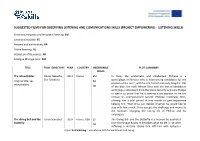

Project Empowering - Listening Skills)

SUGGESTED FILMS FOR OBSERVING LISTENING AND COMUNICATIONS SKILLS (PROJECT EMPOWERING - LISTENING SKILLS) Emotions, empathy and empathic listening: EM Emotional stability: ES Respect and authenticity: RA Active listening: AL Activation of Resources: AR Dialogue Management: DM TITLE FILM DIRECTOR YEAR COUNTRY OBSERVABLE PLOT SUMMARY SKILLS The Intouchables Olivier Nakache, 2011 France EM In Paris, the aristocratic and intellectual Philippe is a Original title: Les Éric Toledano RA quadriplegic millionaire who is interviewing candidates for the intouchables position of his carer, with his red-haired secretary Magalie. Out AR of the blue, the rude African Driss cuts the line of candidates and brings a document from the Social Security and asks Phillipe to sign it to prove that he is seeking a job position so he can receive his unemployment benefit. Philippe challenges Driss, offering him a trial period of one month to gain experience helping him. Then Driss can decide whether he would like to stay with him or not. Driss accepts the challenge and moves to the mansion, changing the boring life of Phillipe and his employees. The diving bell and the Julian Schnabel 2007 France, USA ES The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is a memoir by journalist butterfly AR Jean-Dominique Bauby. It describes what his life is like after suffering a massive stroke that left him with locked-in Project EmPoWEring - Educational Path for Emotional Well-being Original title: Le DM syndrome. It also details what his life was like before the scaphandre et le stroke. papillon On December 8, 1995, Bauby, the editor-in-chief of French Elle magazine, suffered a stroke and lapsed into a coma. -

Saffron Screen

It is often said that Poland has too much history to digest. Perhaps because of this, there has been a tendency for the country to try to make sense of itself through the medium of film. Polish movies have provided European culture with some of the most extraordinary and enigmatic films in the past 50 years. £5 for all tickets £20 festival ticket for entrance to all films Tickets are available online, from the Tourist Information Centre, or at the box office All films are in Polish with English subtitles Saffron Screen Audley End Road, Saffron Walden CB11 4UH Festiwal Filmów Polskich Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01799 500238 OSCAR WINNER √ASHES AND DIAMONDS √IDA √BOGOWIE √KNIFE IN THE WATER www.design-mill.co.uk www.saffronscreen.com √ KANAL We are delighted to present you with a selection of Polish films, showcasing a √IDA range of directors, genres and moods to give you a sample of the rich culture √A SHORT FILM ABOUT KILLING √VINCI and history of this fascinating country. √THERE AND BACK Saturday 9 May Films from the 21st century Saturday 16 May Tragedy and comedy IDA (12A) 5pm A SHORT FILM ABOUT KILLING (18) 5pm DIRECTOR3DZHá3DZOLNRZVNL (Krótki #lm o zabijaniu) CAST$JDWD7U]HEXFKRZVND$JDWD.XOHV]D'DZLG2JURGQLN-HU]\7UHOD DIRECTOR.U]\V]WRI.LHĞORZVNL SCREEN TEST:HDUHGHOLJKWHGWRODXQFKRXUIHVWLYDOE\EULQJLQJEDFNWKLVPRYLQJ CAST0LURVáDZ%DND.U]\V]WRI*ORELV]-DQ7HVDU]=ELJQLHZ=DSDVLHZLF] DQGLQWLPDWHGUDPDZLQQHURIWKLV\HDU¶V2VFDUIRU%HVW)RUHLJQ/DQJXDJH)LOP6HW SCREEN TEST 7KHSDWKVRIWKUHHXQUHODWHGPHQFURVVRQHVRPEUH0DUFKGD\LQ LQV3RODQGWKLVLVWKHVWRU\RID\RXQJQRYLWLDWHQXQ$QQDZKRLVVHQWWRPHHW -

German Teachers' Resources Teaching Film And

GERMAN TEACHERS’ RESOURCES TEACHING FILM AND LITERATURE FOR AS AND A2 STUDYING: DER BESUCH DER ALTEN DAME FRIEDRICH DÜRRENMATT DER VORLESER BERNHARD SCHLINK GOOD BYE, LENIN! DIRECTED BY WOLFGANG BECKER DAS LEBEN DER ANDEREN DIRECTED BY FLORIAN HENCKEL VON DONNERSMARCK CONTENTS USING THESE RESOURCES .................................................................................................. 3 TEXT ANALYSIS Der Besuch der alten Dame by Friedrich Dürrenmatt .................................................................. 4 Der Vorleser by Bernhard Schlink ................................................................................................ 8 Good Bye, Lenin! directed by Wolfgang Becker ........................................................................... 12 Das Leben der Anderen directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck .................................... 15 2 INTRODUCTION AND RESOURCE RATIONALE These resources have been developed in response to changes in the content of the AS/A2 curricula for modern foreign languages (French, Spanish and German), which are effective from September 2016. They have been designed to give support and guidance to MFL teachers in selecting and teaching the film and literature content of the curricula. There are five sections to this resource: 1. Why teach this text? d. Cinematography/form and genre This section explains the relevance and benefits of The cinematography sub-section focuses on directorial teaching this text/film for teachers and their students. It and cinematographic technique in films. It aims to guide also describes how the text/film fits in to the A-level as a teachers who may not be familiar with teaching film. whole, as well as its links with other A-level subjects. This sub-section is particularly useful for AS and A2 exam questions that deal with colour, sound, directorial technique, etc. 2. Ways to read this text This section briefly describes the different critical lenses The form and genre sub-section focuses on the for reading a text/film, as well as outlining different themes. -

E Newsletter

THE CLEVELAND CULTURAL GARDENS FEDERATION E Newsletter Summer 2013 July 2013 In this issue: Bands in the German Garden, July 14th Brass Bands Brass bands and yodeling will be heard in the Opera German Garden on Sunday, July 14th from 1:00pm to OWD about 2:30pm. President’s notes As in the past years, this concert is a treat to all Installation dinner music lovers, with large bands and choirs performing Hawken plans Juneteenth under the watchful eye of larger than life statues of Kiosk Schiller and Goethe. Bring your own seating, be it a Volunteers lawn chair or a blanket. Film fest Italian Garden to Host Opera, July 21st Once again Opera Per Tutti will perform in the Italian Garden on Sunday, July 21st at 6:00pm. But come early to get a good seat - last year this GARDEN WEB SITES: event drew over 1,200 people! 250 chairs will be provided, however most Cultural Gardens Sites attendees bring their own law chairs or blankets for a www.culturalgardens.org late afternoon picnic. Free wine and wood oven pizza clevelandculturalgardens.org will be available, or you can bring your own. Czech Garden czechculturalgarden.webs.com. This event has become a tradition. It is Irish Garden presented by the Italian Cultural Garden Foundation‘s www.irishgardenclub.org “Viva! Cultura Italiana” cultural series. Thank you Hungarian Garden Joyce Mariani and all involved with the production. hungarianculturalgarden.org Slovenian Garden www.cleslo.com/scga/ One World Day–Worldfest, August 25th Serbian Garden The 66th One World Day celebration will take serbianculturalgarden.org on a new, larger format this year. -

1 Boston University Study Abroad London European Cinema

Boston University Study Abroad London European Cinema: From Festival Circuit to the Big Screen (Elective B Course) Instructor Information A. Name Ms Kate Domaille B. Day and Time TBA C. Location 43 Harrington Gardens, SW7 4JU D. BU Telephone 020 7244 6255 E. Office Telephone 020 7263 5618 F. Email Kad63@bu-edu [email protected] G. Office hours By appointment Course Objectives This course is an examination of contemporary European cinema and asks the key question: what do national cinema products reveal about national identity, culture, and values? The course will combine a study of the economics and cultural politics of national cinemas in Europe and their existence within a global marketplace of film. Through the study of film festivals, and the study of filmmakers and their films, students will have an opportunity to examine how minor cinemas evolve to be significant for national audiences and how these cinemas convey aspects of culture, language and social life across national boundaries. Central questions addressed by the course include: What are the conditions for European film production and distribution of cinema within and beyond the nation state? Why are national film cultures important to retain? What function and value do film festivals have in promoting films? What do representations of film cultures both in-nation and beyond nation tell audiences of cultural values across the world? The course will draw upon literature about film festival success, and where possible, give direct experience of film festivals either through following a programme remotely or a trip to one of the London film festivals. -

Identity and Nostalgia in Post-Unification German Cinema

In the Eye of the Beholder: Identity and Nostalgia in Post-Unification German Cinema Joshua S. Zmarzly History 489 May 12, 2014 Abstract In this study, I wish to examine several films produced in the decades after German Unification (die Wende) to show their relation to themes of identity, historical memory, and nostalgia in the culture of former East Germans. The prevailing subject I seek to research in this context of cinema and historical memory is “osatalgia” (German: “ost” [east] + “nostalgie” [nostalgia]), a pop culture movement dedicated to celebrating and reclaiming aspects (usually material) from the East German past. It’s a day in 1990. East Berlin still lies on one side of the epicenter of the Cold War ideological stand-off, and as Erich Honecker, chairman of East Germany’s sole political party, steps down and as he is replaced with former cosmonaut and socialist hero, Sigmund Jähn, the borders of East Germany are opened. Thousands of West Germans, tired of their meaningless lives in the decadent, corrupt Federal Republic of Germany, flood into the East. Eventually, West Germans begin to break apart the Berlin Wall, that concrete seam of the Iron Curtain, in order to join the socialist utopia of the German Democratic Republic. In his small, government-provided flat, Alex Kerner and his family watch joyously as the state news program, Aktuelle Kamera, announces the fall of the West. Fireworks burst into clouds of colorful light in the distance. And all of it is a lie. It’s a lie created by Alex to keep the GDR, in reality swallowed up whole by the capitalist West, alive.