Evaluation of the Level of Contaminants, Mercury, Arsenic, Nickel and Cadmium in Fiddleheads, New Brunswick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Coconut Extract on Callus Growth and Ultrasound Waves On

Folia Forestalia Polonica, Series A – Forestry, 2018, Vol. 60 (4), 261–268 METHODOLOGICAL ARTICLE DOI: 10.2478/ffp-2018-0027 The effect of coconut extract on callus growth and ultrasound waves on production of betulin and betulinic acid in in-vitro culture conditions of Betula pendula Roth species Vahide Payamnoor1 , Razieh Jafari Hajati2, Negar Khodadai1 1 Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Faculty of Forest Sciences, Gorgan, Iran, phone: 0098-9113735812, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Shahed University, Traditional Clinical Trial Research Center, Tehran, Iran AbstrAct To determine the effect of coconut extract on callogenesis of Betula pendula, Roth stem barks were cultured in NT (Nagata and Takebe) basic culture media in two individual experiments: i) cultivation explant in different treat- ments of coconut extracts combined with 1 mg l-1 2, 4-D (2, 4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) and ii) callogenesis in NT media containing 1.5 mg l-1 2,4-D and 0.5 mg l-1 BAP (6-Benzylaminopurine) and then cultivation under the first experiment treatments. The first experiment demonstrated that not all concentrations of coconut extracts lead to callus induction individually, but callus induction increased 84% in a culture containing 5% coconut extract plus 1 mg l-1 2, 4-D. Based on the results of the second experiment, this treatment also significantly increased the wet and dry weights of the produced calluses. The possibility of increasing the betulinic acid and betulin by ultrasound was also studied. Samples cultivated in the selected culture medium were exposed to ultrasound waves in two forms of 1) one exposure and 2) twice exposure (repetition with 24 hr interval) in steps of 20, 60, 100, and 160 sec, and one treatment as the control. -

Invent Your Scent

JULY 2020 Invent your Scent All Scent Plus Melts RRP $12.50 1. Your Warmer 2. Your Scent 3. Your Way Choose your Warmer Choose a Scent Plus Melts Invent your Scent ScentGlow™ Warmers provide Scent Plus™ Melts are available Customise by pairing two fragrance without the flame in dozens of PartyLite exclusive different Scent Plus Melts or while fragrance warmers use a fragrances. Enjoy hours of rich try one of our fragrance mixing tealight. Both come in an array home fragrance from our most recipes tested by the best of decorative styles - there’s one highly scented wax formula. noses in the business. for every room in the house. While stocks last. PartyLite reserves the right to put products on stop sell at any time. JULY 2020 Invent your Scent 1. Choose a Warmer (Colour Illusions appear in a dark room) Champagne Glow Pineapple Snow Flurry Cable Knit RRP $65.00 RRP $60.00 RRP $65.00 RRP $60.00 P92588A P92688A P92555A P93128A Pearl Oyster Spiral Sea Shell Mystic Glimmer RRP $65.00 RRP $60.00 RRP $60.00 RRP $65.00 P93041A P91897A P92685A P93160A 2. Choose a Scent (All Scent Plus Melts $12.50 RRP Each) VOLUME 2 2020 SCENT PLUS MELTS SX1045 AMBER SUEDE SX900 MARSHMALLOW VANILLA SX1020 TAMBOTI WOODS SX1047 CASHMERE CASSIS SX29 MULBERRY SX929 VANILLA COCONUT SX821 FIG FATALE SX1031 RASPBERRY RHUBARB SX1046 VELVET PLUM SX123 ICED SNOWBERRIES™ SX927 SUN-KISSED LINEN SX1029 WHITE LILAC & IVY SX1038 MANGO MAGIC OUT OF CATALOGUE SCENT PLUS MELTS SX1022 AMBER APPLEWOOD SX1043 GARDEN HERBS SX938 PERSIMMON CIDER SX776Q AUTUMN GLOW SX1055 HOLLY JOLLY BERRY SX789 PINK GRAPEFRUIT SX922Q BALSAM SNOW SX1024 MOUNTAIN RETREAT SX942 SILVER BIRCH BARK SX1018 BELLINI GLITTER SX1012 MULLED HARVEST SPICE SX1057 SPICED POMANDER SX1059 BLACK CHERRY ORCHARD SX783 MYSTERY POTION SX1054 WHISKEY TODDY SX937 BLACKBERRY CEDAR LEAF SX1044 OLIVE GROVE SX941Q BLUE SPRUCE SX1021 CHRYSANTHEMUM CEDARWOOD 3. -

Minnesota Harvester Handbook

Minnesota Harvester Handbook sustainable livelihoods lifestyles enterprise Minnesota Harvester Handbook Additonal informaton about this resource can be found at www.myminnesotawoods.umn.edu. ©2013, Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Send copyright permission inquiries to: Copyright Coordinator University of Minnesota Extension 405 Cofey Hall 1420 Eckles Avenue St. Paul, MN 55108-6068 Email to [email protected] or fax to 612-625-3967. University of Minnesota Extension shall provide equal access to and opportunity in its programs, facilites, and employment without regard to race, color, creed, religion, natonal origin, gender, age, marital status, disability, public assistance status, veteran status, sexual orientaton, gender identty, or gender expression. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilites Act, this publicaton/material is available in alternatve formats upon request. Direct requests to the Extension Regional Ofce, Cloquet at 218-726-6464. The informaton given in this publicaton is for educatonal purposes only. Reference to commercial products or trade names is made with the understanding that no discriminaton is intended and no endorsement by University of Minnesota Extension is implied. Acknowledgements Financial and other support for the Harvester Handbook came from University of Minnesota Extension, through the Extension Center for Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences (EFANS) and the Northeast Regional Sustainable Development Partnership (RSDP). Many individuals generously contributed to the development of the Handbook through original research, authorship of content, review of content, design and editng. Special thanks to Wendy Cocksedge and the Centre for Livelihoods and Ecology at Royal Roads University for their generosity with the Harvester Handbook concept. A special thanks to Trudy Fredericks for her tremen- dous overall eforts on this project. -

Special (Secondary) Metabolites from Wood

10 Special (Secondary) Metabolites from Wood JOHN R. Obst 10.1 Introduction Flavonoids, lignans, terpenes, phenols, aikaloids, sterols, waxes, fats, tannins, sugars, gums, suberins, resin acids and carotenoids are among the many classes of com- pounds known as ‘secondary metabolites’. This daunting array of substances, having different chemical, physical and biological properties, presents numerous challenges in the utilization of forest products. Do they also present opportunities? Secondary metabolites are often defined on the basis of what they are not. To wit, primary metabolites are usually desecribed as those substances that are the fundamental chemical units of living plant cells, such as nucleic acids, proteins and polysaccharides. Secondary metabotites may therefore be defined as being every- thing else that the organism produces. Intuitively, this definition is a little difficult to accept: why would a plant expend so much energy to produce matetials that it does not need? Especially because some of these ‘secondary’ compounds are vital to its very existence. In the realm of wood processing and utilization, there is a very pragmatic defini- tion of secondary metabolites: they are everything that is not a structural poly- saccharide or lignin. In this sense, secondary metabolites are often referred to as ‘extraneous components’ because they are mostly extraneous to the lignocellulosic cell wall and are concentrated in resin canals and cell lumina especially those of ray parenchyma cells. These types of compounds are however actually found in all mor- phological regions and this definition cannot be strictly applied. While such a definition emphasizing the structural components of wood is very functional, it can give the impression of demeaning the role of these “extraneous components’. -

Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-Mile Loop, Strenuous

Natural Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-mile loop, strenuous n the flanks and summit of Speckled Mountain, human and natural history mingle. An old farm Oroad meets a fire tower access path to lead you through a menagerie of plants, animals, and natural communities. On the way down Blueberry Ridge, 0with0.2 a sea 0.4 of blueberry 0.8 bushes 1.2 at 1.6 your feet and spectacular views around every bend, the rewards of the summit seem endless. Miles Getting There Click numbers to jump to descriptions. From US Route 2 in Gilead, travel south on Maine State Route 113 for 10 miles to the parking area at Brickett Place on the east side of the road. From US Route 302 in Fryeburg, travel north on Maine State Route 113 for 19 miles to Brickett Place. 00.2 0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 Miles A House of Many Names -71.003608, 44.267292 Begin your hike at Brickett Place Farm. In the 1830s, a century before present-day Route 113 sliced through Evans Notch, John Brickett and Catherine (Whitaker) Brickett built this farmhouse from home- made bricks. Here, they raised nine children alongside sheep, pigs, cattle, and chick- ens. Since its acquisition by the White Mountain National Forest in 1918, Brickett Place Farmhouse has served as Civilian Conservation Corps headquarters (1930s), Cold River Ranger Station (1940s), an Appalachian Mountain Club Hut (1950s), and a Boy Scouts of America camp (1960-1993). Today, Brickett Place Farmhouse has gone through a thorough restoration and re- mains the oldest structure in the eastern region of the Forest Service. -

View Andersen

Unlimited Possibilities to Create Your Original. Create Your Original The inspiration for your home can come from anywhere and with E-Series windows and patio doors from Andersen, you'll find custom colors, unlimited design options and dynamic sizes and shapes to create the home you've always imagined. Whether you're looking to make a design statement or to simply recreate a classic, E-Series products give you more freedom to use your imagination and create your personal vision of home. And like all Andersen products, they are supported by over 115 years of commitment to quality and service that can only come from one of the most trusted names in the industry. For more information, please visit andersenwindows.com/e-series. 2 Modern Style Made Easy Modern home styles incorporate clean lines, simple forms and open floor plans. They often feature floor-to-ceiling FSB® hardware windows or glass doors with narrow profiles to maximize features clean lines in a satin finish for light and bring the outdoors in. Explore our Home Style a thoroughly modern look. library to see how E-Series products can help you achieve a modern home style. Visit andersenwindows.com/stylelibrary to learn more. Dark colors and narrow profile options on windows, patio doors and grille options offer a truly contemporary style. Industrial Modern 3 E-Series picture windows with dark bronze exteriors. E-Series trapezoid and awning windows with custom exteriors. Do You Dream in Color? With E-Series windows and patio doors, you have the freedom to choose from 50 exterior colors. -

Forests, Fire, and Culture: Silvicultral & Fire Treatments to Enhance Nontimber Forest Products

Forests, Fire, and Culture: Silvicultral & Fire Treatments to Enhance Nontimber Forest Products Marla R. Emery, Ph.D. USFS Northern Research Station NTFPs = Cultural resources “not much less necessary to the existence of the Indians than the atmosphere they breathe(d).” U.S. vs. Winans (198 U.S. 371, 381; 1905) Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen Culture/Economy • Significant economic resources Broader definition of economic Economic scales • Essential cultural resources Identity Practices Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen Sensitive resources • Food Public • Artisanal & utilitarian Culture • Medicinal Sacred & Proprietary • Spiritual & ceremonial Culture Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen NTFPs @ every phase • Who • What • When • Where • Why • How (Not necessarily in that order) Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen What • Species • Parts • Characteristics Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen Who Last First Contact NTFP 1 NTFP2 NTFP 3… name name Benedict Mike XXX-XXXX Black ash Sweetgrass Birch bark Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen Where • Your expertise & observations • Traditional ecological knowledge • Scientific & amateur literature • Amazing what’s on the internet! Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen When • Annually • Stand development & management phase Safe-title box: anything outside of this box may be cut off on the screen Annually Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Basswood bark Birch bark Blueberries Boughs Cedar greens Fiddleheads Goldthread Morels Princess Pine Red willow bark Sketaugen Stage of Stand Development Other plant products Products from trees Small stems/branches/bark--decorative, Regeneration Regeneration furniture --Clearcut/ Berries; Weeding Residuals Cleaning --Shelterwood hazel Small stems--decorative, furniture --Site prep. -

Non-Timber Forest Products By: Glen Holt RREA Forestry Program Adjunct Forester

Shoulder Season Income Opps with Non-Timber Forest Products by: Glen Holt RREA Forestry Program Adjunct Forester UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS Non-Timber Forest Products? • Plants, animals, minerals and other biological organisms that people have gathered and used to maintain life and livelihood in the boreal and cold temperate forest regions since the first people inhabited this region. • Every culture of all nationalities throughout the circumpolar region gathered and used non-timber forest products. • NTFP’s are other than derived from cutting and processing trees into milled and manufactured products including lumber, cabin logs, pulp, chemicals, etc. • Much emphasis has previously focused on tropical forest NTFP’s and the indigenous peoples that still use them as a major part of their living and culture. A broad definition of NTFPs: those biological organisms, excluding timber, valued by humans for both consumptive and non-consumptive purposes found in various forms within the forested landscape. Non-Timber Forest Products termed NTFPs are listed nationwide in part as: • Floral greens: floral arrangements, princess pine, moss & lichens, cattail tops, etc. • Christmas ornaments: boughs & branches, wreaths, cones, Christmas trees, etc. • Wild edibles: nuts, fruits, blue berries, leaves: spruce tip tea, mushrooms, chaga tea, devils club root, birch sap & syrup, fiddleheads, spices (sage), spruce gum, cattail root, wild rice, high & low bush berries, straw & raspberries, dandelion greens, • Medicinal: chaga, devils club root, yarrow, Labrador tea, rose hip tea, birch sap, elixirs, extracts & tinctures, etc. • Transplants: wild shrubs, ground cover, ferns, flowers, landscaping, etc. • Crafts: birch bark, birch sticks, birch sections, wood cookies, hiking sticks, twig wreaths, buttons, rings, basket materials, cones, bird houses & feeders, grasses, willow roots & twigs, artists conk, wintergreen berry & leaf, spruce roots, rose hips, cattail tops & down, alder cones, spruce cones, etc. -

Gathering Birch and Birch Bark

Birch and Birch Bark by John Zasada, USDA Forest Service All species of trees that we most commonly think of as "timber species" have potential commodity values, often referred to as non-timber forest products (NTFP) or special forest products, that are not necessarily related to wood and fiber products. Some of these NTFP values are recognized and commercially important and others are secreted in the history of Native Americans and other people who at one time in their past depended on natural products for their physical and spiritual well-being. Paper birch is one example of a species that was an important part of Native American culture and has considerable potential for NTFP. Before discussing NTFP from birch, we need to consider the potential for multiple products from this tree and from birch forests. The diagram below illustrates the potential product available from a birch stand as it develops through time. Admittedly, this is an idealized view of the potential. However, there are examples of uses of birch for each of the products indicated in the diagram. There has never been a plan to attempt to harvest all of these products from birch trees and stands in the same geographic area. Northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan would provide a good area to test these ideas. The two main products harvested from birch without killing the tree are sap and bark and, to a very minor extent, the roots. The method of collecting birch sap is generally similar to that of maple. Birch sap differs significantly, however, from maple in that it has simple sugars (glucose and fructose) rather than the more complex sugars of maple (sucrose). -

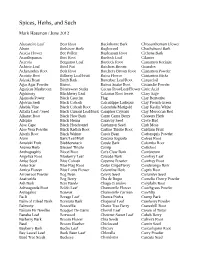

Spices, Herbs, and Such

Spices, Herbs, and Such Mark Hassman / June 2013 Abacateiro Leaf Bear Root Buckthorne Bark Chrysanthemum Flower Abuto Bedstraw Herb Bugleweed Chuchuhuasi Bark Acacia Flower Bee Pollen Bupleurum Root Cichona Bark Acanthopanax Beet Root Burdock Leaf Cilantro Acerola Bergamot Leaf Burdock Root Cinnamon Korinjte Achiote Leaf Betel Nut Butchers Broom Granules Achyranthes Root Beth Root Butcher's Broom Root Cinnamon Powder Aconite Root Bilberry Leaf/Fruit Butea Flower Cinnamon Sticks Adzuki Bean Birch Bark Butterbur Leaf/Root Cinquefoil Agar Agar Powder Bistort Button Snake Root Cistanche Powder Agaricus Mushroom Bittersweet Stalks Cactus Root/Leaf/Flower Citric Acid Agrimony Blackberry Leaf Calamus Root Sweet Clary Sage Ajamoda Power Black Catechu Flag Clay Bentonite Ajowan Seek Black Cohosh Calcatrippe Larkspur Clay French Green Akebia Vine Black Cohosh Root Calendula Marigold Clay Kaolin White Alfalfa Leaf / Seed Black Currant Leaf/Bark Camphor Crystals Clay Moroccan Red Alkanet Root Black Haw Bark Camu Camu Berry Cleavers Herb Allspice Black Henna Caraway Seed Clove Bud Aloe Cape Black Horehound Cardamon Seed Club Moss Aloe Vera Powder Black Radish Root Carline Thistle Root Cnidium Fruit Alteris Root Black Walnut Carob Bean Codonopsis Powder Alum Bark/Leaf/Hull Cascara Sagrada Coleus Root Amalaki Fruit Bladderwrack Cassie Bark Colombo Root Anamu Herb Blessed Thistle Catnip Coltsfoot Andrographis Blood Root Cat's Claw Bark Combretum Angelica Root Blueberry Leaf Catuaba Bark Comfrey Leaf Anise Seed Blue Cohosh Cayenne Powder Comfrey Root Anise -

Non-Traditional Forest Products Directory Is Produced By

NNoonn--TTrraaddiittiioonnaall Forest Forest Products Products Directory Directory Table of Contents Table of Contents...................................................................................................................1 Foreword................................................................................................................................2 Table Explanations.................................................................................................................3 Business Information Tables..................................................................................................4 Products Purchased Table......................................................................................................15 Products Sold Table ...............................................................................................................16 Appendix................................................................................................................................17 Harvesting Boughs.........................................................................................17 Harvesting Birch Bark...................................................................................18 Harvesting Princess Pine...............................................................................21 Wisconsin State Forest Directory ..................................................................23 Wisconsin County Forest Administrators Directory......................................24 This Non-Traditional -

Cork-Containing Barks—A Review

REVIEW published: 19 January 2017 doi: 10.3389/fmats.2016.00063 Cork-Containing Barks—A Review Carla Leite* and Helena Pereira Centro de Estudos Florestais, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal Tree barks are among the less studied forest products notwithstanding their relevant physiological and protective role in tree functioning. The large diversity in structure and chemical composition of barks makes them a particularly interesting potential source of chemicals and bioproducts, at present valued in the context of biorefineries. One of the valuable components of barks is cork (phellem in anatomy) due to a rather unique set of properties and composition. Cork from the cork oak (Quercus suber) has been exten- sively studied, mostly because of its economic importance and worldwide utilization of cork products. However, several other species have barks with substantial cork amounts that may constitute additional resources for cork-based bioproducts. This paper makes a review of the tree species that have barks with significant proportion of cork and on the available information regarding the structural and chemical characterization of their bark. A general integrative appraisal of the formation and types of barks and of cork development is also given. The knowledge gaps and the potential interesting research lines are identified and discussed, as well as the utilization perspectives. Keywords: cork, Quercus suber L., bark, periderm, rhytidome, phellem, suberin Edited by: Pellegrino Musto, National Research Council, Italy INTRODUCTION Reviewed by: Ernesto Di Maio, Trees are externally covered on their stems and branches by the bark that represents 9 to 15% of University of Naples Federico II, the stem volume (Harkin and Rowe, 1971).