Converts to Colonizers?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twilight of the Idols

Jpost | Print Article Page 1 of 2 August 31, 2011 Wednesday 1 Elul 5771 11:34 IST Twilight of the Idols By EMMANUEL NAVON 19/06/2011 Israel’s intellectual elite has been living off the same tired mantras for decades: the occupation is the source of all evil; religion is for retards; the advent of peace depends on Israel alone. At least some of them at last seem to be waking up to the dangers of idolizing false constructs. Photo by: Courtesy Israel’s intellectuals are worried. The Israeli Holy Trinity (Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua, and David Grossman) is getting old. The Hebrew University’s Pantheon (Martin Buber, Yehuda Magnes, and Yeshayahu Leibowitz) belongs in the annals of history. Avraham Burg tries to mimic Leibowitz, but it is hard to inherit the Lithuanian brain box when you didn’t finish college. As for Shlomo Sand, Moshe Zuckermann and Ilan Pappé, only European neo-Marxists are willing to attend their lectures and to publish their books. RELATED: The world's most influential Jews: 31-40 Moshe Zuckermann recently lamented on the lack of interest in intellectuals from mainstream channels. “It used to be that … they would call me from Army Radio,” he said. So what happened? “The people have been silenced. They tried to strangle them – and they’ve succeeded.” Zuckermann doesn’t specify whom he means by “they” but Daniel Gutwein blames “market forces." “You see,” explains Gutwein, “The market … ensures there is no intellectual discussion.” As for Shlomo Sand, he blames the universities themselves: “To become a professor,” he warns, “you have to be cautious.” One only has to look at the political makeup of Israel’s social science faculties to wonder (or, rather, to understand) what Sand means by “cautious.” As for “market forces” being the enemy of intellectual discussion, I bet Bernard Henri-Lévy would beg to differ: he flies a private jet and nonetheless has quite an audience both at home and abroad (including in Israel). -

The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 12-15-2020 The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Gideon Reuveni University of Sussex Diana University Franklin University of Sussex Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reuveni, Gideon, and Diana Franklin, The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism. (2021). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Edited by IDEON EUVENI AND G R DIANA FRANKLIN PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS | WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-711-9 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of librar- ies working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61249-703-7. Cover artwork: Painting by Arnold Daghani from What a Nice World, vol. 1, 185. The work is held in the University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep, Arnold Daghani Collection, SxMs113/2/90. -

ASSOCIATION for JEWISH STUDIES 37TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Hilton Washington, Washington, DC December 18–20, 2005

ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES 37TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Hilton Washington, Washington, DC December 18–20, 2005 Saturday, December 17, 2005, 8:00 PM Farragut WORKS IN PROGRESS GROUP IN MODERN JEWISH STUDIES Co-chairs: Leah Hochman (University of Florida) Adam B. Shear (University of Pittsburgh) Sunday, December 18, 2005 GENERAL BREAKFAST 8:00 AM – 9:30 AM International Ballroom East (Note: By pre-paid reservation only.) REGISTRATION 8:30 AM – 6:00 PM Concourse Foyer AJS ANNUAL BUSINESS MEETING 8:30 AM – 9:30 AM Lincoln East AJS BOARD OF 10:30 AM Cabinet DIRECTORS MEETING BOOK EXHIBIT (List of Exhibitors p. 63) 1:00 PM – 6:30 PM Exhibit Hall Session 1, Sunday, December 18, 2005 9:30 AM – 11:00 AM 1.1 Th oroughbred INSECURITIES AND UNCERTAINTIES IN CONTEMPORARY JEWISH LIFE Chair and Respondent: Leonard Saxe (Brandeis University) Eisav sonei et Ya’akov?: Setting a Historical Context for Catholic- Jewish Relations Forty Years after Nostra Aetate Jerome A. Chanes (Brandeis University) Judeophobia and the New European Extremism: La trahison des clercs 2000–2005 Barry A. Kosmin (Trinity College) Living on the Edge: Understanding Israeli-Jewish Existential Uncertainty Uriel Abulof (Th e Hebrew University of Jerusalem) 1.2 Monroe East JEWISH MUSIC AND DANCE IN THE MODERN ERA: INTERSECTIONS AND DIVERGENCES Chair and Respondent: Hasia R. Diner (New York University) Searching for Sephardic Dance and a Fitting Accompaniment: A Historical and Personal Account Judith Brin Ingber (University of Minnesota) Dancing Jewish Identity in Post–World War II America: -

From Traditional Bilingualism to National Monolingualism 143

140 Hebrew in Ashkenaz HETLMAN, sAMvnL. The People ofthe Book: Drama, Fellowship, and Religion. chicago: chi_ cago University Press, 1983. KArz, JAcoB. Ha-Halakhah ve-ha-Kabbalaft. Jerusalem: Magnes, 19g4. KoWALSKA-GLrKMAN, srEFANrA. "Ludnosc Zydowska warszawy w polowie xIX w. w Swietle Akt Stanu cywilnego." Biuletyn Zydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego 2 (1981): I 18. KUTSCHER, EDUARD. A History of the Hebrew Language. Jerusalem: Magnes, lgg2. LAWRENCE' ELIZABETH. The Origins and Growlh of Modern Education. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970. From Traditional Bilingualism LEvrNSoN, ABRAHAM. Ha-Tenu'ah ha-Ivril ba-Golah (The Hebrew Movement in the Dias_ pora). Warsaw: Brit lvrit Olamit, 1935. to National Monolingualism LTEBERMAN, cHArM. "Legends and rruth About Hassidic printing." yIVo Bletter 34 ( 1 950): t82-208. In Yiddish. ISRAEL BARTAL MARGoLTN, s. Sources and Research on Jewish Industrial Craflsmen. Yol.2. St. petersburg: ORT, 1915. In Russian. MIRoN, oxN. Bodedim be-Mo'adam (when Loners come Together). Tel Aviv: Am oved, t987. RASHDALL, HAsrrNGs. The universities of Europe in the Middle Ages. F. M. powicke and National movements springing up in nineteenth-century Europe associated what A. B. Emden, eds. New edition. Oxford: Oxford University press, 1936. they termed the "National Revival" with a crucial set of features, without which sHoHAT, AzRrEL. "The Cantonists and the 'yeshivot' of Russian Jewry during the Reign of such a revival could not take place. Outstanding among these, along with territory Nicholas I;' Jewish History I ( 1986): 33-8, Hebrew Section. and historical heritage, was the "national tongue." Generally, this "national" SLUTSKY, YEHUDA. The Russian-Jewish Press in the Nineteenth Century. Jerusalem: Mos- tongue was a particular dialect that became the state language and ousted alterna- sad Bialik, 1970. -

The Invention of the Jewish People (Trans. Yael Lotan) by Shlomo Sand

NATIONS AND J OURNAL OF THE ASSOCIATION AS FOR THE STUDY OF ETHNICITY EN NATIONALISM AND NATIONALISM Nations and Nationalism 16 (4), 2010, 774–787. Book Reviews Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People (trans. Yael Lotan). New York: Verso, 2009. 332pp, d18.99 (pbk). In the 1900s, many pro-Westernisation Jews argued that the Jews were a people (volk), but not a nation. Others maintained that the Jewish people was dead and only the Jewish spirit was left. Historically, the drive to ‘‘reinvent’’ the Jewish nation was engendered in reaction to the disintegration it had undergone in the nineteenth century, when Judaism was divided not only into different forms but also into German Jews, French Jews and so forth. Thus, a movement that sought to reconstruct the Jewish identity and experience by employing notions that had become intrinsic to the scholarly and popular dialogue in that century – culture and race – appeared. Shlomo Sand’s book, which has become very popular (though certainly not for its scholarly merits), does not argue that the Jewish people died in the nineteenth century – it argues that it was never born. He claims that only in the 1900s was the Jewish people ‘‘invented’’ by Jewish historians and proto-Zionist and Zionist thinkers, and that this ‘‘invention’’ managed not only to propagate the myth, by various means, but also to establish a state on its basis. Sand does not have to deny the Jews the title nation, because in his counter-history of the Jews he takes a much more radical stand: not only are the Jews not a nation, they were never a people; they never constituted the platform upon which a nation is built, as other peoples created (or invented, as it were) their nationalities in the nineteenth century. -

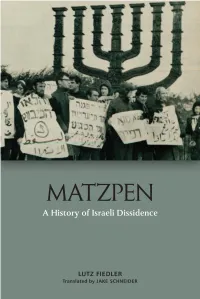

9781474451185 Matzpen Intro

MATZPEN A History of Israeli Dissidence Lutz Fiedler Translated by Jake Schneider 66642_Fiedler.indd642_Fiedler.indd i 331/03/211/03/21 44:35:35 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com Original version © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, 2017 English translation © Jake Schneider, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5116 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5118 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5119 2 (epub) Th e right of Lutz Fiedler to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Originally published in German as Matzpen. Eine andere israelische Geschichte (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017) Th e translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Th yssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Offi ce, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

The Post-Communist Motherlands

Back to the NJ post-Communist motherlands Reflections of a Jerusalemite historian Israel Bartal DOI: 10.30752/nj.86216 Remote celestial stars, celestial stars so close Remote and distant from the watching eye And yet their lights so close to the observer’s heart ‘Remote Celestial Stars’, Jerusalem 1943 (Tchernichovsky 1950: 653), translated by Israel Bartal. Remote and distant, and yet so close All of them, regardless of date or place, have shared similar sentiments regarding their In his last poem, written in a Greek Orthodox old countries. My thesis is that this was the monastery in Jerusalem in the summer of 1943, case not only for the first generation of East the great Hebrew poet Shaul Tchernichovsky European newcomers; many of those born in (1875–1943) eloquently expounded in some Israel (the ‘second generation’) have continued dozens of lines his life experience. Watching the ambivalent attitude towards their coun- the Mediterranean sky, the Ukrainian-born tries of origin, so beautifully alluded to by the Zionist was reminded of his youth under the Hebrew poet, myself included. skies of Taurida, Crimea and Karelia. His self- Historically speaking, Jewish emigrants examination while watching the Israeli sky from Eastern Europe have been until very brought to his mind views, memories, texts and late in the modern era members of an old ideas from the decades he had lived in Eastern ethno-religious group that lived in a diverse Europe. After some twenty years of separa- multi-ethnic environment in two pre-First tion from his home country, the provinces in World War empires. -

Judah David Eisenstein and the First Hebrew Encyclopedia

1 Abstract When an American Jew Produced: Judah David Eisenstein and the First Hebrew Encyclopedia Between 1907 and 1913, Judah David Eisenstein (1854–1956), an amateur scholar and entrepreneurial immigrant to New York City, produced the first modern Hebrew encyclopedia, Ozar Yisrael. The Ozar was in part a traditionalist response to Otsar Hayahdut: Hoveret l’dugma, a sample volume of an encyclopedia created by Asher Ginzberg (Ahad Ha’am)’s circle of cultural nationalists. However, Eisenstein was keen for his encyclopedia to have a veneer of objective and academic respectability. To achieve this, he assembled a global cohort of contributors who transcended religious and ideological boundaries, even as he retained firm editorial control. Through the story of the Ozar Yisrael, this dissertation highlights the role of America as an exporter of Jewish culture, raises questions about the borders between Haskalah and cultural nationalism, and reveals variety among Orthodox thinkers active in Jewish culture in America at the turn of the twentieth century. When an American Jew Produced: Judah David Eisenstein and the First Hebrew Encyclopedia by Asher C. Oser Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Jewish History Bernard Revel Graduate School Yeshiva University August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 by Asher C. Oser iii The Committee for this doctoral dissertation consists of Prof. Jeffrey S. Gurock, PhD, Chairperson, Yeshiva University Prof. Joshua Karlip, PhD, Yeshiva University Prof. David Berger, PhD, Yeshiva University iv Acknowledgments This is a ledger marking debts owed and not a place to discharge them. Some debts are impossible to repay, and most are the result of earlier debts, making it difficult to know where to begin. -

Judaica Olomucensia

Judaica Olomucensia 2015/1 Special Issue Jewish Printing Culture between Brno, Prague and Vienna in the Era of Modernization, 1750–1850 Editor-in-Chief Louise Hecht Editor Matej Grochal This issue was made possible by a grant from Palacký University, project no. IGA_FF_2014_078 Table of Content 4 Introduction Louise Hecht 11 The Lack of Sabbatian Literature: On the Censorship of Jewish Books and the True Nature of Sabbatianism in Moravia and Bohemia Miroslav Dyrčík 30 Christian Printers as Agents of Jewish Modernization? Hebrew Printing Houses in Prague, Brno and Vienna, 1780–1850 Louise Hecht 62 Eighteenth Century Yiddish Prints from Brünn/Brno as Documents of a Language Shift in Moravia Thomas Soxberger 90 Pressing Matters: Jewish vs. Christian Printing in Eighteenth Century Prague Dagmar Hudečková 110 Wolf Pascheles: The Family Treasure Box of Jewish Knowledge Kerstin Mayerhofer and Magdaléna Farnesi 136 Table of Images 2015/1 – 3 Introduction Louise Hecht Jewish Printing Culture between Brno, Prague and Vienna in the Era of Modernization, 1750–1850 The history of Jewish print and booklore has recently turned into a trendy research topic. Whereas the topic was practically non-existent two decades ago, at the last World Congress of Jewish Studies, the “Olympics” of Jewish scholarship, held in Jerusalem in August 2013, various panels were dedicated to this burgeoning field. Although the Jewish people are usually dubbed “the people of the book,” in traditional Jewish society authority is primarily based on oral transmission in the teacher-student dialog.1 Thus, the innovation and modernization process connected to print and subsequent changes in reading culture had for a long time been underrated.2 Just as in Christian society, the establishment of printing houses and the dissemination of books instigated far-reaching changes in all areas of Jewish intellectual life and finally led to the democratization of Jewish culture.3 In central Europe, the rise of publications in the Jewish vernacular, i.e. -

An Ethical Critique of the United States-Israel Alliance Reviving the Prophetic Tasks of Remembrance and Critique of Power Daniel C

An Ethical Critique of the United States-Israel Alliance Reviving the Prophetic Tasks of Remembrance and Critique of Power Daniel C. Maguire Daniel C. Maguire is a professor of moral theology at Marquette University, a Catholic, Jesuit Institution, and past president of The Society of Christian Ethics. He is the author of The Horrors We Bless: Rethinking the Just-War Legacy (Fortress Press, 2007). He who controls the past, controls the future; and he who controls the present, controls the past. –George Orwell War is the coward’s escape from the problems of peace. –Robert MacAfee Brown You cannot like the word, but what is happening is an occupation—to hold 3.5 million Palestinians under occupation. I believe that is a terrible thing for Israel and for the Palestinians… It can’t continue endlessly. –Prime Minister of Israel Ariel Sharon Political language…is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. –George Orwell In no field has the pursuit of truth been more difficult than that of military history. –Military historian Sir B. H. Liddell Hart Whenever they burn books they will also, in the end, burn human beings. –German philosopher Heinrich Heine History sneaks up on the powerful. –Professor of Jewish Studies Marc Ellis In 1887, in a speech at the Sorbonne, Ernest Renan observed that “forgetting” is “a crucial factor in the creation of a nation.”[1] In creating a national unifying narrative, certain difficult memories of unseemly events have to be erased. As Renan said, this will even include the wholesale slaughter of certain ethnic and religious groups within the claimed national borders.[2] This violence must be whitewashed off the screen of public consciousness. -

List of Publications Books (As Author) 1) Haskalah and History, The

List of Publications Books (as author) 1) Haskalah and History, The Emergence of a Modern Jewish Awareness of the Past, Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center, 1995 (second edition, 2011) (Hebrew). 2) Haskalah and History, The Emergence of a Modern historical Consciousness. London and Portland OR., The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2001 3) Maàpechat ha-Neorut, The Jewish Enlightenment in the 18th Century. Jerusalem: The Shazar Center, 2002 (second edition, 2011) (Hebrew) 4) The Jewish Enlightenment, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press 2004. 5) Moses Mendelssohn, Biography, Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center, 2005 (three editions) (Hebrew) 6) Haskala - Jüdische Aufklärung. Geschichte einer kulturellen Revolution, Hildesheim, Zürich, New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 2007 7) Moses Mendelssohn, Ein jüdischer Denker in der Zeit der Aufklärung. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009 8) The Origins of Jewish Secularization in 18th Century Europe, Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center, 2010 (second edition, 2011) (Hebrew). 9) Moses Mendelssohn, Sage of Modernity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010. 10) The Jewish Enlightenment in the 19th Century, Jerusalem: Carmel Publication, 2010 (second edition, 2011) (Hebrew). 11) The Origins of Jewish Secularization in 18th Century Europe, Phildelphia and Oxford: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. 12) (with Natalie Naimark-Goldberg), Cultural Revolution in Berlin: Jews in the age of Enlightenment. Oxford: The Bodleian Library and the Journal of Jewish Studies, 2011. 13) 摩西‧孟德爾松:啟蒙時代的猶太思想家, Moses Mendelssohn, Pioneer of Jewish Modernity, Chinese edition, Taipei, Taiwan: Showwe Information Co., 2014. Books (as editor) 13) S.J. Fuenn - From Militant to Conservative Maskil. The Dinur Center: Jerusalem 1993 (Hebrew). 14) Sefer Hamatsref, An Unknown Maskilic Critic of Jewish Society in Russia in the 19th Century, Jerusalem: The Bialik Institue 1998 (Hebrew). -

Enzyklopädie Jüdischer Geschichte Und Kultur

Enzyklopädie jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur Gesamtwerk in 7 Bänden inkl. Registerband Bearbeitet von Dan Diner 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. 4200 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 476 02500 5 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Geschichte > Kultur- und Ideengeschichte schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. EJGK Enzyklopädie jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur Leseprobe Inhalt 2–3 Die EJGK 4–5 Autorenverzeichnis 6–17 Einführung 18–21 Artikelverzeichnis 22–47 Ausgewählte Artikel 48 Bestellmöglichkeit 49 Impressum EJGK Enzyklopädie jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur 2 Neuer Blick auf die jüdische Geschichte und Kultur ... Von Europa über Amerika bis zum Vorderen Orient, Nordafrika und anderen außer - europäischen jüdischen Siedlungsräumen erschließt die Enzyklopädie in sechs Bänden und einem Registerband die neuere Geschichte der Juden von 1750 bis 1950. Rund 800 Stichwörter präsentieren den Stand der internationalen Forschung und entwerfen ein viel schichtiges Porträt jüdischer Lebenswelten – illustriert durch viele Karten und Abbildungen. Übergreifende Informationen zu zentralen Themen vermitteln ca. 40 Schlüssel artikel zu Begriffen wie Autonomie, Exil, Emanzipation, Literatur, Liturgie, Musik oder Wissenschaft des Judentums. Zuverlässige Orientierung bei der Arbeit mit dem Nachschlagewerk bieten ausführliche Personen-, Orts- und Sachregister im siebten Band. Die Enzyklopädie stellt Wissen in einen Gesamtkontext und bietet Wissenschaftlern und Interessierten neue Einblicke in die jüdische Geschichte und Kultur. Ein herausragender Beitrag zum Verständnis des Judentums und der Moderne.