Palestine Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twilight of the Idols

Jpost | Print Article Page 1 of 2 August 31, 2011 Wednesday 1 Elul 5771 11:34 IST Twilight of the Idols By EMMANUEL NAVON 19/06/2011 Israel’s intellectual elite has been living off the same tired mantras for decades: the occupation is the source of all evil; religion is for retards; the advent of peace depends on Israel alone. At least some of them at last seem to be waking up to the dangers of idolizing false constructs. Photo by: Courtesy Israel’s intellectuals are worried. The Israeli Holy Trinity (Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua, and David Grossman) is getting old. The Hebrew University’s Pantheon (Martin Buber, Yehuda Magnes, and Yeshayahu Leibowitz) belongs in the annals of history. Avraham Burg tries to mimic Leibowitz, but it is hard to inherit the Lithuanian brain box when you didn’t finish college. As for Shlomo Sand, Moshe Zuckermann and Ilan Pappé, only European neo-Marxists are willing to attend their lectures and to publish their books. RELATED: The world's most influential Jews: 31-40 Moshe Zuckermann recently lamented on the lack of interest in intellectuals from mainstream channels. “It used to be that … they would call me from Army Radio,” he said. So what happened? “The people have been silenced. They tried to strangle them – and they’ve succeeded.” Zuckermann doesn’t specify whom he means by “they” but Daniel Gutwein blames “market forces." “You see,” explains Gutwein, “The market … ensures there is no intellectual discussion.” As for Shlomo Sand, he blames the universities themselves: “To become a professor,” he warns, “you have to be cautious.” One only has to look at the political makeup of Israel’s social science faculties to wonder (or, rather, to understand) what Sand means by “cautious.” As for “market forces” being the enemy of intellectual discussion, I bet Bernard Henri-Lévy would beg to differ: he flies a private jet and nonetheless has quite an audience both at home and abroad (including in Israel). -

The Invention of the Jewish People (Trans. Yael Lotan) by Shlomo Sand

NATIONS AND J OURNAL OF THE ASSOCIATION AS FOR THE STUDY OF ETHNICITY EN NATIONALISM AND NATIONALISM Nations and Nationalism 16 (4), 2010, 774–787. Book Reviews Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People (trans. Yael Lotan). New York: Verso, 2009. 332pp, d18.99 (pbk). In the 1900s, many pro-Westernisation Jews argued that the Jews were a people (volk), but not a nation. Others maintained that the Jewish people was dead and only the Jewish spirit was left. Historically, the drive to ‘‘reinvent’’ the Jewish nation was engendered in reaction to the disintegration it had undergone in the nineteenth century, when Judaism was divided not only into different forms but also into German Jews, French Jews and so forth. Thus, a movement that sought to reconstruct the Jewish identity and experience by employing notions that had become intrinsic to the scholarly and popular dialogue in that century – culture and race – appeared. Shlomo Sand’s book, which has become very popular (though certainly not for its scholarly merits), does not argue that the Jewish people died in the nineteenth century – it argues that it was never born. He claims that only in the 1900s was the Jewish people ‘‘invented’’ by Jewish historians and proto-Zionist and Zionist thinkers, and that this ‘‘invention’’ managed not only to propagate the myth, by various means, but also to establish a state on its basis. Sand does not have to deny the Jews the title nation, because in his counter-history of the Jews he takes a much more radical stand: not only are the Jews not a nation, they were never a people; they never constituted the platform upon which a nation is built, as other peoples created (or invented, as it were) their nationalities in the nineteenth century. -

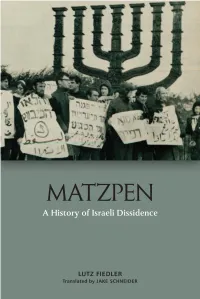

9781474451185 Matzpen Intro

MATZPEN A History of Israeli Dissidence Lutz Fiedler Translated by Jake Schneider 66642_Fiedler.indd642_Fiedler.indd i 331/03/211/03/21 44:35:35 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com Original version © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, 2017 English translation © Jake Schneider, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5116 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5118 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5119 2 (epub) Th e right of Lutz Fiedler to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Originally published in German as Matzpen. Eine andere israelische Geschichte (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017) Th e translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Th yssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Offi ce, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

An Ethical Critique of the United States-Israel Alliance Reviving the Prophetic Tasks of Remembrance and Critique of Power Daniel C

An Ethical Critique of the United States-Israel Alliance Reviving the Prophetic Tasks of Remembrance and Critique of Power Daniel C. Maguire Daniel C. Maguire is a professor of moral theology at Marquette University, a Catholic, Jesuit Institution, and past president of The Society of Christian Ethics. He is the author of The Horrors We Bless: Rethinking the Just-War Legacy (Fortress Press, 2007). He who controls the past, controls the future; and he who controls the present, controls the past. –George Orwell War is the coward’s escape from the problems of peace. –Robert MacAfee Brown You cannot like the word, but what is happening is an occupation—to hold 3.5 million Palestinians under occupation. I believe that is a terrible thing for Israel and for the Palestinians… It can’t continue endlessly. –Prime Minister of Israel Ariel Sharon Political language…is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. –George Orwell In no field has the pursuit of truth been more difficult than that of military history. –Military historian Sir B. H. Liddell Hart Whenever they burn books they will also, in the end, burn human beings. –German philosopher Heinrich Heine History sneaks up on the powerful. –Professor of Jewish Studies Marc Ellis In 1887, in a speech at the Sorbonne, Ernest Renan observed that “forgetting” is “a crucial factor in the creation of a nation.”[1] In creating a national unifying narrative, certain difficult memories of unseemly events have to be erased. As Renan said, this will even include the wholesale slaughter of certain ethnic and religious groups within the claimed national borders.[2] This violence must be whitewashed off the screen of public consciousness. -

Converts to Colonizers?

review Shlomo Sand, Matai ve’ech humtza ha’am hayehudi? [When and How Was the Jewish People Invented?] Resling: Tel Aviv 2008, 94 nis, paperback 358 pp, 1005 8 500 00309 0 Gabriel Piterberg CONVERTS TO COLONIZERS? The foundational myths of the state of Israel rest on the notion that, through- out history, the Jews have been descended from a single ethno-biological core of Judean exiles who had been removed from their ancestral lands in the first two centuries ce. Shlomo Sand’s When and How Was the Jewish People Invented? sets out to refute such claims of organic ethnic continuity, arguing that the idea that the Jews had been exiled across the Mediterranean world was a creation of the Christian Church—mass displacement as punishment and constant reminder of who is Israel Veritas—which was con- veniently embraced by 19th-century Jewish scholars. Their narratives of a centuries-long Galut, ‘exile’, and by extension the Zionist project of ‘return- ing’ to reclaim ancient territories, are based on historical fictions. Against these, Sand offers an alternative history in which the strik- ing demographic growth of the Jews in the Hellenistic Mediterranean was the product not of mass exile, but of an energetic drive of proselytism and conversion that had begun under the Hasmonean Kingdom in the second century bce and lasted till the fourth century ce. Conversions were also, Sand holds, the source of the large Jewish populations at the margins of the Hellenistic world—Arabia, North Africa and the area between the Black and Caspian Seas—as Judaizing currents met repression in Christian territories and fanned out into the largely pagan lands beyond. -

The Invention of the Jewish People

Published on Reviews in History (https://reviews.history.ac.uk) The Invention of the Jewish People Review Number: 973 Publish date: Friday, 1 October, 2010 Author: Shlomo Sand ISBN: 9781844674220 Date of Publication: 2009 Price: £18.99 Pages: 332pp. Publisher: Verso Place of Publication: London Reviewer: Michael Berkowitz Shlomo Sand’s The Invention of the Jewish People, which appeared in Hebrew as Matai ve’ekh humtza ha’am hayehudi? [When and How Was the Jewish People Invented?] (1) elicited a thunderous response that has yet to abate. Beginning with an interesting and very personal introduction, Sand proceeds to engage, chronologically, the thought of Jews about their own character as a ‘people,’ ‘nation,’ and occasionally, ‘race’ (sic), largely by examining the published writings of figures known to scholars in Jewish Studies, but less familiar to historians generally – including Josephus, Isaak Markus Jost, Heinrich Graetz, Simon Dubnow, Yitzhak Baer, Ben-Zion Dinur, Hans Kohn, and Salo Baron. Sand’s preface to the English language edition states that ‘the disparity between what my research suggested about the history of the Jewish people and the way that history is commonly understood – not only within Israel but in the larger world – shocked me as it shocked my [Hebrew] readers’ (p. xi). Sand insinuates that this ‘shock’ accounts for the excitement surrounding the book – which is a more reasonable assessment regarding its reception in Israel than in the English-speaking world. To his credit, Sand admits that there is almost nothing original in his work, as it is mainly a synthesis and counter-narrative. He writes that ‘I found myself being shaken repeatedly as I worked on the composition’ of the book. -

Shlomo Sand: the Invention of the Jewish People (2009)

The Invention of the Jewish People The Invention of the Jewish People Shlomo Sand Translated by Yael Lotan VERSO London • New York English edition published by Verso 2009 © Verso 2009 Translation © Yael Lotan First published as Matai ve'ekh humtza ha'am hayehudi? [When and How Was the Jewish People Invented?] © Resling 2008 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-422-0 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh Printed in the US by Maple Vail To the memory of the refugees who reached this soil and those who were forced to leave it. Contents PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION ÎX INTRODUCTION: BURDENS OF MEMORY 1 Identity in Movement 1 Constructed Memories 14 1. MAKING NATIONS: SOVEREIGNTY AND EQUALITY 23 Lexicon: "People" and Ethnos 24 The Nation: Boundaries and Definitions 31 From Ideology to Identity 39 From Ethnic Myth to Civil Imaginary 45 The Intellectual as the Nations "Prince" 54 2. MYTHISTORY: IN THE BEGINNING, GOD CREATED THE PEOPLE 64 The Early Shaping of Jewish History 65 The Old Testament as Mythistory 71 Race and Nation 78 A Historians' Dispute 81 A Protonationalist View from the East 87 An Ethnicist Stage in the West 95 The First Steps of Historiography in Zion 100 Politics and Archaeology 107 The Earth Rebels against Mythistory 115 The Bible as Metaphor 123 3. -

Marc Lenot Disillusionment: Vilém Flusser and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

FLUSSER STUDIES 26 Marc Lenot Disillusionment: Vilém Flusser and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict In the context of Vilém Flusser’s relationship with Judaism and with his own Jewish- ness―to which the present issue of Flusser Studies is devoted―this essay presents a dozen texts written by Flusser about Israel and the conflict with the Palestinians (together with a few letters by him on this subject). Without taking sides on such a delicate subject, it at- tempts to shed light on Flusser's view of Israel. Other essays in this issue evoke Flusser’s “essential” relationship with Israel; here, we attempt only to set forth his political view (even even though the two are inseparable). According to a recent biography, the teenage Flusser adhered to Zionist ideas (Bernar- do / Guldin: 289) but soon turned his back on this ideology, perhaps―though this is only a hypothesis―after discussions with his father, a well-integrated agnostic Jew who in 1938 refused to make his Aliya, which would have allowed him to become a professor at the University of Jerusalem (and would, in retrospect, have saved his life). Or perhaps, as sug- gested by Bernardo and Guldin (Ibid.), it was a consequence of his flight from Prague at the time of the Nazis invasion, though the causal connection is not clear. Admittedly, Flusser was always proud of his Jewish origins, and of his Jewish culture in particu- lar. However, particularly during the first of his two trips to Israel (from April 28 to May 21, 1980), he developed an original reflection on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the dead-end of Zionism. -

The Anti-Zionism of Brian Klug, Jaqueline Rose Et Al.: Ignorance Or Ideology?

1 Evyatar Friesel The anti-Zionism of Brian Klug, Jaqueline Rose et al.: ignorance or ideology? “But fundamentally, it [Zionism] is the stepchild of anti-Semitism.” – Brian Klug, 2007. “My first visit to Israel in 1980 was hardly typical for a young Jewish woman. On the plane, I found myself sitting next to Dima Habash, 16-year-old niece of George Habash, the leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. 'Are you Jewish?' she asked, and when I said I was, without a moment's pause she continued: 'You think Israel belongs to you.' 'No,' I replied, surprised by my own urgency, 'I think it belongs to you.'” - Jacqueline Rose, 2002. “… the historical myths that were once, with the aid of a good deal of imagination, able to create Israeli society are now powerful forces helping to raise the possibility of its destruction." – Shlomo Sand, 2012. “Israel, in short, is an anachronism.” – Tony Judt, 2003. 1 Differently from Tony Judt, who as a respected historian should not have indulged in hip-shooting, Jacqueline Rose touched from the start the core issue: the legitimacy of the Jewish state. The debate on Palestine resembles an inverted pyramid: the myriad of arguments and allegations – the reasons for the Jewish immigration to the country, the causes and the results of the war in 1948, the situation of the Arab refugees, Israel in the Middle East, who did what to whom, the possible solutions of the conflict - they all depend on that one point at the inverted bottom of the pyramid, namely, the position regarding to who has the “right” to Palestine, or more exactly, the question of Jewish right. -

1 Haaretz20160813 Israel Isn't Fascist, but It Still Needs the World to Save It

Haaretz20160813 Israel isn’t fascist, but it still needs the world to save it from itself By Shlomo Sand http://www.haaretz.com/misc/article-print-page/.premium-1.736660 We are in a dangerous situation that can deteriorate into the expulsion of some of the residents of the territories, and even, in the face of serious armed resistance, into acts of mass slaughter. In recent months we’ve witnessed a cascade of articles and calls for help by all sorts of learned people on the liberal left crying out that fascism is threatening Israel. Some of them claim that it’s already here; others warn that it’s about to arrive. Facing them are others a bit less leftist and a bit less liberal who claim that none of this is true. Israel is a stable democracy that to defend itself from terrorism and regional threats sometimes commits inhumane acts. But other democratic countries have acted similarly during periods of conflict. During the Cold War, McCarthyism spread in the United States and devoured the world’s most stable liberal democracy. During the war in Algeria, the French government was very intolerant toward the supporters of an independent Algeria (professors and teachers were fired), not to mention the brutal policy against the freedom fighters themselves. On October 17, 1961, the French police killed 100 to 200 nonviolent Arab demonstrators in the heart of Paris with hardly a response by the press. It’s hard to imagine such an event in Tel Aviv today. I must reiterate: Analogy is the mother of all human wisdom. -

WORD: in MEMORY of a VILLAGE 259 Forgetting the Land 260 a Land of Forgetting 271 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 283 INDEX 285

The Invention of the Land of Israel From Holy Land to Homeland Shlomo Sand (2012) Translated by Jeremy Forman In memory of the villagers of al-Sheikh Muwannis, who were uprooted long ago from the place where I now live and work Contents INTRODUCTION: BANAL MURDER AND TOPONYMY 1 Memories from an Ancestral Land 1 Rights to an Ancestral Land 10 Names of an Ancestral Land 22 1. MAKING HOMELANDS: BIOLOGICAL IMPERATIVE OR NATIONAL PROPERTY? 31 The Homeland—A Natural Living Space? 33 Place of Birth or Civil Community? 39 Territorialization of the National Entity 53 Borders as Boundaries of Spatial Property 6 0 2. MYTHERRITORY: IN THE BEGINNING, GOD PROMISED THE LAND 67 Gifted Theologians Bestow a Land upon Themselves 68 From the Land of Canaan to the Land of Judea 86 The Land of Israel in Jewish Religious Legal Literature 102 ''Diaspora' and Yearning for the Holy Land 107 3. TOWARD A CHRISTIAN ZIONISM: AND BALFOUR PROMISED THE LAND 119 Pilgrimage after the Destruction: A Jewish Ritual? 121 Sacred Geography and Journeys in the Land of Jesus 132 From Puritan Reformation to Evangelicalism 141 Protestants and the Colonization of the Middle East 156 4. ZIONISM VERSUS JUDAISM: THE CONQUEST OF "ETHNIC" SPACE 177 Judaism's Response to the Invention of the Homeland 179 Historical Right and the Ownership of Territory 196 Zionist Geopolitics and the Redemption of the Land 214 From Internal Settlement to External Colonization 230 5. CONCLUSION: THE SAD TALE OF THE FROG AND THE SCORPION 255 AFTERWORD: IN MEMORY OF A VILLAGE 259 Forgetting the Land 260 A Land of Forgetting 271 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 283 INDEX 285 Flyleaf What is a homeland and when does it become a national territory? Why have so many people been killing to die for such places throughout the twentieth century? What is the essence of the Promised Land? Following the acclaimed and controversial The Invention of the Jewish People, Shlomo Sand examines the mystenous sacred land that has become the site of the longest running national struggle of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. -

Study of the Zionist Metamorphosis of the Jewish Masculine Body and the Birth of the “Muscle Jew”

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 16, Issue 5 (Sep. - Oct. 2013), PP 85-91 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Evolutionary Aesthetics and the Hebrew Male Body: Study of the Zionist metamorphosis of the Jewish masculine body and the birth of the “muscle Jew” Yosra Amraoui Abstract: The ancient history of the Jewish people testifies of many a reference to forced exiles imposed on the Jews resulting in a centuries-long journey of wandering and persecution that culminated in the Nazi Holocaust of the 20th century. It is argued by theorists of the body that this history of non-resistance on the part of the Jews affected the physiognomy of the Jewish male in such a tremendous manner that physically transformed the stature of the Jew into one that is frail, short-sized and pale. It was not until the late 19th century that the Jewish thinker Max Nordau (co-founder of the World Zionist Organization and close friend to Theodor Herzl) introduced the image of the “muscle Jew” at the Second Zionist Congress held in 1898 as an idealistic aspiration necessary to the realization of the Zionist scheme. “Muscular Judaism” then evolved into a body of studies and theories that examined the role of history and collective memory in the physical “regeneration” of the male Jewish body into one that is militarily fit to fight for self reaffirmation. This paper purposefully introduces the background of this body of theories and literature and frames it within the field of evolutionary aesthetics for a better demonstration of the journey accompanying the metamorphosis of the male Jewish body for Zionist and political ends.