Season 2014-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Dissertation Document

Abstract Title of Dissertation: INFLUENCES AND TRANSFORMATIONS: 19TH- CENTURY SOLO AND COLLABORATIVE PIANO REPERTOIRE Miori Sugiyama, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2012 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music, Piano Division This dissertation is an exploration of the inter-relationships of genres in the collaborative piano repertoire, particularly in music of the 19th century, an especially important period for collaborative piano repertoire. During this time, much of the repertoire gave equal importance to the piano in duo and ensemble repertoire. Starting with Schubert, and becoming more apparent with the development of the German lied, the piano became a more integral part of any composition, the piano part being no longer simplistic but rather a collaborative partner with its own voice. Mendelssohn transformed the genre of lieder by writing them, without their words, for solo piano. In addition to creating some of the greatest and most representative lieder in the Romantic period, composers such as Schumann, Brahms, and Strauss continued the evolution of the sonata by writing works that were more technically demanding on the performer, musically innovative, and structurally still evolving. In the case of Chopin who wrote mostly piano works, a major influence came from the world of opera, particularly the Bel Canto style. In exploring two specific genres, vocal and instrumental piano works by these composers; it is fascinating to see how one genre translates to another genre. This was especially true in the vocal and instrumental works by Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Chopin, and Strauss. All of these composers, with the exception of Chopin, contributed equally to both the song and sonata genres. -

Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 1 year for only $29.99* *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. Subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com, or send a check or money order to: Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480 Be sure to include your name, mailing address, and email address! If you have any questions about subscribing, you can contact us at [email protected] or visit us online! Cover Photography © Garry Rollins Issue 67 Fall 2019 Welcome to Galaxy’s Edge: 64 A Travellers Guide to Batuu Contents Disney News ............................................................................ 8 Calendar of Events ...........................................................17 The Spooky Side MOUSE VIEWS .........................................................19 74 Guide to the Magic of Walt Disney World by Tim Foster...........................................................................20 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................24 Shutters and Lenses by Mike Billick .........................................................................26 Travel Tips Grrrr! 82 by Michael Renfrow ............................................................36 Hangin’ With the Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................38 Bears of Disney Disney Cuisine by Erik Johnson ....................................................................40 -

CHAN 6659(4) CHAN 6659 BOOK.Qxd 22/5/07 4:12 Pm Page 2

CHAN 6659 Cover.qxd 22/5/07 4:08 pm Page 1 CHAN 6659(4) CHAN 6659 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 4:12 pm Page 2 Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) Sonata No. 2 in D major, Op. 94a 23:52 5 I Moderato 8:10 COMPACT DISC ONE 6 II Presto 4:40 Sonata No. 1 in G major, Op. 78 29:26 7 III Andante 3:50 1 I Vivace ma non troppo 11:14 8 IV Allegro con brio 7:02 2 II Adagio 8:51 TT 53:34 3 III Allegro molto moderato 9:16 COMPACT DISC THREE Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 100 20:24 Franz Schubert (1797–1828) 4 I Allegro amabile 8:23 5 II Andante tranquillo – Vivace 6:37 Sonata in A major for Violin and Piano, 6 III Allegretto grazioso (quasi andante) 5:21 Op. post. 162 D574 21:43 1 I Allegro moderato 8:21 Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 108 21:41 2 II Scherzo and Trio 4:04 7 I Allegro 8:29 3 III Andantino 4:13 8 II Adagio 4:33 4 IV Allegro vivace 4:58 9 III Un poco presto e con sentimento 2:46 10 IV Presto agitato 5:39 5 Fantasie in C major for Violin and Piano, TT 71:44 Op. post. 159 D934 25:41 COMPACT DISC TWO Sergey Sergeyevich Prokofiev (1891–1953) Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 80 29:31 Sonata in E flat major, Op. 18 32:02 1 I Andante assai 7:01 6 I Allegro ma non troppo 12:24 2 II Allegro brusco 7:01 7 II Improvisation. -

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos For

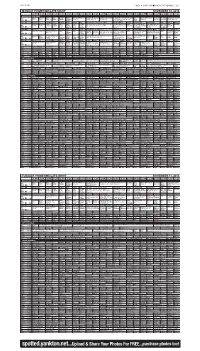

PAGE 10B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2014 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Arthur Å Wild Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Ice Warriors -- USA Sled Hockey BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS (DVS) (DVS) Kratts Å Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Miami Beach” Å “Madison” Å The U.S. sled hockey team. (In World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Miami Beach” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å (DVS) News Å KTIV $ 4 $ Queen Latifah Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent The Voice The artists perform. (N) Å The Blacklist (N) News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Voice “The Live Playoffs, Night 1” The art- The Blacklist Red and KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å (N) Å Judy (N) Judy (N) News Nightly News Bang ists perform. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å Berlin head to Moscow. News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % Å Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory (N) Å (In Stereo) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

EXCLUSIVE 2019 International Pizza Expo BUYERS LIST

EXCLUSIVE 2019 International Pizza Expo BUYERS LIST 1 COMPANY BUSINESS UNITS $1 SLICE NY PIZZA LAS VEGAS NV Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 $5 PIZZA ANDOVER MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 $5 PIZZA MINNEAPOLIS MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 $5 PIZZA BLAINE MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 1000 Degrees Pizza MIDVALE UT Franchise 1 137 VENTURES SAN FRANCISCO CA OTHER 137 VENTURES SAN FRANCISCO, CA CA OTHER 161 STREET PIZZERIA LOS ANGELES CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 2 BROS. PIZZA EASLEY SC Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 2 Guys Pies YUCCA VALLEY CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 203LOCAL FAIRFIELD CT Independent (Less than 9 locations) No response 247 MOBILE KITCHENS INC VISALIA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 25 DEGREES HB HUNTINGTON BEACH CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 26TH STREET PIZZA AND MORE ERIE PA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 290 WINE CASTLE JOHNSON CITY TX Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 3 BROTHERS PIZZA LOWELL MI Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3.99 Pizza Co 3 Inc. COVINA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3010 HOSPITALITY SAN DIEGO CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 307Pizza CODY WY Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 32KJ6VGH MADISON HEIGHTS MI Franchise 2-5 360 PAYMENTS CAMPBELL CA OTHER 399 Pizza Co WEST COVINA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 399 Pizza Co MONTCLAIR CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3G CAPITAL INVESTMENTS, LLC. ENGLEWOOD NJ Not Yet in Business 3L LLC MORGANTOWN WV Independent (Less than 9 locations) 6-9 414 Pub -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

2019 National Sports and Entertainment History Bee Round 2

Sports and Entertainment Bee 2018-2019 Prelims 2 Prelims 2 Regulation (Tossup 1) This man stars in an oft-parodied commercial in which he states \Ballgame" before taking a drink of Gatorade Flow. In 2017, this man's newly acquired teammate told him \they say I gotta come off the bench." This man missed nearly the entire 2014-2015 season after suffering a horrific leg injury while practicing for the US National Team. Sam Presti sent Domantas Sabonis and Victor Oladipo to the Indiana Pacers in exchange for this player, who then surprisingly didn't bolt to the Lakers in the 2018 off-season. For the point, name this player who formed an unsuccessful \Big Three" with Carmelo Anthony and Russell Westbrook on the Oklahoma City Thunder. ANSWER: Paul Clifton Anthony George (accept PG13) (Tossup 2) This series used Ratatat's \Cream on Chrome" as background music for many early episodes. Side projects of this series include a \Bedtime" version featuring literature readings and an educational \Basics" version. This series' 2019 April Fools' Day gag involved the a 4Kids dub of Pokemon claiming that Brock loved jelly donuts. This series celebrated million-subscriber benchmarks with episodes featuring the Taco Town 15-layer taco and the Every-Meat Burrito and Death Sandwich from Regular Show. For the point, name this YouTube channel starring Andrew Rea, who cooks various foods as inspired by popular culture. ANSWER: Binging with Babish (Tossup 3) The creators of this game recently announced a \Royal" edition which will add a third semester of gameplay. In April 2019, a heavily criticzed Kotaku article claimed that this game's theme song, \Wake up, Get up, Get out there," contains a slur against people with learning disabilities. -

Current Review

Current Review Richard Strauss & Dmitri Shostakovich: Sonatas for Violin & Piano aud 97.759 EAN: 4022143977595 4022143977595 Fanfare (Huntley Dent - 2019.08.01) I’m at a loss whether to call this unusual juxtaposition of Strauss and Shostakovich balanced or schizoid—all the melodic rapture belongs to Strauss, all the deep tragic feeling to Shostakovich. In the Victorian era a violin sonata couldn’t be all marzipan and sunshine without exhibiting post-Paganini virtuosity. Neither of these works complies. Strauss’s Violin Sonata dates from the years, 1887 and 1888, when he was ready to burst forth with great orchestral tone poems, and at times, as in the opening piano flourish that aspires to be the opening of Ein Heldenleben, you can hear that Strauss needed a grander stage than chamber music affords. He doesn’t particularly exploit the violin’s ability to dazzle except in passing moments, so his Violin Sonata must fly on the wings of song, which is does quite lusciously. Since I’ve never collected the work, I have no decided opinions about existing recordings, but to my ears the superb German violinist Franziska Pietsch and competition-winning Spanish pianist Josu De Solaun offer an ideal performance. I’ve admired every release I’ve heard from Pietsch, who has grown into a major interpretative talent from her beginnings as a child prodigy in East Germany. Her playing exhibits real command besides the expected tonal beauty, perfect technique, and musicality. Strauss wrote a solo-quality part for the piano, too, and De Solaun takes full advantage in bold, bravura style. -

The New Identity of Volkswagen That Fooled the World

The new identity of Volkswagen that fooled the world. It’s a surprise to many that Hitler, who is often referred to as the “personification of evil” (Rosenbaum, 1999), was integral to the design and launch of the Volkswagen Beetle, one of the most successful and iconic cars of our time. Hitler created various schemes for the German people to encourage them to buy into the Nazi regime. This is where the need for a ‘car for the people’ became apparent. Hitler charged Ferdinand Porsche with the task of designing a car that was not only affordable, but embodied Hitler’s desired lifestyle for the German people. The “slave labour at the Volkswagen car plant” (Press, 2014) that Porsche oversaw, reflected the institutionalised cruelty synonymous with concentration camps and Hitler’s reign in general. After the war, this undesirable link to the past meant that Volkswagen had to create a new image for itself quickly, if it was to succeed. A language was adopted, maybe not consciously, but it winds throughout all that Volkswagen do: semiotics. Semiotics, most simply explained, is the study of signs. Roland Barthes stated that “semiology aims to take in any system of signs, whatever their substance and limits; images, gestures, musical sounds, objects, and the complex associations of all of these, which form the content of ritual, convention or public entertainment: these constitute, if not languages, at least systems of signification.” (Barthes, 1972) Although it can be argued that semiotics is in everything, it has a particular relevance to Volkswagen, which employs the use of signs not merely as a coincidence, but as a well-orchestrated framework for the company. -

Hearing Wagner in "Till Eulenspiegel": Strauss's Merry

Hearing Wagner in Till Eulenspiegel: Strauss's Merry Pranks Reconsidered Matthew Bribitzer-Stull and Robert Gauldin Few would argue the influence Richard Wagner has exerted upon the history of Western art music. Among those who succeeded Wagner, this influence is perhaps most obvious in the works of Richard Strauss, the man Hans von Biilow and Alexander Ritter proclaimed Wagner's heir.1 While Strauss's serious operas and tone poems clearly derive from Wagner's compositional idiom, the lighter works enjoy a similar inheritance; Strauss's comic touch - in pieces from Till Eulenspiegel to Capriccio - adds an insouciant frivolity to a Wagnerian legacy often characterized as deeply emotional, ponderous, and even bombastic. light-hearted musics, however, are no less prone to posing interpretive dilemmas than are their serious counterparts. Till, for one, has remained notoriously problematic since its premiere. In addition to the perplexing Rondeauform marking on its title page, Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streicbe also remains enigmatic for historical and programmatic reasons. In addressing these problems, some scholars maintain that Strauss identified himself with his musical protagonist, thumbing his nose, as it were, at the musical philistines of the late romantic era. But the possibility that Till may bear an A version of this paper was presented at the Society for Music Theory annual meeting in Seattle, 2004. The authors wish to thank James Hepokoski and William Kinderman for their helpful suggestions. 'Hans von Biilow needs no introduction to readers of this journal, though Alexander Ritter may be less familiar. Ritter was a German violinist, conductor, and Wagnerian protege. It was Ritter, in part, who convinced Strauss to abandon his early, conservative style in favor of dramatic music - Ritter*s poem Tod und Verklarung appears as part of the published score of Strauss's work by the same name. -

A STUDY of STRAUSS by DANIEL GBEGOBY MASON Downloaded from I

A STUDY OF STRAUSS By DANIEL GBEGOBY MASON Downloaded from I. r • IU_K chronology of Bichard Strauss's artistic life up to the I present time arranges itself almost irresistibly in the traditional three periods, albeit in his case the philosophy of these periods has to be rather different from that, say, of http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ Beethoven's. "Discipline, maturity, eccentricity," we say with sufficient accuracy in describing Beethoven's development. The same formula for Strauss will perhaps be tempting to those for whom the perverse element in the Salome-Elektra period is the most striking one; but it is safer to say simply: "Music, program music, and music drama." Born in 1864, he produced during his student years, up to 1886, a great quantity of well-made at University of Birmingham on August 23, 2015 and to some extent personal music, obviously influenced by Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms, and comprising sonatas, quartets, concertos, and a symphony. He himself has told how he then came under the influence of Alexander Bitter, and through him of Wagner, Berlioz, and Liszt; how this influence toward "the poetic, the expressive, in music" acted upon him "like a storm wind"; and how the "Aus Italien," written in 1886, is the connecting link between his earlier work and the series of symphonic poems that follows in what I have called the second period. The chief titles and dates of this remarkable series may be itemized here: "Macbeth," 1886-7; "Don Juan," 1888; "Tod und Verklfirung," 1889; "Till Eulenspiegel" and "Also Sprach Zarathustra," 1894; "Don Quixote," 1897; "Ein Heldenleben," 1898; and the "Symphonia Domestica," 1903. -

Tthhheee Tttaaattttttooooo

TTHHEE TTAATTTTOOOO BRISTOL PRESS MAKING A PERMANENT IMPRESSION VOLUME 5 No. 13 ‘Futurama’ has lots ‘Gypsy’ setting up camp at BEHS of laugh potential By HILA YOSAFI and they wanted to use all the In “Gypsy,” Rose drives her directed and choreographed by musical talent Eastern had to two daughters into “Uncle Jerome Robbins. The Tatttoo offer. Jocko’s Kiddies Show,” and she By SUZANNE GREGORCZYK will be like in the future. We see how the writers imagine people A talented cast and crew at The musical takes place in the pushes one so much that she The Tattoo Bristol Eastern High School is 1920s and ’30s and is based on becomes a stripper! (Sorry, guys, After season after season of working hard to present “Gypsy” the life of Gypsy Rose Lee. she doesn’t really strip.) Going to the high ratings, the creators of this spring. The leads are Rose, the moth- Meanwhile, Herbie, who is “The Simpsons” have come up One of the stars of the musi- er, played by senior Jessica the manager of the dance with a new show. onon tthehe tubetube cal, senior Mike Santoro, said, Zarrella; Herbie, Rose’s troupe, tries to get Rose to show? “Futurama,” the new animat- “With anyone’s plays, Eastern or boyfriend, played by Santoro; marry him. “Gypsy” will be shown at ed comedy, which airs prime having jobs “assigned” to them Central, you can go even if June, Rose’s daughter, played by Of course, there is plenty of Eastern’s auditorium at 7 time on Tuesdays has, like “The instead of having a free will and you’re not excited about it in the junior April Street; and Louise, singing and dancing.