Final Dissertation Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/L CHOPIN's MAZURKA

17, ~A/l CHOPIN'S MAZURKA: A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF J. S. BACH--F. BUSONI, D. SCARLATTI, W. A. MOZART, L. V. BEETHOVEN, F. SCHUBERT, F. CHOPIN, M. RAVEL AND K. SZYMANOWSKI DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial. Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Jan Bogdan Drath Denton, Texas August, 1969 (Z Jan Bogdan Drath 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . I PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS First Recital . , , . ., * * 4 Second Recital. 8 Solo and Chamber Music Recital. 11 Lecture-Recital: "Chopin's Mazurka" . 14 List of Illustrations Text of the Lecture Bibliography TAPED RECORDINGS OF PERFORMANCES . Enclosed iii INTRODUCTION This dissertation consists of four programs: one lec- ture-recital, two recitals for piano solo, and one (the Schubert program) in combination with other instruments. The repertoire of the complete series of concerts was chosen with the intention of demonstrating the ability of the per- former to project music of various types and composed in different periods. The first program featured two complete sets of Concert Etudes, showing how a nineteenth-century composer (Chopin) and a twentieth-century composer (Szymanowski) solved the problem of assimilating typical pianistic patterns of their respective eras in short musical forms, These selections are preceded on the program by a group of compositions, consis- ting of a. a Chaconne for violin solo by J. S. Bach, an eighteenth-century composer, as. transcribed for piano by a twentieth-century composer, who recreated this piece, using all the possibilities of modern piano technique, b. -

CHAN 6659(4) CHAN 6659 BOOK.Qxd 22/5/07 4:12 Pm Page 2

CHAN 6659 Cover.qxd 22/5/07 4:08 pm Page 1 CHAN 6659(4) CHAN 6659 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 4:12 pm Page 2 Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) Sonata No. 2 in D major, Op. 94a 23:52 5 I Moderato 8:10 COMPACT DISC ONE 6 II Presto 4:40 Sonata No. 1 in G major, Op. 78 29:26 7 III Andante 3:50 1 I Vivace ma non troppo 11:14 8 IV Allegro con brio 7:02 2 II Adagio 8:51 TT 53:34 3 III Allegro molto moderato 9:16 COMPACT DISC THREE Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 100 20:24 Franz Schubert (1797–1828) 4 I Allegro amabile 8:23 5 II Andante tranquillo – Vivace 6:37 Sonata in A major for Violin and Piano, 6 III Allegretto grazioso (quasi andante) 5:21 Op. post. 162 D574 21:43 1 I Allegro moderato 8:21 Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 108 21:41 2 II Scherzo and Trio 4:04 7 I Allegro 8:29 3 III Andantino 4:13 8 II Adagio 4:33 4 IV Allegro vivace 4:58 9 III Un poco presto e con sentimento 2:46 10 IV Presto agitato 5:39 5 Fantasie in C major for Violin and Piano, TT 71:44 Op. post. 159 D934 25:41 COMPACT DISC TWO Sergey Sergeyevich Prokofiev (1891–1953) Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 80 29:31 Sonata in E flat major, Op. 18 32:02 1 I Andante assai 7:01 6 I Allegro ma non troppo 12:24 2 II Allegro brusco 7:01 7 II Improvisation. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

Current Review

Current Review Richard Strauss & Dmitri Shostakovich: Sonatas for Violin & Piano aud 97.759 EAN: 4022143977595 4022143977595 Fanfare (Huntley Dent - 2019.08.01) I’m at a loss whether to call this unusual juxtaposition of Strauss and Shostakovich balanced or schizoid—all the melodic rapture belongs to Strauss, all the deep tragic feeling to Shostakovich. In the Victorian era a violin sonata couldn’t be all marzipan and sunshine without exhibiting post-Paganini virtuosity. Neither of these works complies. Strauss’s Violin Sonata dates from the years, 1887 and 1888, when he was ready to burst forth with great orchestral tone poems, and at times, as in the opening piano flourish that aspires to be the opening of Ein Heldenleben, you can hear that Strauss needed a grander stage than chamber music affords. He doesn’t particularly exploit the violin’s ability to dazzle except in passing moments, so his Violin Sonata must fly on the wings of song, which is does quite lusciously. Since I’ve never collected the work, I have no decided opinions about existing recordings, but to my ears the superb German violinist Franziska Pietsch and competition-winning Spanish pianist Josu De Solaun offer an ideal performance. I’ve admired every release I’ve heard from Pietsch, who has grown into a major interpretative talent from her beginnings as a child prodigy in East Germany. Her playing exhibits real command besides the expected tonal beauty, perfect technique, and musicality. Strauss wrote a solo-quality part for the piano, too, and De Solaun takes full advantage in bold, bravura style. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Hearing Wagner in "Till Eulenspiegel": Strauss's Merry

Hearing Wagner in Till Eulenspiegel: Strauss's Merry Pranks Reconsidered Matthew Bribitzer-Stull and Robert Gauldin Few would argue the influence Richard Wagner has exerted upon the history of Western art music. Among those who succeeded Wagner, this influence is perhaps most obvious in the works of Richard Strauss, the man Hans von Biilow and Alexander Ritter proclaimed Wagner's heir.1 While Strauss's serious operas and tone poems clearly derive from Wagner's compositional idiom, the lighter works enjoy a similar inheritance; Strauss's comic touch - in pieces from Till Eulenspiegel to Capriccio - adds an insouciant frivolity to a Wagnerian legacy often characterized as deeply emotional, ponderous, and even bombastic. light-hearted musics, however, are no less prone to posing interpretive dilemmas than are their serious counterparts. Till, for one, has remained notoriously problematic since its premiere. In addition to the perplexing Rondeauform marking on its title page, Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streicbe also remains enigmatic for historical and programmatic reasons. In addressing these problems, some scholars maintain that Strauss identified himself with his musical protagonist, thumbing his nose, as it were, at the musical philistines of the late romantic era. But the possibility that Till may bear an A version of this paper was presented at the Society for Music Theory annual meeting in Seattle, 2004. The authors wish to thank James Hepokoski and William Kinderman for their helpful suggestions. 'Hans von Biilow needs no introduction to readers of this journal, though Alexander Ritter may be less familiar. Ritter was a German violinist, conductor, and Wagnerian protege. It was Ritter, in part, who convinced Strauss to abandon his early, conservative style in favor of dramatic music - Ritter*s poem Tod und Verklarung appears as part of the published score of Strauss's work by the same name. -

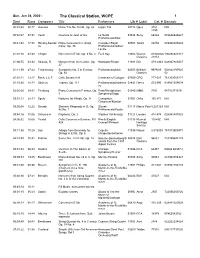

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Jun 28, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 30:17 Hummel Piano Trio No. 5 in E, Op. 83 Gajan Trio 02772 Opus 9351 N/A 2255 00:32:4707:31 Verdi Overture to Joan of Arc La Scala 03534 Sony 68468 074646846827 Philharmonic/Muti 00:41:48 17:58 Rimsky-Korsak Piano Concerto in C sharp Campbell/Royal 04500 Telarc 80454 089408045424 ov minor, Op. 30 Philharmonic/Gilbert Levine 01:01:1604:39 Chopin Nocturne in E flat, Op. 9 No. 2 Fazil Say 13305 Warner 01902958 190295821814 Classics 21814 01:06:5503:34 Strauss, R. Morgen! from Vier Lieder, Op. Hampson/Rieger 11991 DG 479 2943 028947929437 27 01:11:5947:42 Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Philharmonia/Muti 04055 Brilliant 99792/5 502842197925 Op. 64 Classics 02 02:01:1113:27 Bach, J.C.F. Cello Sonata in A Camerata of Cologne 07350 CPO 777 087 761203708727 02:15:38 18:12 Sibelius Tapiola, Op. 112 Philharmonia/Ashkena 02843 Decca 473 590 028947359029 zy 02:35:2024:21 Thalberg Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. Ponti/Westphalian 01040 MMG 7151 04716371519 5 Symphony/Kapp 03:01:11 28:13 Spohr Notturno for Winds, Op. 34 Consortium 01761 Orfeo 155 871 N/A Classicum/Klocker 03:30:5412:22 Dvorak Slavonic Rhapsody in D, Op. Slovak 01117 Marco Polo 8.223129 N/A 45 No. 1 Philharmonic/Kosler 03:44:16 15:06 Schumann Papillons, Op. 2 Vladimir Ashkenazy 01129 London 414 474 028941447425 04:00:5210:06 Vivaldi Cello Concerto in B minor, RV Pleeth/English 01136 Musical 11085Z N/A 424 Concert/Pinnock Heritage Society 04:11:5810:25 Suk Adagio from Serenade for Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Strings in E flat, Op. -

A STUDY of STRAUSS by DANIEL GBEGOBY MASON Downloaded from I

A STUDY OF STRAUSS By DANIEL GBEGOBY MASON Downloaded from I. r • IU_K chronology of Bichard Strauss's artistic life up to the I present time arranges itself almost irresistibly in the traditional three periods, albeit in his case the philosophy of these periods has to be rather different from that, say, of http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ Beethoven's. "Discipline, maturity, eccentricity," we say with sufficient accuracy in describing Beethoven's development. The same formula for Strauss will perhaps be tempting to those for whom the perverse element in the Salome-Elektra period is the most striking one; but it is safer to say simply: "Music, program music, and music drama." Born in 1864, he produced during his student years, up to 1886, a great quantity of well-made at University of Birmingham on August 23, 2015 and to some extent personal music, obviously influenced by Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms, and comprising sonatas, quartets, concertos, and a symphony. He himself has told how he then came under the influence of Alexander Bitter, and through him of Wagner, Berlioz, and Liszt; how this influence toward "the poetic, the expressive, in music" acted upon him "like a storm wind"; and how the "Aus Italien," written in 1886, is the connecting link between his earlier work and the series of symphonic poems that follows in what I have called the second period. The chief titles and dates of this remarkable series may be itemized here: "Macbeth," 1886-7; "Don Juan," 1888; "Tod und Verklfirung," 1889; "Till Eulenspiegel" and "Also Sprach Zarathustra," 1894; "Don Quixote," 1897; "Ein Heldenleben," 1898; and the "Symphonia Domestica," 1903. -

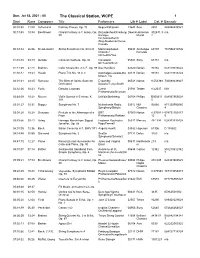

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Jul 18, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:00 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 Segev/Pohjonen 13643 Avie 2389 822252238921 00:13:4518:34 Beethoven Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. Bezuidenhout/Freiburg DownloadHarmonia 902431.3 n/a 80 Baroque Mundi 2 Orchestra/Zurich Zing-Akademie/Heras- Casado 00:33:34 26:06 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 08 in D Metamorphosen 05480 Archetype 60107 701556010726 Chamber Records Orchestra/Yoo 01:01:1009:19 Dvorak Carnival Overture, Op. 92 Cleveland 05021 Sony 63151 n/a Orchestra/Szell 01:11:2927:48 Brahms Cello Sonata No. 2 in F, Op. 99 Diaz/Sanders 02520 Dorian 90165 053479016522 01:40:47 19:24 Haydn Piano Trio No. 43 in C Kalichstein-Laredo-Ro 02473 Dorian 90164 053479016423 binson Trio 02:01:4129:45 Rameau The Birth of Osiris (Suite for Ensemble 06541 Naxos 8.553388 730099438827 Orchestra) Savaria/Terey-Smith 02:32:26 10:43 Fucik Danube Legends Czech 01781 Teldec 8.42337 N/A Philharmonic/Neuman 02:44:0915:48 Mozart Violin Sonata in E minor, K. Uchida/Steinberg 04768 Philips B000411 028947565628 304 5 03:01:27 35:31 Dopper Symphony No. 7 Netherlands Radio 03512 NM 92060 871330992060 Symphony/Bakels Classics 4 03:38:2810:28 Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a BRT 07909 Naxos 8.570011- 074731300117 Faun Philharmonic/Rahbari 12 0 03:49:56 09:43 Grieg Homage March from Sigurd Eastman Rochester 05011 Mercury 434 394 028943439428 Jorsalfar, Op. 56 Pops/Fennell 04:01:0912:36 Bach Italian Concerto in F, BWV 971 Angela Hewitt 03592 Hyperion 67306 D 138602 04:14:4530:55 Diamond Symphony No. -

Chopin Research Paper 2

Leigh Urbschat 5/16/07 Piano in the Age of Chopin Research Paper Viardot’s Adapted Mazurkas: The Link Between Chopin’s Two Styles As a Polish native during the time of revolution, it is no wonder that Chopin’s music expresses nationalistic qualities. His well known mazurkas, polonaises, and ballades are all influenced by traditional Polish folk music. The songs of Chopin, however, are a relatively unknown genre in the composer’s repertoire. It is these songs, especially those that are mazurkas, which exemplify Chopin’s nationalistic feelings to their full extent. In considering Op. 74, however, we find that these songs are not what one would expect of Chopin within this genre. Chopin’s piano music, influenced by 19th century Italian opera, is known for its lyrical quality, chromaticism and complex harmonies. These qualities, which can be heard especially in the piano mazurkas, are significantly diminished in the mazurka songs. In listening to the piano mazurkas and vocal mazurkas one after the other, it seems that if the piano mazurkas were given texts they would become the vocal mazurkas a listener familiar with Chopin’s piano music would expect to hear. This is exactly what Pauline Viardot did with her collection of twelve adapted mazurkas. By fitting texts to Chopin’s piano mazurkas she was able to give listeners the vocal mazurkas that they expected from Chopin. Chopin’s vocal mazurkas, however, stray from the composer’s familiar style in order to stray true to their Polish origins. Chopin follows the guidelines of Józef Elsner’s treatise on vernacular pronunciation and syllabic placement in order to stay true to his Polish roots.1 With the mazurka songs, the importance of metrical structure in the vernacular settings overrides that of harmonic and melodic creativity. -

View Repertoire List

Repertoire List Victor Lim Solo J.S. Bach Prelude and Fugue in F sharp major Book 1 BWV 858 Prelude and Fugue in B flat major Book 1 BWV 866 Prelude and Fugue in F major Book 2 BWV 880 Bach/F,Busoni Chorale Prelude ‘Wachet Auf, Ruft Uns Die Stimme’ Bach/Cohen Chorale Prelude ‘Ertödt' uns durch dein' Güte’ Bach/Siloti Prelude in B minor J. Rameau La Dauphine D. Scarlatti Sonata in C K159 L.v. Beethoven Piano Sonata No.10 Op.14 No.2 Piano Sonata No.21 Op.53 'Waldstein' Piano Sonata No.26 Op.81a 'Les Adieux' Piano Sonata No.25 Op.57 ‘Appassionata’ Piano Sonata No.29 Op.106 ‘Hammerklavier’ J. Haydn Piano Sonata in F major Hob.XVI.23 Piano Sonata in B minor Hob.XVI:32 Piano Sonata in E minor Hob.XVI:34 Piano Sonata in C major Hob.XVI:50 W.A. Mozart Piano Sonata in B flat major K.570 Piano Sonata in A minor K.310 F. Schubert Piano Sonata No.13 in A major D.664 Allegreto in C minor D.915 J. Brahms 6 Klavierstücke Op.118 F. Bridge Three sketches F. Chopin Etudes Op.10 No.1,2,3,5,10,12 Fantaisie Op.49 Ballade No.4 Op.52 Barcarolle Op.60 Preludes Op.28 Mazurkas Op.59 Nocturne Op.9 No.2, Op.32 No.1&2 P. Grainger Ramble on the last duet in Richard Strauss’s Opera ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ E. Grieg Lyric Pieces Op.12 No.1, ‘Arietta’, Op.47 No.3 ‘Melodie’, Op.54 No.4 ‘Nocturne F.