A STUDY of STRAUSS by DANIEL GBEGOBY MASON Downloaded from I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Dissertation Document

Abstract Title of Dissertation: INFLUENCES AND TRANSFORMATIONS: 19TH- CENTURY SOLO AND COLLABORATIVE PIANO REPERTOIRE Miori Sugiyama, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2012 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music, Piano Division This dissertation is an exploration of the inter-relationships of genres in the collaborative piano repertoire, particularly in music of the 19th century, an especially important period for collaborative piano repertoire. During this time, much of the repertoire gave equal importance to the piano in duo and ensemble repertoire. Starting with Schubert, and becoming more apparent with the development of the German lied, the piano became a more integral part of any composition, the piano part being no longer simplistic but rather a collaborative partner with its own voice. Mendelssohn transformed the genre of lieder by writing them, without their words, for solo piano. In addition to creating some of the greatest and most representative lieder in the Romantic period, composers such as Schumann, Brahms, and Strauss continued the evolution of the sonata by writing works that were more technically demanding on the performer, musically innovative, and structurally still evolving. In the case of Chopin who wrote mostly piano works, a major influence came from the world of opera, particularly the Bel Canto style. In exploring two specific genres, vocal and instrumental piano works by these composers; it is fascinating to see how one genre translates to another genre. This was especially true in the vocal and instrumental works by Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Chopin, and Strauss. All of these composers, with the exception of Chopin, contributed equally to both the song and sonata genres. -

CHAN 6659(4) CHAN 6659 BOOK.Qxd 22/5/07 4:12 Pm Page 2

CHAN 6659 Cover.qxd 22/5/07 4:08 pm Page 1 CHAN 6659(4) CHAN 6659 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 4:12 pm Page 2 Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) Sonata No. 2 in D major, Op. 94a 23:52 5 I Moderato 8:10 COMPACT DISC ONE 6 II Presto 4:40 Sonata No. 1 in G major, Op. 78 29:26 7 III Andante 3:50 1 I Vivace ma non troppo 11:14 8 IV Allegro con brio 7:02 2 II Adagio 8:51 TT 53:34 3 III Allegro molto moderato 9:16 COMPACT DISC THREE Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 100 20:24 Franz Schubert (1797–1828) 4 I Allegro amabile 8:23 5 II Andante tranquillo – Vivace 6:37 Sonata in A major for Violin and Piano, 6 III Allegretto grazioso (quasi andante) 5:21 Op. post. 162 D574 21:43 1 I Allegro moderato 8:21 Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 108 21:41 2 II Scherzo and Trio 4:04 7 I Allegro 8:29 3 III Andantino 4:13 8 II Adagio 4:33 4 IV Allegro vivace 4:58 9 III Un poco presto e con sentimento 2:46 10 IV Presto agitato 5:39 5 Fantasie in C major for Violin and Piano, TT 71:44 Op. post. 159 D934 25:41 COMPACT DISC TWO Sergey Sergeyevich Prokofiev (1891–1953) Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 80 29:31 Sonata in E flat major, Op. 18 32:02 1 I Andante assai 7:01 6 I Allegro ma non troppo 12:24 2 II Allegro brusco 7:01 7 II Improvisation. -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

Current Review

Current Review Richard Strauss & Dmitri Shostakovich: Sonatas for Violin & Piano aud 97.759 EAN: 4022143977595 4022143977595 Fanfare (Huntley Dent - 2019.08.01) I’m at a loss whether to call this unusual juxtaposition of Strauss and Shostakovich balanced or schizoid—all the melodic rapture belongs to Strauss, all the deep tragic feeling to Shostakovich. In the Victorian era a violin sonata couldn’t be all marzipan and sunshine without exhibiting post-Paganini virtuosity. Neither of these works complies. Strauss’s Violin Sonata dates from the years, 1887 and 1888, when he was ready to burst forth with great orchestral tone poems, and at times, as in the opening piano flourish that aspires to be the opening of Ein Heldenleben, you can hear that Strauss needed a grander stage than chamber music affords. He doesn’t particularly exploit the violin’s ability to dazzle except in passing moments, so his Violin Sonata must fly on the wings of song, which is does quite lusciously. Since I’ve never collected the work, I have no decided opinions about existing recordings, but to my ears the superb German violinist Franziska Pietsch and competition-winning Spanish pianist Josu De Solaun offer an ideal performance. I’ve admired every release I’ve heard from Pietsch, who has grown into a major interpretative talent from her beginnings as a child prodigy in East Germany. Her playing exhibits real command besides the expected tonal beauty, perfect technique, and musicality. Strauss wrote a solo-quality part for the piano, too, and De Solaun takes full advantage in bold, bravura style. -

Hearing Wagner in "Till Eulenspiegel": Strauss's Merry

Hearing Wagner in Till Eulenspiegel: Strauss's Merry Pranks Reconsidered Matthew Bribitzer-Stull and Robert Gauldin Few would argue the influence Richard Wagner has exerted upon the history of Western art music. Among those who succeeded Wagner, this influence is perhaps most obvious in the works of Richard Strauss, the man Hans von Biilow and Alexander Ritter proclaimed Wagner's heir.1 While Strauss's serious operas and tone poems clearly derive from Wagner's compositional idiom, the lighter works enjoy a similar inheritance; Strauss's comic touch - in pieces from Till Eulenspiegel to Capriccio - adds an insouciant frivolity to a Wagnerian legacy often characterized as deeply emotional, ponderous, and even bombastic. light-hearted musics, however, are no less prone to posing interpretive dilemmas than are their serious counterparts. Till, for one, has remained notoriously problematic since its premiere. In addition to the perplexing Rondeauform marking on its title page, Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streicbe also remains enigmatic for historical and programmatic reasons. In addressing these problems, some scholars maintain that Strauss identified himself with his musical protagonist, thumbing his nose, as it were, at the musical philistines of the late romantic era. But the possibility that Till may bear an A version of this paper was presented at the Society for Music Theory annual meeting in Seattle, 2004. The authors wish to thank James Hepokoski and William Kinderman for their helpful suggestions. 'Hans von Biilow needs no introduction to readers of this journal, though Alexander Ritter may be less familiar. Ritter was a German violinist, conductor, and Wagnerian protege. It was Ritter, in part, who convinced Strauss to abandon his early, conservative style in favor of dramatic music - Ritter*s poem Tod und Verklarung appears as part of the published score of Strauss's work by the same name. -

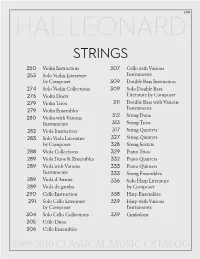

Strings: 6/18/09 4:05 PM Page 249 HAL LEONARD249 STRINGS

76164 7 Classical_Strings: 6/18/09 4:05 PM Page 249 HAL LEONARD249 STRINGS 250 Violin Instruction 307 Cello with Various 253 Solo Violin Literature Instruments by Composer 309 Double Bass Instruction 274 Solo Violin Collections 309 Solo Double Bass 276 Violin Duets Literature by Composer 279 Violin Trios 311 Double Bass with Various 279 Instruments Violin Ensembles 312 280 Violin with Various String Duos Instruments 313 String Trios 282 Viola Instruction 317 String Quartets 283 Solo Viola Literature 327 String Quintets by Composer 328 String Sextets 288 Viola Collections 329 Piano Trios 289 Viola Duos & Ensembles 332 Piano Quartets 289 Viola with Various 333 Piano Quintets Instruments 333 String Ensembles 289 Viola d’Amore 336 Solo Harp Literature 289 Viola da gamba by Composer 290 Cello Instruction 338 Harp Ensembles 291 Solo Cello Literature 339 Harp with Various by Composer Instruments 304 Solo Cello Collections 339 Cimbalom 305 Cello Duos 306 Cello Ensembles 2009-2010 CLASSICAL MUSIC CATALOG 76164 7 Classical_Strings: 6/18/09 4:05 PM Page 250 250 VIOLIN INSTRUCTION BERIOT, CHARLES DE ______50326680 Practical Method, Book 3 ______50326200 Method for Violin, Part 1 Unaccompanied Spanish/English. Schirmer ED1277 .............................$9.95 Schirmer ED1005 ..........................................................$9.95 ______50326690 Practical Method, Book 4 ______50091100 Violin Method Part 1 Ricordi RER802 .....................$24.95 Spanish/English. Schirmer ED1278 .............................$9.95 ______50326700 Practical Method, -

Cornerstones of the Ukrainian Violin Repertoire 1870 – Present Day

Cornerstones of the Ukrainian violin repertoire 1870 – present day Carissa Klopoushak Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, Quebec January 2013 A doctoral paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Music in Performance Studies © Carissa Klopoushak 2013 i Abstract: The unique violin repertoire by Ukrainian composers is largely unknown to the rest of the world. Despite cultural and political oppression, Ukraine experienced periods of artistic flurry, notably in the 1920s and the post-Khrushchev “Thaw” of the 1960s. During these exciting and experimental times, a greater number of substantial works for violin began to appear. The purpose of the paper is one of recovery, showcasing the cornerstone works of the Ukrainian violin repertoire. An exhaustive history of this repertoire does not yet exist in any language; this is the first resource in English on the topic. This paper aims to fill a void in current scholarship by recovering this substantial but neglected body of works for the violin, through detailed discussion and analysis of selected foundational works of the Ukrainian violin repertoire. Focusing on Maxym Berezovs´kyj, Mykola Lysenko, Borys Lyatoshyns´kyj, Valentyn Sil´vestrov, and Myroslav Skoryk, I will discuss each composer's life, oeuvre at large, and influences, followed by an in-depth discussion of his specific cornerstone work or works. I will also include cultural, musicological, and political context when applicable. Each chapter will conclude with a discussion of the reception history of the work or works in question and the influence of the composer on the development of violin writing in Ukraine. -

Music Manuscripts and Books Checklist

THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM MASTERWORKS FROM THE MORGAN: MUSIC MANUSCRIPTS AND BOOKS The Morgan Library & Museum’s collection of autograph music manuscripts is unequaled in diversity and quality in this country. The Morgan’s most recent collection, it is founded on two major gifts: the collection of Mary Flagler Cary in 1968 and that of Dannie and Hettie Heineman in 1977. The manuscripts are strongest in music of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. Also, the Morgan has recently agreed to purchase the James Fuld collection, by all accounts the finest private collection of printed music in the world. The collection comprises thousands of first editions of works— American and European, classical, popular, and folk—from the eighteenth century to the present. The composers represented in this exhibition range from Johann Sebastian Bach to John Cage. The manuscripts were chosen to show the diversity and depth of the Morgan’s music collection, with a special emphasis on several genres: opera, orchestral music and concerti, chamber music, keyboard music, and songs and choral music. Recordings of selected works can be heard at music listening stations. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Der Schauspieldirektor, K. 486. Autograph manuscript of the full score (1786). Cary 331. The Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection. Mozart composed this delightful one-act Singspiel—a German opera with spoken dialogue—for a royal evening of entertainment presented by Emperor Joseph II at Schönbrunn, the royal summer residence just outside Vienna. It took the composer a little over two weeks to complete Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario). The slender plot concerns an impresario’s frustrated attempts to assemble the cast for an opera. -

Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient

29 9. (783) Summarize the paragraph "Songs in the symphonies." Chapter 32 Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer, 1883- The Early Twentieth Century: 85, rev. 1891-96) are in the first and last movements of The Classical Tradition the first symphony (1884-88, rev. 1893-96, 1906) Voices in four symphonies (2d, 1888-94, rev. 1906; and 8th, 1. [778] What was the conundrum for modernist composers 1906-7, the most) in the classical tradition? What two things did they have Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy's Magic Horn, 1892-98) to do? are found in symphonies no. 2, no. 3 (1893-96, rev. Writing music that would compete with the repertoire. 1906), and no. 4 (1892-1900, rev. 1901-10) Write music that offered something new and that the listeners would accept. High quality, lasting value through many 10. "Mahler extended Beethoven's concept of the symphony rehearings and close study; a distinct style as a bold personal statement." The pieces are long. The instrumentation is also quite large and there is great 2. (779) TQ: What does post-tonal mean? See p. 808 for variety in the orchestration. Mahler "envisioned music as avant-garde. an art not just of notes but of sound itself, an approach Music that is too far away from common practice (= 18th- that became more common over the course of the 20th century theory = freshman/sophomore music theory) century." 11. (784) Stories for Mahler's first four symphonies were 3. Understand the difference between the 18th-century and written but they were ______. -

San Francisco Symphony 2017-2018 Season Concert Calendar

Contact: Public Relations San Francisco Symphony (415) 503-5474 [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / MARCH 6, 2017 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY 2017-2018 SEASON CONCERT CALENDAR PLEASE NOTE: Subscription packages for the San Francisco Symphony’s 2017-18 season go on sale TUESDAY, March 7 at 10 am at www.sfsymphony.org/1718season, (415) 864-6000, and at the Davies Symphony Hall Box Office, located on Grove Street between Franklin and Van Ness. Additional information about subscription packages and season highlights is available prior to the on-sale date at www.sfsymphony.org/1718season. All concerts are at Davies Symphony Hall, 201 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, unless otherwise noted OPENING NIGHT GALA with YO-YO MA Thursday, September 14, 2017 at 8 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Yo-Yo Ma cello San Francisco Symphony BERNSTEIN Overture to Candide SAINT-SAËNS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Opus 33 TCHAIKOVSKY Variations on a Rococo Theme RAVEL Boléro SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY AND CHORUS, MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS CONDUCTING Friday, September 22, 2017 at 8 pm Saturday, September 23, 2017 at 8 pm Sunday, September 24, 2017 at 2 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Isabel Leonard mezzo-soprano Ryan McKinny bass-baritone [SFS debut] Carey Bell clarinet San Francisco Symphony Chorus, Ragnar Bohlin director San Francisco Symphony BERNSTEIN Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs BERNSTEIN Chichester Psalms BERNSTEIN (arr. Coughlin) Arias and Barcarolles BERNSTEIN (orch. Kostal, Ramin) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story San Francisco Symphony 2017-18 Season Calendar – Page 2 of 18 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS CONDUCTING Thursday, September 28, 2017 at 8 pm Saturday, September 30, 2017 at 8 pm Sunday, October 1, 2017 at 2 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Jeremy Denk piano San Francisco Symphony BARTÓK Piano Concerto No. -

47Th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES Week 2 July 21–27, 2019

th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES 47 Week 2 July 21–27, 2019 Sunday, July 21, 6 p.m. The marking for the first movement is of study at the University of California, San Monday, July 22, 6 p.m. unusual: Allegramente is an indication Diego, in the mid-1980s that brought a new more of character than of speed. (It means and important addition to his compositional ZOLTÁN KODÁLY (1882–1967) “brightly, gaily.”) The movement opens palette: computers. Serenade for Two Violins & Viola, Op. 12 immediately with the first theme—a sizzling While studying with Roger Reynolds, Vinko (1919–20) duet for the violins—followed by a second Globokar, and Joji Yuasa, Wallin became subject in the viola that appears to be the interested in mathematical and scientific This Serenade is for the extremely unusual song of the suitor. These two ideas are perspectives. He also gained further exposure combination of two violins and a viola, and then treated in fairly strict sonata form. to the works of Xenakis, Stockhausen, and Kodály may well have had in mind Dvorˇ ák’s The second movement offers a series of Berio. The first product of this new creative Terzetto, Op. 74—the one established work dialogues between the lovers. The viola mix was his Timpani Concerto, composed for these forces. Kodály appears to have been opens with the plaintive song of the man, between 1986 and 1988. attracted to this combination: in addition and this theme is reminiscent of Bartók’s Wallin wrote Stonewave in 1990, on to the Serenade, he wrote a trio in E-flat parlando style, which mimics the patterns commission from the Flanders Festival, major for two violins and viola when he was of spoken language. -

Season 2014-2015

27 Season 2014-2015 Friday, September 26, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, September 27, at 8:00 Sunday, September 28, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 2:00 Lang Lang Piano Saint-Saëns “Bacchanale,” from Samson and Delilah (9/26 only) Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia (9/27 only) Williams Essay for Strings (9/28 only) Mozart Piano Concerto No. 17 in G major, K. 453 I. Allegro II. Andante III. Allegretto—Presto Intermission Strauss An Alpine Symphony, Op. 64 This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. The opening works on these concerts were voted on and chosen by the audience. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 28 Please join us immediately following the September 28 concert for a Chamber Postlude, featuring members of The Philadelphia Orchestra. Strauss Violin Sonata in E-flat major, Op. 18 I. Allegro ma non troppo II. Improvisation: Andante cantabile III. Finale: Andante—Allegro Dara Morales Violin Amy Yang Piano 3 Story Title 29 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. The Orchestra is transforming its rich tradition of achievement, sustaining the highest level of artistic quality, but also challenging—and exceeding—that level by creating powerful musical experiences for audiences at home and around the world.