4 Views from England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niigata, Sado Island & Tokyo Fall Foliage Tour

Niigata, Sado Island & Tokyo Fall Foliage Tour October 31st - November 9th, 2021 In Hot Water-Onsen & Sake Dream Tour 9nts/11days from: $3,695 triple; $3,795 double; $4,295 single Cancel for any reason up to 60 days prior-FULL REFUND! Maximum Tour size is 24 tour members! Little visited and often overlooked, Niigata is a beautiful remote region with fabulous sights, great food, and excellent countryside landscapes -deserving much more attention than it gets. 200 miles northwest from Tokyo, the Niigata-Sado Island region offers a very different experience to the hustle and bustle of the Tokaido seaboard. It is koyo season and time to enjoy the grandeur of nature, the viewing of autumn colors, part of the Japanese culture dating back centuries. The trees clad themselves in brilliant scarlets and golds, offering a grand finale to the year as these beautiful landscapes spread around the Niigata prefecture. Besides some of the best sightseeing spot the tour also includes a ferry ride to Sado Island, bullet train to Tokyo, onsen stay, hands-on experiences, Japanese drum session, and saki tastings! We are also visiting Takasaki, home to towering Byakue Kannon statue, and Shorinzan Darumaji Temple, famous for its round daruma dolls, believed to bring good luck. And then, Minakami, a mountainous hot spring resort town. Not so quick, as we end in Tokyo, 2-nights, for that big city feel. Here we will be visiting the more popular spots, Tsukiji and Ameyoko. and Shibuya Sky for omiyage shopping along with Meiji Jingu Gaien to enjoy fall colors. Itinerary Day 1 – October 31st Sunday – Depart from Honolulu Hawaiian Airlines #863 Departs Honolulu at 1:35pm - Arrives Haneda at 5:1- pm + 1 Please meet your Panda Travel representative at the Hawaiian Airlines international check-in counters located in Terminal 2, Lobby 4 a minimum of 3 hours prior to the flight departure time Day 2 – November 1st - Wednesday –Haneda On arrival in Tokyo, please make your way to the baggage claim area and then proceed to customs clearing. -

Western Area Guidebook 406 151 a B C D E 62 16 Niigata Shibukawa 335

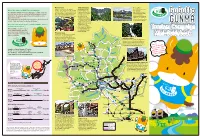

Gunma Gunma Prefecture Western Area Guidebook 406 151 A B C D E 62 16 Niigata Shibukawa 335 Mt. Harunasan J 334 o Shibukawa- 336 e Ikaho IC 338 Lake Harunako t s u Nagano S 1 h Yagihara 1 i Tochigi Haruna-jinja Shrine n 333 Gunma k 102 Dosojin a Annaka City Takasaki City n of Kurabuchi s e 333 Tomioka City n 114 406 Shimonita Town Kurabuchi Ogurinosato Kanra Town Roadside Station 338 Komayose PA 342 Ibaraki Misato Komayose Smart IC 17 333 Nanmoku Village Fujioka City Shibazakura Park Gumma-Soja 17 Ueno Village Kanna Town ay 3 Takasaki w il a Saitama City R n inkanse 102 u Sh Jomo Electri c 114 Western Gunma okurik H Chuo Maebashi Tokyo Chiba Maebashi IC 76 Yamanashi Maebashi 50 50 Shim- Lake Kirizumiko Hachimanzuka 2 Maebashi 2 Sunflower Maze R 波志江 293 yo m Kanagawa Annaka City o スマート IC 17 Aputo no Michi Li Annakaharuna 406 ne 17 Ino 波志江 PA 18 Akima Plum Grove Komagata IC 太田藪塚 IC 316 Lake Usuiko Touge no Yu Robai no Sato Haruna Fruit Road Takasakitonyamachi Maebashi- 伊勢崎 IC Yokokawa SA Gumma-Yawata Kita-Takasaki Karuizawa Usuitouge Tetsudo Minami IC Usui Silk 332 Bunka Mura Reeling Annaka Takasaki IC 太田桐生 IC What is Yokokawa 18 伊勢崎 Cooperative e i n Takasaki Pageant Takasaki Matsuida- L 354 Takasaki Annaka City Office Takasaki Myogi IC u of Starlight 78 Nishi-Matsuida s JCT 39 t City office e - Minami 354 Isobe Onsen i n Hanadaka Takasaki 2 Matsuida h Byakue Myogi-jinja S 18 Flower Hill Dai-kannon Takasaki-Tamamura 128 Shrine Isobeyana Lookout Kuragano Western Gunma like? Mt. -

The Usui Toge Railway of the Shin-Etsu Line, 1893–1997 Roderick A

Features Impact of Railways on Japanese Society & Culture The Usui Toge Railway of the Shin-etsu Line, 1893–1997 Roderick A. Smith most train trips have been significantly on the low-cost mass production end of Introduction speeded up. I wonder if our colleagues the market, with British Airways as one of in Japan will now turn to the integration its major customers. His company pro- One Sunday in late May 1995, I found of transport systems and the improvement duces about 25 million stainless steel myself in Tokyo with a rest day and a spare of door-to-door times? items a month at about US10¢ a piece of day on a weekly all-lines Japan Rail Pass. On a bill board near Tokyo Eki, a British which 40% goes to both the EC and the With a minimum of planning, I set out on diesel InterCity125, with its distinctive USA. No manufacturing is now done in a triangular journey (Fig. 1) linking Tokyo, wedge shaped front, was being used to Japan, the current production units are in Nagoya, Nagano and Tokyo. I had no advertise Castor Mild cigarettes; perhaps the Philippines and China, with Viet Nam particular purpose, other than to relax in it is fortunate that the associated logo was being eyed as the next base. However, the Green (First Class) Cars of Japan’s not, ‘Smoking Clean’! I departed on the all is not lost and I was gratified to see an excellent railway system, and to watch the Hikari 105 shinkansen exactly on sched- advertisement for Range Rovers in the on- scenery go by on a day of the week when ule at 08:31—all the trains I used departed board copy of L&G, JR Central’s in-house the rail service in the UK varies from ter- and arrived exactly on time. -

Kären WIGEN, a Malleable Map: Geographies of Restoration in Central Japan, 1600-1912. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010

Book Reviews / JESHO 54 (2011) 417-446 439 Kären WIGEN, A Malleable Map: Geographies of Restoration in Central Japan, 1600-1912. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010. xviii + 322 pp. ISBN: 978-0-520-25918-8 (hbk.). $39.95 / £27.95. Kären Wigen’s A Malleable Map opens with a big question: ‘How did modern Japan acquire its regional architecture?’ The obvious answer would be to look at Tokyo in 1871, ‘for it was there and then [. .] that the mod- ern political map was essentially put in place’ (1). This approach, however, does not satisfy Wigen, who chooses to tackle the issue from a regional standpoint by examining the trajectory of early modern Shinano province— modern Nagano prefecture—over the span of more than three centuries (1600-1912). In particular, Wigen wants to map out the ways in which Nagano’s regional identity came to be, and at which historical junctions. Here is the novelty: this is a book that outlines the Tokugawa-Meiji transi- tion not from the viewpoint of the domain but from that of the province (kuni), because ‘provincial identities counted’ (19) as well. At the same time A Malleable Map tells much more than just the story of the transfor- mation of a province into a prefecture. One of the first anecdotes inA Malleable Map presents the readers with the 1890 story of an unconscious politician forcibly carried out of his hos- pital bed and brought before the local assembly hall to achieve a spurious quorum for a vote on the location of the prefectural headquarters (5). -

Travel JAPAN

TRAVEL JAPAN The heritage village of Tsumago was the 42nd (of 69) post towns on the Nakasendo Way. OPPOSITE Momosuke- bashi is a 247-metre footbridge over the Kiso River in Nagiso. 96 JULY 2019 WALKING JAPAN Come September, Japan will reverberate to the roar of crowds and the shrill of referees’ whistles. In the run-up to the Rugby World Cup, we visited the island nation to hike its back roads. Once an ancient highway through the Japanese Alps from Kyoto to Tokyo, the Nakasendo Way is today a forgotten byway made for slackpacking holidays WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHS BY JUSTIN FOX getaway.co.za 97 TRAVEL JAPAN 98 JULY 2019 had always wanted to visit Japan in cherry-blossom season. The chance eventually came when I was put in touch with Walk Japan, a company that offers tours ranging from easy city walks to tough alpine treks. I chose their Nakasendo Way, a route that follows a Ifeudal highway through Honshu Island. After 27 hours of flying and transit via Joburg and Hong Kong, I arrived in Kyoto, Japan’s ancient capital, shattered and jetlagged, but still determined to see the city’s essential sights. Fortunately, there was a day to spare before the hike. Armed with a map, rudimentary instructions and TOP Young women of Kyoto come to pray at the Shinto shrine of Fushimi Inari Taisha. Google Translate, I climbed on a bus and ABOVE Traditional umbrellas at the golden-pavilion temple of Kinkaju-ji, Kyoto. set off. OPPOSITE This beautiful bamboo forest lies on a hill behind Tenryū-ji Temple, Kyoto. -

New Design T Template

one Shinano in the Nation the corpus of national maps (identified in Japanese as Nihon sOzu or Nihon zenzu) published before the Meiji era is large and varied. Within that corpus, it is possible to discern three fundamentally diªerent paradigms: a view from the west, a view from the east, and a view from the road. The oldest cartographic model was centered on Yamashiro Province, the region of the imperial capital.1 To a court residing near the shores of the Inland Sea, Shinsh[ was a strategic gateway to the eastern marches, a military fron- tier that was not fully subdued until the eleventh century.2 This chapter begins by recounting the court’s relationship with the province during its heyday. That relationship would fray badly during the succeeding centuries, which ended in a decisive shift of power to the east. Yet the Kyoto-centric paradigm proved resilient, resurging in various cartographic forms through- out the Tokugawa period. As a result, a geography of Shinano that had de- veloped in classical times remained in public view well into the nineteenth century. Long before that, however, a second conception of Japanese national space began to be articulated, one in which all roads led not to Kyoto but to Edo, the shogun’s headquarters at the edge of the KantO Plain. On maps com- piled by the Tokugawa shogunate, the military capital in the east over- shadowed the imperial complex in the west, emerging as the chief node of an expanded and reconfigured national network. This had important im- 3 1 plications for how Shinano was mapped. -

Shirakabado Workshop Where It Takes Only 20

Restaurant Kumoba Pond LOGTEI Shin-Karuizawa/ Naka-Karuizawa/ Sengataki Kyu-Karuizawa Foreign visitors have given this lake Enjoy a flavorful experience the name “Swan Lake.” In autumn, Sengataki Area Sengataki Waterfall is the From the middle of Meiji Period, a Canadian visitors can enjoy spectacular views largest waterfall in in a genuine log house. Karuizawa Area Guide of the red and gold leaves of the Naka-Karuizawa offers many spots to enjoy the Karuizawa, with a drop of missionary named A.C. Shaw and his family spent trees around the lake. A walk gifts of nature, such as the Wild Bird Wood, the approximately 20 meters. 1 their summers in Karuizawa. The rich green around the lake is an enjoyable 2 A 25 minute stroll on the crystal-clear Sengataki Waterfall, and the landscape of Karuizawa is dotted with cottages, experience in any season. walking path will provide murmuring Yukawa River. After enjoying a visitors with views of the Karuizawa can be roughly divided into five areas. the streets are lined with unique shops, and today MAP I-7 combination of nature walks and visits to art beautiful valley and the Each area has a wide selection of fascinating activities for the many people enjoy their vacation in the refreshing museums and literary monuments, we recommend waterfall. There is also a highlands of Karuizawa. paddling pool available. visitors - nature walks, shopping, eating at gourmet Shiraito Falls relaxing in one of the area’s hot springs. MAP E-4 restaurants, and visiting various places to appreciate art. A waterfall where hundreds Let’s see what each area and place has to offer and find the of streams of groundwater Karuizawa Shaw fall down on curved rock best choices matching your interests best. -

Where Are You HEADING? LONDON CALLING CELEBRATING the UK, OLYMPIC STYLE BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS SHARP MINDS and MBAS

tokyo JULY 2012 weekenderJapan’s premier English language magazine Since 1970 PLUS HERE COMES KARUIZAWA MOUNTAIN ESCAPE THE SUMMER OF THE STARS WHERE ARE you HEADING? LONDON CALLING CELEBRATING THE UK, OLYMPIC STYLE BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS SHARP MINDS AND MBAS INTERVIEWS Top UK Designers AGENDA M O V I E S Sir Paul Smith and Cath Kidston talk to All the biggest shows Previews of the best movies Weekender & events in July coming up this month ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: The Latest APAC news from the Asia Daily Wire, People Parties & Places with Bill Hersey and much more... ilan_baski_tokyo.pdf 1 6/26/12 11:33 AM Europe’s Best Airline FLY WITH TURKISH AIRLINES TO MORE THAN 200 DESTINATIONS VIA ISTANBUL C M Y CM MY CY CMY K turkishairlines.com ilan_baski_tokyo.pdf 1 6/26/12 11:33 AM Europe’s Best Airline FLY WITH TURKISH AIRLINES TO MORE THAN 200 DESTINATIONS VIA ISTANBUL C M Y CM MY CY CMY K turkishairlines.com JULY 2012 CONTENTS 22 HOT HOT SUMMER A few tips on how to make the most of the scorching months to come. 12 18 24 PAUL SMITH Interview CATH KIDSTON KARUIZAWA This super-cool British designer is as We spoke to he Queen of floral print about John Lennon loved it, the Emperor stays down to earth as they come. her new cafe in Kanagawa. there... what more do you need? 11 Asia Daily Wire 20 Served to Perfection 44 Agenda A roundup of all the top APAC news of the The spirit of omotenashi and why service in Fuji Rock Festival and all the best Tokyo past month. -

Itinerary 7/21/2019 Koyasan & Nakasendo Way Walk

Koyasan & Nakasendo Way Walk April 21‐May 5, 2020 Leaders: Kris Ashton and Christine Petty from $4140 Magome, one of 11 post‐towns of the Nakasendo Way that we will pass through Spring is an amazing time to be in Japan! The cherry blossoms in Japan are some of the most beautiful in the world. Our trip is timed to visit key locations at the height of the cherry blossom displays, in both Koyasan and along the Nakasendo Way. Our trip starts in the city of Osaka where we’ll have an opportunity to explore the energetic Dotonbori neighborhood before heading up the mountain to Koyasan. Koyasan is a complex of over 100 individual temples dedicated to the study and practice of Shingon Buddhism, brought to Japan in 819 by Kobo Daishi. We’ll stay at one of the temples where we’ll be taken care of by the monks who live there. At the temple, we can enjoy meditation practice, experience sutra writing or just relax in the hot bath or beautiful gardens. We’ll explore Koyasan with a knowledgeable local guide and participate in making our own decorative sushi as part of our lunch. We’ll hike along a rugged mountain route once allocated to women pilgrims. The Nakasendō Way (中山道 Central Mountain Route), also called the Kisokaidō, was one of two routes that connected Edo (modern‐day Tokyo) to Kyoto in Japan. There were 69 stations (staging‐posts or post‐ towns) between Edo and Kyoto, established for the purpose of providing a resting place for travelers along the road. -

Toshiji Takatsu

High-Speed Railways in Asia ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Toshiji Takatsu Introduction construction, development of shinkansen technology and the characteristics and impact of the shinkansen, as well The Tokaido Shinkansen entered revenue service as the as future systems. world’s first full-scale high-speed railway system on 1 October 1964, just in time for the opening of the Tokyo 1964 XVIII Olympics. Since then, the shinkansen has Japan and High-Speed Railways played an important role in Japanese business and leisure Geography travel, becoming the world benchmark for high-speed Japan is a long, thin archipelago at the edge of Eurasia transport and carrying 2173 billion passenger-km in speed on the Pacific Ocean. It is comprised of the four main and safety. The shinkansen is also heralded for reversing islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu and Shikoku, plus the decline of railways in the face of increasing road and more than 3000 smaller islands. About 73% of the total air travel and creating a new era of high-speed railway travel. land area is mountainous and the main centres of Shinkansen technology has developed in line with Japan’s population for the 127 million Japanese are on the coastal social and economic changes and has seen rising speeds, plain or bordering rivers. As a result, the cities along the cost savings, and safety, as well as falling environmental coastal plain have high population densities and are impact. Following the JNR privatization and division, a linked by railways. Sitting on the Pacific Rim of Fire, new shinkansen construction plan has seen the network Japan is very volcanic with severe geological, geographic, expand while each regional operator in the JR group has and climatic conditions; volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, developed new trains and improved infrastructure landslides, tsunamis, typhoons, and heavy snowfalls are targeted at increased speeds and enhanced services based all frequent. -

From Narita International Airport from Haneda Airport Transportation Guide There Sa Never-Ending List of Fun, Memorable E

▼ Shima Onsen ▶ Mount Tanigawa ◀ Ozegahara Shima is celebrated as “the spring of Straddling the border Oze is one of the precious What is the GuGutto GUNMA Tourism Campaign? beauties.” This onsen town is full of simple, between Gunma and few remaining nostalgic charm. A famous event known as Niigata prefectures, this is The GuGutto GUNMA Tourism Campaign is a public-relations high-altitude wetlands. It's the “Chochin (Paper Lantern) Walk” is held counted as one of Japan’s a world rich in the variety program designed to spread the word about Gunma’s many here, in which people walk through the hundred most famous of rare living things, attractions, showing people all the excitement there is to town swinging paper lanterns in one hand. mountains. Mount including mountain plants discover in Gunma. Tanigawa’s rock walls, and insects. The grandeur The campaign is packed with new experiences and a variety of including Ichinokurasawa, and refreshing atmosphere are among the three most are a pleasure to witness. events. Come and taste the charms of Gunma! notable rock formations in Japan, and are considered Here’s what’s behind the theme, “GuGutto GUNMA ‒ Discover to be the Mecca of exciting new experiences.”: Japanese rock climbing. From trekking to full-blown We would like everyone to get mountain climbing, there excited with visiting attractive are many ways to enjoy spots and events in Gunma and Mount Tanigawa. ▼ Kusatsu Onsen have memorable experiences that Kusatsu is one of Japan’s most renowned get to your heart. onsen resorts, boasting the highest amount of natural hot water discharge of Oze any onsen resorts in the country. -

Ukiyo-E Produkte Katalog

Ukiyo-e Roman & Daniela Jost, Asiatische Möbel, Ukiyo-e, Ikebana und Steinlaternen, Huebwiesenstrasse 52a, CH-8954 Geroldswil Tel. 044 747 03 71 E-Mail: [email protected] www.japankunst.ch 16.04.2021 Seite 1 von 20 Roman & Daniela Jost, Asiatische Möbel, Ukiyo-e, Ikebana und Steinlaternen, Huebwiesenstrasse 52a, CH-8954 Geroldswil Tel. 044 747 03 71 E-Mail: [email protected] www.japankunst.ch Ukiyo-e, Holzdruck im vormodernen Japan Im vormodernen Japan spiegelt sich das Leben in den ukiyo-e benannten Holzschnitten wieder, die dem Betrachter das bunte Treiben "der fliessenden Welt vermitteln". Die Holzdruck-Technik kam bereits im 8. Jahrhundert mit dem Buddhismus aus China nach Japan, doch diente sie zunächst religiösen Zwecken. Erst mit dem Aufblühen der bürgerlichen Kultur seit dem Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts eroberten die profanen wie auch frivolen Themen den Bilddruck. In Japan berühmt, ist die Geschichte des verarmten Samurai, der in einer bitterkalten Winternacht des Jahres 1383 seine letzten drei geliebten Bonsai dem Feuer opferte, um für seinen hohen Besuch, einen Shogun, zu heizen. Auf diesem Holzdruck ist zu sehen, wie die Bäumchen gerade mit einem Haumesser abgeschlagen werden. Herstellung von Holzdrucken Beim Holzdruck werden die zu druckenden Teile aus dem Druckträger erhaben herausgearbeitet. Man verwendet für den Holzschnitt mit Vorliebe ein Langholz vom Obstbaum (Birnbaum- oder Kirschenholz). Darauf wird die Zeichnung aufgetragen und mit dem Messer herausgeschnitten. Die nicht druckenden Teile werden weg geschnitten, so dass die Zeichnung schliesslich erhaben auf dem Block steht. Auf das eingefärbte Relief wird ein angefeuchtetes Papier gelegt, das mit der Hand angerieben oder durch die Buchpresse angedrückt wird.