Cultural China: the Periphery As the Center Author(S): Tu Wei-Ming Source: Daedalus, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnography of the Spring Festival

IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY, AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Li Ren June 2003 This dissertation entitled IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL BY LI REN has been approved by the School of Interpersonal Communication and the College of Communication by Arvind Singhal Professor of Interpersonal Communication Timothy A. Simpson Professor of Interpersonal Communication Kathy Krendl Dean, College of Communication REN, LI. Ph.D. June 2003. Interpersonal Communication Imagining China in the Era of Global Consumerism and Local Consciousness: Media, Mobility, and the Spring Festival. (260 pp.) Co-directors of Dissertation: Arvind Singhal and Timothy A. Simpson Using the Spring Festival (the Chinese New Year) as a springboard for fieldwork and discussion, this dissertation explores the rise of electronic media and mobility in contemporary China and their effect on modern Chinese subjectivity, especially, the collective imagination of Chinese people. Informed by cultural studies and ethnographic methods, this research project consisted of 14 in-depth interviews with residents in Chengdu, China, ethnographic participatory observation of local festival activities, and analysis of media events, artifacts, documents, and online communication. The dissertation argues that “cultural China,” an officially-endorsed concept that has transformed a national entity into a borderless cultural entity, is the most conspicuous and powerful public imagery produced and circulated during the 2001 Spring Festival. As a work of collective imagination, cultural China creates a complex and contested space in which the Chinese Party-state, the global consumer culture, and individuals and local communities seek to gain their own ground with various strategies and tactics. -

Burro Burro Phd

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI TRIESTE Sede Amministrativa del Dottorato di Ricerca IUAV – ISTITUTO UNIVERSITARIO DI ARCHITETTURA DI VENEZIA, UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI FERRARA, UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI UDINE, UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI SALERNO, UNIVERSITA’ DEL PIEMONTE ORIENTALE “AMEDEO AVOGADRO” NOVARA, UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DEL SANNIO – BENEVENTO, UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI MESSINA, UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “FEDERICO II”, UNIVERSITA’ PRIMORSKA DI KOPER, UNIVERSITA’ DI KLANGEFURT, UNIVERSITA’ DI MALTA Sedi Convenzionate SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE DELL’UOMO, DEL TERRITORIO E DELLA SOCIETA’ INDIRIZZO IN GEOPOLITICA, GEOSTRATEGIA E GEOECONOMIA - XXIII CICLO (SETTORE SCIENTIFICO-DISCIPLINARE M-GGR/02) LA REPUBBLICA POPOLARE CINESE TRA NECESSITA’ ED AMBIZIONE DI UN’ADEGUATA STRATEGIA GEO-CULTURALE DOTTORANDO RELATORE Dott. ANDREA BURRO Chiar.ma Prof.ssa MARIA PAOLA PAGNINI Università degli Studi “Niccolò Cusano” - Telematica ANNO ACCADEMICO 2009-2010 Verschlossnen Augs, ihr Wunder nicht zu schauen, durchzog ich blind Italiens holde Auen. R. Wager, Tannhäuser. 2 INDICE INTRODUZIONE 5 LA CINA LABORATORIO DI NARRAZIONI GEOGRAFICHE IN BILICO FRA TRADIZIONE ED INNOVAZIONE 1.1 Falso immobilismo e miti fondatori 11 1.2 Evoluzione dell’impero cinese: centralizzazione e frammentazione 14 1.2.1 Dalle origini all’epoca dei Tre Regni 14 1.2.2 Dalla dinastia Tang alla dinastia Song 20 1.2.3 Dalla dinastia Yuan alla dinastia Qing 24 1.3 L’incontro con l’Occidente: crisi e tentativi di modernizzazione 36 1.3.1 Il pendolo della storia: -

Confucianism, "Cultural Tradition" and Official Discourses in China at the Start of the New Century

China Perspectives 2007/3 | 2007 Creating a Harmonious Society Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century Sébastien Billioud Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Sébastien Billioud, « Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/3 | 2007, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2010, consulté le 14 novembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 © All rights reserved Special feature s e v Confucianism, “Cultural i a t c n i e Tradition,” and Official h p s c r Discourse in China at the e p Start of the New Century SÉBASTIEN BILLIOUD This article explores the reference to traditional culture and Confucianism in official discourses at the start of the new century. It shows the complexity and the ambiguity of the phenomenon and attempts to analyze it within the broader framework of society’s evolving relation to culture. armony (hexie 和谐 ), the rule of virtue ( yi into allusions made in official discourse, we are interested de zhi guo 以德治国 ): for the last few years in another general and imprecise category: cultural tradi - Hthe consonance suggested by slogans and tion ( wenhua chuantong ) or traditional cul - 文化传统 themes mobilised by China’s leadership has led to spec - ture ( chuantong wenhua 传统文化 ). ((1) However, we ulation concerning their relationship to Confucianism or, are excluding from the domain of this study the entire as - more generally, to China’s classical cultural tradition. -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

Download the Full Issue

East Asian History NUMBER 41 • AUGUST 2017 www.eastasianhistory.org CONTENTS 1–2 Guest Editor’s Preface Shih-Wen Sue Chen 3–14 ‘Aspiring to Enlightenment’: Buddhism and Atheism in 1980s China Scott Pacey 15–24 Activist Practitioners in the Qigong Boom of the 1980s Utiraruto Otehode and Benjamin Penny 25–40 Displaced Fantasy: Pulp Science Fiction in the Early Reform Era of the People’s Republic Of China Rui Kunze 王瑞 41–48 The Emergence of Independent Minds in the 1980s Liu Qing 刘擎 49–56 1984: What’s Been Lost and What’s Been Gained Sang Ye 桑晔 57–71 Intellectual Men and Women in the 1980s Fiction of Huang Beijia 黄蓓佳 Li Meng 李萌 online Chinese Magazines of the 1980s: An Online Exhibition only Curated by Shih-Wen Sue Chen Editor Benjamin Penny, The Australian National University Guest Editor Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Deakin University Editorial Assistant Lindy Allen Editorial Board Geremie R. Barmé (Founding Editor) Katarzyna Cwiertka (Leiden) Roald Maliangkay (ANU) Ivo Smits (Leiden) Tessa Morris-Suzuki (ANU) Design and production Lindy Allen and Katie Hayne Print PDFs based on an original design by Maureen MacKenzie-Taylor This is the forty-first issue of East Asian History, the fourth published in electronic form, August 2017. It continues the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. Contributions to www.eastasianhistory.org/contribute Back issues www.eastasianhistory.org/archive To cite this journal, use page numbers from PDF versions ISSN (electronic) 1839-9010 Copyright notice Copyright for the intellectual content of each paper is retained by its author. -

Open Dissertation FINAL2.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications AFTER A RAINY DAY IN HONG KONG: MEDIA, MEMORY AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, A LOOK AT HONG KONG’S 2014 UMBRELLA MOVEMENT A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Kelly A. Chernin © 2017 Kelly A. Chernin Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 The dissertation of Kelly A. Chernin was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew F. Jordan Associate Professor of Media Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee C. Michael Elavsky Associate Professor of Media Studies Michelle Rodino-Colocino Associate Professor of Media Studies Stephen H. Browne Liberal Arts Research Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Ford Risley Professor of Communications Associate Dean of the College of Communications *Signatures are on file in the graduate school. ii ABSTRACT The period following an occupied social movement is often overlooked, yet it is an important moment in time as political and economic systems are potentially vulnerable. In 2014, after Hong Kong’s Chief Executive declared that the citizens of Hong Kong would be unable to democratically elect their leader in the upcoming 2017 election, a 79-day occupation of major city centers ensued. The memory of the three-month occupation, also known as the Umbrella Movement was instrumental in shaping a political identity for Hong Kong’s residents. Understanding social movements as a process and not a singular event, an analytic mode that problematizes linear temporal constructions, can help us move beyond the deterministic and celebratory views often associated with technology’s role in social movement activism. -

Master´S Thesis 2020 Bc. Denisa Máchová

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Chinese Studies Master´s Thesis 2020 Bc. Denisa Máchová Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Chinese Studies Cultural Studies of China Bc. Denisa Máchová The Self – loathing Discourse in the Theme of Modernisation in the Chinese Literature of the 20th Century Master´s Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. et Mgr. Dušan Vávra, Ph.D. 2020 I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and it contains no other materials written or published by any other person except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. Brno, May 2020 …..…………………… The thesis was completed within the cooperation framework between the Department of Chinese Studies (Masaryk University) and the Institute of China Studies (Zhejiang University). During my two- semester stay in China, the thesis was supervised by Prof. Jiang Wentao 姜文涛, Associate Professor in School of International Studies at Zhejiang University, China. ABSTRACT This thesis elaborates the self-loathing discourse in the theme of modernization in 20th century Chinese literature. The main question is how the discourse of self-loathing is elaborated in chosen works from the 20th century and how is it evolving during this century. This work is divided into four chapters. The first one contains the definition of self-loathing, the presentation of main historical events of the 20th century and philosophical changes in Chinese society during the 20th century. The second chapter presents the authors, their lives, creation, writing style and general attitude towards modernisation of Chinese society. The third chapter contains the discourse analysis of chosen literature works and presents the concrete examples of discourse of self-loathing, which were found. -

Capital Dreams: Global Consumption, Urban Imagination, And

©2009 Ju-chen Chen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION CAPITAL DREAMS: GLOBAL CONSUMPTION, URBAN IMAGINATION, AND LABOR MIGRATION IN LATE SOCIALIST BEIJING By JU-CHEN CHEN Dissertation Director: Louisa Schein This dissertation addresses the remaking of Beijing, with a focus on social differentiations within and beyond the city, under the impacts of the late socialist Chinese state and the expansion of global capitalism in the early 2000s. It is argued that the early 2000s witnessed China transforming from being external-referencing to self-referencing. This research simultaneously investigated the city in global, national and local contexts. Multi-site ethnographic research was performed and a design of multiple informant groups was employed. This dissertation focused on Beijing, but included perspectives external to Beijing. Beijing was the main field site, but extensive ethnographic fieldwork was also conducted in Xi’an, together with several shorter research trips to various locations. Shifting perspectives within and outside of Beijing offered insights into how the physical place of Beijing is variously imagined and created. New social groups are emerging in Beijing during the Economic Reform era, and Beijing is a different place for every distinct group of inhabitants, meaning conclusions about Beijing depend on “whose Beijing” one is addressing. This dissertation focuses on three economically-differentiated ii informant groups in the emergent social hierarchy of Beijing: a new privileged elite of business professionals, a poor working class of native Beijingers, and a new marginalized underclass of migrant laborers. The dynamics among these groups are examined through their consumption practices and use of mass media because these two domains of daily practice are crucial for identity negotiation in late socialist China. -

Intellectual Effervescence in China Author(S): Tu Wei-Ming Source: Daedalus, Vol

Intellectual Effervescence in China Author(s): Tu Wei-ming Source: Daedalus, Vol. 121, No. 2, The Exit from Communism (Spring, 1992), pp. 251-292 Published by: The MIT Press on behalf of American Academy of Arts & Sciences Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20025441 Accessed: 10-05-2019 02:54 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Academy of Arts & Sciences, The MIT Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Daedalus This content downloaded from 222.29.122.77 on Fri, 10 May 2019 02:54:52 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Tu Wei-ming Intellectual Effervescence in China The disintegration of the union of the Soviet Socialist Republics and the r?int?gration of the European Community pose intriguing questions about the new world order. The apparent triumph of the market economy and democratic polity may suggest that the bitter struggle between capitalism and socialism is ending. The emergence of a victorious West signals the end of the Cold War. The simple military victory in the Gulf War may have enhanced the impression that the United States, the unrivaled leader of the Western world, is now the most powerful shaper of the new world order. -

Untitled by Hung Chang (C

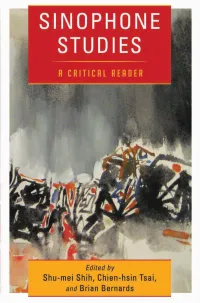

SINOPHONE STUDIES Global Chinese Culture GLOBAL CHINESE CULTURE David Der-wei Wang, Editor Michael Berry, Speaking in Images: Interviews with Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers Sylvia Li-chun Lin, Representing Atrocity in Taiwan: The 2/28 Incident and White Terror in Fiction and Film Michael Berry, A History of Pain: Literary and Cinematic Mappings of Violence in Modern China Alexander C. Y. Huang, Chinese Shakespeares: A Century of Cultural Exchange SINO ______________PHONE STUDIES A Critical Reader edited by SHU-MEI SHIH, CHIEN-HSIN TSAI, and BRIAN BERNARDS Columbia University Press New York Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Chiang Ching- kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange and Council for Cultural Affairs in the publication of this book. Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright © 2013 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sinophone studies : a critical reader / edited by Shu-mei Shih, Chien-hsin Tsai, and Brian Bernards. p. cm.—(Global Chinese culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-231-15750-6 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-231-15751-3 (pbk.)— ISBN 978-0-231-52710-1 (electronic) 1. Chinese diaspora. 2. Chinese–Foreign countries–Ethnic identity. 3. Chinese–Foreign countries– Intellectual life. 4. National characteristics, Chinese. I. Shi, Shumei, 1961–II. Tsai, Chien-hsin, 1975– III. Bernards, Brian. DS732.S57 2013 305.800951–dc23 2012011978 Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. This book was printed on paper with recycled content. -

Culture Fever: Utopianism and Pragmatism in Chinese Intellectuals' Search for Modernization Gao Yijia Pomona

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont 2018 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award Research Award 4-26-2018 Culture Fever: Utopianism and Pragmatism in Chinese Intellectuals' Search for Modernization Gao Yijia Pomona Hu Pengbo Pomona Jacob Waldor Pomona Wang Zelin Pomona Recommended Citation Yijia, Gao; Pengbo, Hu; Waldor, Jacob; and Zelin, Wang, "Culture Fever: Utopianism and Pragmatism in Chinese Intellectuals' Search for Modernization" (2018). 2018 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award. 5. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cclura_2018/5 This Group Award Winner is brought to you for free and open access by the Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2018 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2018 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award Group Award Winner Wang Zelin Jacob Waldor Gao Yijia Hu Pengbo Pomona College Reflective Essay Group Reflection: The inspiration of the research is twofold: Professor Allan H. Barr's Pomona Freshman writing seminar titled China from Inside and Out and 5C's newly founded Contemporary Chinese Literature Discussion Club. Professor Barr's class exposed students to a broad range of literature on Chinese experiences. Captivated by the dichotomy of "the West and the East", which permeates numerous texts, Zelin and Yijia decided to further examine how Chinese people grappled with the often conflicting relations between Westernization and Chinese traditions as well as the sudden advent of modernity and the loss of egalitarian society by initiating the Contemporary Chinese Literature Discussion Club. -

SUN YAT-SENS: CONTESTED IMAGES of a POLITICAL ICON By

SUN YAT-SENS: CONTESTED IMAGES OF A POLITICAL ICON by THOMAS EVAN FISCHER A THESIS Presented to the Asian Studies Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2020 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Thomas Evan Fischer Title: Sun Yat-sens: Contested Images of a Political Icon This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Asian Studies Program by: Bryna Goodman Chairperson Ina Asim Member Daniel Buck Member and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2020 ii © 2020 Thomas Evan Fischer iii THESIS ABSTRACT Thomas Evan Fischer Master of Arts Asian Studies Program September 2020 Title: Sun Yat-sens: Contested Images of a Political Icon This thesis explores the afterlives of the Chinese revolutionary icon Sun Yat- sen and their relevant contexts, arguing that these contexts have given rise to different images of the same figure. It serves as a gallery in which these different images are put into conversation with one another, revealing new insights into each. Key to the discussion, Sun is first introduced in a short biography. Then, the thesis moves to his different afterlives: Sun and the fight for his posthumous approval in the Republic of China before 1949; Sun and his usage in Chinese Communist political rhetoric from 1956 through 2016; Sun and his changing image in the ROC-Taiwan, a change that reflects the contentious political environment of an increasingly bentu Taiwan; Sun and two of his images among the overseas Chinese of Hawaii and Penang.