Maya, Tradition and Modernity in Shaji Karun's Vaanaprastham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIARA Research Final-Online

TIARAResearch Insight Based Research Across Celebrities Indian Institute of Human Brands 2020 About IIHBThe Indian Institute of Human Brands (IIHB) has been set up by Dr. Sandeep Goyal, India’s best known expert in the domain of celebrity studies. Dr. Goyal is a PhD from FMS-Delhi and has been researching celebrities as human brands since 2003. IIHB has many well known academicians and researchers on its advisory board ADVISORY Board D. Nandkishore Prof. ML Singla Former Global Executive Board Former Dean Member - Nestlé S.A., Switzerland FMS Delhi Dr. Sandeep Goyal Chief Mentor Dr. Goyal is former President of Rediffusion, ex-Group CEO B. Narayanaswamy Prof. Siddhartha Singh of Zee Telefilms and was Founder Former Managing Director Associate Professor of Marketing Chairman of Dentsu India IPSOS and Former Senior Associate Dean, ISB 0 1 WHY THIS STUDY? Till 20 years ago, use of a celebrity in advertising was pretty rare, and quite much the exception Until Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC) happened almost 20 years ago, top Bollywood stars would keep their distance from television and advertising In the first decade of this century though use of famous faces both in advertising as well as in content creation increased considerably In the last 10 years, the use of celebrities in communication has increased exponentially Today almost 500 brands, , big and small, national and regional, use celebrities to endorse their offerings 0 2 WHAT THIS STUDY PROVIDES? Despite the exponential proliferation of celebrity usage in advertising and content, WHY there is no organised body of knowledge on these superstars that can help: BEST FIT APPROPRIATE OR BEST FIT SELECTION COMPETITIVE CHOOSE BETTER BETWEEN BEST FITS PERCEPTION CHOOSE BASIS BRAND ATTRIBUTES TRENDY LOOK AT EMERGING CHOICES FOR THE FUTURE 0 3 COVERAGE WHAT 23 CITIES METRO MINI METRO LARGE CITIES Delhi Ahmedabad Nagpur (incl. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

JANUARY 2016 .Com/Civilsocietyonline `50

VOL. 13 NO. 3 JANUARY 2016 www.civilsocietyonline.com .com/civilsocietyonline `50 ssttrreeeett bbuussiinneessss How NASVI helps vendors upscale Arbind Singh, National Coordinator of NASVI anil swarup on coal SPECIAL FOCUS entering rural markets Pages 9-10 Delhi comes Pages 22-23 fat girls are smart low status of teachers Page 14 full circle on Pages 25-26 air pollution chilD health sinks the kerala film fest Page 15 Pages 6-8 Pages 29-31 ConTenTS READ U S. WE READ YO U. give vendors their due enDorS work hard and brave many odds to earn a living. They deserve to be given their due as entrepreneurs. Small businesses like Vtheirs are tough to run and have all the challenges of providing quality and value to customers. From their carts and stalls they derive incomes on which their families depend. It is estimated that there are 10 million vendors in the country. It would be impossible to replace so many livelihoods. efforts to push them off the streets are misconceived and a vio - coVer storY lation of their rights. Vendors also add colour and diversity to our cities and towns with their range of wares and food items. They are essential to an street business urban mosaic. It is fortunate that a central law passed in 2014 bestows recognition on india has an estimated 10 million street vendors who earn a living vending. Credit for getting the law passed by Parliament must go to nASVI selling wares and serving up meals. They are a uniquely plural or the national Association of Street Vendors of India. -

Music in South India – Kerala a Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed By: Lum Chee Hoo University of Washington

Music in South India – Kerala A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Lum Chee Hoo University of Washington Summary: Talk about the geography, language, and culture of Kerala in South India using story songs, dance dramas, and rhythms. Introduce students to specific artists and instruments important to Kerala's musical traditions. Suggested Grade Levels: 9-12 Country: India Region: Asia Culture Group: Kerala Genre: Indian Instruments: Voice Language: Malayalam Co-Curricular Areas: Social Studies National Standards: 6, 9 Prerequisites: None Objectives: Learn about culture of Kerala group, including music, dance, and language Materials: “Idakka” from Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://www.folkways.si.edu/tr-ankaran-nambudiri-and-pm-narayana- mara/idakka/world/music/track/smithsonian “Nala Charitam,” Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://www.folkways.si.edu/mep-pillai-and-gopinathan-nayar-k-damodaran- pannikar-and-vasudeva-poduwal-mankulam-vishnu-nambudiri-and-kudama-ur- karunakaran-nayar/kathakai-nala-charitam/world/music/track/smithsonian “Panchawadyam” from Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://www.folkways.si.edu/instrumental/panchawadyam/world/music/track/s mithsonian http://www.folkways.si.edu/narayana-mara-and- party/panchawadyam/world/music/track/smithsonian Liner notes from Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://media.smithsonianfolkways.org/liner_notes/folkways/FW04365.pdf The JVC video anthology of world music and dance: South Asia I, India, Track 11- 2 (Kathakali-dance-drama: Dryodana vadham from the Mohabharata DVD - Vanaprastham: The last dance (1999). Director: Shaji N. Karun. Vanguard Cinema. ASIN: B000066C7A Map of South India Pictures of instruments: from liner notes and Music in South India: Experiencing music, expressing culture Lesson Segments: 1. -

Postcolonial Pirate Domain." Postcolonial Piracy: Media Distribution and Cultural Production in the Global South

Poduval, Satish. "Hacking and Difference: Reflections on Authorship in the Postcolonial Pirate Domain." Postcolonial Piracy: Media Distribution and Cultural Production in the Global South. Ed. Lars Eckstein and Anja Schwarz. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 273–292. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472519450.ch-012>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 06:23 UTC. Copyright © Lars Eckstein and Anja Schwarz 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 12 Hacking and Difference Reflections on Authorship in the Postcolonial Pirate Domain Satish Poduval Philip K. Dick famously observed about science fiction that ‘Jules Verne’s story of travel to the moon is not SF because they go by rocket but because of where they go. It would be as much SF if they went by rubber band’ (Dick 1995: 57). A remark like that is peculiarly resonant in postcolonial spaces where historical experience tends to be framed as a story of travel, as a destinal narrative1 in which modernity is simul- taneously a destination to be reached and the ensemble of mechanisms destined to accelerate the journey. However, in recent decades, the helical loop of this narrative appears to be unravelling. Neither the vision nor the vehicle of modernization is any longer monopolized by the state or the older national elites, and earlier conceptions of a shared Third World identity forged by imperial exploitation and industrial backwardness do not typify the global South uniformly today. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21St Century

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21st Century Neelam Sidhar Wright For my parents, Kiran and Sharda In memory of Rameshwar Dutt Sidhar © Neelam Sidhar Wright, 2015 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9634 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9635 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0356 6 (epub) The right of Neelam Sidhar Wright to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents Acknowledgements vi List of Figures vii List of Abbreviations of Film Titles viii 1 Introduction: The Bollywood Eclipse 1 2 Anti-Bollywood: Traditional Modes of Studying Indian Cinema 21 3 Pedagogic Practices and Newer Approaches to Contemporary Bollywood Cinema 46 4 Postmodernism and India 63 5 Postmodern Bollywood 79 6 Indian Cinema: A History of Repetition 128 7 Contemporary Bollywood Remakes 148 8 Conclusion: A Bollywood Renaissance? 190 Bibliography 201 List of Additional Reading 213 Appendix: Popular Indian Film Remakes 215 Filmography 220 Index 225 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the following people for all their support, guidance, feedback and encouragement throughout the course of researching and writing this book: Richard Murphy, Thomas Austin, Andy Medhurst, Sue Thornham, Shohini Chaudhuri, Margaret Reynolds, Steve Jones, Sharif Mowlabocus, the D.Phil. -

Été Indien 10E Édition 100 Ans De Cinéma Indien

Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien 9 Les films 49 Les réalisateurs 10 Harishchandrachi Factory de Paresh Mokashi 50 K. Asif 11 Raja Harishchandra de D.G. Phalke 51 Shyam Benegal 12 Saint Tukaram de V. Damle et S. Fathelal 56 Sanjay Leela Bhansali 14 Mother India de Mehboob Khan 57 Vishnupant Govind Damle 16 D.G. Phalke, le premier cinéaste indien de Satish Bahadur 58 Kalipada Das 17 Kaliya Mardan de D.G. Phalke 58 Satish Bahadur 18 Jamai Babu de Kalipada Das 59 Guru Dutt 19 Le vagabond (Awaara) de Raj Kapoor 60 Ritwik Ghatak 20 Mughal-e-Azam de K. Asif 61 Adoor Gopalakrishnan 21 Aar ar paar (D’un côté et de l’autre) de Guru Dutt 62 Ashutosh Gowariker 22 Chaudhvin ka chand de Mohammed Sadiq 63 Rajkumar Hirani 23 La Trilogie d’Apu de Satyajit Ray 64 Raj Kapoor 24 La complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) de Satyajit Ray 65 Aamir Khan 25 L’invaincu (Aparajito) de Satyajit Ray 66 Mehboob Khan 26 Le monde d’Apu (Apur sansar) de Satyajit Ray 67 Paresh Mokashi 28 La rivière Titash de Ritwik Ghatak 68 D.G. Phalke 29 The making of the Mahatma de Shyam Benegal 69 Mani Ratnam 30 Mi-bémol de Ritwik Ghatak 70 Satyajit Ray 31 Un jour comme les autres (Ek din pratidin) de Mrinal Sen 71 Aparna Sen 32 Sholay de Ramesh Sippy 72 Mrinal Sen 33 Des étoiles sur la terre (Taare zameen par) d’Aamir Khan 73 Ramesh Sippy 34 Lagaan d’Ashutosh Gowariker 36 Sati d’Aparna Sen 75 Les éditions précédentes 38 Face-à-face (Mukhamukham) d’Adoor Gopalakrishnan 39 3 idiots de Rajkumar Hirani 40 Symphonie silencieuse (Mouna ragam) de Mani Ratnam 41 Devdas de Sanjay Leela Bhansali 42 Mammo de Shyam Benegal 43 Zubeidaa de Shyam Benegal 44 Well Done Abba! de Shyam Benegal 45 Le rôle (Bhumika) de Shyam Benegal 1 ] Je suis ravi d’apprendre que l’Auditorium du musée Guimet organise pour la dixième année consécutive le festival de films Été indien, consacré exclusivement au cinéma de l’Inde. -

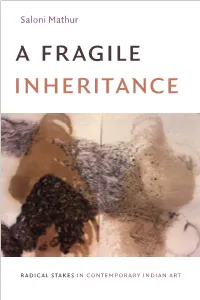

A Fragile Inheritance

Saloni Mathur A FrAgile inheritAnce RadicAl StAkeS in contemporAry indiAn Art Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian Art ·· · 2019 © 2019 All rights reserved Printed in the United States o America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Quadraat Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library o Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Mathur, Saloni, author. Title: A fragile inheritance : radical stakes in contemporary Indian art / Saloni Mathur. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identi£ers: ¤¤ 2019006362 (print) | ¤¤ 2019009378 (ebook) « 9781478003380 (ebook) « 9781478001867 (hardcover : alk. paper) « 9781478003014 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: ¤: Art, Indic—20th century. | Art, Indic—21st century. | Art—Political aspects—India. | Sundaram, Vivan— Criticism and interpretation. | Kapur, Geeta, 1943—Criticism and interpretation. Classi£cation: ¤¤ 7304 (ebook) | ¤¤ 7304 .384 2019 (print) | ¤ 709.54/0904—dc23 ¤ record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006362 Cover art: Vivan Sundaram, Soldier o Babylon I, 1991, diptych made with engine oil and charcoal on paper. Courtesy o the artist. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the ¤ Academic Senate, the ¤ Center for the Study o Women, and the ¤ Dean o Humanities for providing funds toward the publication o this book. ¶is title is freely available in an open access edition thanks to the initiative and the generous support o Arcadia, a charitable fund o Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, and o the ¤ Library. vii 1 Introduction: Radical Stakes 40 1 Earthly Ecologies 72 2 The Edice Complex 96 3 The World, the Art, and the Critic 129 4 Urban Economies 160 Epilogue: Late Styles 185 211 225 I still recall my £rst encounter with the works o art and critical writing by Vivan Sundaram and Geeta Kapur that situate the central concerns o this study. -

B.A Multimedia Examination (Cbcss)

BA Multimedia Semester IV Model Questions & Question Bank www.StudyGuideIndia.com B.A MULTIMEDIA EXAMINATION (CBCSS) SEMESTER IV Paper 4-1 SCENIC DESIGN: FILM & TELEVISION I (THEORY) Model Question -I Time: Three Hours Maximum Weight: 25 Part A Answer all questions. Each bunch of 4 questions carries weight 1 Answer in one word, phrase or sentence I. 1. The Dharma-Chakra devised by the Buddhists represents …………… 2. …………is generally considered the Golden age of Indian literature and art. 3. The term 'Chaitya' indicates that it is a place of ……………………… 4. The art of the Roman world is said to have directly inspired the productions of …………………. II. 5. What is the essential difference between the Gandhara and Mathura schools of art? 6. Which architectural monument is said to possess the largest domical roof in existence anywherewww.StudyGuideIndia.com in the world? 7. Name the mausoleum of Shah Jahan's beloved wife. 8. What is the central theme of Rajasthani painting? III. 9. What are set props? 10. What are cycloramas? 11. Who is considered the father of Indian theatrical arts? 12. Name a play written by Shakespeare IV. 13. Who is Dionysus? 14. Which Greek Dramatist is supposed to have added the second actor? 15. Name the author of Oedipus the King. 16. Name the term used in general to describe any drawing showing the physical layout of objects. (4 x 1= 4) Part B Short answer questions. Weight one each. Answer any five of the following 17. Write the fundamental characteristics which differentiate the art form of India from that of the Europeans.