A Commentary on the Management of Total Laryngectomy Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 and Neonatal Respiratory Care: Current Evidence and Practical Approach

Published online: 2020-05-02 780 Review Article COVID-19 and Neonatal Respiratory Care: Current Evidence and Practical Approach Wissam Shalish, MD1 Satyanarayana Lakshminrusimha, MD2 Paolo Manzoni, MD3 Martin Keszler, MD4 Guilherme M. Sant’Anna, MD, PhD, FRCPC1 1 Neonatal Division, Department of Pediatrics, McGill University Address for correspondence Guilherme M. Sant’Anna, MD, PhD, Health Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada FRCPC, Neonatal Division, Department of Pediatrics, McGill University 2 Department of Pediatrics, UC Davis, Sacramento, California Health Center, 1001 Décarie Boulevard, Room 05.2711, 3 Department of Pediatrics and Neonatology, University Hospital Montreal H4A 3J1, Canada (e-mail: [email protected]). Degli Infermi, Biella, Italy 4 Department of Pediatrics, Women and Infants Hospital, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island Am J Perinatol 2020;37:780–791. Abstract The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has urged the development and implementation of guidelines and protocols on diagnosis, management, infection control strategies, and discharge planning. However, very little is currently known about neonatal COVID-19 and severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections. Thus, many questions arise with regard to respiratory care after birth, necessary protection to health care workers (HCW) in the delivery room and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and safety of bag and mask ventilation, noninvasive respiratory support, deep suctioning, endotracheal intubation, and mechanical ventilation. Indeed, these questions have created tremendous confusion amongst neonatal HCW. In this manuscript, we comprehensively reviewed the current evidence regarding COVID-19 perinatal transmission, respiratory outcomes of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 and infants with documented SARS- CoV-2 infection, and the evidence for using different respiratory support modalities and aerosol-generating procedures in this specific population. -

COVID-19 and Total Laryngectomy—A Report of Two Cases

AORXXX10.1177/0003489420935500Annals of Otology, Rhinology & LaryngologyPaderno et al 935500case-report2020 Case Report Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 1 –4 COVID-19 and Total Laryngectomy © The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions —A Report of Two Cases DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489420935500 10.1177/0003489420935500 journals.sagepub.com/home/aor Alberto Paderno, MD1 , Milena Fior, MD1, Giulia Berretti, MD1, Francesca Del Bon, MD1, Alberto Schreiber, MD, PhD1, Alberto Grammatica, MD1, Davide Mattavelli, MD1, and Alberto Deganello, MD, PhD1 Abstract Objective: To date, no cases have been reported on the effects of COVID-19 in laryngectomees. Case Presentation: We herein presented two clinical cases of laryngectomized patients affected by COVID-19, detailing their clinical course and complications. Discussion: In our experience, permanent tracheostomy did not significantly affect the choice of treatment. However, dedicated devices and repeated tracheal toilettes may be needed to deal with oxygen-therapy-related tracheal crusting. Conclusion: In conclusion, laryngectomees should be considered a vulnerable population that may be at risk for worse outcomes of COVID-19 due to anatomical changes in their airways. The role of the ENT specialist is to guide airway management and inform the support-staff regarding specific needs of these patients. Keywords COVID-19, coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, laryngectomy, management Introduction At admission (March 9, 2020), the most relevant clinical findings included severe oxygen desaturation (76%), tachy- To date, the effects of COVID-19 on laryngectomized pnea, cyanosis, lymphocytopenia, and C reactive protein patients is unknown, with no cases reported so far. After (CRP; 185 mg/L). -

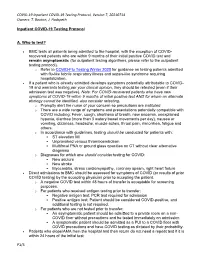

COVID 19 Inpatient Testing Guidelines

COVID-19 Inpatient COVID-19 Testing Protocol, Version 7, 20210714 Owners: T. Bouton, J. Hudspeth Inpatient COVID-19 Testing Protocol A. Who to test? BMC tests all patients being admitted to the hospital, with the exception of COVID- recovered patients who are within 9 months of their initial positive COVID test and remain asymptomatic (for outpatient testing algorithms, please refer to the outpatient testing protocol). o Refer to COVID-Flu Testing Winter 2020 for guidance on testing patients admitted with flu-like febrile respiratory illness and sepsis-like syndrome requiring hospitalization. If a patient who is already admitted develops symptoms potentially attributable to COVID- 19 and warrants testing per your clinical opinion, they should be retested (even if their admission test was negative). Note: For COVID-recovered patients who have new symptoms of COVID-19 within 9 months of initial positive test AND for whom an alternate etiology cannot be identified, also consider retesting. o Promptly alert the nurse of your concern so precautions are instituted o There are a wide range of symptoms and presentations potentially compatible with COVID including: Fever, cough, shortness of breath, new anosmia, unexplained hypoxia, diarrhea (more than 3 watery bowel movements per day), nausea or vomiting, dizziness, headache, muscle aches, throat pain, rhinorrhea, fatigue and others. o In accordance with guidelines, testing should be conducted for patients with: . ST elevation MI . Unprovoked venous thromboembolism . Multifocal PNA or ground glass opacities on CT without clear alternative diagnosis o Diagnoses for which one should consider testing for COVID: . New seizure . New stroke . Myocarditis, stress cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, right heart failure Direct admissions to BMC should be assessed for symptoms of COVID (or results of prior COVID testing) by the accepting physician prior to accepting the patient. -

Disparate Nasopharyngeal and Tracheal COVID-19 Diagnostic Test

Revised complete Manuscript Click here to access/download;Complete Manuscript;laryngectomy Testing manuscript plaintext.docx This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1 1 Disparate Nasopharyngeal and Tracheal COVID-19 Diagnostic Test 2 Results in a Patient with Total Laryngectomy 3 Running Title: “COVID-19 Testing with Total Laryngectomy” 4 5 Tirth R. Patel, MD1; Joshua E. Teitcher, CCC-SLP2; Bobby A. Tajudeen, MD1; Peter C. 6 Revenaugh, MD1 7 8 1. Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Rush University Medical 9 Center, Chicago, Illinois 10 2. Department of Hematology/Oncology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois 11 12 Corresponding Author: 13 Tirth R. Patel, MD 14 Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery 15 Rush University Medical Center 16 1650 West Harrison Street, Suite 550 17 Chicago, Illinois 60612 18 Phone: 312-942-6100 19 Email: [email protected] 20 21 22 Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, laryngectomy 23 Sponsor or Funding Source: None 24 Conflicts of Interest: None 25 26 Author Contributions: 27 T.R.P.: Conception and design; data acquisition; drafting, revision, final approval of article 28 J.E.T.: Conception and design; data acquisition; drafting, revision, final approval of article 29 B.A.T.: Conception and design; drafting, revision, final approval of article 30 P.C.R.: Conception and design; drafting, revision, final approval of article 31 32 This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2 33 Introduction 34 Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus, has been declared 35 a pandemic by the World Health Organization1. -

Microbiology Specimen Collection

Martin Health System Stuart, Florida Laboratory Services Microbiology Specimen Collection The recovery of pathogenic organisms responsible for an infectious process is dependent on proper collection and transportation of a specimen. An improperly collected or transported specimen may lead to failure to isolate the causative organism(s) of an infectious disease or may result in the recovery and subsequent treatment of contaminating organisms. Improper handling of specimens may also lead to accidental exposure to infectious material. GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR COLLECTION: 1. Follow universal precaution guidelines, treating all specimens as potentially hazardous. 2. Whenever possible, collect specimen before antibiotics are administered. 3. Collect the specimen from the actual site of infection, avoiding contamination from adjacent tissues or secretions. 4. Collect the specimen at optimal time i.e. Early morning sputum for AFB First voided specimen for urine culture Specimens ordered x 3 should be 24 hours apart (exception: Blood cultures which are collected as indicated by the physician) 5. Collect sufficient quantity of material for tests requested. 6. Use appropriate collection and transport container. Refer to the Microbiology Quick Reference Chart or to the specific source guidelines. Containers should always be tightly sealed and leak-proof 7. Label the specimen with the Patient’s First and Last Name Date of Birth Collection Date and Time Collector’s First and Last Name Source 8. Submit specimen in the sealed portion of a Biohazard specimen bag. 9. Place signed laboratory order in the outside pocket of the specimen bag. 10. Include any pertinent information i.e. recent travel or relocation, previous antibiotic therapy, unusual suspected organisms, method or environment of wound infliction 11. -

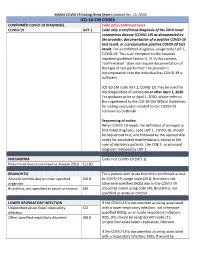

Icd-10-Cm Codes

MGMA COVID-19 Coding Cheat Sheet (Updated Dec. 23, 2020) ICD-10-CM CODES CONFIRMED COVID-19 DIAGNOSIS Code only confirmed cases COVID-19 U07.1 Code only a confirmed diagnosis of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) as documented by the provider, documentation of a positive COVID-19 test result, or a presumptive positive COVID-19 test result. For a confirmed diagnosis, assign code U07.1, COVID-19. This is an exception to the hospital inpatient guideline Section II, H. In this context, “confirmation” does not require documentation of the type of test performed; the provider’s documentation that the individual has COVID-19 is sufficient. ICD-10-CM code U07.1, COVID-19, may be used for discharges/date of service on or after April 1, 2020. For guidance prior to April 1, 2020, please refer to the supplement to the ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for coding encounters related to the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak. Sequencing of codes: When COVID-19 meets the definition of principal or first-listed diagnosis, code U07.1, COVID-19, should be sequenced first, and followed by the appropriate codes for associated manifestations, except in the case of obstetrics patients. Use O98.5- as principal diagnosis followed by U07.1. PNEUMONIA Code first COVID-19 (U07.1) Pneumonia due to coronavirus disease 2019 J12.82 BRONCHITIS For a patient with acute bronchitis confirmed as due Acute bronchitis due to other specified J20.8 to COVID-19, assign code J20.8. Bronchitis not organism otherwise specified (NOS) due to the COVID-19 Bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic J40 should be coded using code J40, Bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic. -

Respiratory Specimens

1.1. Department Of Pathology MIC.20650.04 Collection Guidelines - Respiratory Cultures Version#4 Department POLICY NO. PAGE NO. Microbiology 1408 1 OF 8 Printed copies are for reference only. Please refer to the electronic copy for the latest version. 1. Purpose 1.1. To provide accurate specimen collection information to the units as part of our on-line collection manual 2. Principles 2.1. Proper selection, collection, and handling of specimens for microbiology is necessary to ensure quality results that have the greatest impact on patient care. 3. Procedure The following page(s) have been posted on the on-line collection manual. • Note that much of the collection information was taken from the Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. The authors have written the following in their manual for collection procedures “the following can be coped for preparation of a specimen collection instruction manual for physicians and other caregivers” 4. References 4.1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards institute. 2008. Viral Culture; Approved Guideline; M41-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 4.2. York, Mary K, et al. (2004). Guidelines for Performance of Respiratory Tract. In Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook, Volume 2, (Isenberg, H. D., Ed.), pp. 3.11.1.1. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. 4.3. York, Mary K, et al. (2004). Lower Respiratory Tract Cultures. In Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook, Volume 2, (Isenberg, H. D., Ed.), pp. 3.11.2.1–10. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. 4.4. York, Mary K, et al. (2004). Body Fluid Cultures (Excluding Blood, Cerebral Spinal Fluid, and Urine). -

Influenza a (H5n1) Laboratory Information Bulletin

STATE OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Wadsworth Center The Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza P.O. Box 509 Albany, New York 12201-0509 Richard F. Daines, M.D. Commissioner October 30, 2007 INFLUENZA A (H5N1) LABORATORY INFORMATION BULLETIN This advisory is being sent to New York State permitted laboratories and Local Health Departments in response to requests for updated guidelines for the coming influenza season, particularly regarding H5N1 avian influenza. Please be advised that the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has issued separate guidance for the collection and referral of samples collected for Influenza A (H5N1) testing within New York City. In New York City, contact the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene through the Provider Access Line at 1-866-NYC-DOH1 (1-866-692-3641) during business hours. At all other times, call the Poison Control Center at 1-212-764-7667. BACKGROUND Since 2005, numerous outbreaks of H5N1 infection among poultry and wild birds have been confirmed in countries in Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. For a continually updated listing of affected countries, visit the World Health Organization of Animal Health (OIE) web site at: (http://www.oie.int/eng/en_index.htm) . Based on WHO data on October 8, 2007, since December 2003 a total of 330 cases, with 202 deaths, of H5N1 in humans have been confirmed worldwide. Updated human case listings can be obtained at the WHO web site: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/en/ H5N1 infections in humans can cause serious disease and death. -

Standard Guidelines for Medico-Legal Autopsy in Covid-19 Deaths in India 2020

STANDARD GUIDELINES FOR MEDICO-LEGAL AUTOPSY IN COVID-19 DEATHS IN INDIA 2020 New Delhi, India Page 1 of 30 ICMR, New Delhi Standard guidelines for Medico-legal autopsy in COVID-19 deaths in India 1st edition. © Indian Council of Medical Research 2019. All rights reserved Publications of the ICMR can be obtained from ICMR-HQ, Indian Council of Medical Research Division of ECD, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi, India Request for permission to reproduce or translate ICMR publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to ICMR-Hq at the above address. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the ICMR concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the ICMR in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions expected, the names of proprietary products aredistinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken bythe ICMR to verify the information contained in this publication. However, thepublished material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressedor implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with thereader. In no event shall ICMR be liable for damages arising from its use. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication. -

Preliminary Safety Recommendations in Rhinoplasty Post Covid-19

Preliminary Safety Recommendations in Rhinoplasty Post Covid-19 Rod J. Rohrich, M.D., F.A.C.S. Preliminary Safety Recommendations in Rhinoplasty Post Covid-19 Rod J. Rohrich, M.D., F.A.C.S. March 10‐ 11, 2021 March 12‐13, 2021 Global Covid These numbers of heavily dependent on presence of testing! Minimum Standard of Safe Practice at DPSI / DDSC • All office personnel and patients must wear masks/social distancing • Develop and follow office policies for screening and testing • Before any encounter, all patients must be screened for related Covid-19 symptoms or verify prior screening. • For care involving mucous membrane or respiratory tract (rhinoplasty), minimum PPE should include N95 mask or equivalent, and face shield. Minimum Standard of Safe Practice at DPSI / DDSC • UNIFORM STRICT PROTOCOLS TO BE FOLLOWED BY ALL • NO WAITING ROOMS/ NO REFRESHMENTS • NO MAGAZINES /NO COFFEE/NO TOUCH MATERIAL • PATIENTS WAIT for TEXT IN CAR -SLOWER PATIENT PACE • ALL ROOMS CLEANSED/DISINFECTED AFTER EACH PATIENT • ALL PUBLIC AREAS/ELEVATORS DISINFECTED EVERY HOUR Texas Society of Plastic Surgeon Recommendations • Screen patients and staff • Script staff with proper screening questionnaire • Identify high-risk patients • Clinic / Operating Room / UNIFORM STRICT Protocols Screening Patients and Staff Daily Staff Screening • Symptoms questionnaire • Temperature T>99.6 • Febrile, symptomatic HOME • Clean all personal phones when entering • Wash hands upon entering/leaving Screening Patients and Staff Daily Patient Screening • Symptoms questionnaire • -

Sinus and Anterior Skull Base Surgery During the COVID-19 Pandemic

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.01.20087304; this version posted May 6, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title page Manuscript title: Sinus and Anterior Skull Base Surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review, Synthesis and YO-IFOS position. Running Title: Sinus Surgery during COVID-19 pandemic Type of article: Systematic review Authors: Thomas Radulesco1,2,3, Jerome R. Lechien1,4,5, Leigh J Sowerby1,6, Sven Saussez1,4, Carlos Chiesa-Estomba1,7, Zoukaa Sargi1,8, Philippe Lavigne1,9, Christian Calvo- Henriquez1,10, Chwee Ming Lim1,11, Napadon Tangjaturonrasme1,12, Patravoot Vatanasapt1,13, Dehgani-Mobaraki Puya1,14,15, Nicolas Fakhry1,2, Tareck Ayad1,9, Justin Michel1,2,3. Affiliations 1 COVID-19 Task Force of the Young-Otolaryngologists of the International Federations of Oto-rhino- laryngological Societies (YO-IFOS). 2 APHM, Department of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, La Conception University Hospital, 13385 Marseille Cedex, France 3 Aix-Marseille University, IUSTI, 13013 Marseille, France 4 Department of Human Anatomy and Experimental Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, UMONS Research Institute for Health Sciences and Technology, University of Mons (UMons), Mons, Belgium 5 Department of Surgery, Foch Hospital, School of Medicine, UFR Simone Veil, Université Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (Paris Saclay University), Paris, France. 6 Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada. 7 Department of Otorhinolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery, Hospital Universitario Donostia, San Sebastian, Spain. -

Cobas SARS-Cov-2 Instructions For

Rx Only ® cobas SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay for use on the cobas® 6800/8800 Systems For use under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) only For in vitro diagnostic use cobas® SARS-CoV-2 - 192T P/N: 09175431190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 - 480T P/N: 09343733190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Control Kit P/N: 09175440190 cobas® 6800/8800 Buffer Negative Control Kit P/N: 07002238190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Table of contents Intended use ............................................................................................................................ 5 Summary and explanation of the test ................................................................................. 5 Reagents and materials ......................................................................................................... 7 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 reagents and controls ............................................................................................. 7 cobas omni reagents for sample preparation .......................................................................................... 9 Reagent storage and handling requirements ......................................................................................... 10 Additional materials required ................................................................................................................. 11 Instrumentation and software required ................................................................................................. 12 Precautions and handling requirements ........................................................................