Pathogenesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unusual Case of Non-Resolving Necrotizing Pneumonia: a Last Resort Measure for Cure

eCommons@AKU Department of Surgery Department of Surgery June 2016 Unusual case of non-resolving necrotizing pneumonia: a last resort measure for cure. Naseem Salahuddin Aga Khan University, [email protected] Naila Baig Ansari Aga Khan University Saulat H. Fatimi Aga Khan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_surg_surg Part of the Surgery Commons Recommended Citation Salahuddin, N., Ansari, N., Fatimi, S. (2016). Unusual case of non-resolving necrotizing pneumonia: a last resort measure for cure.. JPMA: Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 66(6), 754-756. Available at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_surg_surg/566 754 CASE REPORT Unusual case of non-resolving necrotizing pneumonia: A last resort measure for cure Naseem Salahuddin, 1 Naila Baig-Ansari, 2 Saulat Hasnain Fatimi 3 Abstract pathogen of acute CAP, 2,3 and accounts for most cases of To our knowledge, this is an unusual case of a community- slowly resolving pneumonia.The majority of previously acquired pneumonia (CAP) with sepsis secondary to healthy hospitalized patients with severe CAP responded Streptococcus pneumoniae that required lung resection satisfactorily to prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotic for a non-resolving consolidation. A 74 year old previously therapy; however, it is estimated that 10% of hospitalized healthy woman, presented with acute fever, chills and CAP patients have slowly resolving or nonresolving pleuritic chest pain in Emergency Department (ED). A disease. 4 diagnosis of CAP was established with a Pneumonia Severity Index CURB-65 score of 5/5. In the ER, she was Case Report promptly and appropriately managed with antibiotics History: A 74 year old woman who was previously and aggressive supportive therapy. -

COVID-19 and Neonatal Respiratory Care: Current Evidence and Practical Approach

Published online: 2020-05-02 780 Review Article COVID-19 and Neonatal Respiratory Care: Current Evidence and Practical Approach Wissam Shalish, MD1 Satyanarayana Lakshminrusimha, MD2 Paolo Manzoni, MD3 Martin Keszler, MD4 Guilherme M. Sant’Anna, MD, PhD, FRCPC1 1 Neonatal Division, Department of Pediatrics, McGill University Address for correspondence Guilherme M. Sant’Anna, MD, PhD, Health Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada FRCPC, Neonatal Division, Department of Pediatrics, McGill University 2 Department of Pediatrics, UC Davis, Sacramento, California Health Center, 1001 Décarie Boulevard, Room 05.2711, 3 Department of Pediatrics and Neonatology, University Hospital Montreal H4A 3J1, Canada (e-mail: [email protected]). Degli Infermi, Biella, Italy 4 Department of Pediatrics, Women and Infants Hospital, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island Am J Perinatol 2020;37:780–791. Abstract The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has urged the development and implementation of guidelines and protocols on diagnosis, management, infection control strategies, and discharge planning. However, very little is currently known about neonatal COVID-19 and severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections. Thus, many questions arise with regard to respiratory care after birth, necessary protection to health care workers (HCW) in the delivery room and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and safety of bag and mask ventilation, noninvasive respiratory support, deep suctioning, endotracheal intubation, and mechanical ventilation. Indeed, these questions have created tremendous confusion amongst neonatal HCW. In this manuscript, we comprehensively reviewed the current evidence regarding COVID-19 perinatal transmission, respiratory outcomes of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 and infants with documented SARS- CoV-2 infection, and the evidence for using different respiratory support modalities and aerosol-generating procedures in this specific population. -

Toman's Tuberculosis Case Detection, Treatment, and Monitoring

TOMAN’S TUBERCULOSIS TOMAN’S TUBERCULOSIS CASE DETECTION, TREATMENT, AND MONITORING The second edition of this practical, authoritative reference book provides a rational basis for the diagnosis and management of tuberculosis. Written by a number of experts in the field, it remains faithful to Kurt Toman’s original question-and-answer format, with subject matter grouped under the three headings Case detection, Treatment, and Monitoring. It is a testament to the enduring nature of the first edition that so much CASE DETECTION, TREA material has been retained unchanged. At the same time, the new edition has had not only to address the huge resurgence of tuber- culosis, the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacilli, and the special needs of HIV-infected individuals with tuberculosis, but also to encompass significant scientific advances. These changes in the profile of the disease and in approaches to management have inevitably prompted many new questions and answers and given a different complexion to others. Toman’s Tuberculosis remains essential reading for all who need to AND MONITORING TMENT, QUESTIONS learn more about every aspect of tuberculosis – case-finding, manage- ment, and effective control strategies. It provides invaluable support AND to anyone in the front line of the battle against this disease, from ANSWERS programme managers to policy-makers and from medical personnel to volunteer health workers. SECOND EDITION ISBN 92 4 154603 4 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION WHO GENEVA Toman’s Tuberculosis Case detection, treatment, and monitoring – questions and answers SECOND EDITION Edited by T. Frieden WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA 2004 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Toman’s tuberculosis case detection, treatment, and monitoring : questions and answers / edited by T. -

COVID-19 and Total Laryngectomy—A Report of Two Cases

AORXXX10.1177/0003489420935500Annals of Otology, Rhinology & LaryngologyPaderno et al 935500case-report2020 Case Report Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 1 –4 COVID-19 and Total Laryngectomy © The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions —A Report of Two Cases DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489420935500 10.1177/0003489420935500 journals.sagepub.com/home/aor Alberto Paderno, MD1 , Milena Fior, MD1, Giulia Berretti, MD1, Francesca Del Bon, MD1, Alberto Schreiber, MD, PhD1, Alberto Grammatica, MD1, Davide Mattavelli, MD1, and Alberto Deganello, MD, PhD1 Abstract Objective: To date, no cases have been reported on the effects of COVID-19 in laryngectomees. Case Presentation: We herein presented two clinical cases of laryngectomized patients affected by COVID-19, detailing their clinical course and complications. Discussion: In our experience, permanent tracheostomy did not significantly affect the choice of treatment. However, dedicated devices and repeated tracheal toilettes may be needed to deal with oxygen-therapy-related tracheal crusting. Conclusion: In conclusion, laryngectomees should be considered a vulnerable population that may be at risk for worse outcomes of COVID-19 due to anatomical changes in their airways. The role of the ENT specialist is to guide airway management and inform the support-staff regarding specific needs of these patients. Keywords COVID-19, coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, laryngectomy, management Introduction At admission (March 9, 2020), the most relevant clinical findings included severe oxygen desaturation (76%), tachy- To date, the effects of COVID-19 on laryngectomized pnea, cyanosis, lymphocytopenia, and C reactive protein patients is unknown, with no cases reported so far. After (CRP; 185 mg/L). -

Translational Deep Phenotyping of Deaths Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Protocol for a Prospective Observational Autopsy Study

Open access Protocol BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049083 on 27 August 2021. Downloaded from Translational deep phenotyping of deaths related to the COVID-19 pandemic: protocol for a prospective observational autopsy study Mikkel Jon Henningsen ,1 Apameh Khatam- Lashgari,1 Kristine Boisen Olsen,1 Christina Jacobsen,1 Christian Beltoft Brøchner ,2 Jytte Banner1 To cite: Henningsen MJ, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Khatam- Lashgari A, Olsen KB, Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic is an international et al. Translational deep emergency with an extreme socioeconomic impact and a ► A standardised, prospective autopsy study on COVID- phenotyping of deaths high mortality and disease burden. The COVID-19 outbreak related to the COVID-19 19- related deaths with systematic data collection. is neither fully understood nor fully pictured. Autopsy studies pandemic: protocol for a ► A multidisciplinary, translational approach elucidat- can help understand the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and has prospective observational ing changes from protein level to whole human. already resulted in better treatment of patients. Structured autopsy study. BMJ Open ► A comprehensive biobank and extensive registry and systematic autopsy of COVID-19- related deaths will 2021;11:e049083. doi:10.1136/ data as an umbrella for planned and future research. bmjopen-2021-049083 enhance the mapping of pathophysiological pathways, not ► The internal control group partly compensates for possible in the living. Furthermore, it provides an opportunity Prepublication history and the observational design. ► to envision factors translationally for the purpose of disease additional supplemental material ► Limited by a selected sample of COVID-19 diseased prevention in this and future pandemics. -

Treatment and Outcomes of Community-Acquired Pneumonia at Canadian Hospitals Research Brian G

Treatment and outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia at Canadian hospitals Research Brian G. Feagan,* Thomas J. Marrie,† Catherine Y. Lau,‡ Recherche Susan L. Wheeler,‡ Cindy J. Wong,* Margaret K. Vandervoort* From *the London Clinical Abstract Trials Research Group, London, Ont.; †the Background: Community-acquired pneumonia is a common disease with a large Department of Medicine, economic burden. We assessed clinical practices and outcomes among patients University of Alberta, with community-acquired pneumonia admitted to Canadian hospitals. Edmonton, Alta.; Methods: A total of 20 hospitals (11 teaching and 9 community) participated. Data and ‡Janssen–Ortho from the charts of adults admitted during November 1996, January 1997 and Incorporated, Toronto, Ont. March 1997 were reviewed to determine length of stay (LOS), admission to an intensive care unit and 30-day in-hospital mortality. Multivariate analyses exam- This article has been peer reviewed. ined sources of variability in LOS. The type and duration of antibiotic therapy and the proportion of patients who were treated according to clinical practice CMAJ 2000;162(10):1415-20 guidelines were determined. Results: A total of 858 eligible patients were identified; their mean age was 69.4 (standard deviation 17.7) years. The overall median LOS was 7.0 days (in- terquartile range [IQR] 4.0–11.0 days); the median LOS ranged from 5.0 to 9.0 days across hospitals (IQR 6.0–7.8 days). Only 22% of the variability in LOS could be explained by known factors (disease severity 12%; presence of chronic obstructive lung disease or bacterial cause for the pneumonia 2%; hospital site 7%). -

Respiratory Tract Infections in the Tropics

9.1 CHAPTER 9 Respiratory Tract Infections in the Tropics Tim J.J. Inglis 9.1 INTRODUCTION Acute respiratory infections are the single most common infective cause of death worldwide. This is also the case in the tropics, where they are a major cause of death in children under five. Bacterial pneumonia is particularly common in children in the tropics, and is more often lethal. Pulmonary tuberculosis is the single most common fatal infection and is more prevalent in many parts of the tropics due to a combination of endemic HIV infection and widespread poverty. A lack of diagnostic tests, limited access to effective treatment and some traditional healing practices exacerbate the impact of respiratory infection in tropical communities. The rapid urbanisation of populations in the tropics has increased the risk of transmitting respiratory pathogens. A combination of poverty and overcrowding in the peri- urban zones of rapidly expanding tropical cities promotes the epidemic spread of acute respiratory infection. PART A. INFECTIONS OF THE LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACT 9.2 PNEUMONIA 9.2.1 Frequency Over four million people die from acute respiratory infection per annum, mostly in developing countries. There is considerable overlap between these respiratory deaths and deaths due to tuberculosis, the single commonest fatal infection. The frequency of acute respiratory infection differs with location due to host, pathogen and environmental factors. Detailed figures are difficult to find and often need to be interpreted carefully, even for tuberculosis where data collection is more consistent. But in urban settings the enormity of respiratory infection is clearly evident. Up to half the patients attending hospital outpatient departments in developing countries have an acute respiratory infection. -

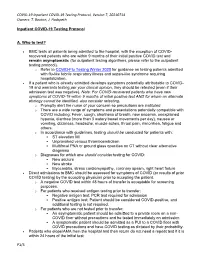

COVID 19 Inpatient Testing Guidelines

COVID-19 Inpatient COVID-19 Testing Protocol, Version 7, 20210714 Owners: T. Bouton, J. Hudspeth Inpatient COVID-19 Testing Protocol A. Who to test? BMC tests all patients being admitted to the hospital, with the exception of COVID- recovered patients who are within 9 months of their initial positive COVID test and remain asymptomatic (for outpatient testing algorithms, please refer to the outpatient testing protocol). o Refer to COVID-Flu Testing Winter 2020 for guidance on testing patients admitted with flu-like febrile respiratory illness and sepsis-like syndrome requiring hospitalization. If a patient who is already admitted develops symptoms potentially attributable to COVID- 19 and warrants testing per your clinical opinion, they should be retested (even if their admission test was negative). Note: For COVID-recovered patients who have new symptoms of COVID-19 within 9 months of initial positive test AND for whom an alternate etiology cannot be identified, also consider retesting. o Promptly alert the nurse of your concern so precautions are instituted o There are a wide range of symptoms and presentations potentially compatible with COVID including: Fever, cough, shortness of breath, new anosmia, unexplained hypoxia, diarrhea (more than 3 watery bowel movements per day), nausea or vomiting, dizziness, headache, muscle aches, throat pain, rhinorrhea, fatigue and others. o In accordance with guidelines, testing should be conducted for patients with: . ST elevation MI . Unprovoked venous thromboembolism . Multifocal PNA or ground glass opacities on CT without clear alternative diagnosis o Diagnoses for which one should consider testing for COVID: . New seizure . New stroke . Myocarditis, stress cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, right heart failure Direct admissions to BMC should be assessed for symptoms of COVID (or results of prior COVID testing) by the accepting physician prior to accepting the patient. -

Disparate Nasopharyngeal and Tracheal COVID-19 Diagnostic Test

Revised complete Manuscript Click here to access/download;Complete Manuscript;laryngectomy Testing manuscript plaintext.docx This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1 1 Disparate Nasopharyngeal and Tracheal COVID-19 Diagnostic Test 2 Results in a Patient with Total Laryngectomy 3 Running Title: “COVID-19 Testing with Total Laryngectomy” 4 5 Tirth R. Patel, MD1; Joshua E. Teitcher, CCC-SLP2; Bobby A. Tajudeen, MD1; Peter C. 6 Revenaugh, MD1 7 8 1. Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Rush University Medical 9 Center, Chicago, Illinois 10 2. Department of Hematology/Oncology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois 11 12 Corresponding Author: 13 Tirth R. Patel, MD 14 Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery 15 Rush University Medical Center 16 1650 West Harrison Street, Suite 550 17 Chicago, Illinois 60612 18 Phone: 312-942-6100 19 Email: [email protected] 20 21 22 Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, laryngectomy 23 Sponsor or Funding Source: None 24 Conflicts of Interest: None 25 26 Author Contributions: 27 T.R.P.: Conception and design; data acquisition; drafting, revision, final approval of article 28 J.E.T.: Conception and design; data acquisition; drafting, revision, final approval of article 29 B.A.T.: Conception and design; drafting, revision, final approval of article 30 P.C.R.: Conception and design; drafting, revision, final approval of article 31 32 This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2 33 Introduction 34 Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus, has been declared 35 a pandemic by the World Health Organization1. -

Microbiology Specimen Collection

Martin Health System Stuart, Florida Laboratory Services Microbiology Specimen Collection The recovery of pathogenic organisms responsible for an infectious process is dependent on proper collection and transportation of a specimen. An improperly collected or transported specimen may lead to failure to isolate the causative organism(s) of an infectious disease or may result in the recovery and subsequent treatment of contaminating organisms. Improper handling of specimens may also lead to accidental exposure to infectious material. GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR COLLECTION: 1. Follow universal precaution guidelines, treating all specimens as potentially hazardous. 2. Whenever possible, collect specimen before antibiotics are administered. 3. Collect the specimen from the actual site of infection, avoiding contamination from adjacent tissues or secretions. 4. Collect the specimen at optimal time i.e. Early morning sputum for AFB First voided specimen for urine culture Specimens ordered x 3 should be 24 hours apart (exception: Blood cultures which are collected as indicated by the physician) 5. Collect sufficient quantity of material for tests requested. 6. Use appropriate collection and transport container. Refer to the Microbiology Quick Reference Chart or to the specific source guidelines. Containers should always be tightly sealed and leak-proof 7. Label the specimen with the Patient’s First and Last Name Date of Birth Collection Date and Time Collector’s First and Last Name Source 8. Submit specimen in the sealed portion of a Biohazard specimen bag. 9. Place signed laboratory order in the outside pocket of the specimen bag. 10. Include any pertinent information i.e. recent travel or relocation, previous antibiotic therapy, unusual suspected organisms, method or environment of wound infliction 11. -

2017 Pulmonary Coding and Payment Quick Reference

2017 Coding & Payment Quick Reference Select Pulmonary Procedures Payer policies will vary and should be verified prior to treatment for limitations on diagnosis, coding or site of service requirements. The coding options listed within this guide are commonly used codes and are not intended to be an all-inclusive list. We recommend consulting your relevant manuals for appropriate coding options. Medicare Physician, Hospital Outpatient, and ASC Payments The bronchoscopy procedures listed below (except CPT® Codes 31622, 31660, and 31661) all include a diagnostic bronchoscopy when performed by the same physician. 2017 Medicare National Average Payment RVUs Physician‡,2 Facility3 CPT® Total Total Hospital Code Description Work In-Office In-Facility ASC Code1 Office Facility Outpatient Biopsy 31625 Bronchoscopy, rigid or flexible, including fluoroscopic guidance, 3.11 9.43 4.53 $338 $163 $1,270† $569 when performed; with bronchial or endobronchial biopsy(s), single or multiple sites 31628 Bronchoscopy, rigid or flexible, including fluoroscopic guidance, 3.55 10.00 5.09 $359 $183 $2,431† $1,117 when performed; with transbronchial lung biopsy(s), single lobe 31632 Bronchoscopy, rigid or flexible, including fluoroscopic guidance, 1.03 1.84 1.42 $66 $51 $0 $0 when performed; with transbronchial lung biopsy(s), each additional lobe (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure)* Cytology and Brush 31622 Bronchoscopy, rigid or flexible, including fluoroscopic guidance, 2.53 6.86 3.81 $246 $137 $1,270† $569 when performed; diagnostic, -

Community Acquired Pneumonia

Community Acquired Pneumonia MELISSA PALMER AGACNP Objectives Know the target population for the 2019 American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA) Community-acquired Pneumonia (CAP) guidelines 2019 Know when to perform testing for CAP: sputum cultures, blood cultures, Legionella and pneumococcal urinary antigen testing, influenza testing, and procalcitonin Be able to discuss the utilization of steroids in patients with CAP Know the selection of initial empiric antibiotic therapy for community-acquired pneumonia and duration of treatment for inpatients Criteria for hospitalization versus the need for ICU admission in adults diagnosed with CAP based on Pneumonia severity index (PSI) compared to CURB-65 Discuss the differences between the 2019 and 2007 ATS/IDSA Community-acquired Pneumonia Guidelines. COVID-19 Identify and Isolate. Pneumonia and CAP definition Pneumonia Infection of the alveoli, distal airways and the interstitium of the lung. Clinical: a new or changing radiographic density (infiltrate). Usually accompanied by constitutional symptoms of lung inflammation. Community Acquired Pneumonia acquired outside the hospital Signs and symptoms of pneumonia with radiographic confirmation *Patient must not have been hospitalized nor resided in a long-term-care facility for, at minimum, 14 days prior to the onset of symptoms Impact of Pneumonia leading infectious cause of hospitalization and death among U.S. adults more than 1.5 million adults hospitalized annually medical costs exceeding