Marine Protected Areas in Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba by Sea Cienfuegos to Havana Aboard Variety Voyager

MUSEUM TRAVEL ALLIANCE Cuba by Sea Cienfuegos to Havana Aboard Variety Voyager January 24–February 1, 2019 MUSEUM TRAVEL ALLIANCE Dear Members and Friends of the National Building Museum, Please join us next January for a cultural cruise along Cuba’s Caribbean coast. From Cienfuegos to Havana, we will journey aboard a privately chartered yacht, discovering well-preserved colonial architecture and fascinating small museums, visiting talented artists in their studios, and enjoying private concerts and other exclusive events. The Museum Travel Alliance (MTA) provides museums with the opportunity to offer their members and patrons high-end educational travel programming. Trips are available exclusively through MTA members and co-sponsoring non- profit institutions. This voyage is co-sponsored by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Association of Yale Alumni. Traveling with us on this cultural cruise are a Cuban-American architect and a partner in an award-winning design firm, a curator from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a Professor in the Music Department and African American Studies and American Studies at Yale University. In Cienfuegos, view the city’s French-accented buildings on an architectural tour before boarding the sleek Variety Voyager to travel to picturesque Trinidad. Admire the exquisite antiques and furniture displayed in the Romantic Museum and tour the studios of prominent local artists. Continue to Cayo Largo to meet local naturalists, and to remote Isla de la Juventud to see the Panopticon prison (now a museum) that once held Fidel Castro. We will also visit with marine ecologists on María la Gorda, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, before continuing to Havana for our two-day finale. -

Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Americas MRG Directory –> Cuba –> Cuba Overview Print Page Close Window Cuba Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment Cuba is the largest island in the Caribbean. It is located 150 kilometres south of the tip of the US state of Florida and east of the Yucatán Peninsula. On the east, Cuba is separated by the Windward Passage from Hispaniola, the island shared by Haiti and Dominican Republic. The total land area is 114,524 sq km, which includes the Isla de la Juventud (formerly called Isle of Pines) and other small adjacent islands. Peoples Main languages: Spanish Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant), syncretic African religions The majority of the population of Cuba is 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black and 1% Chinese (CIA, 2001). However, according to the Official 2002 Cuba Census, 65% of the population is white, 10% black and 25% mulatto. Although there are no distinct indigenous communities still in existence, some mixed but recognizably indigenous Ciboney-Taino-Arawak-descended populations are still considered to have survived in parts of rural Cuba. Furthermore the indigenous element is still in evidence, interwoven as part of the overall population's cultural and genetic heritage. There is no expatriate immigrant population. More than 75 per cent of the population is classified as urban. The revolutionary government, installed in 1959, has generally destroyed the rigid social stratification inherited from Spanish colonial rule. During Spanish colonial rule (and later under US influence) Cuba was a major sugar-producing territory. -

Haitian Migration and Danced Identity in Eastern Cuba

Haitian Migration and Danced Identity in Eastern Cuba The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Viddal, Grete. 2010. Haitian migration and danced identity in eastern Cuba. In Making Caribbean Dance: Continuity and Creativity in Island Cultures, ed. Susanna Sloat, 83-94. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. Published Version doi:10.5744/florida/9780813034676.003.0007 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10384888 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 7 Haitian Migration and Danced Identity in Eastern Cuba Grete Viddal I arrive at Santiago de Cuba’s Teatro Oriente to see a small crowd of locals and tourists waiting outside. We are here to see Ballet Folklórico Cutumba, one of eastern Cuba’s premier folkloric dance troupes. Although the theater is run down and no longer has electricity or running water, its former el- egance is apparent. As we enter, we see that lush but tattered velvet drapes flank the stage and ornate architectural details adorn the walls underneath faded and peeling paint. Light filters in through high windows. As the per- formance starts, women in elaborate ball gowns enter this dusty stage. They must hold up their voluminous skirts to keep yards of fabric from drag- ging on the floor. Men sport white topcoats with tails and matching white cravats. -

Categorización Preliminar De Taxones De La Flora De Cuba

Bissea, Vol. 7, Número Especial 2 Noviembre 2013 Versión impresa: ISSN 1998-4189 El Boletín sobre Conservación de Plantas del Jardín Botánico Nacional de Cuba Versión digital: ISSN 1998-4197 Categorización preliminar de taxones de la ora de Cuba - 2013 Editado por: Luis R. González-Torres Alejandro Palmarola Duniel Barrios Grupo de Especialistas en Plantas Cubanas (Comisión para la Supervivencia de las Especies/ Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza) Bissea es un boletín arbitrado, dedicado a difundir las acciones que se realizan por la conservación de la fl ora cubana. Bissea honra la memoria del Prof. Dr. Johannes Bisse, fundador del Jardín Botánico Nacional de Cuba, quien puso particular empeño en la formación de botánicos cubanos. Versión impresa: ISSN 1998-4189 Versión digital: ISSN 1998-4197 EDITORES: Luis R. González-Torres, Alejandro Palmarola y Duniel Barrios REVISIÓN: Grupo de Especialistas en Plantas Cubanas, CSE/UICN Consejo Científi co, Jardín Botánico Nacional, Univ. Habana Lisbet González, Eldis Bécquer & Ernesto Testé DISEÑO GRÁFICO: Alejandro Palmarola Categorización preliminar de DISEÑO EDITORIAL: Luis R. González-Torres © 2013, los autores. taxones de la ora de Cuba - © 2013, de la presente edición Jardín Botánico Nacional. La opinión de los autores no necesariamente refl eja la de los editores ni la del Jardín Botánico Nacional. La reproducción de cualquier parte de esta publicación con fi nes 2013 no comerciales está autorizada sin la solicitud de un permiso especial. Se agradece la citación de la fuente original. Bissea se distribuye gratuitamente en impreso y en electrónico. Para suscribirse o publicar dirija su correspondencia a [email protected] y [email protected]. -

I a Thesis Submitted to the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy of Central European University in Part Fulfilment O

A thesis submitted to the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy of Central European University in part fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Science An Ecological Coherence Assessment of the Wider Caribbean Region MPA Network CEU eTD Collection Rebecca GOTTLIEB June, 2021 Budapest i Erasmus Mundus Masters Course in Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management MESPOM This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the Master of Science degree awarded as a result of successful completion of the Erasmus Mundus Masters course in Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management (MESPOM) jointly operated by the University of the Aegean (Greece), Central European University (Hungary), Lund University (Sweden) and the University of Manchester (United Kingdom). CEU eTD Collection ii Notes on copyright and the ownership of intellectual property rights: (1) Copyright in text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the Author. (2) The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this thesis is vested in the Central European University, subject to any prior agreement to the contrary, and may not be made available for use by third parties without the written permission of the University, which will prescribe the terms and conditions of any such agreement. -

An Overview of Cuban Seagrasses

Bull Mar Sci. 94(2):269–282. 2018 research paper https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2017.1014 An overview of Cuban seagrasses Centro de Investigaciones Beatriz Martínez-Daranas * Marinas, Universidad de La Habana, Calle 16 No. 114, Ana M Suárez Miramar, Playa, Havana, 11300, Cuba. * Corresponding author email: <[email protected]>. ABSTRACT.—Here, we present an overview of the current knowledge of Cuban seagrasses, including distribution, status, threats, and efforts for their conservation. It has been estimated that seagrasses cover about 50% of the Cuban shelf, with six species reported and Thalassia testudinum K.D. Koenig being the most dominant. Seagrasses have been studied primarily in three areas in Cuba (northwest, north-central, and southwest). Thalassia testudinum and other seagrasses exhibit spatial and temporal variations in abundance, and updating of their status and distribution is needed. The main threat to Cuban seagrass ecosystems is low seawater transparency due to causes such as eutrophication and erosion. High salinities limit their distribution in the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago, partly the result of freshwater dams and roads. Seagrass meadows play important ecological k roles and provide many ecosystem services in Cuba, with efforts underway to preserve this ecosystem. Research and Marine Ecology and Conservation in Cuba management projects are directed toward integrated coastal zone management, including a ban on trawl fisheries and the Guest Editors: extension of marine protected areas to contain more seagrass Joe Roman, Patricia González-Díaz meadows. In addition to updating species distributions, it is Date Submitted: 17 February, 2017. urgent that managers and researchers in Cuba examine the Date Accepted: 22 November, 2017. -

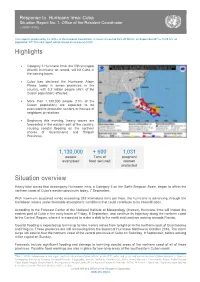

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

Page 12 El Pitirre 13(1) BARACOA Está Ubicado, Según La Clasificación

LISTADO PRELIMINAR DE LA AVIFAUNA DEL YUNQUE DE BARACOA, GUANTÁNAMO, CUBA 1 2 1 1 CARLOS PEÑA , NILS NAVARRO , ALEJANDRO FERNÁNDEZ Y SERGIO SIGARRETA VILCHES 1Departamento de Recursos Naturales, CITMA-Holguín, Cuba; y 2Grupo Proambiente, ENIA-Holguín, Cuba Resumen.—La región montañosa del Yunque de Baracoa al Este de Cuba tiene una elevación máxima de 1100 m y una pluviosidad anual de entre 1000-2000 mm. Esta es un área muy importante por su diversidad botánica y endemismo, pero además, es una región de interés dada su buena conservación. En años recientes, nosotros hemos llevado a cabo una evaluación de la avifauna de la región. Aquí presentamos una lista preliminar de las especies y de su categoría de distribución en la zona del Yunque de Baracoa, donde encontramos 68 espe- cies, representando 29 familias, e incluyendo 3 géneros endémicos y 8 especies endémicas Abstract.—PRELIMINARY LIST OF THE AVIFAUNA OF YUNQUE DE BARACOA, GUANTÁNAMO, CUBA. The moun- tainous region of Yunque de Baracoa of eastern Cuba has a maximum elevation of 1100 m and annual rain- fall of 1000-2000 mm. It is an important area of plant diversity and endemism, and thus is an area of conser- vation interest. In recent years we have undertaken the task of evaluating the region’s avifauna. Here we pre- sent a preliminary list of species and their status in the area of Yunque de Baracoa, where we found 68 spe- cies, representing 29 families, including 3 endemic genera and 8 endemic species. EL YUNQUE DE BARACOA está ubicado, según la “Cuchillas de Toa” (Alayón et al. -

Alexander Sánchez-Ruiz

ARTÍCULO: CURRENT TAXONOMIC STATUS OF THE FAMILY CAPONIIDAE (ARACHNIDA, ARANEAE) IN CUBA WITH THE DESCRIPTION OF TWO NEW SPECIES Alexander Sánchez-Ruiz Abstract: All information known about the spider species of the family Caponiidae recorded from Cuba is compiled. Two new species of the genus Nops MacLeay, 1839 (Araneae, Caponiidae) are described from eastern Cuba, raising to seven the number of species in the Caponiidae fauna of this archipelago. Key words: Araneae, Caponiidae, taxonomy, West Indies, Cuba. Taxonomy: Nops enae sp. n. Nops siboney sp. n. ARTÍCULO: Current taxonomic status of the Estado taxonómico actual de la familia Caponiidae (Arachnida, Araneae) en family Caponiidae (Arachnida, Cuba y descripción de dos especies nuevas Araneae) in Cuba with the description of two new species Resumen: Se recopila toda la información conocida acerca de las especies de arañas de la familia Alexander Sánchez-Ruiz Caponiidae registradas para Cuba. Se describen dos nuevas especies del género Nops Centro Oriental de Ecosistemas y MacLeay, 1839 (Araneae, Caponiidae) procedentes del oriente de Cuba, alcanzando las Biodiversidad, Museo de Historia siete especies la fauna de Caponiidae de este archipiélago. Natural “Tomás Romay”, José A. Palabras clave: Araneae, Caponiidae, taxonomía, Antillas, Cuba. Saco # 601, Santiago de Cuba Taxonomía: 90100, Cuba. Nops enae sp. n. [email protected] Nops siboney sp. n. Revista Ibérica de Aracnología ISSN: 1576 - 9518. Dep. Legal: Z-2656-2000. Introduction Vol. 9, 30-VI-2004 Sección: Artículos y Notas. The family Caponiidae in the New World is represented by nine genera: Calponia Pp: 95–102. Platnick 1993, Caponina Simon, 1891, Nops MacLeay, 1839, Nopsides Chamberlin, 1924, Notnops Platnick, 1994, Orthonops Chamberlin, 1924, Taintnops Platnick, Edita: 1994, Tarsonops Chamberlin, 1924 and Tisentnops Platnick, 1994. -

Introduced Amphibians and Reptiles in the Cuban Archipelago

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 10(3):985–1012. Submitted: 3 December 2014; Accepted: 14 October 2015; Published: 16 December 2015. INTRODUCED AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE CUBAN ARCHIPELAGO 1,5 2 3 RAFAEL BORROTO-PÁEZ , ROBERTO ALONSO BOSCH , BORIS A. FABRES , AND OSMANY 4 ALVAREZ GARCÍA 1Sociedad Cubana de Zoología, Carretera de Varona km 3.5, Boyeros, La Habana, Cuba 2Museo de Historia Natural ”Felipe Poey.” Facultad de Biología, Universidad de La Habana, La Habana, Cuba 3Environmental Protection in the Caribbean (EPIC), Green Cove Springs, Florida, USA 4Centro de Investigaciones de Mejoramiento Animal de la Ganadería Tropical, MINAGRI, Cotorro, La Habana, Cuba 5Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—The number of introductions and resulting established populations of amphibians and reptiles in Caribbean islands is alarming. Through an extensive review of information on Cuban herpetofauna, including protected area management plans, we present the first comprehensive inventory of introduced amphibians and reptiles in the Cuban archipelago. We classify species as Invasive, Established Non-invasive, Not Established, and Transported. We document the arrival of 26 species, five amphibians and 21 reptiles, in more than 35 different introduction events. Of the 26 species, we identify 11 species (42.3%), one amphibian and 10 reptiles, as established, with nine of them being invasive: Lithobates catesbeianus, Caiman crocodilus, Hemidactylus mabouia, H. angulatus, H. frenatus, Gonatodes albogularis, Sphaerodactylus argus, Gymnophthalmus underwoodi, and Indotyphlops braminus. We present the introduced range of each of the 26 species in the Cuban archipelago as well as the other Caribbean islands and document historical records, the population sources, dispersal pathways, introduction events, current status of distribution, and impacts. -

Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba

Stolen from the Archive of Dr. Antonio R. de la Cova http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/cuba-books.htm Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba Report to the President May 2004 Colin L. Powell Secretary of State Chairman Stolen from the Archive of Dr. Antonio R. de la Cova http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/cuba-books.htm FOREWORD by Secretary of State Colin L. Powell Over the past two decades, the Western Hemisphere has seen dramatic advances in the institutionalization of democracy and the spread of free market economies. Today, the nations of the Americas are working in close partnership to build a hemisphere based on political and economic freedom where dictators, traffickers and terrorists cannot thrive. As fate would have it, I was in Lima, Peru joining our hemispheric neighbors in the adoption of the Inter-American Democratic Charter when the terrorists struck the United States on September 11, 2001. By adopting the Democratic Charter, the countries of our hemisphere made a powerful statement in support of freedom, humanity and peace. Conspicuous for its absence on that historic occasion was Cuba. Cuba alone among the hemispheric nations did not adopt the Democratic Charter. That is not surprising, for Cuba alone among the nations of Americas is a dictatorship. For over four decades, the regime of Fidel Castro has imposed upon the Cuban people a communist system of government that systematically violates their most fundamental human rights. Just last year, the Castro regime consigned 75 human rights activists, independent librarians and journalists and democracy advocates to an average of nearly 20 years of imprisonment.