Middle Flight Ssm Journal of English Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

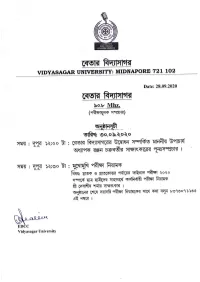

20200302 Vu Ce Gd Piii Cl

Office of the Controller of Examinations VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Midnapore - 721 102 Phone: 03222: 275-441/261-144/276-554-555 Extn.: 419/418/416/451/483/500/531 ............... Ref. No: VU/CE/GD/Partll/CL/2390/2020 Dated: March 02, 2020 Provisional List of centre for B.A. /B.Sc./ B.Com: Honours (Annual Pattern) Part: ~II Examination for the year 2020 .... NEW SYLLABUS . ' SI. Name of the Examination Centre Allotment to the Examination Centre No Colleges to appear No. of candidates Honours H.,~. B.Sc. B.Com Totai 01 Bajkul Milani Mahavidyalaya PK College 792 97 .108 997 Swarnamoyee J Mahavidyalaya YS Palpara Mahavidyalaya 02 Be Ida College Bhattar College, Narayangarh Govt. College, Govt. 391 01 02 394 Gen. Degree College, Dantan 11 03 Bhattar College Belda College 343 43 05 391 04 D<!bra Thana SKS Mahavidyalaya Sabang SK Mahavidyalaya, Siddhinath 343 15 12 370 Mahavidyalaya - 05 Egra SSB College Govt. Gen. Degree College, Mohanpur Ramnagar 301 16 51 368 College 06 Garhbeta College Chandrakona V Mahavidyalaya 523 20 0 543 Gourav Guin Memorial College Paramedical College, r;>urgapur SBSS Mahavidyalaya 07 RS Mahavidyalaya, Ghatal Chaipat SPBS Mahavidyalaya 472 19 0 491 Sukumar Sengupta Mahavidyalaya 08 l·laldia Govt. College Mahishadal Raj College 393 53 45 491 11 ;' 11111111 CJ" ciating) Controller Page ... 1 (Officiating) Vidyasagar University Midnapore-721102, W .B. Downloaded from Vidyasagar University; Copyright (c) Vidyasagar University http://ecircular.vidyasagar.ac.in/DownloadEcircular.aspx?RefId=202003027692 Office of the Controller of Examinations VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Midnapore - 721 102 Phone: 03222: 275-441/261-144/276-554-555 Extn.: 419/418/416/451/483/500/531 .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Unit 34 the Indian Xnglish Novel

UNIT 34 THE INDIAN XNGLISH NOVEL Structure Objectives Introduction Early lndian Writers in English Three Significant Novelists Post Independence Novelists Women Novelists Let Us Sum Up Answers to Self Check Exercises f 34.0 OBJECTIVES I This unit will deal with the lndian English novel. It will introduce you to the various phases of the development of the lndian English novel. To give you an overview of the development of the lndian English novel, we also give you a ' 'brief idea of the life and works of the major contributions to the development of this genre. By the end of the unit you will have a fair understanding of the phases in the development of the lndian English novel. 34.1 INTRODUCTION i 'The novel as a literary phenomenon is new to India. The novel came to life in I Rengal and then to other parts of India i.e. Madras and Bombay. Today lndian English novelists (whether living in India or abroad) are in the forefront I of New English Literatures worldwide. The names that immediately come to mind are Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth, Amitabh Ghosh, Arundhati Roy, Upamanyu Chatterjee, Amit Chaudhari and from the older lot Anita Desai and Nayantara Sehgal. I 34.2 EARLY INDIAN WRITERS IN ENGLISH Rajmohan's Wife (I 864) was the first and only English novel that Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1 838-94) wrote. 'Though Rajmohan 's Wife is not considered a very good novel, it established Bankim's place as the father of the novel in India. His novels Durgesh Nandini, Kapal Kundala, Vishmrik~ha, Krishana Kantar, Anandmath, Devi Chaudhrani along with others appeared between 1866 and 1886 and some of them appeared later in English versions. -

201804165520.Pdf

Office of the Controller ofExaminations VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Midnapore -721102 Phone: 03222: 275-4411261-144/276-554-555 Extn.: 419/418/416/4511483/500/531 ························································································································ Dated : April10, 2018 Schedule for Practical Examination for B.Sc. Honours Part-II Examination in Computer Science under old & new syllabus for Paper V- UNIT I I 50 for the year 2018 Exam Hours : 3 hours Time: 10a.m. to 1p.m./2p.m.- 5p.m. Date Paper & Colleges to appear & allotment of Students No. of Venue Set candidates 15.05.2018 V :U-1 Hijli College : all students : 02 17 Dept. of Computer Science Raja NLKWomens College: 21217139: 111-128 = 15 Debra Thana SKS Mahavidyalaya Set -I I 10-1 ... 17 College to be appeared : V: U-1 Raja NLKWomens College 21217139 129-148; 14 Hijli College Set -2 I 2-5 21216139: 68, 90 ... 14 Raja NLKWomens College 15.05.2018 V: U-1 P K College: 21217136: 110-140; 21216136: 119, 121, 17 Dept. of Computer Science 125,142 = 17 Hijli College Set -1 I 10-1 -- College to be appeared P K College 15.05.2018 V: U-1 Debra T SKS Mahavidyalaya 21217106 17-30; 18 Dept. of Computer Science 21216106:25,27,32,33,37 = 18 Panskura Banamali College Set -I I 10-1 College to be appeared : ) V: U-1 Chandrakona V Mahavidyalaya: 21216105: 03-10 = 05 21 Chandrakona V Mahavidyalaya Tamralipta Mahavidyalaya: 21217153 : 66-75; 21216153 Debra Thana SKS Mahavidyalaya Set -2 I 2-5 : 77,80,82 = 09 IV M Mahavidyalaya : 21217155 : 20- Tamralipta Mahavidyalaya 25; 21216155: 37-40 = 07 .. -

ENGLISH ELECTIVE Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA

ENGLISH ELECTIVE BA [English] Fourth Semester Paper G4 Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY Reviewer Deb Dulal Halder Assistant Professor, Kirori Mal College, Delhi University Authors Suchi Agrawal: Unit (1) © Suchi Agrawal, 2017 Prof Sanjeev Nandan Prasad: Unit (2.0-2.2) © Prof Sanjeev Nandan Prasad, 2017 Prateek Ranjan Jha: Units (2.3-2.4, 3, 4) © Reserved, 2017 Vikas Publishing House: Unit ( 2.5-2.10) © Reserved, 2017 Books are developed, printed and published on behalf of Directorate of Distance Education, Tripura University by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material, protected by this copyright notice may not be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form of by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the DDE, Tripura University & Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT. LTD. E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 • Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi 110 055 • Website: www.vikaspublishing.com • Email: [email protected] SYLLABI-BOOK MAPPING TABLE English Elective Syllabi Mapping in Book Unit I: Indian English Novel Unit 1: Indian English Novel: The R.K. -

SSR 2012 Vol.2

SABANG SAJANIKANTA MAHAVIDYALAYA P.O.- LUTUNIA * DIST.- PASCHIM MEDINIPUR (W.B.) PIN- 721166 * PHONE NO.- (03222) 248221 Ref. No. …………..... Date …............. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We are very much grateful and indebted to Dr. K. L. Paria, Principal, Sabang Sajanikanta Mahavidyalaya for his inspiring and tireless guidance and constant encouragement, throughout the period of the present work. We convey our sincere thanks to the members of the Governing Body of our college for giving us the chance of coordinating this job. We are grateful to Dr. B. S. Mukherjee, Associate Professor & Head of the Department of Sanskrit, Dr. T. Mishra, Assistant Professor, Department of Physics for preparation of this SSR. We are also thankful to office staff, Mr. Sukumar Patra and all other office staff for their kind cooperation at every stage of need. We acknowledge our deep sense of gratitude and indebtedness to General Secretary, Student Union of Sabang Sajanikanta Mahavidyalaya, for his valuable help at every step of this work. We are also thankful to all the members of teaching, non teaching, library and hostel staff for their help in the preparation of SSR of Sabang Sajanikanta Mahavidyalaya.. We are greatly indebted to our family, for their patience, understanding and encouragement, without which this work could not have been completed. Mr. Harekrishna Bar Mr. Sudhansu Samanta Joint Co-coordinator Co-coordinator NAAC Steering Committee NAAC Steering Committee Sabang Sajanikanta Mahavidyalaya Sabang Sajanikanta Mahavidyalaya SSR Vol.‐ II 2012 SABANG SAJANIKANTA MAHAVIDYALAYA SELF STUDY REPORT Volume II Submitted to NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL Bangalore-560072 Nov. 2012 Sabang Sajanikanta Mahavidyalaya Page 1 SSR Vol.‐ II 2012 Content 1. -

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-Aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt. No. 1/2018) Bengali UR OBC-A OBC-B SC ST PWD 43 13 1 30 25 6 Sl No College University UR 1 Bankura Zilla Saradamoni Mahila Mahavidyalaya 2 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya. 3 Panchmura Mahavidyalaya. BANKURA UNIVERSITY 4 Pandit Raghunath Murmu Smriti Mahavidyalaya.(1986) 5 Saltora Netaji Centenary College 6 Sonamukhi College 7 Hiralal Bhakat College 8 Kabi Joydeb Mahavidyalaya 9 Kandra Radhakanta Kundu Mahavidyalaya BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 10 Mankar College 11 Netaji Mahavidyalaya 12 New Alipore College CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 13 Balurghat Mahila Mahavidyalaya 14 Chanchal College 15 Gangarampur College 16 Harishchandrapur College GOUR BANGA UNIVERSITY 17 Kaliyaganj College 18 Malda College 19 Malda Women's College 20 Pakuahat Degree College 21 Jangipur College 22 Krishnath College 23 Lalgola College KALYANI UNIVERSITY 24 Sewnarayan Rameswar Fatepuria College 25 Srikrishna College 26 Michael Madhusudan Memorial College KAZI NAZRUL UNIVERSITY (ASANSOL) 27 Alipurduar College 28 Falakata College 29 Ghoshpukur College NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY 30 Siliguri College 31 Vivekananda College, Alipurduar 32 Mahatma Gandhi College SIDHO KANHO BIRSHA UNIVERSITY 33 Panchakot Mahavidyalaya 34 Bhatter College, Dantan 35 Bhatter College, Dantan 36 Debra Thana Sahid Kshudiram Smriti Mahavidyalaya VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 37 Hijli College 38 Mahishadal Raj College 39 Vivekananda Satavarshiki Mahavidyalaya 40 Dinabandhu -

Education General Sc St Obc(A) Obc(B) Ph/Vh Total Vacancy 37 44 19 16 17 4 137 General

EDUCATION GENERAL SC ST OBC(A) OBC(B) PH/VH TOTAL VACANCY 37 44 19 16 17 4 137 GENERAL Sl No. University College Total 1 RAJ NAGAR MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 2 SWAMI DHANANJAY DAS KATHIABABA MV, BHARA 1 3 AZAD HIND FOUZ SMRITI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 4 BARUIPUR COLLEGE 1 5 DHOLA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 6 HERAMBA CHANDRA COLLEGE 1 7 CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY MAHARAJA SRIS CHANDRA COLLEGE 1 8 SERAMPORE GIRLS' COLLEGE 1 9 SIBANI MANDAL MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 10 SONARPUR MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 11 SUNDARBAN HAZI DESARAT COLLEGE 1 12 GANGARAMPUR COLLEGE 1 13 GOURBANGA UNIVERSITY NATHANIEL MURMU COLLEGE 1 14 SOUTH MALDA COLLEGE 1 15 DUKHULAL NIBARAN CHANDRA COLLEGE 1 16 HAZI A. K. KHAN COLLEGE 1 17 KALYANI UNIVERSITY NUR MOHAMMAD SMRITI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 18 PLASSEY COLLEGE 1 19 SUBHAS CHADRA BOSE CENTENARY COLLEGE 1 20 CLUNY WOMENS COLLEGE 1 21 LILABATI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY 22 NAKSHALBARI COLLEGE 1 23 RAJGANJ MAHAVIDYALAYA, RAJGANJ 1 24 ARSHA COLLEGE 1 SIDHO KANHO BIRSA UNIVERSITY 25 KOTSHILA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 26 BHATTER COLLEGE 1 27 GOURAV GUIN MEMORIAL COLLEGE 1 28 PANSKURA BANAMALI COLLEGE 1 VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 29 RABINDRA BHARATI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 30 SIDDHINATH MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 31 SUKUMAR SENGUPTA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 32 BARRAKPORE RASHTRAGURU SURENDRANATH COLLEGE 1 33 KALINAGAR MV 1 34 MAHADEVANANDA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 WEST BENGAL STATE UNIVERSITY 35 NETAJI SATABARSHIKI MAHABIDYALAYA 1 36 P.N.DAS COLLEGE 1 37 RISHI BANKIM CHANDRA COLLEGE FOR WOMEN 1 OBC(A) 1 HOOGHLY WOMEN'S COLLEGE 1 BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 2 KABI JOYDEB MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 3 GANGADHARPUR MAHAVIDYALAYA -

870418Aintimation Information For

Mailbox of bajkul_college Subject: Intimation information for Transmission in Betar Vidyasagar From: Dr. Avijit Roychoudhury Inspector of Colleges <[email protected]> on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:49:01 To: General Degree College <[email protected]>, "Govt. General Degree College" <[email protected]>, Bajkul Milani Mahavidyalaya <[email protected]>, Belda College <[email protected]>, Bhatter College <[email protected]>, Chaipat Shahid Pradyot Bhattacharyya Mahavidyalaya <[email protected]>, Chandrakona Vidyasagar Mahavidyalaya <[email protected]>, Debra Thana Shahid Khudiram Smriti Mahavidyalaya <[email protected]>, Deshapran Mahavidyalaya <[email protected]>, Egra Sarada Sashi Bhusan Mahavidyalaya <[email protected]>, Garhbeta College <[email protected]>, GGDC Dantan-II <[email protected]>, GGDC Gopi -II <[email protected]>, GGDC Keshiary <[email protected]>, GGDC Kgp - II <[email protected]>, GGDC Mohanpur <[email protected]>, GGDC Narayangarh <[email protected]>, Gourav Guin Memorial College <[email protected]>, "Haldia Govt. College" <[email protected]>, Hijli College <[email protected]>, "Jhargram Raj Coll (Girls)" <[email protected]>, Jhargram Raj College <[email protected]>, "Kaibalyadayini College of Commerce & General Studies" <[email protected]>, Kharagpur College <[email protected]>, Khejuri College <[email protected]>, "Lalgarh -

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status for the Posts of Principal in Govt

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status for the Posts of Principal in Govt. – Aided General Degree Colleges (Advt. No. 2/2015) Sl. No. Name of the Colleges University 1 Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose College 2 Bankim Sardar College 3 Baruipur College 4 Behela College 5 Calcutta Girls’ College 6 Charuchandra College 7 Dr. Kanailal Bhattacharya College 8 Gurudas College 9 Harimohan Ghosh College 10 Jibantala College 11 Jogamaya Devi College 12 Kishore Bharati Bhagini Nivedita College 13 Narasingha Dutt College 14 Netaji Nagar College CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 15 New Alipur College 16 Panchla Mahavidyalaya 17 Pathar Pratima Mahavidyalaya 18 Prafulla Chandra College 19 Raja Peary Mohan College 20 Robin Mukherjee College 21 Sagar Mahavidyalaya 22 Sibani Mandal Mahavidyalaya 23 Sir Gurudas Mahavidyalaya 24 Shishuram Das College 25 South Calcutta Girls’ College 26 Sundarban Mahavidyalaya 27 Surendranath Law College 28 Vijaygarh Jyotish Ray College 29 Berhampore Girls’ College 30 Bethuadahari College 31 Chapra Bangali College 32 Domkal College (Basantapur) 33 Domkal Girls’ College 34 Dr. B. R. Ambedkar College 35 Dukhulal Nibaran Chandra College 36 Hazi A. K. Khan College 37 Jangipur College 38 Jatindra-Rajendra Mahavidyalaya 39 Kalyani Mahavidyalaya 40 Kandi Raj College 41 Karimpur Pannadevi College KALYANI UNIVERSITY 42 Lalgola College 43 Murshidabad Adarsha Mahavidyalaya 44 Muzaffar Ahmed Mahavidyalaya 45 Nabadwip Vidyasagar College 46 Nur Mohammed Smriti Mahavidyalaya 47 Plassey College 48 Raja Birendra Chandra College 49 Ranaghat College 50 Sagardighi Kamada Kinkar Smriti Mahavidyalaya 51 S. R. Fatepuria College 52 Subhas Chandra Bose Centenary College 53 Jalangi College 54 Nabagram Amarchand Kundu College Sl. No. Name of the Colleges University 55 Abhedananda Mahavidyalalya 56 Acharya Sukumar Sen Mahavidyalaya 57 Asansol Girls’ College 58 Banwarilal Bhalotia College, Assansol 59 Bidhan Chandra College Assansol 60 Birsa Munda Memorial College 61 Chatna Chandidas Mahavidyalaya 62 Chatra Ramai Pandit Mahavidyalaya 63 Dasarathi Hazra Memorial College 64 Dr. -

A Room of Their Own: Women Novelists 109

A Room of their Own: Women Novelists 109 4 A Room of their Own: Women Novelists There is a clear distinction between the fiction of the old masters and the new novel, with Rushdie's Midnight's Children providing a convenient watershed. When it comes to women novelists, the distinction is not so clear cut. The older generation of women writers (they are a generation younger than the "Big Three") have produced significant work in the nineteen-eighties: Anita Desai's and Nayantara Sahgal's best work appeared in this period. We also have the phenomenon of the "late bloomers": Shashi Deshpande (b. 1937) and Nisha da Cunha (b. 1940) have published their first novel and first collection of short stories in the eighties and nineties respectively. But the men and women writers also have much in common. Women too have written novels of Magic Realism, social realism and regional fiction, and benefited from the increasing attention (and money) that this fiction has received, there being an Arundhati Roy to compare with Vikram Seth in terms of royalties and media attention. In terms of numbers, less women writers have been published abroad; some of the best work has come from stay-at- home novelists like Shashi Deshpande. Older Novelists Kamala Markandaya has published just one novel after 1980. Pleasure City (1982) marks a new direction in her work. The cultural confrontation here is not the usual East verses West, it is tradition and modernity. An efficient multinational corporation comes to a sleepy fishing village on the Coromandal coast to built a holiday resort, Shalimar, the pleasure city; and the villagers, struggling at subsistence level, cannot resist the regular income offered by jobs in it. -

The Technique of Double Narration of R. K. Narayan's the Guide

International Journal of Language and Literature, Vol. 1 No. 2, December 2013 37 The Technique of Double Narration of R. K. Narayan’s The Guide V. S SANKARA RAO CHINNAM. M.A, B.Ed., M. Phil.1 Abstract R. K. Narayan is one of the three important Indian novelists in English. Mulk Raj Anand and Raja Rao are the other two important novelists. Narayan’s novels deal with the life of average middle class man is very important. He looks at common life with a sense of realist humour. He criticizes with gentle irony the middle class hypocrisy. He looks at life with a curious interest. He is detached observe of our ordinary interest. The Guide attempts at reviving the ethnic cultures, traditions, beliefs and languages. He writes about a cross- section of the Indian society. His characters are drawn from a wide variety of situations. They are not rich, they are also not poor. They came from the typical middle class situations. They are also resourceful. They have enough common sense; they are keen observers of life. Their qualities are unfailing, strenuous hard work. They have a teeming sense of life. They are always hopeful participants in life. They are all born optimists. Narayan has employed a double narrative techniques, he uses the narrative techniques with purpose. He uses flash-back narrative technique. This makes Raju estimate his own personality. In this narration of past life, Raju shows enough honesty and sincerity. He portrays himself with great boldness. The Guide is one of Narayan’s most interesting and popular works and is told in a series of flashbacks.