Surviving Congregational Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs in the Night Charles Spurgeon (1834 – 1892) English Baptist Preacher

SONGSCHARLES SPURGEON IN THE (1834 NIGHT – 1892) SONGS IN THE NIGHT CHARLES SPURGEON (1834 – 1892) ENGLISH BAPTIST PREACHER A sermon intended for reading on Lord’s-Day, February 27, 1898 (delivered at New Park Street Chapel, Southwark) But none says, Where is God my Maker, who gives songs in the night? (Job 35:10) lihu was a wise man, exceedingly wise, though not as wise as the all-wise Jehovah, who sees light in the clouds, and finds order in confusion; hence Elihu, being much puzzled at beholding Job so afflicted, cast about him to find the cause of it, and he very wisely hit upon one of the most likely reasons, although it did not happen to be E the right one in Job’s case. He said within himself, “Surely, if men are sorely tried and troubled, it is because, while they think about their troubles, and distress themselves about their fears, they do not say, ‘Where is God my Maker, who gives songs in the night?’” Elihu’s reason is right in the majority of cases. The great cause of a Christian’s distress, the reason of the depths of sorrow into which many believers are plunged, is simply this — that while they are looking about, on the right hand and on the left, to see how they may escape their troubles, they forget to look to the hills from where all real help comes; they do not say, “Where is God my Maker, who gives songs in the night?” We shall, however, leave that inquiry, and dwell upon those sweet words, “God my Maker, who gives songs in the night.” The world has its night. -

The Metropolitan Sabernacle

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com TheMetropolitansabernacle;itshistoryandwork C.H.Spurgeon ' 4. THE ITS HISTORY AND WORK. BY C. H. SPURGEON. Hontion : PASSMORE & ALABASTER, PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS. PREFACE. When modest ministers submit their sermons to the press they usually place upon the title page the words " Printed iy Request." We might with emphatic truthfulness have pleaded this apology for the present narrative, for times without number friends from all parts of the world have said, " Have you no book which will tell us all about your work ? Could you not give us some printed summary of the Tabernacle history ? " Here it is, dear friends, and we hope it will satisfy your curiosity and deepen your kindly interest. The best excuse for writing a history is that there is something to tell, and unless we are greatly mistaken the facts here placed on record are well worthy of being known. In us they have aroused fervent emotions of gratitude, and in putting them together our faith in God has been greatly established: we hope, therefore, that in some measure our readers will derive the same benefit. Strangers cannot be expected to feel an equal interest with ourselves, but our fellow members, our co-workers, our hundreds of generous helpers, and the large circle of our hearty sympathizers cannot read our summary of the Lord's dealings with us without stimulus and encouragement. Our young people ought to be told by their fathers the wondrous things which God did in their day " and in the old time before them." Such things are forgotten if they are not every now and then rehearsed anew in the ears of fresh generations. -

Baptists in America LIVE Streaming Many Baptists Have Preferred to Be Baptized in “Living Waters” Flowing in a River Or Stream On/ El S

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 126 Baptists in America Did you know? you Did AND CLI FOUNDING SCHOOLS,JOININGTHEAR Baptists “churchingthe MB “se-Baptist” (self-Baptist). “There is good warrant for (self-Baptist). “se-Baptist” manyfession Their shortened but of that Faith,” to described his group as “Christians Baptized on Pro so baptized he himself Smyth and his in followers 1609. dam convinced him baptism, the of need believer’s for established Anglican Mennonites Church). in Amster wanted(“Separatists” be to independent England’s of can became priest, aSeparatist in pastor Holland BaptistEarly founder John Smyth, originally an Angli SELF-SERVE BAPTISM ING TREES M selves,” M Y, - - - followers eventuallyfollowers did join the Mennonite Church. him as aMennonite. They refused, though his some of issue and asked the local Mennonite church baptize to rethought later He baptism the themselves.” put upon two men singly“For are church; no two so may men a manchurching himself,” Smyth wrote his about act. would later later would cated because his of Baptist beliefs. Ironically Brown Dunster had been fired and in his 1654 house confis In fact HarvardLeague Henry president College today. nial schools,which mostof are members the of Ivy Baptists often were barred from attending other colo Baptist oldest college1764—the in the United States. helped graduates found to Its Brown University in still it exists Bristol, England,founded at in today. 1679; The first Baptist college, Bristol Baptist was College, IVY-COVERED WALLSOFSEPARATION LIVE “E discharged -

Colombia: 1629-1996

A CHRONOLOGY OF PROTESTANT BEGINNINGS IN COLOMBIA: 1629-1996 By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES (Last revised on 15 October 2009) Historical Overview of Colombia: Spain conquered northern South America, later called New Granada: 1536-1539 First Roman Catholic diocese established: 1534 Independence from Spain declared: 1819 Gen. Simón Bolivar liberated New Granada (included the modern countries of Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador) from Spain: 1819 The Federation of Gran Colombia formed: 1822 Ecuador and Venezuela become independent republics: 1829-1830 Republic of New Granada (included the Province of Panamá) established: 1830 New Granada renamed Colombia: 1863 Religious Liberty granted: 1886 Concordats with Rome established: 1887, 1974 War of a Thousand Days fought: 1899-1901 Republic of Panama becomes independent of Colombia: 1903 Religious/civil war La Violencia : 1948-1958 Number of North American Protestant Mission Agencies in 1989: 92 Number of North American Protestant Mission Agencies in 1996: 70 Indicates European Mission Society or Service Agency * Significant Protestant Beginnings: 1629 - *Puritan colonists settle on San Andrés and Providencia islands (Caribbean Sea) under British rule until 1783 (Treaty of Versailles), when the islands reverted to Spanish control. 1824 - *British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) colporteur James Thomson established a short-lived Colombian Bible Society. 1837 - *BFBS office established in Cartagena (1837-1838). 1844 – Baptists from the U.S. Southern states arrive in San Andrés-Providencia islands and establish Baptist churches among the Creole population. 1853 - *Two Swiss evangelicals visited Bogotá, taught Bible studies and distributed New Testaments. 1855 - The Rev. Ramón Montsalvatge began evangelical work in Cartagena (1855- 1867). 1856 - *BFBS agency was established in Bogotá, A. -

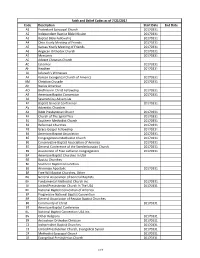

Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church

Faith and Belief Codes as of 7/21/2017 Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church 20170331 A2 Independent Baptist Bible Mission 20170331 A3 Baptist Bible Fellowship 20170331 A4 Ohio Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A5 Kansas Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A6 Anglican Orthodox Church 20170331 A7 Messianic 20170331 AC Advent Christian Church AD Eckankar 20170331 AH Heathen 20170331 AJ Jehovah’s Witnesses AK Korean Evangelical Church of America 20170331 AM Christian Crusade 20170331 AN Native American AO Brethren In Christ Fellowship 20170331 AR American Baptist Convention 20170331 AS Seventh Day Adventists AT Baptist General Conference 20170331 AV Adventist Churches AX Bible Presbyterian Church 20170331 AY Church of The Spiral Tree 20170331 B1 Southern Methodist Church 20170331 B2 Reformed Churches 20170331 B3 Grace Gospel Fellowship 20170331 B4 American Baptist Association 20170331 B5 Congregational Methodist Church 20170331 B6 Conservative Baptist Association of America 20170331 B7 General Conference of the Swedenborgian Church 20170331 B9 Association of Free Lutheran Congregations 20170331 BA American Baptist Churches In USA BB Baptist Churches BC Southern Baptist Convention BE Armenian Apostolic 20170331 BF Free Will Baptist Churches, Other BG General Association of General Baptists BH Fundamental Methodist Church Inc. 20170331 BI United Presbyterian Church In The USA 20170331 BN National Baptist Convention of America BP Progressive National Baptist Convention BR General Association of Regular Baptist -

Highlights in Life of CH Spurgeon

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY COLLECTIONS HIGHLIGHTS IN THE LIFE OF CHARLES HADDON SPURGEON by Eric W. Hayden To the Students of the Words, Works and Ways of God: Welcome to the AGES Digital Library. We trust your experience with this and other volumes in the Library fulfills our motto and vision which is our commitment to you: MAKING THE WORDS OF THE WISE AVAILABLE TO ALL — INEXPENSIVELY. AGES Software Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1 — The 1834-55 The Formative Years Chapter 2 — 1855 “Catchem Alive-O” Chapter 3 — 1856 Controversy and Confession Chapter 4 — 1857 The Wider Ministry Chapter 5 — 1858 The American Interest Chapter 6 — 1859 The Tabernacle Stone-laying Chapter 7 — 1860 Raising Funds Chapter 8 — 1861 The Tabernacle Opened Chapter 9 — 1862 The Pastor’s College Chapter 10 — 1863 The Sermons Translated Chapter 11 — 864 Tenth Anniversary Chapter 12 — 1865 Thirty Years of Age Chapter 13 — 1865 Battling and Building Chapter 14 — 1866 Three New Institutions Chapter 15 — 1867 The Tabernacle Renovated Chapter 16 — 1868 Protestants Encouraged Chapter 17 — 1869 Thirty-Five Years of Age Chapter 18 — 1870 Sermon Sales Chapter 19 — 1871 Preaching in Rome Chapter 20 — 1872 An Attempt at Church Unity Chapter 21 — 1873 The New College Building Chapter 22 — 1874 Forty Years of Age Chapter 23 — 1875 D. L. Moody at the Tabernacle 3 Chapter 24 — 1876 Mrs. C. H. Spurgeon’s Book Fund Chapter 25 — 1877 “Open Day” at the Orphanage Chapter 26 — 1878 Testimonial Year Chapter 27 — 1879 Silver Wedding Testimonial Chapter 28 — 1880 “Sermon -

Lowship International * Independent Baptist Fellowship of North America

Alliance of Baptists * American Baptist Association * American Baptist Churches USA * Association of Baptist Churches in Ireland * Association of Grace Baptist Churches * Association of Reformed Baptist Churches of America * Association of Regular Baptist Churches * Baptist Bible Fellowship International * Baptist Conference of the Philippines * Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec * Baptist Convention of Western Cuba * Baptist General Conference (formally Swedish Baptist General Conference) * Baptist General Conference of Canada * Baptist General Convention of Texas * Baptist Missionary Association of America * Baptist Union of Australia * Baptist Union of Great Britain * Baptist Union of New Zealand * Baptist Union of Scotland * Baptist Union of Western Can- ada * Baptist World Alliance * Bible Baptist * Canadian Baptist Ministries * Canadian Convention of Southern Baptists * Cen- tral Baptist Association * Central Canada Baptist Conference * Christian Unity Baptist Association * COLORED PRIMITIVE BAPTISTS * Conservative Baptist Association * Conservative Baptist Association of America * Conservative Baptists * Continental Baptist Churches * Convención Nacional Bautista de Mexico * Convention of Atlantic Baptist Churches * Coop- erative Baptist Fellowship * Crosspoint Chinese Church of Silicon Valley * European Baptist Convention * European Bap- tist Federation * Evangelical Baptist Mission of South Haiti * Evangelical Free Baptist Church * Fellowship of Evan- gelical Baptist Churches in Canada * Free Will Baptist Church * Fun- damental -

A Chronology of Protestant Beginnings: Brazil

A CHRONOLOGY OF PROTESTANT BEGINNINGS: BRAZIL By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES (Last revised on 31 October 2017) Brief Historical Overview of Brazil: Discovered by Spanish explorer Vicente Yanez Pinzón but Spain made no claim to this 26 January territory. 1500 Discovered by Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares de Cabral who claimed the territory for the 24 April 1500 King of Portugal. Became Portuguese Colony 1511 Period of Brazilian Monarchy: son of Portuguese king declares independence from Portugal 1822-1889 and crowns himself Peter I, Emperor of Brazil. Monarchy overthrown, federal republic established with central government controlled by 1889 coffee interests. Religious Liberty established. 1891 Number of North American mission agencies in 1989 165 Number of North American mission agencies in 1996 124 Number of North American mission agencies in 2006 152 Indicates European missionary society* Significant Protestant Beginnings: Pre-1900 Period 1555-1566 - *French Huguenot colony (Calvinists) established under French commander Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon; the first Protestant worship service was held in Brazil on 10 March 1557; the French were expelled by the Portuguese in 1566. 1624-1654 - *Dutch colony (Calvinists) and mission efforts on Northeast coast at Recife; the Dutch were expelled by the Portuguese in 1654. 1816 - *First Anglican chaplain arrived in Brazil at Rio de Janeiro; Robert C. Crane. 1817 - *British and Foreign Bible Society colporteurs 1822 - *First Anglican chapel was dedicated on 26 May in Rio de Janeiro to serve the expatriate community of mostly British citizens. 1824 - First German Lutheran immigrants arrived in the Southern Region at São Leopoldo, Rio Grande do Sul, and Blumenan, Santa Catarina; first Lutheran Church was established at Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro. -

The Process Begins When an Applicant Enters a Recruiters Office and Expresses Interest in Joining the Air Force

The process begins when an applicant enters a recruiters office and expresses interest in joining the Air Force. To get started the recruiter asks the applicant to complete the SF-86 "Questionnaire for National Security Positions" (OMB Control Number 3206-0005). The recruiter enters the information from the SF-86 into the Air Force Recruiting Information Support System - Total Force (AFRISS-TF). The recruiter then provides the applicant with the Agency Disclosure Notice and Privacy Act Statement for AFRISS-TF (see page 2) then proceeds to complete the remaining fields (see screen shots below). They are either filled out by the recruiter (because they are internal use only) or the recruiter asks the applicant for their responses. The system is logically organized and the tabs flow left to right. OMB CONTROL NUMBER: 0701-0150 OMB EXPIRATION DATE: MM/DD/YYYY AGENCY DISCLOSURE NOTICE The public reporting burden for this collection of information, 0701-0150, is estimated to average 180 minutes per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding the burden estimate or burden reduction suggestions to the Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, at whs.mc- [email protected]. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PRIVACY ACT STATEMENT: The following information is provided to comply with the Privacy Act (PL93-579). -

Our First Seven Years the New Park Street Pulpit 1 OUR FIRST SEVEN YEARS

Our First Seven Years The New Park Street Pulpit 1 OUR FIRST SEVEN YEARS A SERMON DELIVERED BY C. H. SPURGEON FROM THE SWORD AND THE TROWEL MAGAZINE APRIL, 1876 IT is not to be expected that we should write the story of our own personal ministry—this must be left to other pens, if it be thought worthwhile to write it at all. We could not turn these pages into an autobiography, nor could we very well ask any one else to write about us, and therefore we shall simply give bare facts and extracts from the remarks of others. On one of the last Sabbaths of the month of December, 1853, C. H. Spurgeon, being then nineteen years of age, preached in New Park Street Chapel in response to an invitation which, very much to his surprise, called him away from a loving people in Waterbeach near Cambridge, to supply a London pulpit. The congregation was a mere handful. The chapel seemed very large to the preacher and very gloomy, but he stayed himself on the Lord and delivered his message from James 1:17. There was an improvement even on the first evening and the place looked more cheerful. The text was, “They are without fault before the throne of God.” In answer to earnest requests, C. H. Spurgeon agreed to preach in London on the first, third, and fifth Sundays in January, 1854, but before the last of these Sabbaths, he had received an invitation, dated January 25, inviting him to occupy the pulpit for six months upon probation. -

Baptist History and Their Distinctives Lesson #5 – Who’S Who Amongst the Baptists?

Baptist History and Their Distinctives Lesson #5 – Who’s Who Amongst the Baptists? We Baptists are not very good at remembering our history. As a result, we often don’t know and appreciate the legitimacy or the basis of our own heritage. In this lesson, I wanted to familiarize you with some of our Baptist heroes and what they accomplished for us. It is important to understand that the nature of the contributions of these men are: 1. Developing our identity in doctrine and practice as to who we are. 2. Opposing false ideas regarding doctrine and practice. (Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy) 3. Preaching, teaching, publishing, organizing for the Kingdom of God. 4. Demonstrating leadership* in order to convince people regarding what we are and what we need to be. * “Leadership” – the ability to sell a vision. The Church is always under attack from Satan, his demons, and the culture at large. We must be ever vigilant regarding the truth. • Sometimes the attack comes abruptly and powerfully in the form of overt persecution. • Sometimes the attack comes subtly and slowly with flattery and deception that is barely detectable. Both of these forms of attack can and do kill churches! This is a partial list of important men as it would be much too time consuming to include all of these men and women who made us who we are today. I. Historical Heroes – (1600 - 1900) Obadiah Holmes – (1606 – 1682) A Rhode Island clergyman who was pivotal in the establishment of the Baptist Church in America. 2nd pastor of the First Baptist Church of Rhode Island. -

Charles H Spurgeon - the Puritan Prince of Preachers - Reformation Society

Charles H Spurgeon - The Puritan Prince of Preachers - Reformation Society <p><em>This article is also available in PowerPoint format <a href="http://www.slideshare.net/frontfel/charles-spurgeon-the-puritan-prince-of-preachers-17105 128">here</a>.</em></p> <p>In an age of great preachers the greatest was Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892).</p> <p><img class="caption" src="images/stories/People/Spurgeon_web.jpg" alt="CH Spurgeon" title="CH Spurgeon" align="right" height="145" border="0" width="165" /></p> <p>Born and raised in rural Essex, Charles Spurgeon came from a line of solid dissenting ancestors. Both his father and his grandfather were independent congregational ministers. Charles was born in 1834 in Kelvedon, Essex, an area with a long tradition of Protestant resistance to Catholicism dating back to the persecutions of <em>�Bloody Mary�</em> in the 16 th century.</p> <h3>A Son of the Manse</h3> <p>Charles was a <em>�son of the manse.�</em> His earliest childhood memories were of listening to sermons, learning Hymns and looking at the pictures in <em>The Pilgrim�s Progress</em> and <em>Foxe�s Book of Martyrs</em>. Charles first read <em>The Pilgrim�s Progress</em> at age six and went on to read it over 100 times. He would later recommend <em>Foxe�s Book of Martyrs</em> as<em> �the perfect Christmas gift for a child.�</em> He regarded <em>Foxe�s Book of Martyrs</em> as one of the most significant books he ever read. It vividly shaped his attitudes towards established religions, the tyranny of Rome and the glory of the Reformation.