Notes on William Gibson, the Peripheral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigori

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigorios Iliopoulos A thesis submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English and American Studies. Supervisor: Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou June 2020 Iliopoulos 2 Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between space and technology as well as the re-purposing of tangible and intangible materials in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and Virtual Light (1993). With attention paid to the importance of the cyberpunk setting. Gibson approaches marginal spaces and the re-purposing that takes place in them. The current thesis particularly focuses on spotting the different kinds of re-purposing the two works bring forward ranging from body alterations to artificial spatial structures, so that the link between space and the malleability of materials can be proven more clearly. This sheds light not only on the fusion and intersection of these two elements but also on the visual intensity of Gibson’s writing style that enables readers to view the multiple re-purposings manifested in thε pages of his two novels much more vividly and effectively. Iliopoulos 3 Keywords: William Gibson, cyberspace, utilization of space, marginal spaces, re-purposing, body alteration, technology Iliopoulos 4 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou, for all her guidance and valuable suggestions throughout the writing of this thesis. I would also like to express my gratitude to my parents for their unconditional support and understanding. -

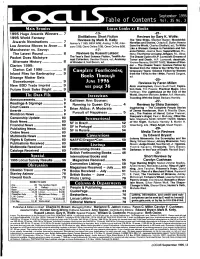

Table of Contents Vol. 35 No. 3

September 1995 Table of Contents vol. 35 no. 3 M a i n S t o r ie s Locus Looks a t Books 1995 Hugo Awards Winners... 7 - 13- - 21 - 1995 World Fantasy Distillations: Short Fiction Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe: Reviews by Mark R. Kelly: The Time Ships, Stephen Baxter; Bloodchild: Awards Nominations .............. 7 Asimov’s 11/95; F&SF 8/95; Analog 11/95; Inter Novellas and Stories, Octavia E. Butler; How to Lou Aronica Moves to Avon.... 8 zone 7/95; Omni Online 7/95; Omni Online 8/95. Save the World, Charles Sheffield, ed.; To Write Like a Woman: Essays in Feminism and Sci Manchester vs. Savoy: - 17- ence Fiction, Joanna Russ; Superstitious, R.L. The Latest Round..................... 8 Reviews by Russell Letson: Stine; The Horror at Camp Jellyjam, R.L. Stine; Pocket Does McIntyre The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Twelfth An The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of nual Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed ; Anatomy Terror and Death, H.P. Lovecraft; deadrush, Alternate History...................... 8 of Wonder 4, Neil Barron, ed. Yvonne Navarro; SHORT TAKE: Women of Won Clarion 1995; der - The Classic Years: Science Fiction by Women from the 1940s to the 1970s/The Con Clarion Call 1996 .................... 8 C o m p l ete For t hcoming temporary Years: Science Fiction by Women Inland Files for Bankruptcy ...... 9 from the 1970s to the 1990s, Pamela Sargent, Strange Matter Gets Books Thr ough ed. -25- Goosebumps.............................. 9 June 1996 Reviews by Faren Miller: New BDD Trade Imprint ........... 9 See p age 3 6 Alvin Journeyman, Orson Scott Card; Expira Future Book Sales Bright......... -

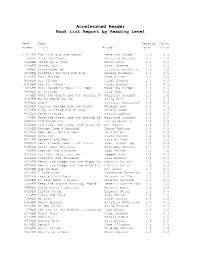

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

Science Fiction Review 30 Geis 1979-03

MARCH-APRIL 1979 NUMBER 30 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 Interviews: JOAN D. VINGE STEPHEN R. DONALDSON NORMAN SPINRAD Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. Be* 11408 MARCH, 1979 — VOL.8, no.2 Portland, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 30 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher CONFUCIUS SAY MAN WHO PUBLISHES FANZINES ALL LIFE DOOMED TO PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY SEEK MIMEOGRAPH IN HEAVEN, HEKTO- COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. Based on "Hellhole" by David Gerrold GRAPH IN HELL (To appear in ASIMOV'S SF MAGAZINE) SINGLE COPY — $1.50 ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor........... 4 PUOTE: (503) 282-0381 INTERVIEW WITH JOAN D. VINGE CONDUCTED BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER....8 LETTERS---------------- THE VIVISECTOR GEORGE WARREN........... A COLUMN BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER. .. .14 JAMES WILSON............. PATRICIA MATTHEWS. POUL ANDERSON........... YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS WORLD # 2-8-79 ORSON SCOTT CARD.. A REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION LAST-MINUTE NEWS ABOUT GALAXY BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................20 NEAL WILGUS................ DAVID GERROLD........... Hank Stine called a moment ago, to THE AWARDS ARE Ca-IING!I! RICHARD BILYEU.... say that he was just back from New York and conferences with the pub BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................24 GEORGE H. SCITHERS ARTHUR TOFTE............. lisher. [That explains why his INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN R. DONALDSON ROBERT BLOCH.............. phone was temporarily disconnected.] The GAIAXY publishing schedule CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.......................26 JONATHAN BACON.... SAM MOSKOWITZ........... is bi-monthly at the moment, and AND THEN I READ.... DARRELL SCHWEITZER there will be upcoming some special separate anthologies issued in the BOOK REVIEWS BY THE EDITOR..................31 CHARLES PLATT.......... -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

The Peripheral Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PERIPHERAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Gibson | 400 pages | 01 Nov 2014 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780670921560 | English | London, United Kingdom The Peripheral PDF Book We are experiencing technical difficulties. If the first 50 pages of a book are so garbled with terms context can't help a reader unravel, then they're going to put the book down and never come back to it. So here we are thirty years later, William Gibson is 66 years old, and has just published his eleventh novel although I want to say twelve, but Burning Chrome is actually short stories. She's clear and easy to hear. This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. And Amazon has been betting big on lofty sci-fi and fantasy projects. Hobbled, naked, into the bathroom. Returning from his trip, Burton tells Flynne that Milagros Coldiron wants to speak with her. October Streaming Picks. It would be cool to see Flynne again. The end. Please try again later. Gibson does the exact same, and this is why, in his own words, his writing process is painstakingly slow. Honestly the exercise only served to provide evidence that the action and description in this novel were poorly balanced. Imagining how that technology would work — what would be funny about it and what would be disorienting and queasy-making — is one of the absolute triumphs of this book. His eyes, a size too large for their sockets, felt gritty. Archived from the original on September 16, She read me the questions and entered my answers into the quiz so I did not actually have to stand up and ruin my achievement of perfect sloth. -

Guided Reading Book List

Title Author Level Anno’s Counting Book Mitsumasa Anno A Count and See Tana Hoban A Dig, Dig Leslie Wood A Do You Want to Be My Friend? Eric Carle A Flowers Karen Hoenecke A Growing Colors Bruce McMillan A In My Garden Moria McLean A Look What I Can Do Jose Aruego A Sea Shapes Suse MacDonald A Taking a Walk Rebecca Emberley A What Do Insects Do? S. Canizares & P. Chanko A What Has Wheels? Karen Hoenecke A Getting There Young B Hats Around the World Liza Charlesworth B Have You Seen My Cat? Eric Carle B Have You Seen My Duckling? Nancy Tafuri B Here’s Skipper Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B How Many Fish? Caron Lee Cohen B I Can Help Stan Wilhelm B I Can Write, Can You? Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B Let’s Go Visiting Sue Williams B Look, Look, Look Tana Hoban B Mommy, Where Are You? Ziefert & Boon B Runaway Monkey Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B So Can I Margery Facklam B Sunburn Ann Prokopchak B Thank You Betsey Chessen B Two Points J. Kennedy & A. Eaton B Under the Bed Bruce Larkin B Water/Who Lives in a Tree?/Who Lives in the Arctic Susan Canizares B Title Author Level All Fall Down Brian Wildsmith C Apples Deborah Williams C Bears Bobbie Kalman C Big Long Animal Song Mike Artwell C Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Bill Martin C Cats Deborah Williams C I See Monkeys Deborah Williams C I Want a Pet Barbara Gregorich C I Want To Be a Clown Sharon Johnson C Joshua James Likes Trucks Catherine Petrie C Leaves Karen Hoenecke C Looking for Halloween Karen Evans C Monsters Diane Namm C My Kite Deborah Williams C Octopus Goes to School Carolyn Bordelon C One Hunter Pat Hutchins C Pancakes for Breakfast Tomie dePaola C Rain R. -

A Postmodern Study on Gibsonian Space in Neuromancer Ms

Running Head: THE SINISTER LABYRINTH: A POSTMODERN STUDY ON GIBSONIAN 10 ICLLCE 2018 - 049 Jincy Joseph The Sinister Labyrinth: A Postmodern Study on Gibsonian Space in Neuromancer Ms. Jincy Joseph, Research Scholar Department of English Language and Literature St. Thomas College, Pala M.G University Kottayam Kerala, India Abstract The computer networking era caused a new vision or the transformation in many aspects of our lives. In 1980’s Gibson changed science fiction genre forever by his classical hit Neuromancer. Cyber literature is a concept derived from the digital literature, that is, the literature created on the computer and presented by the means of computer. Cyberspace is a virtual space where identity is fluid. Cyberpunk fiction analyse the existent human situation with the help of new technologies even if their settings are in the future. William Gibson’s Neuromancer deals with present human condition in the age of information. William Gibson first introduced the concept of cyberspace in his work Neuromancer as “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators in every nation…” Gibson’s cyberspace is a fantasy world, which is very attractive and seductive to the senses. He uses the human-machine hybrids- cyborgs, as the characters in the novel. Cyberpunk is an expression of postmodernism. According to thinkers like Jean Baudrillard, Fredric Jameson and Francois Lyotard, postmodernism as discourse is the result of an entire array of changes. The postmodern thoughts like simulacra and heterotopia are well established in Neuromancer. The novel portrays the hero as an antihero, not to attain victory over the evil, but to survive, by using their intelligence in the oppressive world conditions. -

Postmodern Orientalism. William Gibson, Cyberpunk and Japan

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. POSTMODERN ORIENTALISM William Gibson, Cyberpunk and Japan A thesis presented in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Leonard Patrick Sanders 2008 ABSTRACT Taking the works of William Gibson as its point of focus, this thesis considers cyberpunk’s expansion from an emphatically literary moment in the mid 1980s into a broader multimedia cultural phenomenon. It examines the representation of racial differences, and the formulation of global economic spaces and flows which structure the reception and production of cultural practices. These developments are construed in relation to ongoing debates around Japan’s identity and otherness in terms of both deviations from and congruities with the West (notably America). To account for these developments, this thesis adopts a theoretical framework informed by both postmodernism as the “cultural dominant” of late capitalism (Jameson), and orientalism, those discursive structures which produce the reified polarities of East versus West (Said). Cyberpunk thus exhibits the characteristics of an orientalised postmodernism, as it imagines a world in which multinational corporations characterised as Japanese zaibatsu control global economies, and the excess of accumulated garbage is figured in the trope of gomi. It is also postmodernised orientalism, in its nostalgic reconstruction of scenes from the residue of imperialism, its deployment of figures of “cross-ethnic representation” (Chow) like the Eurasian, and its expressions of a purely fantasmatic experience of the Orient, as in the evocation of cyberspace. -

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 74604EN 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5.0 9.0 107287EN 15 Minutes Steve Young 4.0 4.0 44802EN 1609: Winter of the Dead Elizabeth Massie 6.1 8.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 3.8 1.0 71428EN 95 Pounds of Hope Gavalda/Rosner 4.3 2.0 82655EN "A" Is for Alibi Sue Grafton 5.4 12.0 6030EN Abduction Mette Newth 6.0 8.0 81642EN Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6.0 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3.0 65575EN Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16.0 86479EN Abner & Me: A Baseball Card Adve Dan Gutman 4.2 5.0 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't R Debbie Dadey 4.0 1.0 14931EN The Abominable Snowman of Pasade R.L. Stine 3.0 3.0 34799EN About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9.0 54089EN Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7.0 29341EN Abraham's Battle Sara Harrell Banks 5.3 2.0 73206EN Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7.0 5251EN An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11.0 5252EN Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6.0 6001EN Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3.0 24909EN Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4.0 5253EN The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2.0 8452EN Across America on an Emigrant Tr Jim Murphy 7.8 3.0 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10.0 88997EN Across the Wall: A Tale of the A Garth Nix 6.5 12.0 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory 5.5 4.0 36046EN -

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 12 (Autumn 2018) Special Issue (Re)Examining William Gibson Edited by Paweł Frelik and Anna Krawczyk-Łaskarzewska Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 12 (Autumn 2018) Special Issue (Re)Examining William Gibson Edited by Paweł Frelik and Anna Krawczyk-Łaskarzewska Warsaw 2018 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Katherine E. Bishop, Ewa Kujawska-Lis, Keren Omry, Agata Zarzycka TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Photo by Viktor Juric on Unsplash ISSN 1733-9154 eISSN 2544-8781 PUBLISHER Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02-653 Warsaw paas.org.pl Nakład 160 egz. Wersją pierwotną Czasopisma jest wersja drukowana. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents Paweł Frelik Introducing William Gibson. Or Not ...................................................................... 271 Lil Hayes The Future’s Overrated: How History and Ahistoricity Collide in William Gibson’s Bridge Trilogy ............................................................. 275 Zofia Kolbuszewska