Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brain in a Vat in Cyberpunk: the Persistence of the Flesh

Stud. Hist. Phil. Biol. & Biomed. Sci. 35 (2004) 287–305 www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc The brain in a vat in cyberpunk: the persistence of the flesh Dani Cavallaro 1 Waterside Place, London NW1 8JT, UK Abstract This essay argues that the image of the brain in a vat metaphorically encapsulates articu- lations of the relationship between the corporeal and the technological dimensions found in cyberpunk fiction and cinema. Cyberpunk is concurrently concerned with actual and imaginary metamorphoses of biological organisms into machines, and of mechanical appara- tuses into living entities. Its recurring representation of human beings hooked up to digital matrices vividly recalls the envatted brain activated by electric stimuli, which Hilary Putnam has theorized in the context of contemporary epistemology. At the same time, cyberpunk imaginatively raises the same epistemological questions instigated by Putnam. These concern the cognitive processes associated with the collusion of human and mechanical creatures, and related metaphysical and ethical issues spawned by such processes. As a philosophical trope, the brain in a vat would appear to pivot on the notion of a disembodied subject consisting of sheer mentation. However, literary and cinematic interpretations of the image in cyberpunk persistently foreground the obdurate materiality of the flesh—often in its most grisly and grotesque incarnations. # 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Brains in vats; Materiality; Disembodiment; Cyborgs; Cyberpunk What is here proposed is that the brain in a vat image, an important trope in contemporary epistemology, is also an intriguing metaphor for one of cyberpunk’s pivotal preoccupations: namely, the relationship between the body and technology. -

Oblivion's Edge Jeremy Strandberg

Lawrence University Lux Lawrence University Honors Projects 5-12-1998 Oblivion's Edge Jeremy Strandberg Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Liberal Studies Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Strandberg, Jeremy, "Oblivion's Edge" (1998). Lawrence University Honors Projects. 53. https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp/53 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lawrence University Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ivion's Jeremy Strandberg Submitted for Honors in Independent Study 5/12/98 Prof. Candice Bradley, Advisor The year is 2042 ... ( Tech no Io g y i s a part of us ... High tech is stylish and chic. Computers have crept into every aspect of life, and billions of users are jacked brain frrst into the internet. Biosculpting can make people look any way they desire. Cybernetic implants-eyes, ears, and prosthetic limbs-break the limits of the human form. Biotechnology feeds billions while saving the lives of millions more. The train from New York to Miami takes under three hours, and there's a bustling tourist trade on Luna. The Veil has thinned ... Supernatural and paranormal phenomena are on the rise. There has been a resurgence of spirituality and superstition. Meditation is taught in grade school Psychic powers are accepted as fact, and most people have encountered a ghost or spirit at least once. Alchemists and fringe scientists are kept on salary by corporations. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

The Machineries of Uncivilization: Technology and the Gendered Body

The Machineries of Uncivilization: Technology and the Gendered Body in the Fiction of Margaret Atwood and William Gibson by Annette Lapointe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Annette Lapointe For Patricia Lapointe reader, teacher, literary guide my mom Table of Contents Acknowledgements iv Abstract v Introduction Factory Girl @ the Crossroads 1 Chapter 1 Cyborg Pathology: Infection, Pollution, and Material Femininity in Tesseracts 2 15 Chapter 2 Girls on Film: Photography, Pornography, and the Politics of Reproduction 56 Chapter 3 Meat Puppets: Cyber Sex Work, Artificial Intelligence, and Feminine Existence 96 Chapter 4 Manic Pixie Dream Girls: Viral Femininity, Virtual Clones, and the Process of Embodiment 138 Chapter 5 Woman Gave Names to All the Animals: Food, Fauna, and Anorexia 178 Chapter 6 The Machineries of Uncivilization: Gender, Disability, and Cyborg Identity 219 Conclusion New Maps for These Territories 257 Works Cited 265 iii Acknowledgements Many thanks to Dr. Mark Libin, my dissertation adviser, for all of his guidance in both my research and my writing. Dr Arlene Young guided me to a number of important nineteenth century texts on gender and technology. My foray into disability studies was assisted by Dr. Nancy Hansen and by Nadine Legier. melanie brannagan-frederiksen gave me insight into the writings of Walter Benjamin. Patricia Lapointe read every draft, provided a sounding board and offered a range of alternate perspectives. The Histories of the Body Research Group guided me through to literary and non-literary approaches to body studies. -

"The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital"

"The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital" http://reconstruction.eserver.org/043/leaver.htm Ever since William Gibson coined the term "cyberspace" in his debut novel Neuromancer , his work has been seen by many as a yardstick for postmodern and, more recently, posthuman possibilities. This article critically examines Gibson's second trilogy ( Virtual Light , Idoru and All Tomorrow's Parties ), focusing on the way digital technologies and identity intersect and interact, with particular emphasis on the role of embodiment. Using the work of Donna Haraway, Judith Butler and N. Katherine Hayles, it is argued that while William Gibson's second trilogy is infused with posthuman possibilities, the role of embodiment is not relegated to one choice among many. Rather the specific materiality of individual existence is presented as both desirable and ultimately necessary to a complete existence, even in a posthuman present or future. "The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital": Posthuman Possibilities, Embodiment and Technology in William Gibson's Interstitial Trilogy Tama Leaver Communications technologies and biotechnologies are the crucial tools recrafting our bodies. --- Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto" She is a voice, a face, familiar to millions. She is a sea of code ... Her audience knows that she does not walk among them; that she is media, purely. And that is a large part of her appeal. --- William Gibson, All Tomorrow's Parties <1> In the many, varied academic responses to William Gibson's archetypal cyberpunk novel Neuromancer , the most contested site of meaning has been Gibson's re-deployment of the human body. Feminist critic Veronica Hollinger, for example, argued that Gibson's use of cyborg characters championed the "interface of the human and the machine, radically decentring the human body, the sacred icon of the essential self," thereby disrupting the modernist and humanist dichotomy of human and technology, and associated dualisms of nature/culture, mind/body, and thus the gendered binarism of male/female (33). -

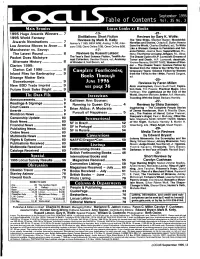

Table of Contents Vol. 35 No. 3

September 1995 Table of Contents vol. 35 no. 3 M a i n S t o r ie s Locus Looks a t Books 1995 Hugo Awards Winners... 7 - 13- - 21 - 1995 World Fantasy Distillations: Short Fiction Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe: Reviews by Mark R. Kelly: The Time Ships, Stephen Baxter; Bloodchild: Awards Nominations .............. 7 Asimov’s 11/95; F&SF 8/95; Analog 11/95; Inter Novellas and Stories, Octavia E. Butler; How to Lou Aronica Moves to Avon.... 8 zone 7/95; Omni Online 7/95; Omni Online 8/95. Save the World, Charles Sheffield, ed.; To Write Like a Woman: Essays in Feminism and Sci Manchester vs. Savoy: - 17- ence Fiction, Joanna Russ; Superstitious, R.L. The Latest Round..................... 8 Reviews by Russell Letson: Stine; The Horror at Camp Jellyjam, R.L. Stine; Pocket Does McIntyre The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Twelfth An The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of nual Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed ; Anatomy Terror and Death, H.P. Lovecraft; deadrush, Alternate History...................... 8 of Wonder 4, Neil Barron, ed. Yvonne Navarro; SHORT TAKE: Women of Won Clarion 1995; der - The Classic Years: Science Fiction by Women from the 1940s to the 1970s/The Con Clarion Call 1996 .................... 8 C o m p l ete For t hcoming temporary Years: Science Fiction by Women Inland Files for Bankruptcy ...... 9 from the 1970s to the 1990s, Pamela Sargent, Strange Matter Gets Books Thr ough ed. -25- Goosebumps.............................. 9 June 1996 Reviews by Faren Miller: New BDD Trade Imprint ........... 9 See p age 3 6 Alvin Journeyman, Orson Scott Card; Expira Future Book Sales Bright......... -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

Science Fiction Review 30 Geis 1979-03

MARCH-APRIL 1979 NUMBER 30 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 Interviews: JOAN D. VINGE STEPHEN R. DONALDSON NORMAN SPINRAD Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. Be* 11408 MARCH, 1979 — VOL.8, no.2 Portland, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 30 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher CONFUCIUS SAY MAN WHO PUBLISHES FANZINES ALL LIFE DOOMED TO PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY SEEK MIMEOGRAPH IN HEAVEN, HEKTO- COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. Based on "Hellhole" by David Gerrold GRAPH IN HELL (To appear in ASIMOV'S SF MAGAZINE) SINGLE COPY — $1.50 ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor........... 4 PUOTE: (503) 282-0381 INTERVIEW WITH JOAN D. VINGE CONDUCTED BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER....8 LETTERS---------------- THE VIVISECTOR GEORGE WARREN........... A COLUMN BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER. .. .14 JAMES WILSON............. PATRICIA MATTHEWS. POUL ANDERSON........... YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS WORLD # 2-8-79 ORSON SCOTT CARD.. A REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION LAST-MINUTE NEWS ABOUT GALAXY BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................20 NEAL WILGUS................ DAVID GERROLD........... Hank Stine called a moment ago, to THE AWARDS ARE Ca-IING!I! RICHARD BILYEU.... say that he was just back from New York and conferences with the pub BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................24 GEORGE H. SCITHERS ARTHUR TOFTE............. lisher. [That explains why his INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN R. DONALDSON ROBERT BLOCH.............. phone was temporarily disconnected.] The GAIAXY publishing schedule CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.......................26 JONATHAN BACON.... SAM MOSKOWITZ........... is bi-monthly at the moment, and AND THEN I READ.... DARRELL SCHWEITZER there will be upcoming some special separate anthologies issued in the BOOK REVIEWS BY THE EDITOR..................31 CHARLES PLATT.......... -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

The Peripheral Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PERIPHERAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Gibson | 400 pages | 01 Nov 2014 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780670921560 | English | London, United Kingdom The Peripheral PDF Book We are experiencing technical difficulties. If the first 50 pages of a book are so garbled with terms context can't help a reader unravel, then they're going to put the book down and never come back to it. So here we are thirty years later, William Gibson is 66 years old, and has just published his eleventh novel although I want to say twelve, but Burning Chrome is actually short stories. She's clear and easy to hear. This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. And Amazon has been betting big on lofty sci-fi and fantasy projects. Hobbled, naked, into the bathroom. Returning from his trip, Burton tells Flynne that Milagros Coldiron wants to speak with her. October Streaming Picks. It would be cool to see Flynne again. The end. Please try again later. Gibson does the exact same, and this is why, in his own words, his writing process is painstakingly slow. Honestly the exercise only served to provide evidence that the action and description in this novel were poorly balanced. Imagining how that technology would work — what would be funny about it and what would be disorienting and queasy-making — is one of the absolute triumphs of this book. His eyes, a size too large for their sockets, felt gritty. Archived from the original on September 16, She read me the questions and entered my answers into the quiz so I did not actually have to stand up and ruin my achievement of perfect sloth. -

Cyborg Fictions: the Cultural Logic of Posthumanism

CYBORG FICTIONS: THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF POSTHUMANISM Scott McCracken the fin-de-si2cle crisis in socialism has coincided with the reappearance of the cyborg. Cyborgs are everywhere, in films, fiction, politics and theory. Three strands of cyborg discourse can be identified. First, there is the use of the cyborg to represent the increasingly complex relationship between humanity and technology. Implants, transplants, prostheses, hormonal treatment, cosmetic surgery and genetic engineering all blur the boundary between body and machine. Second, there are cyborg fictions: the narra- tives that explore the imaginative possibilities inspired by new technology. These include the cyberpunk fiction of William Gibson and films like Terminator and Terminator II. Thirdly, there are the theoretical extrapola- tions of these fictions which map the relationship between the inhuman, global systems of the new world (dis)order and the kinds of hybrid identities that are one of its characteristics. Here the most influential writer is Donna Haraway, who sparked many of the critical debates with her article, 'A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the 80s', first published in Socialist Review.' Haraway is a historian of science who has devoted most of her work to interrogating that concept of the human which acts as an unquestioned assumption in most scientific research. Her cyborg project contains three central elements. Firstly, she wants to problematise identities rather than reinforcing them. In her 'Cyborg Manifesto', she describes herself as 'Once upon a time, in the 1970s . a proper, US socialist-feminist, white, female, hominid biologist, who became a historian of science to write about modern Western accounts of monkeys, apes, and women'. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type ofcomputer printer. The quality ofthis reproduction is dependent upon the quality ofthe copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann AIbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313n61-4700 8001521-0600 ='n..7!!TI!I!:l~.•.,-.....,.'~_,_,_ - _ _ _._ - .._----- THE FUTURE OF WORK AND DISABILITY: POLICY AND SCENARIOS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE MAY 1996 By: Robin L.