Several Authors Blank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burning Chrome Pdf Book by William Gibson

Download Burning Chrome pdf book by William Gibson You're readind a review Burning Chrome ebook. To get able to download Burning Chrome you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Book File Details: Original title: Burning Chrome 224 pages Publisher: Harper Voyager; Reprint edition (July 29, 2003) Language: English ISBN-10: 0060539828 ISBN-13: 978-0060539825 Product Dimensions:5.3 x 0.5 x 8 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 9411 kB Description: Best-known for his seminal sf novel Neuromancer, William Gibson is actually best when writing short fiction. Tautly-written and suspenseful, Burning Chrome collects 10 of his best short stories with a preface from Bruce Sterling, now available for the first time in trade paperback. These brilliant, high-resolution stories show Gibsons characters and... Review: I love this book, and I recommend it strongly to anyone who has already read Neuromancer. Neuromancer is also amazing, and as a continuous novel has better continuity, world building and consistency compared to this collection of short stories. The strength of Burning Chrome is also the inherent weakness of a short story collection, that the stories... Ebook Tags: burning chrome pdf, short stories pdf, william gibson pdf, johnny mnemonic pdf, rose hotel pdf, new rose pdf, winter market pdf, belonging kind pdf, mona lisa pdf, gernsback -

Haitian Voudoun and the Matrix

The Ghost in the Machine : Haitian Voudoun and the Matrix Steve Mizrach William Gibson's Count Zero It would seem that there are no two things more distinct than the primal, mystic, organic world of Haitian Voudoun, and the detached, cool, mechanical world of the high-tech future. Yet William Gibson parlayed off the success of his first SF cyberpunk blockbuster Neuromancer to write a more complex, engaging novel in which these two worlds are rapidly colliding. In his novel Count Zero, we encounter teenage hacker extraordinaire Bobby Newmark, who goes by the handle "Count Zero". Bobby on one of his treks into cyberspace runs into something unlike any other AI (Artificial Intelligence) he's ever encountered - a strange woman, surrounded by wind and stars, who saves him from "flatlining". He does not know what it was he encountered on the net, or why it saved him from certain death. Later we meet Angie Mitchell, the mysterious girl whose head has been "rewired" with a neural network which enables her to "channel" entities from cyberspace without a "deck" - in essence, to be "possessed". Bobby eventually meets Beauvoir, a member of a Voudoun/cyber sect, who tells him that in cyberspace the entity he actually met was Erzulie, and that he is now a favorite of Legba, the lord of communication... Beauvoir explains that Voudoun is the perfect religion for this era, because it is pragmatic : "It isn't about salvation or transcendence. What it's about is getting things done". Eventually, we come to realize that after the fracturing of the AI Wintermute, who tried to unite the Matrix, the unified being split into several entities which took on the character of the various Haitian loa, for reasons that are never made clear. -

New Alt.Cyberpunk FAQ

New alt.cyberpunk FAQ Frank April 1998 This is version 4 of the alt.cyberpunk FAQ. Although previous FAQs have not been allocated version numbers, due the number of people now involved, I've taken the liberty to do so. Previous maintainers / editors and version numbers are given below : - Version 3: Erich Schneider - Version 2: Tim Oerting - Version 1: Andy Hawks I would also like to recognise and express my thanks to Jer and Stack for all their help and assistance in compiling this version of the FAQ. The vast number of the "answers" here should be prefixed with an "in my opinion". It would be ridiculous for me to claim to be an ultimate Cyberpunk authority. Contents 1. What is Cyberpunk, the Literary Movement ? 2. What is Cyberpunk, the Subculture ? 3. What is Cyberspace ? 4. Cyberpunk Literature 5. Magazines About Cyberpunk and Related Topics 6. Cyberpunk in Visual Media (Movies and TV) 7. Blade Runner 8. Cyberpunk Music / Dress / Aftershave 9. What is "PGP" ? 10. Agrippa : What and Where, is it ? 1. What is Cyberpunk, the Literary Movement ? Gardner Dozois, one of the editors of Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine during the early '80s, is generally acknowledged as the first person to popularize the term "Cyberpunk", when describing a body of literature. Dozois doesn't claim to have coined the term; he says he picked it up "on the street somewhere". It is probably no coincidence that Bruce Bethke wrote a short story titled "Cyberpunk" in 1980 and submitted it Asimov's mag, when Dozois may have been doing first readings, and got it published in Amazing in 1983, when Dozois was editor of1983 Year's Best SF and would be expected to be reading the major SF magazines. -

William Gibson Fonds

William Gibson fonds Compiled by Christopher Hives (1993) University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Biographical Sketch o Scope and Content o Notes File List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description William Gibson fonds. - 1983-1993. 65 cm of textual materials Biographical Sketch William Gibson is generally recognized as the most important science fiction writer to emerge in the 1980s. His first novel, Neuromancer, is the first novel ever to win the Hugo, Nebula and Philip K. Dick awards. Neuromancer, which has been considered to be one of the influential science fiction novels written in the last twenty-five years, inspired a whole new genre in science fiction writing referred to as "cyberpunk". Gibson was born in 1948 in Conway, South Carolina. He moved to Toronto in the late 1960s and then to Vancouver in the early 1970s. Gibson studied English at the University of British Columbia. He began writing science fiction short stories while at UBC. In 1979 Gibson wrote "Johnny Mnemonic" which was published in Omni magazine. An editor at Ace books encouraged him to try writing a novel. This novel would become Neuromancer which was published in 1984. After Neuromancer, Gibson wrote Count Zero (1986), Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988), and Virtual Light (1993). He collaborated with Bruce Sterling in writing The Difference Engine (1990). Gibson has also published numerous short stories, many of which appeared in a collection of his work, Burning Chrome (1986). Scope and Content Fonds consists of typescript manuscripts and copy-edited, galley or page proof versions of all five of Gibson's novels (to 1993) as well as several short stories. -

Science Fiction, Steampunk, Cyberpunk

SCIENCE FICTION: speculative but scientific plausability, write rationally, realistically about alternative possible worlds/futures, no hesitation, suspension of disbelief estrangement+cognition: seek rational understanding of NOVUM (D. Suvin—cognitive estrangement) continuum bw real-world empiricism & supernatural transcendentalism make the incredible plausible BUT alienation/defamiliarization effect (giant bug) Literature of human being encountering CHANGE (techn innovat, sci.disc, nat. events, soc shifts) origins: speculative wonder stories, antiquity’s fabulous voyages, utopia, medieval ISLAND story, scientifiction & Campbell: Hero with a 1000 Faces & Jules Verne, HG Wells (Time Machine, War of the Worlds, The Island of Dr Moreau), Mary Shelley (Frankenstein), Swift Gulliver’s Travels Imaginative, Speculative content: • TIME: futurism, alternative timeline, diff hist. past, time travel (Wells, 2001. A Space Odyssey) • SPACE: outer space, extra-terrestrial adventures, subterranean regions, deep oceans, terra incognita, parallel universe, lost world stories • CHARACTERS: alien life forms, UFO, AI, GMO, transhuman (Invisible Man), mad scientist • THEMES: *new scientific principles, *futuristic technology, (ray guns, teleportation, humanoid computers), *new political systems (post-apocalyptic dystopia), *PARANORMAL abilities (mindcontrol, telekinesis, telepathy) Parallel universe: alternative reality: speculative fiction –scientific methods to explore world Philosophical ideas question limits & prerequisites of humanity (AI) challenge -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

The Machineries of Uncivilization: Technology and the Gendered Body

The Machineries of Uncivilization: Technology and the Gendered Body in the Fiction of Margaret Atwood and William Gibson by Annette Lapointe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Annette Lapointe For Patricia Lapointe reader, teacher, literary guide my mom Table of Contents Acknowledgements iv Abstract v Introduction Factory Girl @ the Crossroads 1 Chapter 1 Cyborg Pathology: Infection, Pollution, and Material Femininity in Tesseracts 2 15 Chapter 2 Girls on Film: Photography, Pornography, and the Politics of Reproduction 56 Chapter 3 Meat Puppets: Cyber Sex Work, Artificial Intelligence, and Feminine Existence 96 Chapter 4 Manic Pixie Dream Girls: Viral Femininity, Virtual Clones, and the Process of Embodiment 138 Chapter 5 Woman Gave Names to All the Animals: Food, Fauna, and Anorexia 178 Chapter 6 The Machineries of Uncivilization: Gender, Disability, and Cyborg Identity 219 Conclusion New Maps for These Territories 257 Works Cited 265 iii Acknowledgements Many thanks to Dr. Mark Libin, my dissertation adviser, for all of his guidance in both my research and my writing. Dr Arlene Young guided me to a number of important nineteenth century texts on gender and technology. My foray into disability studies was assisted by Dr. Nancy Hansen and by Nadine Legier. melanie brannagan-frederiksen gave me insight into the writings of Walter Benjamin. Patricia Lapointe read every draft, provided a sounding board and offered a range of alternate perspectives. The Histories of the Body Research Group guided me through to literary and non-literary approaches to body studies. -

Souvenirs Du Futur Le Robot Dans Le Steampunk Français

Souvenirs Du futur Le robot dans le Steampunk Français SOREAU CAROLINE MEMOIRE DE MASTER 2 – SOUTENU EN MAI 2014 SOUS LA DIRECTION DE NICOLAS DEVIGNE ET EDDIE PANIER 1 Université de Valenciennes et du Hainaut-Cambrésis Faculté de Lettres Langues Arts et Sciences Humaines Département Arts Plastiques Page de garde : Didier Graffet, Notre Dame 1900, Acrylique sur toile 65 x 100 cm, 2013 2 3 Remerciements En préambule de ce mémoire, je tiens d'abord à remercier M. Nicolas DEVIGNE, qui s’est montré d’une grande disponibilité et d’une aide précieuse tout au long de mon Master et aux différentes étapes de la réalisation de ce mémoire. Pour sa rigueur et son exigence, aussi, qui m’ont poussée à toujours plus de réflexion. M. Eddie PANIER, pour sa confiance en mes capacités, ses encouragements et les lectures précieuses qu’il a pu me conseiller tout au long de ces deux années de travail. Mme. CHOMARAT-RUIZ, pour son engagement au sein du Master Recherche et ses nombreux conseils. Mes parents et mon compagnon, toujours présents, y compris quand je peine à avoir confiance en mon travail et à croire en moi, au point d’en devenir invivable (je plaide coupable !) Pour leurs longues heures passées à relire ces pages et à essayer de comprendre « l’obscur » mouvement steampunk dans le but de pouvoir toujours dialoguer avec l’automate que je deviens lorsque je travaille. Pour leur présence, tant dans les bons que dans les mauvais moments. Mes différents relecteurs, qui ont pris le temps de relever nombre de mes coquilles. -

3 Sprawl Space

3 Sprawl Space The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary lists the following under “sprawl”: 1 v.i. Orig., move the limbs in convulsive effort or struggle; toss about. Now, lie, sit, or fall with the limbs stretched out in an ungainly or awkward way; lounge, laze. […] b Of a thing: spread out or extend widely in a straggling way; be of untidily irregular form […]. (New Shorter OED 1993) The second part of the entry refers to the transitive verb, for which the agency has shifted semantically and lies elsewhere, as “sprawl(ing)” is inflicted on something, and “usu[ally] foll[owed] by out” (ibid.), sig- nalling the expansiveness of the motion. As a noun, “sprawl” also oc- curs in combination with “urban” (meaning “Of, pertaining to, or con- stituting a city or town”) which renders “urban sprawl” as “the uncon- trolled expansion of urban areas” (ibid.). Considering the etymology, one might think that the notion of “sprawl” has relaxed with regard to living subjects as actants. When it comes to things, however, dead matter comes to life, things seem to appropriate agency and expand, taking up more space; or they already are where they should not be. The resulting form is a disorderly one that deviates from an established order: “Sprawl” usually refers to an outward movement and is not perceived as very pleasant or becoming. In short, most of the above may already explain why “sprawl” is of in- terest to cyberpunk and to William Gibson in particular: matter ac- quires lifelike agency and potentially decenters the subject; it moves in space and upsets a given order; it is messy. -

"The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital"

"The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital" http://reconstruction.eserver.org/043/leaver.htm Ever since William Gibson coined the term "cyberspace" in his debut novel Neuromancer , his work has been seen by many as a yardstick for postmodern and, more recently, posthuman possibilities. This article critically examines Gibson's second trilogy ( Virtual Light , Idoru and All Tomorrow's Parties ), focusing on the way digital technologies and identity intersect and interact, with particular emphasis on the role of embodiment. Using the work of Donna Haraway, Judith Butler and N. Katherine Hayles, it is argued that while William Gibson's second trilogy is infused with posthuman possibilities, the role of embodiment is not relegated to one choice among many. Rather the specific materiality of individual existence is presented as both desirable and ultimately necessary to a complete existence, even in a posthuman present or future. "The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital": Posthuman Possibilities, Embodiment and Technology in William Gibson's Interstitial Trilogy Tama Leaver Communications technologies and biotechnologies are the crucial tools recrafting our bodies. --- Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto" She is a voice, a face, familiar to millions. She is a sea of code ... Her audience knows that she does not walk among them; that she is media, purely. And that is a large part of her appeal. --- William Gibson, All Tomorrow's Parties <1> In the many, varied academic responses to William Gibson's archetypal cyberpunk novel Neuromancer , the most contested site of meaning has been Gibson's re-deployment of the human body. Feminist critic Veronica Hollinger, for example, argued that Gibson's use of cyborg characters championed the "interface of the human and the machine, radically decentring the human body, the sacred icon of the essential self," thereby disrupting the modernist and humanist dichotomy of human and technology, and associated dualisms of nature/culture, mind/body, and thus the gendered binarism of male/female (33). -

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigori

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigorios Iliopoulos A thesis submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English and American Studies. Supervisor: Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou June 2020 Iliopoulos 2 Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between space and technology as well as the re-purposing of tangible and intangible materials in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and Virtual Light (1993). With attention paid to the importance of the cyberpunk setting. Gibson approaches marginal spaces and the re-purposing that takes place in them. The current thesis particularly focuses on spotting the different kinds of re-purposing the two works bring forward ranging from body alterations to artificial spatial structures, so that the link between space and the malleability of materials can be proven more clearly. This sheds light not only on the fusion and intersection of these two elements but also on the visual intensity of Gibson’s writing style that enables readers to view the multiple re-purposings manifested in thε pages of his two novels much more vividly and effectively. Iliopoulos 3 Keywords: William Gibson, cyberspace, utilization of space, marginal spaces, re-purposing, body alteration, technology Iliopoulos 4 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou, for all her guidance and valuable suggestions throughout the writing of this thesis. I would also like to express my gratitude to my parents for their unconditional support and understanding. -

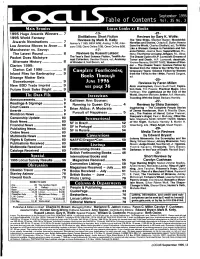

Table of Contents Vol. 35 No. 3

September 1995 Table of Contents vol. 35 no. 3 M a i n S t o r ie s Locus Looks a t Books 1995 Hugo Awards Winners... 7 - 13- - 21 - 1995 World Fantasy Distillations: Short Fiction Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe: Reviews by Mark R. Kelly: The Time Ships, Stephen Baxter; Bloodchild: Awards Nominations .............. 7 Asimov’s 11/95; F&SF 8/95; Analog 11/95; Inter Novellas and Stories, Octavia E. Butler; How to Lou Aronica Moves to Avon.... 8 zone 7/95; Omni Online 7/95; Omni Online 8/95. Save the World, Charles Sheffield, ed.; To Write Like a Woman: Essays in Feminism and Sci Manchester vs. Savoy: - 17- ence Fiction, Joanna Russ; Superstitious, R.L. The Latest Round..................... 8 Reviews by Russell Letson: Stine; The Horror at Camp Jellyjam, R.L. Stine; Pocket Does McIntyre The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Twelfth An The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of nual Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed ; Anatomy Terror and Death, H.P. Lovecraft; deadrush, Alternate History...................... 8 of Wonder 4, Neil Barron, ed. Yvonne Navarro; SHORT TAKE: Women of Won Clarion 1995; der - The Classic Years: Science Fiction by Women from the 1940s to the 1970s/The Con Clarion Call 1996 .................... 8 C o m p l ete For t hcoming temporary Years: Science Fiction by Women Inland Files for Bankruptcy ...... 9 from the 1970s to the 1990s, Pamela Sargent, Strange Matter Gets Books Thr ough ed. -25- Goosebumps.............................. 9 June 1996 Reviews by Faren Miller: New BDD Trade Imprint ........... 9 See p age 3 6 Alvin Journeyman, Orson Scott Card; Expira Future Book Sales Bright.........