Censorship: an Historical Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Huntz Hall Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Huntz Hall 电影 串行 (大全) Hold That Baby! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hold-that-baby%21-5879289/actors Smugglers' Cove https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/smugglers%27-cove-7546616/actors 'Neath Brooklyn Bridge https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%27neath-brooklyn-bridge-4540500/actors Spook Chasers https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/spook-chasers-7579083/actors Hold That Hypnotist https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hold-that-hypnotist-5879299/actors Triple Trouble https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/triple-trouble-12129783/actors Let's Go Navy! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/let%27s-go-navy%21-6532424/actors A Walk in the Sun https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-walk-in-the-sun-387832/actors Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/won-ton-ton%2C-the-dog-who-saved-hollywood-3569779/actors Saved Hollywood Bowery Blitzkrieg https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bowery-blitzkrieg-4950929/actors In Fast Company https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/in-fast-company-6009436/actors Bowery Buckaroos https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bowery-buckaroos-4950930/actors Crazy Over Horses https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/crazy-over-horses-5183226/actors Crashing Las Vegas https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/crashing-las-vegas-12110151/actors The Phynx https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-phynx-1936195/actors Ghosts on the Loose https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ghosts-on-the-loose-3104973/actors Blues Busters -

![Convention Speech Material 8/14/80 [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5369/convention-speech-material-8-14-80-1-1455369.webp)

Convention Speech Material 8/14/80 [1]

Convention Speech Material 8/14/80 [1] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: Convention Speech material 8/14/80 [1]; Container 171 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf . �- . "". ·· . · : . .... .... , . 1980 · DEMOCRATIC PLATFORM SUMMARY .··.. · I. ECONOMY··. Tliis was·· one.of ·the mOst .. dfffibult sections to develop in the way we. wan:ted,.>for there wei�· considerable ··.support among the Platform committee .members for a,' stronger·· ant-i�recession program than we have 'adopted. to date·. senator :Kennedy's $1.2.·bili'ion'·stimulus ·prOpof>al was v�ry · attraeffive to ·many .. CoiiUJlitte.e ine.�bers, but in the . end •We were able to hold our members.' Another major problem q()ri.cerned the frankness with which· we wanted to recognize our current ecohomic situation. we ultimately .decided, co:r-rectly I believe, to recognize that we are in a recession, that unemployment is rising, and that there are no easy solutions.to these problems. Finally, the Kennedy people repeatedly wanted to include language stating that no action would be taken which would have any significant increase in unemployment. We successfully resisted this .by saying no such action would be taken with that .intent or design, but Kennedy will still seek a majority plank at the Convention on this subject. A. Economic Strength -- Solutions to Our Economic Problems 1. Full Employment. There is a commitment to achieve the Humphrey�Hawkins goals, at the cu�rently pre scribed dates. we successfully resi�ted.effdrts:to move these goals back to those origiilally ·prescribed· by this legislation. -

(And Holmes Related) Films and Television Programs

Checklist of Sherlock Holmes (and Holmes related) Films and Television Programs CATEGORY Sherlock Holmes has been a popular character from the earliest days of motion pictures. Writers and producers realized Canonical story (Based on one of the original 56 s that use of a deerstalker and magnifying lens was an easily recognized indication of a detective character. This has led stories or 4 novels) to many presentations of a comedic detective with Sherlockian mannerisms or props. Many writers have also had an Pastiche (Serious storyline but not canonical) p established character in a series use Holmes’s icons (the deerstalker and lens) in order to convey the fact that they are acting like a detective. Derivative (Based on someone from the original d Added since 5-22-14 tales or a descendant) The listing has been split into subcategories to indicate the various cinema and television presentations of Holmes either Associated (Someone imitating Holmes or a a in straightforward stories or pastiches; as portrayals of someone with Holmes-like characteristics; or as parody or noncanonical character who has Holmes's comedic depictions. Almost all of the animation presentations are parodies or of characters with Holmes-like mannerisms during the episode) mannerisms and so that section has not been split into different subcategories. For further information see "Notes" at the Comedy/parody c end of the list. Not classified - Title Date Country Holmes Watson Production Co. Alternate titles and Notes Source(s) Page Movie Films - Serious Portrayals (Canonical and Pastiches) The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes 1905 * USA Gilbert M. Anderson ? --- The Vitagraph Co. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

Rigby Star 1947 05 29 Vol 45 No 22

THE RIGBY STAR, RIGBY, IDAHO Thursday, May 29, 1947 letter continued, "I believe it would action might be deferred tempor for the present," Dworshak's letter it Richard Norris, another newcomer to ive until they visit a sleuthing ag // 1 ency to collect pay owed Huntz Hall, be justifiable and wise to lift sugar arily until a more accurate picture concluded. the screen, as Abie, promises to shoot of the sugar industry is available. to stardom. Twin Bill At who has just been fired off the invest rationing to housewives immediately. Swell Guy igating staff. This would make possible conserva President Truman says that if con- Others in the film are Michael "Although you have authority un trol of the nation can be kept out of Chekhov, J. M. Kerrigan, Vera Gor Others in the film are Betty Comp- tion and canning of fruits which will der the existing sugar statute to lift son, Bobby Jordan, Gabriel Dell, Billy soon be available throughout the the hands of greedy people, there will At Main Sunday don, George E. Stone, Emory Par- Main This Week price controls prior to October 31, it be no economic collapse. Does that nell, Art Baker, Bruce Merritt, Eric Hit songs of the west vie with spec Benedict and David Gorcey. country. Starring Sonny Tufts and Ann "While it may also be desirable to is apparent that retention of these mean that the government will have Blythe in one of the most unusual Blore and Harry Hays Morgan. tacular, rough-and-tumble action price controls should be maintained to run itself? stories ever filmed, "Swell Guy," pro scenes and hilarious comedy sequenc Idaho Senator Urges lift conrtols of industrial users, such duced by Mark Hellinger shows Sun es for the top honors in "Trail To day at the Main Theatre. -

Looking at Hollywood ED SULLIVAN

Pa~e Two with Looking at Hollywood ED SULLIVAN ELLEN DREW LOUISE CAMPBELL ment store accounting clerk and .salesgirl. She has appeared in fourteen pictures, and in her last two pictures won featured bill- ing opposite Bing Crosby and Ronald Colman. Contrast this sensible treatment of a young- ster with the helter-skelter plan of naming her a star in her first appearance before cameras. WIWAM HOLDEN • • • At the moment, and from now studios. Technically the British on, the youngsters of the country pictures were inferior to those Northwestern un i vel'S i t y's will be in an advantageous made in Hollywood, but the tor- Lou i s e Campbell, instead 01 position if they have talent, be- eign pictures were crowded with Abo .•.•t being rushed into parts that cause the search has just started new laces. You didn't know in were too big for her, had the PATRICIA and It will continue for the next advance that a player would Studios Eye Future Through experience of seven pictures be- MORISON ROBERT PRESTON twelve months. The studios gesture this way or that, you hind her before she got an im- frankly are looking for replace- couldn't pre d i c t in advance picked the first thirteen of his portant par t in ••Men with ments. The knell has been where this one would sneer and Golden Circle of New Faces Golden Circle by audience reac- Wings." That is intelligent pro- sounded for those who have another one giggle, and the ex- tion throughout the country. -

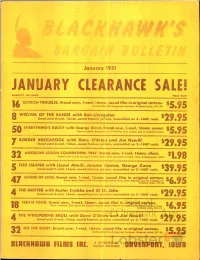

January Clearance Sale! Quantity on Hand Price Each ~ - -~· -··=~------,------Ostrich Troubles

" ,. ' ' ~ ' .• -~....:.r . ,; -~.. J • January 11951 JANUARY CLEARANCE SALE! QUANTITY ON HAND PRICE EACH ~ - -~· -··=~----------------,-------------------- OSTRICH TROUBLES. Brand new, 1-reel, 16mm. sound film in original cartons. ss.,s 16 Cr:st:e-Kiko the Ka .. garoo Cartoon. Original ptice, $17.50. WOLVES OF THE RANGE with Bob Living5ton s29 95 8 Good used 6-reel, 16mm. sound feature pici·ure, assembled on 2-1600' reels. e -~ ,..a:.;.;::::ii.:._.c __________________ ,________________ ,_,_ _ _,__ BORDER BUCKAROOS with Dave O'Brie11 and Jim Newill s29 95 7 Good used 6-reel, 16mm. sound feature picf·ure, assembled on 2-1600' reels. e AMERICAN LEGION CONVENTION, 1947. Rrcind new, 1-reel, 16mm. silent. SJ 98 32 Castle's film of the fun anc frivolity of 1h11 1947 convention in New York. Origi•al price, $8.75. • ------------~---~----~-·----·-----------~--- tOG ISLAND with Lionel Atwill, Jerome Cowan, George Zucco s39 95 5 Good used 7-reel, 16mm. sound faaf·ure pic~ure, assembled on 2-1600' reels. e SONGS OF LOVE. Brand new, 1-reel, 16mm. sound fiim in original cartons. S6 95 Castle Music Album with Gene G,-ounds, Syl-,ia Froos, Dove Schooler and his Swinghearts. • 47 Original price, $17.50. THE DRIFTER with Buster Crabbe and Al S·t. John s29 95 4 Good used 6-reel, 16mm. sound featura {'i :ture, assembled on 2-1600' reels. e FISH IS FOOD. Brand new, 1-reel, 16mm. s:u.,nd film in original cartons. S6 95 There's nothing fishy about the bargain quolit ) of this lilm on the Fulton Fish Market in New York. -

Tentative City Budget Figures out for Study Red Cross Drive

: ( ! M0' 15,000 People Read the HERALD. Published Every Tuesday "Justice to at!; and Friday. nens." SUMMIT RECORD FIFTY-SECOND YEAR. NO. 32 SUMMIT, N. J., FRIDAY MORNING, DECEMBER 13, 1940 $3.50 PER YEAR KHMINhKH TO (HAMBKK Give for Summit's To Plan Farewells to >'. I>. O.'HOLIDAY Tentative City OF COMMERCE MEMBERS IRAIMNW I'IMKiKA.H Former Willkie Christmas Dinner F**d Selective Service Men Christmas Programs To Call Twenty l"-ami|lf Lest the members of the Drills for N. D. O.'s Lilth- Budget Figures Chamber of" Commerce should Among the many appatte for The N*. D. O., the Local Defense In Public Schools 'I'liittsburi;' have been discon- forget, they arfe reminded to Club Reorganizing funds at this season, w« hop* Sum- Council, American Legion Sum- tiiiucd as) of this date until Per Cent, of Draft exercise their privilege to vote mit's under-privileged will not bemit I'ost No. 138, the V. F. \V.. the Thursday, January 2, 1941. Out For Study ^ior the five members of the overlooked. Red Cross and Mrs. William A. School Board Also Hears' Hi'gintiiiiK January 2. assem- Board of Directors of the On Permanent Basis There are three hundred families Becker, past president general of blies will be held at the VA\- January to June Chamber of Commerce. The in this classification In Summit— the p. A. R. have lieeu asked to be Of New Parking Rules i soir Junior IHKII SCIICHJI on' Ir.ii Wlllllil Council Awaits Changes voting closes on Monday, the some on relief and some In th« represented tonight at the office of sit j Tuosday and Thursday night 16th. -

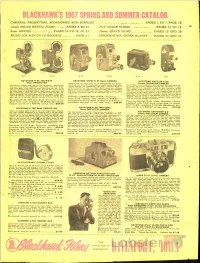

• (•- -•I• • ...PAGES 1 to 7, PAGE 15. 2"X2" COLOR SLIDES ..., ...PAGES 13 TO

CAMERAS, PROJECTORS, ACCESSORIES AND SUPPLIES . • (•- -•I• • ......... PAGES 1 TO 7, PAGE 15. 16mm. SOUND R ENTAL FILMS ... -c- · .PAGES 8 TO 12 2"x2" COLOR SLIDES . .... ......, ...... PAGES 13 TO 15. - 8mm. MOVIES . ·-· ..... •, •• . PAGES 16 TO 18, 20, 23 16mm. SOUND FILMS . ...••...• .PAGES 19 AND 20 MUSIC FOR MEN ON LP RECORDS. .PAGE 21 INFORMATION, ORDER BLANKS. PAGES 22 AND 23 K- 25 K-28 K-50 KEYSTONE K-95 750-WATT KEYSTONE CAPRI K-25 8mm. CAMERA KEYSTONE MAYFAIR K-50 8mm. PROJECTOR F'quippt d '1.Jlh t.2.S fhed rot:ui luh in inr~ rch:.;mg_eab l e l cn -, mounf 16mm. MAGAZINE CAMERA l ou'II )1..tH a britJi:,mt ,ibow "irh this 7~U-H:.itt JJl"i•~Cl<lt'. Pr«b10n-Jf~t <'. ,htle.d :1 nd '-oloc (;Offf.ctitd. t i'ndt'r ~,.,r~ni of $tenuine ,:round 0 1Hical ,tl -',"iS, Ju-.. 36-oun,:t < Ut m (nh.··t t:ilwi,- ta,.e. and perfection. N<',t- pu~IJi-buuon •,t,;. ,-ind and bt'a,_, . dit'·Ca.'i( con 0; troc1ion, mea11 rn1oc-uh, rock.-.Stt':..il,- pro~c l"~oot.1gt inflk1uor /\t'~ ;,uromarirally "l•t·n lilm is lnt;uted - ~ign:.l!i in Jtr p('1 mih r(·,::nlar- run, continuou:!t loc.:k·run (for !,(>1£-m·e, i~J Of' ~inklf lmn. Lift-o-m;Ui<" .!!" itch lurn.!t off room lir,::hts ,,ht'll ., 4 u tu111 on Iii~ t-"enr o r ncci,h.. 1lt::I jam. Threc,•W.t) 1r'i,rr.,·r control, regulur wn, (c)otinuous frame e~r>o'iUre (for .:-i top-mo11ou anim:dion>. -

The Irish-American Gangster in Film

Farrell 1 THE IRISH-AMERICAN GANGSTER IN FILM By Professor Steven G. Farrell 1 Farrell 2 When The Godfather was released in the early seventies, it effectively created a myth of the virtually unbeatable Italian crime family for the American public that endured for the remainder of the century. This film also effectively eliminated all other white ethnic organized gangs from the silver screen, as well as from the public’s eye. Hollywood, as we shall see, had their history wrong in this case. The Italian Mafia was never as invincible as Hollywood depicted it on film, nor did they always have everything their own way when it came to illegal activities. It wasn’t until the close of the last century that the film industry began to expose the old-time hoods as being fallible and besieged on all sides from new criminal elements connected with newly arrived immigrant groups. The Cubans, Russians and the Colombian hoods, along with the longer established African and Mexican American gangs, had begun to nibble away at the turf long controlled by the almighty Italian mob. As the paradigm of the urban underworld began to shift to reflect the new realities of the global economy, another look at the past by historians and Hollywood is revealing that the Italian gang never had absolute power as it was once commonly believed. The Irish hoodlums, to single out the subject of this paper, were actually engaged in gangland activities years before the arrival of the Italians and the Irish also competed with the Italians up until recently. -

Crime Wave for Clara CRIME WAVE

Crime Wave For Clara CRIME WAVE The Filmgoers’ Guide to the Great Crime Movies HOWARD HUGHES Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published in 2006 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Howard Hughes, 2006 The right of Howard Hughes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The TCM logo and trademark and all related elements are trademarks of and © Turner Entertainment Networks International Limited. A Time Warner Company. All rights reserved. © and TM 2006 Turner Entertainment Networks International Limited. ISBN 10: 1 84511 219 9 EAN 13: 978 1 84511 219 6 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Typeset in Ehrhardt by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, -

Classified by Genre: Rhetorical Genrefication in Cinema by © 2019 Carl Joseph Swanson M.A., Saint Louis University, 2013 B.L.S., University of Missouri-St

Classified by Genre: Rhetorical Genrefication in Cinema By © 2019 Carl Joseph Swanson M.A., Saint Louis University, 2013 B.L.S., University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2010 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Catherine Preston Co-Chair: Joshua Miner Michael Baskett Ron Wilson Amy Devitt Date Defended: 26 April 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Carl Joseph Swanson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Classified by Genre: Rhetorical Genrefication in Cinema Chair: Catherine Preston Co-Chair: Joshua Miner Date Approved: 26 April 2019 iii Abstract This dissertation argues for a rethinking and expansion of film genre theory. As the variety of media exhibition platforms expands and as discourse about films permeates a greater number of communication media, the use of generic terms has never been more multiform or observable. Fundamental problems in the very conception of film genre have yet to be addressed adequately, and film genre study has carried on despite its untenable theoretical footing. Synthesizing pragmatic genre theory, constructivist film theory, Bourdieusian fan studies, and rhetorical genre studies, the dissertation aims to work through the radical implications of pragmatic genre theory and account for genres role in interpretation, evaluation, and rhetorical framing as part of broader, recurring social activities. This model rejects textualist and realist foundations for film genre; only pragmatic genre use can serve as a foundation for understanding film genres. From this perspective, the concept of genre is reconstructed according to its interpretive and rhetorical functions rather than a priori assumptions about the text or transtextual structures.