Telecommunications and Developmentally Disabled People: Evaluations Of,Audio Conferencinv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Time Radio Club Established 1975

The Old Time Radio Club Established 1975 Number 355 December 2007 The fllustrated Pres« Membership Information Club Officers Club Membership: $18.00 per year from January 1 President to December 31. Members receive a tape library list Jerry Collins (716) 683-6199 ing, reference library listing and the monthly 56 Christen Ct. newsletter. Memberships are as follows: If you join Lancaster, NY 14086 January-March, $18.00; April-June, $14; July [email protected] September, $10; October-December, $7. All renewals should be sent in as soon as possible to Vice President & Canadian Branch avoid missing newsletter issues. Please be sure to notify us if you have a change of address. The Old Richard Simpson (905) 892-4688 Time Radio Club meets on the first Monday of the 960 16 Road RR 3 month at 7:30 PM during the months of September Fenwick, Ontario through June at St. Aloysius School Hall, Cleveland Canada, LOS 1CO Drive and Century Road, Cheektowaga, NY. There is no meeting during the month of July, and an Treasurer informal meeting is held in the month of August. Dominic Parisi (716) 884-2004 38 Ardmore PI. Anyone interested in the Golden Age of Radio is Buffalo, I\lY 14213 welcome. The Old Time Radio Club is affiliated with the Old Time Radio Network. Membership Renewals, Change of Address Peter Bellanca (716) 773-2485 Club Mailing Address 1620 Ferry Road Old Time Radio Club Grand Island, NY 14072 56 Christen Ct. [email protected] Lancaster, NY 14086 E-Mail Address Membership Inquires and OTR otrclub(@localnet.com Network Related Items Richard Olday (716) 684-1604 All Submissions are subject to approval 171 Parwood Trail prior to actual publication. -

Sunday, May 20, 1984 St

SUNDAY, MAY 20, 1984 ST. JOHN'S UNIVERSITY NEW YORK St. John's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Institute of Asian Studies School of Education and Human Services College of Business Administration College of Pharmacy and Allied Health Professions St. Vincent's College BACCALAUREATE MASS Sunday, May 20, 1984 PRINCIPAL CELEBRANT VERY REVEREND JOSEPH T. CAHILL, C.M. President DEDICATION OF ST. JOHN'S UNIVERSITY CON CELEBRANTS TO MARY IMMACULATE REVEREND THOMAS V. CONCAGH, C.M. Vice President for Auxiliary Services and Alumni Relations Mary, Mother of God, Holy Virgin, we, the Board of Trustees, administrators, faculty, and students of St.John's University, renew our filial and abiding love to you REVEREND JOSEPH V. DALY, C.M. Vice President for Campus Ministry at this Baccalaureate Mass, as we consecrate again our beloved University to you. With you, may we be consecrated completely to our Son, Christ our Lord, and like you, REVEREND JOSEPH I. DIRVIN, C.M. Vice President for University Relations and Secretary dedicated to fulfilling the will of Our Father. Our intentions in this dedication include our whole being-all that we have, all that we presently are, and especially all REVEREND WALTER F. GRAHAM, C.M. Vice President for Business Affairs and Treasurer that we ever hope to be. In our re-consecration, we ask you to reserve a special place in REVEREND THOMAS F. HOAR, C.M. your maternal heart for our benefactors, relatives and friends, without whose prayers Vice President for Liberal Arts and Sciences and and material assistance our noble commitments are impossible. -

News from the World. Nation & State

; ::; r;v ; 'n Rioting Spreads m *m:!*J ¦' ¦*?$¦•'' *%• " • ' • • / .• 'i •^ ^ ¦'ii;>^^ .:';;• .' • ' • •iV'•-^• J . P- ¦ ry™$?pm Police See No Conspiracy, To Dozen Cities 3 Substanial Leads' Reported By The Associated Press MEMPHIS, Tenn. (/P) — As the shot that three hours later from a distance of 205 feet, Racial violence struck more than a dozen U.S. cities killed Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. re- then disappared in the resulting confusion. yesterday with the worst burning and looting in the nation's verberated around the world yesterday, there The murder weapon was believed to be capital and Chicago, an angry aftermath to the slaying of were hints that authorities may be closing a newly purchased .30-. *6 Remington pump civil rights leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in on his stealthy assassin. rifle, discarded two doors away from the A 13-hour curfew from 5:30 p.m. to 6:30 a.m. was Atty. Gen. Ramsey Clark flew here from rooming house. ordered in Washington where 4,000 soldiers poured in to Washington and later told newsmen: "We've The threat of a blood bath was upper- protect the White House and the Capitol and stifle violence got some substantial leads. We're very hope- most in the minds of many persons in many that already spilled out of three Negro sections into the ful. We've got some good breaks. There is parts of the world, stunned at the slaying downtown area. Twenty-four hundred of the troops were no evidence at this time of any conspiracy." of King, the 1964 winner of the Nobel Peace regular Army soldiers from Fort Myer, Va. -

Education Committee Holds Conference Church Tower Crumbling

) fordham university, new york Education Committee Vigil Holds Conference Held Leadership Responsibility and Multi Culturalism Discussed By TOM MKLI.4NA By ELENA DB1ORE ing^" All of these workshops touched on the con- counseling center at St. John's University, and Students mid (acuity of I-onilMin UIMVMM The Education Committee and the Commit- cepts of race/ethnic groups, prejudice, and Gail Hawkins, director of students activities at ty, ulonj! with ihe pencral public, were in vital tee on Minority Programs of the Association of rascism. They also explored values, communica- the Community College of Philadelphia. by Rnsc Hill Campus Ministries In show their College Unions-International (ACU-I) Region 3 tions and awareness which are essential ID According to Michael Sullivan, assistant support to those affected by the AIDS crisis by held a conference entitled "Leadership Respon- developing effective multicultural programs on dean of students for students activities, about 75 .ilii:iidini> an all-mpht prayer vigil last I rulav sibility and Multiculturalism" last Friday on the individual campuses. Presenters at the afternoon people attended the.conference on Friday. Includ- night beginning al 9 p rn in ihc UmviMsity second floor of McGinley Center. workshops included Hector Oritz, associate dean ed were Dr. .Fred D. Phelps, dean of students Church. The day was divided into two sessions, mor- from Lehman College-CUNY, and assistant In a siaiiMiioM to the pros-; issued last wi-ek. ning and afternoon. The morning session (9:00 "Ml of these workshops directors of Activities from many other institu- Rev Paul W. Bryant, S.J . director of campus a.m. -

Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting Biotechnology In

FROM FLOOD TO FREE AGENCY: THE MESSERSMITH-MCNALLY ARBITRATION RECONSIDERED Henry D. Fetter* INTRODUCTION .............................................................................157 I. THE FLOOD CASE AND ITS AFTERMATH ...................................161 II. THE MESSERSMITH-MCNALLY ARBITRATION .......................... 165 III. PARAGRAPH 10(A) IN THE CURT FLOOD CASE ...................... 168 IV. THE AWARD ...........................................................................177 V. EXPLAINING THE AWARD ........................................................178 * Henry D. Fetter is the author of TAKING ON THE YANKEES: WINNING AND LOSING IN THE BUSINESS OF BASEBALL (2005). His writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Times Literary Supplement, The Public Interest, New York History, and the Journal of Sport History and he blogs about the politics and business of sports for theatlantic.com. He is a graduate of Harvard Law School and also holds degrees in history from Harvard College and the University of California, Berkeley. He is a member of the California and New York bars and has practiced business and entertainment litigation in Los Angeles for the past thirty years. Research for this article was funded in part by a Yoseloff-SABR Research Grant from the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). I wish to thank Albany Government Law Review for the opportunity to participate in the “Baseball and the Law” symposium and Bennett Liebman, my East Meadow High School classmate, the then-executive director of the Albany Law School Government Law Center, for initiating the invitation to appear. 156 2012] FROM FLOOD TO FREE AGENCY 157 INTRODUCTION On December 23, 1975, a three-member arbitration panel chaired, by neutral arbitrator Peter Seitz, ruled by a two-to-one vote that Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith and Baltimore Orioles pitcher Dave McNally were “free agents” who could negotiate with any major league club for their future services. -

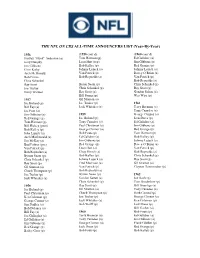

THE NFL on CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year)

THE NFL ON CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year) 1956 (1958 cont’d) (1960 cont’d) Hartley “Hunk” Anderson (a) Tom Harmon (p) Ed Gallaher (a) Jerry Dunphy Leon Hart (rep) Jim Gibbons (p) Jim Gibbons Bob Kelley (p) Red Grange (p) Gene Kirby Johnny Lujack (a) Johnny Lujack (a) Arch McDonald Van Patrick (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Bob Prince Bob Reynolds (a) Van Patrick (p) Chris Schenkel Bob Reynolds (a) Ray Scott Byron Saam (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Joe Tucker Chris Schenkel (p) Ray Scott (p) Harry Wismer Ray Scott (p) Gordon Soltau (a) Bill Symes (p) Wes Wise (p) 1957 Gil Stratton (a) Joe Boland (p) Joe Tucker (p) 1961 Bill Fay (a) Jack Whitaker (p) Terry Brennan (a) Joe Foss (a) Tony Canadeo (a) Jim Gibbons (p) 1959 George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) Joe Boland (p) Jack Drees (p) Tom Harmon (p) Tony Canadeo (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bill Hickey (post) Paul Christman (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Bob Kelley (p) George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) John Lujack (a) Bob Fouts (p) Tom Harmon (p) Arch MacDonald (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bob Kelley (p) Jim McKay (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Bud Palmer (pre) Red Grange (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Van Patrick (p) Leon Hart (a) Van Patrick (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Elroy Hirsch (a) Bob Reynolds (a) Byrum Saam (p) Bob Kelley (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Ray Scott (p) Ray Scott (p) Fred Morrison (a) Gil Stratton (a) Gil Stratton (a) Van Patrick (p) Clayton Tonnemaker (p) Chuck Thompson (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Joe Tucker (p) Byrum Saam (p) 1962 Jack Whitaker (a) Gordon Saltau (a) Joe Bach (p) Chris Schenkel -

Television (Non-ESPN)

Television (non-ESPN) Allen, Maury. “White On! Bill [White] Breaks Color Line in [Baseball] Broadcast Booth. New York Post, 5 February 2006, as reprinted from the New York Post, 10 February, 1971, https://nypost.com/2006/02/05/white-on-bill-breaks-color-line-in-baseball- booth/ “Another NBC [Olympic] Host Apology [,This Time For Comment About Dutch].” New York Post, 14 February 2018, 56-57. Associated Press. “Voice of Yankees Remembered [as Former Athletes Gather for Mel Allen’s Funeral].” New York Post, 20 June 1996, 70. Associated Press. “Ken Coleman, 78, Red Sox Broadcaster[, Dies].” New York Times, 23 August 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/23/sports/ken-coleman-78-red-sox- broadcaster.html Associated Press. “[Hope] Solo Won’t Be Punished for Her Twitter Rant [Criticizing Brandi Chastain’s Commentary During NBC Women’s Soccer Broadcast].” New York Post, 30 July 2012, 64. Atkinson, Claire. “Stars Blow ‘Whistle’ for Kids Media Outlet [Dedicated to Sports. Start-Up Will Feature Digital Tie-Ins and Programming Block on NBC Sports Network].” New York Post, 5 July 2012, 31. Atkinson, Claire. “Taking on ESPN: FOX Sports Kicking off National Cable Network in Aug.” New York Post, 6 March 2013, 31. Atkinson, Claire. “Fat City for Stats Sports Data Service [That] Could Fetch $200M. [Service Is Used by FOX and Other TV Networks].” New York Post, 27 November 2013, 32. Barber, Red. The Broadcasters. New York: Dial Press, 1970. Barber, Red, and Robert W. Creamer. Rhubarb in the Catbird Seat. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. Barnett, Steven. Games and Sets: The Changing Face of Sport on Television. -

Angell, Roger

Master Bibliography (1,000+ Entries) Aamidor, Abe. “Sports: Have We Lost Control of Our Content [to Sports Leagues That Insist on Holding Copyright]?” Quill 89, no. 4 (2001): 16-20. Aamidor, Abraham, ed. Real Sports Reporting. Bloomington, Ind.: University of Indiana Press, 2003. Absher, Frank. “[Baseball on Radio in St. Louis] Before Buck.” St. Louis Journalism Review 30, no. 220 (1999): 1-2. Absher, Frank. “Play-by-Play from Station to Station [and the History of Baseball on Midwest Radio].” St. Louis Journalism Review 35, no. 275 (2005): 14-15. Ackert, Kristie. “Devils Radio Analyst and Former Daily News Sportswriter Sherry Ross Due [New Jersey State] Honor for Historic Broadcast [After Becoming First Woman to Do Play-by-Play of a Full NHL Game in English].” Daily News (New York), 16 March 2010, http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/hockey/devils-radio-analyst-daily- news-sportswriter-sherry-ross-due-honor-historic-broadcast-article-1.176580 Ackert, Kristie. “No More ‘Baby’ Talk. [Column Reflects on Writer’s Encounters with Sexual Harassment Amid ESPN Analyst Ron Franklin Calling Sideline Reporter Jeannine Edwards ‘Sweet Baby’].” Daily News (New York), 9 January 2011, 60. Adams, Terry, and Charles A. Tuggle. “ESPN’s SportsCenter and Coverage of Women’s Athletics: ‘It’s a Boy’s Club.’” Mass Communication & Society 7, no. 2 (2004): 237- 248. Airne, David J. “Silent Sexuality: An Examination of the Role(s) Fans Play in Hiding Athletes’ Sexuality.” Paper presented at the annual conference of the National Communication Association, Chicago, November 2007. Allen, Maury. “White On! Bill [White] Breaks Color Line in [Baseball] Broadcast Booth. -

Grosse Pointe News 1990

Residents make the news zn• the Pointes • By Ronald J Bernas zn 1990 Staff Wnter Shores council could revIse Its master plan board named Edward Shine, former deputy After many more tWlbts and turns, the whIch wal'> last updated 1111956. The pailt yedr could be called the yenr of buperlntendent, to fill Whl'ltner's spot "tory wlll end, for good 01' fOl bad, on Feb 4 The Groil..,e POll1te War Memonal Assocla. grasb rootil Heilldent concems and com- In other school news, the board decIded to - the date set by the board for a bond Issue tlOn announced plans to build a new cable plamts cauiled boardil and city counclls to abk the people of the Pomte.., to fund a pro_ electIOn ..,tudlO on the groundil of the War Memonal re thll1k theIr actlOnil and bow to the wlll of posed $7 1 mllhon hbrary on the !,'1'ounds of The cIty of Detroit began repldcmg the The Glosse POinte Farmb councIl approved the people A ilhOl t I ecap of the year's Brownell Middle School The lIbrary and Its bndge <;pannmg Fox Creek The new bndge eventi> follow., It, then resIdents started complaining ups and downs were a ,>tory that dommated clo..,ed Wmdmlll POinte Dnve at Alter Hoad PACE -- the Program for AcademIc and the news all year January Cleatlve EducatlOn - was to be gIven a The plan called for a new lIbrary, and for February one year overhaul, because then-Supel'ln. the administratIOn to move Its ofIices to the [t stal ted off with a freeze - on new con tendent John Whntner said It wasn't work- current Central Library, and then for the The schoo,,", once d~am took -

Sunday, May 18, 1980 St.John's University New York

SUNDAY, MAY 18, 1980 ST.JOHN'S UNIVERSITY NEW YORK St. John's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences School of Education and Human Services College of Business Administration Callege of Pharmacy and Allied Health Professions St. Vincent's Callege BACCALAUREATE MASS SUNDAY, MAY 18, 1980 DEDICATION OF ST. JOHN'S UNIVERSITY TO MARY IMMACULATE PRINCIPAL CELEBRANT Mary, Mother of God, Holy Virgin, we, the Board of Trustees, administrators, VERY REVEREND JOSEPH T. CAHILL, C.M. faculty, and students of St. John's University, renew our filial and abiding love to you President at this Baccalaureate Mass, as we consecrate again our beloved University to you. With CON CELEBRANTS you, may we be consecrated completely to our Son, Christ our Lord, and like you, REVEREND JOHN V. NEWMAN, C.M. dedicated to fulfilling the will of Our Father. Our intentions in this dedication Special Assistant to the President and Vice President for include our whole being-all that we have, all that we presently are, and especially all Alumni Affairs and Auxiliary Services REVEREND THOMAS P. MALLAGHAN, C.M. that we ever hope to be. In our re-consecration, we ask you to reserve a special place in Assistant to the President your maternal heart for our benefactors, relatives and fri ends, without whose prayers REVEREND JOSEPH I. DIRVIN, C.M. and material assistance our noble commitments are impossible. Humbly we Vice President for University Relations and Secretary acknowledge how profoundly and earnestly we depend upon yo ur continued REVEREND THOMAS V. CONCAGH, C.M. intercession in the realization of the sublime objectives of our University. -

Foundation Funds a Facelift at Farms Park

___ 4__ - ,.......,. __.. ~_....F ~ .. ~-............-- .... ~----- Section rosse Pointe ews A -------------- .- P"bU.".d a. Su ... d CI... 101""., "I ,to. 3De 'er Copy 30 Pages-Two Sections VOL. 42-NO. 52 , •• 1 Offi.e 01 D.I •• il, Mi.hi .... GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1981 $13 'er V.a, --- ------ -----~------- Foundation funds a facelift at Farms park By Tom Greenwood "We are enlisting private help for public good," said Marco. "Residents will be invited to become members The Farms Pier Park will un- of the Foundation and to subscribe dergo a $750,OCO face lift be- to its efforts on an annual basis, ginning in the fall of 1982, ac- We've already approached a few in. cording to members of the dividuals in lhe Farms and have been Grosse Pointe Farms Founda- vcry gratified by the response. Every- tion. one really seems in favor of the proj- ect" Scheduled to be accomplished in two planned phases, the first step will TYPES OF memberships in the include the construction of a new Foundation include: annual~$lO; an, two.story, brick and rough cut cedar nual charter - $50; Major Donor - boathouse to replace the present , $1,000; Life Donor-$5.000 and Life structure which was erected some- Palron-$10,OOO. time after World War 1. Marco added that the Foundation Projected cost of the new boat- has in mind a number of other proj. house is in the $450.000 to $500.000 ec"ts through the city, all of them de. range, Other first phase improve- signed to enhance the esthetic and ments include a re-arrangement of recreational qualities of the Farms, the entrance off Lakeshore Road, a new gate house and extensive land. -

TOTAL SPORTSCASTING This Page Intentionally Left Blank TOTAL SPORTSCASTING PERFORMANCE, PRODUCTION, and CAREER DEVELOPMENT

TOTAL SPORTSCASTING This page intentionally left blank TOTAL SPORTSCASTING PERFORMANCE, PRODUCTION, AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT Marc Zumoff and Max Negin First published 2015 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2015 Taylor & Francis The right of Marc Zumoff & Max Negin to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notices Knowledge and best practice in this fi eld are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zumoff, Marc.