Modernizing US Marine Corps Human Capital Investment and Retention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. __________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States LAWRENCE G. HUTCHINS III, SERGEANT, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI S. BABU KAZA CHRIS G. OPRISON LtCol, USMCR DLA Piper LLP (US) THOMAS R. FRICTON 500 8th St, NW Captain, USMC Washington DC Counsel of Record Civilian Counsel for U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Petitioner Appellate Defense Division 202-664-6543 1254 Charles Morris St, SE Washington Navy Yard, D.C. 20374 202-685-7291 [email protected] i QUESTION PRESENTED In Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970), this Court held that the collateral estoppel aspect of the Double Jeopardy Clause bars a prosecution that depends on a fact necessarily decided in the defendant’s favor by an earlier acquittal. Here, the Petitioner, Sergeant Hutchins, successfully fought war crime charges at his first trial which alleged that he had conspired with his subordinate Marines to commit a killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim. The members panel (jury) specifically found Sergeant Hutchins not guilty of that aspect of the conspiracy charge, and of the corresponding overt acts and substantive offenses. The panel instead found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the lesser-included offense of conspiring to commit an unlawful killing of a named suspected insurgent leader, and found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the substantive crimes in furtherance of that specific conspiracy. After those convictions were later reversed, Sergeant Hutchins was taken to a second trial in 2015 where the Government once again alleged that the charged conspiracy agreement was for the killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim, and presented evidence of the overt acts and criminal offenses for which Sergeant Hutchins had previously been acquitted. -

Joint Force Quarterly, Issue

Issue 100, 1st Quarter 2021 Countering Chinese Coercion Remotely Piloted Airstrikes Logistics Under Fire JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY ISSUE ONE HUNDRED, 1 ST QUARTER 2021 Joint Force Quarterly Founded in 1993 • Vol. 100, 1st Quarter 2021 https://ndupress.ndu.edu GEN Mark A. Milley, USA, Publisher VADM Frederick J. Roegge, USN, President, NDU Editor in Chief Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Senior Editor and Director of Art John J. Church, D.M.A. Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Copyeditor Andrea L. Connell Book Review Editor Brett Swaney Creative Director Marco Marchegiani, U.S. Government Publishing Office Advisory Committee BrigGen Jay M. Bargeron, USMC/Marine Corps War College; RDML Shoshana S. Chatfield, USN/U.S. Naval War College; BG Joy L. Curriera, USA/Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy; Col Lee G. Gentile, Jr., USAF/Air Command and Staff College; Col Thomas J. Gordon, USMC/Marine Corps Command and Staff College; Ambassador John Hoover/College of International Security Affairs; Cassandra C. Lewis, Ph.D./College of Information and Cyberspace; LTG Michael D. Lundy, USA/U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; MG Stephen J. Maranian, USA/U.S. Army War College; VADM Stuart B. Munsch, USN/The Joint Staff; LTG Andrew P. Poppas, USA/The Joint Staff; RDML Cedric E. Pringle, USN/National War College; Brig Gen Michael T. Rawls, USAF/Air War College; MajGen W.H. Seely III/Joint Forces Staff College Editorial Board Richard K. Betts/Columbia University; Eliot A. Cohen/The Johns Hopkins University; Richard L. -

Evolving Theory for Cyberspace

I ssue 73, 2nd Quarter 2014 JOINT FORCE QUARTERL Y E volving Theory I SSUE for Cyberspace S EVENTY-THREE, 2 EVENTY-THREE, Educating Future Strategic Leaders ND Next Steps QUARTER 2014 in Targeting Joint Force Quarterly Founded in 1993 • Vol. 73, 2nd Quarter 2014 http://ndupress.ndu.edu GEN Martin E. Dempsey, USA, Publisher MG Gregg F. Martin, USA, President, NDU Editor in Chief Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Production Editor John J. Church, D.M.A. Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Photography Editor Martin J. Peters, Jr. Senior Copy Editor Calvin B. Kelley Art Director Marco Marchegiani, U.S. Government Printing Office Advisory Committee BG Guy T. Cosentino, USA/National War College; MG Anthony A. Cucolo III, USA/U.S. Army War College; Brig Gen Thomas H. Deale, USAF/Air Command and Staff College; Col Mark J. Desens, USMC/Marine Corps Command and Staff College; Lt Gen David L. Goldfein, USAF/The Joint Staff; BGen Thomas A. Gorry, USMC/ Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy; Maj Gen Scott M. Hanson, USAF/ Air War College; Col Jay L. Hatton, USMC/ Marine Corps War College; LTG David G. Perkins, USA/U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; RDML John W. Smith, Jr., USN/Joint Forces Staff College; LtGen Thomas D. Waldhauser, USMC/The Joint Staff Editorial Board Richard K. Betts/Columbia University; Stephen D. Chiabotti/School of Advanced Air and Space Studies; Eliot A. Cohen/The Johns Hopkins University; COL Joseph J. Collins, USA (Ret.)/National War College; Mark J. -

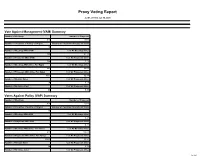

Proxy Voting Report

Proxy Voting Report Jul 01, 2019 to Jun 30, 2020 Vote Against Management (VAM) Summary Number of Meetings Number of Proposals 913 10318 Number of Countries (Country of Origin) Number of Countries (Country of Trade) 15 1 Number of Meetings With VAM % of All Meetings Voted 389 42.7% Number of Proposals With VAM % of All Proposals Voted 736 7.1% Number of Meetings With Votes For Mgmt % of All Meetings Voted 907 99.6% Number of Proposals With Votes For Mgmt % of All Proposals Voted 9551 92.8% Number of Abstain Votes % of All Proposals Voted 74 0.7% Number of No Votes Cast % of All Proposals Voted 23 0.2% Votes Against Policy (VAP) Summary Number of Meetings Number of Proposals 913 10318 Number of Countries (Country of Origin) Number of Countries (Country of Trade) 15 1 Number of Meetings With VAP % of All Meetings Voted 2 0.2% Number of Proposals With VAP % of All Proposals Voted 7 0.1% Number of Meetings With Votes For Policy % of All Meetings Voted 911 100.0% Number of Proposals With Votes For Policy % of All Proposals Voted 10288 99.9% Number of Abstain Votes % of All Proposals Voted 74 0.7% Number of No Votes Cast % of All Proposals Voted 1 of 459 23 0.2% Number of Proposals with Votes with GL % of All Proposals Voted 10166 98.8% Proposal Summary Number of Meetings: 913 Number of Mgmt Proposals: 9914 Number of Shareholder Proposals: 404 Mgmt Proposals Voted FOR % of All Mgmt Proposals ShrHldr Proposal Voted FOR % of All ShrHldr Proposals 9387 94.7% 223 55.2% Mgmt Proposals Voted Against/Withold % of All Mgmt Proposals ShrHldr Proposals -

Every Dollar Counts: Marines Help Local Restaurant Donate Money to Honor Flight

w Fox and November The Company graduates Friday, Jet February 27, 2015 Vol. 50, No. 8 Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, S.C. “TheStream noise you hear is the sound of freedom.” Page 11 Beaufort.Marines.mil 2 3 facebook.com/MCASBeaufort3 twitter.com/MCASBeaufortSC Marines volunteer to fight litter This is your bill New Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps posts Page 4 Pages 5 Page 6 Every dollar counts: Marines help local restaurant donate money to Honor Flight Photos by Pfc. Samantha Torres Marines and their families from Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort volunteered to help remove dollar bills stapled to the walls of a local restaurant, Feb. 21. Thousands of dol- lars were collected, and will be used to send World War II and Vietnam veterans from the Beaufort and Savannah area to visit veteran memorials in Washington, D.C., through the Honor Flight Program. The money raised provides a free trip for the veterans. Marines take care of their own and continue to do so by assisting those who came before. Voluntary Protection Program: Stay safe, be involved Pfc. Samantha Torres gram established by OSHA, to Staff Writers recognize superior performance in the field of health and safety. Marine Corps Air Station Beau- The program promotes workers’ fort strives to improve the overall safety through active and mean- safety of the Air Station by work- ingful employee involvement, ing with the Voluntary Protection and works in conjunction with Program and the Occupational the Marine Corps’ safety manage- Safety and Health Administration. ment systems. The Voluntary Protection Pro- gram is a cross functional pro- SEE VPP, PAGE 6 Reach out, help a Marine or sailor Cpl. -

Freshman Knowledge Packet

Freshman Knowledge Packet NROTC Mission Statement To develop midshipmen mentally, morally, and physically and to imbue them with the highest ideals of honor, duty, and loyalty. To commission college graduates as naval officers who possess a basic professional background, are motivated toward careers in the naval service, and have a potential for future development in mind and character so as to assume the highest responsibilities of command, citizenship, and government. ~ 1 ~ Table of Contents Commanding Officers Guidance pages 3-5 OSUNROTC History page 6 Naval Glossary/Terminology pages 7-8 Goals of NROTC/Chain of Command page 9 National Chain of Command Photographs page 10 Unit and Battalion Staff Defined page 11 Unit Staff Photographs page 12 Battalion Structure page 13 Midshipmen Honor Code/Navy Core Values page 14 Sailors’ Creed/Military Code of Conduct page 15 Marine Eleven General Orders page 16 Navy Knowledge/US National Ensign page 17 USMC Knowledge/Leadership Traits page 18 Anchor’s Away Lyrics page 19 The Marine’s Hymn Lyrics page 20 US Officers Rank and Insignia page 21 US Navy and Marine Corps Enlisted Rank and Insignia page 22 Midshipmen Rank and Insignia page 23 Uniforms/Insignia/Grooming pages 24-31 Academic Standards page 32 NROTC PFA Standards pages 33-36 Cadences/Notes pages 37-38 Campus Map pages 39-40 ~ 2 ~ 20011-2012 Commanding Officer Guidance to The Ohio State University Naval ROTC Battalion There are two key objectives while you are enrolled in the Naval ROTC unit at The Ohio State University. The first is to earn a bachelor‘s degree and the second is to earn a commission in the Navy or Marine Corps. -

Newsletter Editor: Lou Piantadosi

MC-LEF MARINE CORPS-LAW ENFORCEMENT FOUNDATION Educating the children of those who sacrificed all SEPT 2017 N E W S L E T T E R ISSUE #54 22ND ANNUAL NYC GALA 8TH ANNUAL PHILLY GATHERING OF HEROES SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 35 BOSTON MARATHON -TEAM KELLY... SEE PAGE 31 SCHOLARSHIP AWARD ARIZONA GOLF MEMBERS ON THE GO SEE PAGE 7 SEE PAGE 22 SEE PAGE 38 JACK LUCAS STORY ATLANTIC CITY GALA & GOLF FBI SCHOLARSHIPS SEE PAGE 21 SEE PAGE 10 SEE PAGE 34 FOLLOW MC-LEF www.mc-lef.org MARINE CORPS - LAW ENFORCEMENT FOUNDATION 273 Columbus Avenue • Office #10 • Tuckahoe, NY 10707 None of the MC-LEF Directors or Officers receives compensation for their services BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman Emeritus: Zachary Fisher (1910-1999) New York Vice Chairman Emeritus: Steve Wallace (1942-2010 California Chairman: James K. Kallstrom New York Vice Chairman: Gen. Peter Pace, USMC, (Ret.) North Carolina Vice Chairman: Gary Schweikert New York Marine Corps - Law Enforcement Chaplain: Monsignor Robert T. Ritchie New York Foundation DIRECTORS Mr. Sandy Alderson New York Gen. James Amos, USMC (Ret.) North Carolina Westy Ballard Texas Col. Barney Barnum, USMC (Ret.) Virginia OUR MISSION Mr. Anthony Boyle Pennsylvania Christopher Burnham Virginia LtGen. Ron S. Coleman, USMC (Ret.) Virginia The Marine Corps-Law Enforcement Mr. John Conner New York Gen. James T. Conway, 34th CMC, USMC ( Ret) Pennsylvania Foundation (MC-LEF) provides educational David Cornstein New York assistance to the children of fallen United States Mr. Ken Courey Florida Mr. Robert Cummins New York Marines and federal law enforcement personnel. -

Key Officials September 1947–July 2021

Department of Defense Key Officials September 1947–July 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Introduction 1 I. Current Department of Defense Key Officials 2 II. Secretaries of Defense 5 III. Deputy Secretaries of Defense 11 IV. Secretaries of the Military Departments 17 V. Under Secretaries and Deputy Under Secretaries of Defense 28 Research and Engineering .................................................28 Acquisition and Sustainment ..............................................30 Policy ..................................................................34 Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer ........................................37 Personnel and Readiness ..................................................40 Intelligence and Security ..................................................42 VI. Specified Officials 45 Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation ...................................45 General Counsel of the Department of Defense ..............................47 Inspector General of the Department of Defense .............................48 VII. Assistant Secretaries of Defense 50 Acquisition ..............................................................50 Health Affairs ...........................................................50 Homeland Defense and Global Security .....................................52 Indo-Pacific Security Affairs ...............................................53 International Security Affairs ..............................................54 Legislative Affairs ........................................................56 -

THE University of Memphis Naval ROTC MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE

THE University of Memphis Naval ROTC MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE Handbook 2014 (This page intentionally left blank) 1 May 2014 From: Commanding Officer, Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps, Mid-South Region, The University of Memphis To: Incoming Midshipmen Subj: MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK Ref: (a) NSTC M-1533.2 1. PURPOSE: The purpose of this handbook is to provide a funda- mental background of knowledge for all participants in the Naval ROTC program at The University of Memphis. 2. INFORMATION: All chapters in this book contain vital, but basic information that will serve as the building blocks for future development as Naval and Marine Corps Officers. 3. ACTIONS: Midshipmen, Officer Candidates, and Marine Enlisted Commissioning Education Program participants are expected to know and understand all information contained within this handbook. Navy students will know the Marine information, and Marine students will know the Navy information. This will help to foster a sense of pride and esprit de corps that shapes the common bond that is shared amongst the two Naval Services. B. C. MAI (This page intentionally left blank) MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE 1 INTRODUCTION 2 CHAIN OF COMMAND 3 LEADERSHIP 4 GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 5 NAVY SPECIFIC KNOWLEDGE 6 MARINE CORPS SPECIFIC KNOWLEDGE APPENDIX A CHAIN OF COMMAND FILL-IN SHEET B STUDENT COMPANY CHAIN OF COMMAND FILL-IN SHEET C UNITED STATES MILITARY OFFICER RANKS D UNITED STATES MILITARY ENLISTED RANKS FIGURES 2-1 CHAIN OF COMMAND FLOW CHART 2-2 STUDENT COMPANY CHAIN OF COMMAND FLOW CHART 4-1 NAVAL TERMINOLOGY (This page intentionally left blank) MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPH PAGE PURPOSE 1001 1-3 SCOPE 1002 1-3 GUIDELINES 1003 1-3 NROTC PROGRAM MISSION 1004 1-3 1-1 (This page intentionally left blank) MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK 1001: PURPOSE 1. -

Air Force Professional Military Education Considerations for Change for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N LAWRENCE M. HANSER, JENNIFER J. LI, CARRA S. SIMS, NORAH GRIFFIN, SPENCER R. CASE Air Force Professional Military Education Considerations for Change For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA401-1. About RAND The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. To learn more about RAND, visit www.rand.org. Research Integrity Our mission to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis is enabled through our core values of quality and objectivity and our unwavering commitment to the highest level of integrity and ethical behavior. To help ensure our research and analysis are rigorous, objective, and nonpartisan, we subject our research publications to a robust and exacting quality-assurance process; avoid both the appearance and reality of financial and other conflicts of interest through staff training, project screening, and a policy of mandatory disclosure; and pursue transparency in our research engagements through our commitment to the open publication of our research findings and recommendations, disclosure of the source of funding of published research, and policies to ensure intellectual independence. For more information, visit www.rand.org/about/principles. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © 2021 RAND Corporation is a registered trademark. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. -

Read HVLA's Response to the IRDR

The Air Force’s Independent Racial Disparity Review (IRDR) – A Good First Step Introduction As a military- and veteran-led 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, the Hispanic Veterans Leadership Alliance (HVLA) is committed to advancing the inclusion of Hispanics throughout the Department of Defense (DoD). HVLA members represent dozens of former senior leaders from all branches and components of the military. We collectively represent over seven centuries of distinguished military and civilian service in the DoD. In reviewing the Air Force’s IRDR published in December 2020, we determined that the report provides an excellent analysis of the issues facing black service members in the Air Force and serves as a model for a much-needed companion analysis of the issues facing the largest minority ethnic group in the Air Force—Hispanics. In its introduction, the IRDR states: • The DAF recognizes other disparities across a range of minority groups are equally deserving of such a review. However, this Review was intentionally surgically-focused on discipline and opportunity regarding black service members to permit a timely yet thorough review that should lead to systemic and lasting change, as appropriate. Nonetheless, lessons learned and insights gained from this Review should benefit broader minority initiatives. (IRDR, p. 1) We concur wholeheartedly with this assessment and believe that while the IRDR focused on the issues facing black service members, there are sufficient additional data regarding comparable issues facing Hispanics in the IRDR itself to justify an immediate comparable deep-dive on Hispanic issues. This paper summarizes those portions of the IRDR that provide specific information regarding Hispanics that must be further examined like black service member issues have been examined in the IRDR.