Etd Kdj7.Pdf (542Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Leadership

2018 Annual Report RISEON THE LEADERSHIP NATIONAL BOARD OF TRUSTEES James A. Miller Thomas Schumacher Matt Conover, Chair Bartlett Wealth Management, Principal and Disney Theatrical Group, President Chairman Disney Parks Live Entertainment, Cincinnati, OH Vice President of Disneyland Entertainment Deborah Voigt Award-winning opera soprano Anaheim, CA Megan Tulac Phillips Hunter Bell, Vice Chair McKinsey & Company, Head of Marketing and ADVISORY BOARD Communications, Enterprise Agility Tony-nominated playwright, EdTA Board of San Francisco, CA Sarah Jane Arnegger Directors iHeart Radio Broadway, Director New York, NY John Prignano New York, NY Debbie Hill, Secretary Music Theatre International, COO and Director of Education and Development Aretta Baumgartner Community Arts Initiatives, Founder and New York, NY Center for Puppetry Arts, Education Director Executive Director Atlanta, GA Cincinnati, OH Kim Rogers Dori Berinstein Alex Birsh Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Amateur Licensing Dramatic Forces, Producer Playbill, Vice President and Chief Digital Officer New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY J. Jason Daunter Mark Drum David Redman Scott Disney Theatrical Group, Director of Theatrical Production Stage Manager Actor, Arts Advocate, EdTA Volunteer Licensing New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY Debby Gibbs Nancy Aborn Duffy ETF Legacy Circle Committee, Chair Educator, Former Broadway Licensing Abbie Van Nostrand Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Client Tupelo, MS Company Owner Relations & Community Engagement New York, NY -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Motion Picture

Moving Images Prepared by Bobby Bothmann RDA Moving Images by Robert L. Bothmann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Created 2 February 2013 Modified 11 November 2014 https://link.mnsu.edu/rda-video Scope Step-through view of the movie Hairspray from 2007 Generally in RDA rule order Uses MARC 21 examples Describing Manifestations & Items Follows RDA Chapters 2, 3, 4 Describing Works and Expressions Follows RDA Chapters 6, 7 Recording Attributes of Person & Corporate Body Uses RDA Chapters 9, 11, 18 Covers relator terms only Recording Relationships Follows RDA Chapters 24, 25, 26 2 Resources Olson, Nancy B., Robert L. Bothmann, and Jessica J. Schomberg. Cataloging of Audiovisual Materials and Other Special Materials: A Manual Based on AACR2 and MARC 21. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited, 2008. [Short citation: CAVM] Online Audiovisual Catalogers, Inc. Cataloging Policy Committee. Streaming Media Best Practices Task Force. Best Practices for Cataloging Streaming Media. No place : OLAC CAPC, 2009. http://olacinc.org/drupal/capc_files/streamingmedia.pdf Online Audiovisual Catalogers, Inc. Cataloging Policy Committee. DVD Cataloging Guide Update Task Force. Guide to Cataloging DVD and Blu-ray Discs Using AACR2r and MARC 21. 2008 Update. No place: OLAC CAPC, 2008. http://olacinc.org/drupal/capc_files/DVD_guide_final.pdf Pan-Canadian Working Group on Cataloguing with RDA. “Workflow: Video recording (DVD) RDA.” In RDA Toolkit | Tools| Workflows |Global Workflows. 3 Preferred Source 4 5 Title Proper 2.3.2.1 RDA CORE the chief name of a resource (i.e., the title normally used when citing the resource). 245 10 $a Hairspray Capitalization is institutional and cataloger’s choice Describing Manifestations 6 Note on the Title Proper 2.17.2.3 RDA Make a note on the source from which the title proper is taken if it is a source other than: a) the title page, .. -

Woody & Linda Brownlee 190 @ Jupiter Office

The Garland Summer Musicals in partnership with RICHLAND COLLEGE proudly presents Woody & Linda Brownlee 190 @ Jupiter Office Granville Arts Center Garland, Texas Office Location: June 17-26, 2011 3621 Shire Blvd. Ste. 100 Richardson, Texas 75082 Presented through special grants from GARLAND CULTURAL ARTS COMMISSION, INC. 214-808-1008 Cell Linda GARLAND SUMMER MUSICALS GUILD 972-989-9550 Cell Woody GARLAND POWER & LIGHT [email protected] ALICE & GORDON STONE [email protected] ECOLAB, INC. www.brownleeteam.ebby.com MICROPAC INDUSTRIES Garland Summer Musicals Presents Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Broadway Blockbuster CATS! July 22, 23, 29, 30 at 8pm July 24, 31 at 2:30pm Tickets: $27 - Adults; $25 - Seniors/Students; $22 - Youth Special discounts for season tickets, corporate sales and groups GRANVILLE ARTS CENTER - 300 N. Fifth Street, Garland, Texas 75040 Call the Box Office at 972-205-2790 The Garland Summer Musicals Guild presents Dallas' most famous entertainment group The Levee Singers Saturday, September 24, 2011 Plaza Theatre 521 W. State Street—Garland, TX The Levee Singers are celebrating their 50th anniversary this year and are busier and better than ever! Come join the GSM Guild as they present this spectacular fun-filled evening with the Levee Singers. For tickets call 972-205-2790. THE GARLAND SUMMER MUSICALS SPECIAL THANKS Presents MEREDITH WILLSON’S GARLAND SUMMER MUSICALS GUILD “The Music Man” SACHSE HIGH SCHOOL—Joe Murdock and Libby Nelson Starring THE SACHSE HIGH SCHOOL TECHNICAL CLASS STAN GRANER JACQUELYN LENGFELDER NAAMAN FOREST HIGH SCHOOL BAND—Larry Schnitzer Featuring NORTH GARLAND HIGH SCHOOL—Mikey Abrams & Nancy Gibson JAMES WILLIAMS MELISSA TUCKER J.J. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

The Pajama Game at the 5Th Avenue Theatre Encore Arts Seattle

THE NATION’S LEADING MUSICAL THEATER FEB 10-MAR 5, 2017 FEBRUARY 2017 My wealth. My priorities. My partner. You’ve spent your life accumulating wealth. And, no doubt, that wealth now takes many forms, sits in many places, and is managed by many advisors. Unfortunately, that kind of fragmentation creates gaps that can hold your wealth back from its full potential. The Private Bank can help. The Private Bank uses a proprietary approach called the LIFE Wealth Cycle SM to ind those gaps—and help you achieve what is important to you. To learn more, contact: Carolyn Stewart Vice President, Private Wealth Advisor 2065874788 [email protected] or visit unionbank.com/theprivatebank Wills, trusts, foundations, and wealth planning strategies have legal, tax, accounting, and other implications. Clients should consult a legal or tax advisor. ©2016 MUFG Union Bank, N.A. All rights reserved. Member FDIC. Union Bank is a registered trademark and brand name of MUFG Union Bank, N.A. EAP full-page template.indd 1 9/6/16 11:17 AM February 2017 Volume 14, No. 4 cinema Paul Heppner Publisher Susan Peterson Design & Production Director Ana Alvira, Robin Kessler, Shaun Swick, Stevie VanBronkhorst Production Artists and Graphic Design Mike Hathaway Sales Director Brieanna Bright, Joey Chapman, Ann Manning, Rob Scott Seattle Area Account Executives Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives Jonathan Shipley Ad Services Coordinator Carol Yip Sales Coordinator Sara Keats Jonathan Shipley Online Editors NT LIVE: HEDDA GABLER STARRING RUTH WILSON (“LUTHER,” “THE AFFAIR”) THU, MAR. 9 • 11AM & 6:30PM • SIFF CINEMA UPTOWN Leah Baltus Editor-in-Chief FOR TICKETS VISIT SIFF.NET/HEDDAGABLER Paul Heppner Publisher Dan Paulus Art Director Gemma Wilson, Jonathan Zwickel Senior Editors Amanda Manitach Visual Arts Editor Barry Johnson Associate Digital Editor Make retirement Paul Heppner delicious. -

The Pajama Game

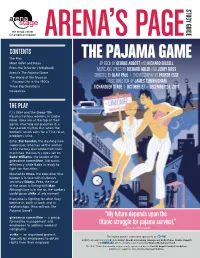

ARENA’S PAGE STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS The Play THE PAJAMA GAME Meet Adler and Ross BY BOOK BY GEORGE ABBOTT AND RICHARD BISSELL From the Director’s Notebook MUSIC AND LYRICS BY RICHARD ADLER AND JERRY ROSS Arena’s The Pajama Game The World of the Musical: DIRECTED BY ALAN PAUL | CHOREOGRAPHY BY PARKER ESSE Factory Life in the 1900s MUSIC DIRECTION BY JAMES CUNNINGHAM Three Big Questions FICHANDLER STAGE | OCTOBER 27 — DECEMBER 24, 2017 Resources THE PLAY It is 1954 and the Sleep-Tite Pajama Factory workers in Cedar Rose, Iowa are at the top of their game, churning out pajamas in a fast-paced rhythm. But when the workers’ union asks for a 7 1/2¢ raise, problems arise. Enter Sid Sorokin, the dashing new supervisor, who has all the women in the factory distracted from their machines. He has his eyes set on Babe Williams, the leader of the grievance committee. Sid wants efficiency while Babe is ready to fight for that raise. Meanwhile Hines, the executive time keeper is in love with his boss’s secretary Gladys. Prez, the head of the union is flirting with Mae. Although love is in the air, the workers could go on strike at any moment. Everyone is fighting for what they believe in, both at work and in relationships. Who will win The Pajama Game? “My future depends upon the grievance committee — a group formed by management and employees to address workers’ titanic struggle for pajama survival.” complaints — Sid, The Pajama Game strike — an organized protest, The Pajama Game is generously sponsored by . -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

Putting It Together

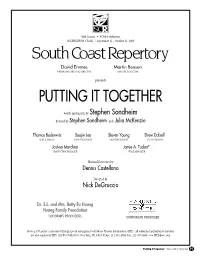

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

• September 29, 2003 Q1

www.ExpressGayNews.com • September 29, 2003 Q1 Q_COVERstory All in the Gay Family ‘It’s All Relative’ Breaks the Next TV Barrier—Gays as Parents By Christopher Lisotta explains. “We wanted the characters to be writing sitcoms you have to stick to basic they are just the unknown,” Harris says of Special to The Express more real.” themes in order to get your story across. her character’s reaction to Philip and Simon For the past few years, Will Truman and Zadan and Meron kept meeting potential “We really think there’s an upside to that, and their long-term relationship. “It’s so not Jack McFarland have been the cutting edge writers before sitting down with Chuck and we can use it to our advantage,” Ranberg a part of her world. She’s got a great life, when it comes to gay sensibility on Ranberg and Anne Flett-Giordano, writing says of the fabulous gay male stereotype. loves her family and just never thought about television. No longer psycho killers or tragic partners who spent several seasons on “Particularly in a comedy, it helps you to start it.” victims, Will & Grace proved that gay Frasier and other well-received sitcoms. out at least with characters who are clearly Harris, who won a Tony for Thoroughly characters could be the central figures on a Although Zadan is quick to point out It’s All recognized archetypes.” Modern Millie and is known to TV audiences well-regarded and, more importantly for the Relative is its own show, the sensibility Christopher Sieber, who plays Simon, as Frasier’s hardcore agent Bebe, sees a networks, profitable situation comedy Ranberg and Flett-Giordano showed on notes that there is plenty to delineate this gay difference between the gaggle of gay-themed without bringing about widespread criticism Frasier struck them as the perfect fit for couple in terms of character. -

University International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Program Notes by Joshua Ritter

PROGRAM NOTES BY JOSHUA RITTER In the late 1960s, political, “Jimmy” and the title song. Many other aspects of the stage social, and artistic change production similarly diverged from the film version. was sweeping across the nation. Virtually everything Universal Pictures released the film at a time when racism was in flux, including was more institutionalized, accepted, and apparent in popular interest in movie peoples’ daily lives. The film reflected this reality. There musicals. When the film was trepidation among the creative team about taking Thoroughly Modern Millie on a project that could offend modern audiences. In fact, was released in 1967, Mayer was not willing to commit to the project unless he director George Roy Hill, could portray the Asian characters in culturally appropriate producer Ross Hunter, and ways. Mayer’s solution was to make the Chinese henchmen screenwriter Richard Morris fully-realized characters that are central to the plot and were inspired by pastiche to have them speak Chinese. He later chose to embrace musicals (e.g., The Boy actress Harriet Harris’ extreme portrayal of an Asian Friend) that were gaining stereotype when she first played Mrs. Meers. The creative popularity in London at the team realized that the opportunity to juxtapose an over- time. In the waning days the-top Asian stereotype with authentic Asian characters of the Hollywood musical, would delegitimize the offensive characterization of Asian Millie spoofed silent films Americans. This daring theatrical choice worked and helped from the 1920s and embraced the farcical slapstick style of propel the show to greater acclaim. this bygone age.