The Disappearing L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alshire Records Discography

Alshire Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Alshire International Records Discography Alshire was located at P.O. Box 7107, Burbank, CA 91505 (Street address: 2818 West Pico Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90006). Founded by Al Sherman in 1964, who bought the Somerset catalog from Dick L. Miller. Arlen, Grit and Oscar were subsidiaries. Alshire was a grocery store rack budget label whose main staple was the “101 Strings Orchestra,” which was several different orchestras over the years, more of a franchise than a single organization. Alshire M/S 3000 Series: M/S 3001 –“Oh Yeah!” A Polka Party – Coal Diggers with Happy Tony [1967] Reissue of Somerset SF 30100. Oh Yeah!/Don't Throw Beer Bottles At The Band/Yak To Na Wojence (Fortunes Of War)/Piwo Polka (Beer Polka)/Wanda And Stash/Moja Marish (My Mary)/Zosia (Sophie)/Ragman Polka/From Ungvara/Disc Jocky Polka/Nie Puki Jashiu (Don't Knock Johnny) Alshire M/ST 5000 Series M/ST 5000 - Stephen Foster - 101 Strings [1964] Beautiful Dreamer/Camptown Races/Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair/Oh Susanna/Old Folks At Home/Steamboat 'Round The Bend/My Old Kentucky Home/Ring Ring De Bango/Come, Where My Love Lies Dreaming/Tribute To Foster Medley/Old Black Joe M/ST 5001 - Victor Herbert - 101 Strings [1964] Ah! Sweet Mystery Of Life/Kiss Me Again/March Of The Toys, Toyland/Indian Summer/Gypsy Love Song/Red Mill Overture/Because You're You/Moonbeams/Every Day Is Ladies' Day To Me/In Old New York/Isle Of Our Dreams M/S 5002 - John Philip Sousa, George M. -

1 GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought TIMES to BE CONFIRMED

GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought TIMES TO BE CONFIRMED: provisionally, Tuesday 1:30-2:45, Thursday TBC Fall Semester 2020 Professor Katrina Forrester Office Hours: TBC E-mail: [email protected] Teaching Fellows: Celia Eckert, Soren Dudley, Kierstan Carter, Eve O’Connor Course Description: What is feminism? What is patriarchy? What and who is a woman? How does gender relate to sexuality, and to class and race? Should housework be waged, should sex be for sale, and should feminists trust the state? This course is an introduction to feminist political thought since the mid-twentieth century. It introduces students to classic texts of late twentieth-century feminism, explores the key arguments that have preoccupied radical, socialist, liberal, Black, postcolonial and queer feminists, examines how these arguments have changed over time, and asks how debates about equality, work, and identity matter today. We will proceed chronologically, reading texts mostly written during feminism’s so-called ‘second wave’, by a range of influential thinkers including Simone de Beauvoir, Shulamith Firestone, bell hooks and Catharine MacKinnon. We will examine how feminists theorized patriarchy, capitalism, labor, property and the state; the relationship of claims of sex, gender, race, and class; the development of contemporary ideas about sexuality, identity, and gender; and how and whether these ideas change how fundamental problems in political theory are understood. 1 Course Requirements: Undergraduate students: 1. Participation (25%): a. Class Participation (15%) Class Participation is an essential part of making a section work. Participation means more than just attendance. You are expected to come to each class ready to discuss the assigned material. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Remarks by Redstockings Speaker Marisa Figueiredo Shulamith Firestone Memorial September 23, 2012

Remarks by Redstockings speaker Marisa Figueiredo Shulamith Firestone Memorial September 23, 2012 In 1978, at the age of 16, while In high school, I lived in Akron, Ohio. I went to to the public library on weekends and on one shelf were three books in a row that changed my life forever and are the reason I am here today: Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex, Shulamith Firestone's The Dialectic of Sex The Case for Feminist Revolution, and Redstockings' Feminist Revolution. With my consciousness raised to the point of passionately identifying myself as a radical feminist in the tradition each book represented, I ardently wanted to connect with Shulamith Firestone and Redstockings , so I wrote to both. I heard back from Redstockings, not Shulamith, and since 1984, I have been active in Redstockings. On May Day in 1986, Redstockings organized a Memorial for Simone de Beauvoir and I felt deeply honored when asked by Kathie Sarachild to read Shulamith's Firestone's tribute she had sent to the Memorial. It was several sentences in Shulamith's beautiful handwriting saying that Simone de Beauvoir had fired her youthful ambitions at age 16 and my heart was pounding as I read it, because Shulamith had fired my youthful ambitions at age 16, too! In the early 1990s, Kathie Sarachild introduced me to Shulamith Firestone, and I remember immediately feeling Shulamith's intensity of observation and perception of details unnoticed by others. All this despite her physical vulnerability that overwhelmed me, which I soon learned from her, resulted from side effects of her medication and a recent hospitalization. -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Sinister Wisdom 70.Pdf

Sinister Sinister Wisdom 70 Wisdom 70 30th Anniversary Celebration Spring 2007 $6$6 US US Publisher: Sinister Wisdom, Inc. Sinister Wisdom 70 Spring 2007 Submission Guidelines Editor: Fran Day Layout and Design: Kim P. Fusch Submissions: See page 152. Check our website at Production Assistant: Jan Shade www.sinisterwisdom.org for updates on upcoming issues. Please read the Board of Directors: Judith K. Witherow, Rose Provenzano, Joan Nestle, submission guidelines below before sending material. Susan Levinkind, Fran Day, Shaba Barnes. Submissions should be sent to the editor or guest editor of the issue. Every- Coordinator: Susan Levinkind thing else should be sent to Sinister Wisdom, POB 3252, Berkeley, CA 94703. Proofreaders: Fran Day and Sandy Tate. Web Design: Sue Lenaerts Submission Guidelines: Please read carefully. Mailing Crew for #68/69: Linda Bacci, Fran Day, Roxanna Fiamma, Submission may be in any style or form, or combination of forms. Casey Fisher, Susan Levinkind, Moire Martin, Stacee Shade, and Maximum submission: five poems, two short stories or essays, or one Sandy Tate. longer piece of up to 2500 words. We prefer that you send your work by Special thanks to: Roxanna Fiamma, Rose Provenzano, Chris Roerden, email in Word. If sent by mail, submissions must be mailed flat (not folded) Jan Shade and Jean Sirius. with your name and address on each page. We prefer you type your work Front Cover Art: “Sinister Wisdom” Photo by Tee A. Corinne (From but short legible handwritten pieces will be considered; tapes accepted the cover of Sinister Wisdom #3, 1977.) from print-impaired women. All work must be on white paper. -

"Rip Her to Shreds": Women's Musk According to a Butch-Femme Aesthetic

"Rip Her to Shreds": Women's Musk According to a Butch-Femme Aesthetic Judith A, Peraino "Rip Her to Shreds" is the tide of a song recorded in 1977 by the rock group Blondie; a song in which the female singer cat tily criticizes another woman. It begins with the female "speak er" addressing other members of her clique by calling attention to a woman who obviously stands outside the group. The lis tener likewise becomes a member of the clique, forced to par ticipate tacitly in the act of criticism. Every stanza of merciless defamation is articulated by a group of voices who shout a cho rus of agreement, enticing the listener to join the fray. (spoken! Hey, psf pst, here she comes !lOW. Ah, you know her, would YOIl look ollhlll hair, Yah, YOIl know her, check out Ihose shoes, A version of this paper was read at the conference "Feminist Theory and Music: Toward a Common Language," Minneapolis, MN, June 1991. If) 20 Peraino Rip Her to Shreds She looked like she stepped out in the middle of somebody's cruise. She looks like the Su nday comics, She thinks she's Brenda Starr, Her nose·job is real atomic, All she needs is an old knife scar. CHORUS: (group) 00, she's so dull, (solo) come on rip her to shreds, (group) She's so dull, (solo) come on rip her to shreds.! In contrast to the backstabbing female which the Blondie song presents, so-called "women's music" emphasizes solidarity and affection between women, and reserves its critical barbs for men and patriarchal society. -

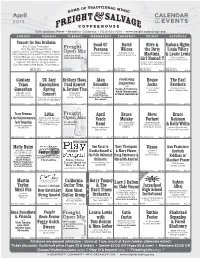

April CALENDAR of EVENTS

April CALENDAR 2013 OF EVENTS 2020 Addison Street • Berkeley, California • (510) 644-2020 • www.freightandsalvage.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Concert for Sue Draheim eric & Suzy Thompson, Good Ol’ David Olive & Barbara Higbie, Jody Stecher & kate brislin, Freight laurie lewis & Tom rozum, kathy kallick, Persons Wilcox the Dirty Linda Tillery Open Mic California bluegrass the best of pop Gerry Tenney & the Hard Times orchestra, pay your dues, trailblazers’ reunion and folk aesthetics Martinis, & Laurie Lewis Golden bough, live oak Ceili band with play and shmooze Hills to Hollers the Patricia kennelly irish step dancers, Girl Named T album release show Tempest, Will Spires, Johnny Harper, rock ‘n’ roots fundraiser don burnham & the bolos, Tony marcus for the rex Foundation $28.50 adv/ $4.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $24.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $22.50 adv/ $30.50 door monday, April 1 $6.50 door Apr 2 $22.50 door Apr 3 $26.50 door Apr 4 $22.50 door Apr 5 $24.50 door Apr 6 Gautam UC Jazz Brittany Haas, Alan Celebrating House The Earl Songwriters Tejas Ensembles Paul Kowert Senauke with Jacks Brothers Zen folk musician, Caren Armstrong, “the rock band Outlaw Hillbilly Ganeshan Spring & Jordan Tice featuring Keith Greeninger without album release show Carnatic music string fever Jon Sholle, instruments” with distinction Concert from three Chad Manning, & Steve Meckfessel and inimitable style featuring the Advanced young virtuosos Suzy & Eric Thompson, Combos and big band Kate Brislin $20.50/$22.50 Apr 7 $14.50/$16.50 Apr -

The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts Presents Two Performances Perfect for the Whole Family!

April 14, 2010 The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts presents two performances perfect for the whole family! LA-based drum, music and dance ensemble STREET BEAT combines urban rhythms, hip-hop moves and break dance acrobatics into an explosive, high-energy performance Grammy ® nominated vocal ensemble Linda Tillery & the Cultural Heritage Choir share the rich traditions of African American Roots music (Philadelphia, April 14, 2010) — The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts presents not one but two performances perfect for the whole family. First, the high-energy, LA-based drum, music and dance ensemble STREET BEAT combine urban rhythms, hip-hop moves and break dance acrobatics into one explosive performance on Thursday, April 29, 2010 at 7:30 PM at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. Tickets for the performance start at just $10. On Friday, April 30, 2010 at 8:00 PM, Linda Tillery & The Cultural Heritage Choir, a Grammy® nominated, five member-strong a cappella ensemble embark on an illuminating and highly spirited journey of African American history. The ensemble’s mission is to help preserve and share the rich musical traditions of African American roots music with a repertoire that runs the gamut from spirituals, gospel, blues, jazz, funk, soul and hip-hop. Tickets for the performance are $25 or $40. For tickets or for more information, please visit AnnenbergCenter.org or call 215.898.3900. Tickets can also be purchased in person at the Annenberg Center Box Office. Both artists are also featured main stage performers during the 26th annual Philadelphia International Children’s Festival taking place at the Annenberg Center April 27-May 1, 2010. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County