Eastern Range Extension of Pseudomys Hermannsburgensis in Queensland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Calaby References

Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents; Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs; Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents; Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents; Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores; Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Mammals of the Avon Region

Mammals of the Avon Region By Mandy Bamford, Rowan Inglis and Katie Watson Foreword by Dr. Tony Friend R N V E M E O N G T E O H F T W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T 1 2 Contents Foreword 6 Introduction 8 Fauna conservation rankings 25 Species name Common name Family Status Page Tachyglossus aculeatus Short-beaked echidna Tachyglossidae not listed 28 Dasyurus geoffroii Chuditch Dasyuridae vulnerable 30 Phascogale calura Red-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae endangered 32 phascogale tapoatafa Brush-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae vulnerable 34 Ningaui yvonnae Southern ningaui Dasyuridae not listed 36 Antechinomys laniger Kultarr Dasyuridae not listed 38 Sminthopsis crassicaudata Fat-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 40 Sminthopsis dolichura Little long-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 42 Sminthopsis gilberti Gilbert’s dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 44 Sminthopsis granulipes White-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 46 Myrmecobius fasciatus Numbat Myrmecobiidae vulnerable 48 Chaeropus ecaudatus Pig-footed bandicoot Peramelinae presumed extinct 50 Isoodon obesulus Quenda Peramelinae priority 5 52 Species name Common name Family Status Page Perameles bougainville Western-barred bandicoot Peramelinae endangered 54 Macrotis lagotis Bilby Peramelinae vulnerable 56 Cercartetus concinnus Western pygmy possum Burramyidae not listed 58 Tarsipes rostratus Honey possum Tarsipedoidea not listed 60 Trichosurus vulpecula Common brushtail possum Phalangeridae not listed 62 Bettongia lesueur Burrowing bettong Potoroidae vulnerable 64 Potorous platyops Broad-faced -

Rodents Bibliography

Calaby’s Rodent Literature Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

An Overdue Break up of the Rodent Genus Pseudomys Into Subgenera As Well As the Formal Naming of Four New Species

30 Australasian Journal of Herpetology Australasian Journal of Herpetology 49:30-41. Published 6 August 2020. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) An overdue break up of the rodent genus Pseudomys into subgenera as well as the formal naming of four new species. LSIDURN:LSID:ZOOBANK.ORG:PUB:627AB9F7-5AD1-4A44-8BBE-E245C4A3A441 RAYMOND T. HOSER LSIDurn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F9D74EB5-CFB5-49A0-8C7C-9F993B8504AE 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 1 May 2020, Accepted 8 July 2020, Published 6 August 2020. ABSTRACT An audit of all previously named species and synonyms within the putative genus of Australian mice Pseudomys (including genera phylogenetically included within Pseudomys in recent studies) found a number of distinctive and divergent species groups. Some of these groups have been treated by past authors as separate genera (e.g. Notomys Lesson, 1842) and others as subgenera (e.g. Thetomys Thomas, 1910). Other groups have been recognized (e.g. as done by Ford 2006), but remain unnamed. This paper assessed the current genus-level classification of all species and assigned them to species groups. Due to the relatively recent radiation and divergence of most species groups being around the five million year mark (Smissen 2017), the appropriate level of division was found to be subgenera. As a result, eleven subgenera are recognized, with five formally named for the first time in accordance with the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Ride et al. 1999). -

Why Are Small Mammals Not Such Good Thermoregulators in Arid

Are day-active small mammals rare and small birds abundant in Australian desert environments because small mammals are inferior thermoregulators? P. C. Withers1, C. E. Cooper1,2, and W.A. Buttemer3 1Zoology, School of Animal Biology M092, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009 2Present Address: Centre for Behavioural and Physiological Ecology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351 3 Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522 1 Abstract Small desert birds are typically diurnal and highly mobile (hence conspicuous) whereas small non-volant mammals are generally nocturnal and less mobile (hence inconspicuous). Birds are more mobile than terrestrial mammals on a local and geographic scale, and most desert birds are not endemic but simply move to avoid the extremes of desert conditions. Many small desert mammals are relatively sedentary and regularly use physiological adjustments to cope with their desert environment (e.g. aestivation or hibernation). It seems likely that prey activity patterns and reduced conspicuousness to predators have reinforced nocturnality in small desert mammals. Differences such as nocturnality and mobility simply reflect differing life-history traits of birds and mammals rather than being a direct result of their differences in physiological capacity for tolerating daytime desert conditions. Australian desert mammals and birds Small birds are much more conspicuous in Australian desert environments than small mammals, partly because most birds are diurnal, whereas most mammals are nocturnal. Despite birds having over twice the number of species as mammals (ca. 9600 vs. 4500 species, respectively), the number of bird species confined to desert regions is relatively small, and their speciation and endemism are generally low (Wiens 1991). -

An Experimental Investigation of Differential Recovery of Native Rodent

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 001–030 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(1).2019.001-030 An experimental investigation of differential recovery of native rodent remains from Australian palaeontological and archaeological deposits Alexander Baynes1*, Cassia J. Piper2,3 and Kailah M. Thorn2,4 1 Research Associate, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. 2 School of Animal Biology, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia. 3 Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. 4 College of Science & Engineering, Flinders University, Bedford Park, South Australia 5042, Australia. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Quaternary palaeontologists are often asked to identify and interpret faunal remains from archaeological excavations. It is therefore vital that both palaeontologists and archaeologists understand the limitations imposed by recovery methods, especially sieves. Fossil small mammals, particularly rodents, in Australian archaeological deposits are very significant sources of palaeoenvironmental information. Over the last half century, recovery techniques used by archaeologists in Australia have ranged from dry screening with 10 mm sieves to wet screening with nested sieves graded down to 1 mm. Nested 6 and 3 mm sieves have been a popular combination. Experimental investigations, using owl-accumulated mammal remains from two caves, show that sieves of 2 or even 3 mm (the metric equivalent of 1/8th inch) are fine enough to recover most of the dissociated complete jaw bones used to identify Australian native rodents (all Muridae). But they fail to retain first molar teeth that have become dissociated from the jaws by pre-depositional fragmentation, predator digestion or damage during excavation. -

Ethiopia, 2009

Ethiopia trip report, February-March and May 2009 VLADIMIR DINETS (written in February 2016) For a mammalwatcher, Ethiopia is one of the most interesting countries in the world: it has very high mammalian diversity and lots of endemics. It is also poorly explored, with new species of small mammals described every year and new large mammals still discovered occasionally. This means that there is always a chance that you’ll find something new, but it also means that identifying what you see can be very difficult or impossible. I think all larger mammals and bats mentioned below were identified correctly, but I’m still unsure about some shrews and particularly rodents. There are also numerous unsettled taxonomic issues with Ethiopian mammals; I tried to update the taxonomy as well as I could. Travel in Ethiopia isn’t easy or cheap, but it’s totally worth the trouble, and the intensity of cultural experience is unparalleled, although many visitors find it to be a bit too much. The country is catastrophically overpopulated, particularly the fertile highlands. Parks and reserves range from existing only on paper to being relatively well protected, but all of them generate very little income and are deeply hated by the local population; armed conflicts over grazing restrictions are common. I’ve been in Ethiopia three times. In 2005 I got stuck there for a few days due to an airport closure, but had no money at all, couldn’t get out of Addis Ababa, and saw only one bat. In 2009 I went there to study crocodile behavior, spent a few days in Addis arranging special-use permits for national parks, hired a car, traveled to Omo Delta at the northern tip of Lake Turkana, survived ten days of studying crocodiles there, and went to Moyale to meet my volunteers Alexander Bernstein and Sarit Reizin who were coming from Kenya. -

On Mammalian Sperm Dimensions J

On mammalian sperm dimensions J. M. Cummins and P. F. Woodall Reproductive Biology Group, Department of Veterinary Anatomy, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland4067, Australia Summary. Data on linear sperm dimensions in mammals are presented. There is infor- mation on a total of 284 species, representing 6\m=.\2%of all species; 17\m=.\2%of all genera and 49\m=.\2%of all families have some representation, with quantitative information missing only from the orders Dermoptera, Pholidota, Sirenia and Tubulidentata. In general, sperm size is inverse to body mass (except for the Chiroptera), so that the smallest known spermatozoa are amongst those of artiodactyls and the largest are amongst those of marsupials. Most variations are due to differences in the lengths of midpiece and principal piece, with head lengths relatively uniform throughout the mammals. Introduction There is increasing interest in comparative studies of gametes both from the phylogenetic viewpoint (Afzelius, 1983) and also in the analysis of the evolution of sexual reproduction and anisogamy (Bell, 1982; Parker, 1982). This work emerged as part of a review of the relationship between sperm size and body mass in mammals (Cummins, 1983), in which lack of space precluded the inclusion of raw data. In publishing this catalogue of sperm dimensions we wish to rectify this defect, and to provide a reference point for, and stimulus to, further quantitative work while obviating the need for laborious compilation of raw data. Some aspects of the material presented previously (Cummins, 1983) have been re-analysed in the light of new data. Materials and Methods This catalogue of sperm dimensions has been built up from cited measurements, from personal observations and from communication with other scientists. -

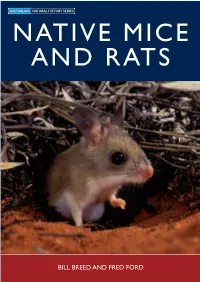

NATIVE MICE and RATS BILL BREED and FRED FORD NATIVE MICE and RATS Photos Courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman

AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD BILL BREED AND RATS MICE NATIVE NATIVE MICE AND RATS Photos courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman Australia’s native rodents are the most ecologically diverse family of Australian mammals. There are about 60 living species – all within the subfamily Murinae – representing around 25 per cent of all species of Australian mammals.They range in size from the very small delicate mouse to the highly specialised, arid-adapted hopping mouse, the large tree rat and the carnivorous water rat. Native Mice and Rats describes the evolution and ecology of this much-neglected group of animals. It details the diversity of their reproductive biology, their dietary adaptations and social behaviour. The book also includes information on rodent parasites and diseases, and concludes by outlining the changes in distribution of the various species since the arrival of Europeans as well as current conservation programs. Bill Breed is an Associate Professor at The University of Adelaide. He has focused his research on the reproductive biology of Australian native mammals, in particular native rodents and dasyurid marsupials. Recently he has extended his studies to include rodents of Asia and Africa. Fred Ford has trapped and studied native rats and mice across much of northern Australia and south-eastern New South Wales. He currently works for the CSIRO Australian National Wildlife Collection. BILL BREED AND FRED FORD NATIVE MICE AND RATS Native Mice 4thpp.indd i 15/11/07 2:22:35 PM Native Mice 4thpp.indd ii 15/11/07 2:22:36 PM AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD Native Mice 4thpp.indd iii 15/11/07 2:22:37 PM © Bill Breed and Fred Ford 2007 All rights reserved. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Elucidating the Evolutionary Consequences of Sociality Through Genome-wide Analyses of Social and Solitary Mammals Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8zr0f93f Author Crawford, Jeremy Chase Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Elucidating the Evolutionary Consequences of Sociality Through Genome-wide Analyses of Social and Solitary Mammals By Jeremy Chase Crawford A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Eileen A. Lacey, Chair Professor George E. Bentley Professor Montgomery W. Slatkin Professor Damian O. Elias Spring 2016 Elucidating the Evolutionary Consequences of Sociality Through Genome-wide Analyses of Social and Solitary Mammals Copyright © 2016 By Jeremy Chase Crawford Abstract Elucidating the Evolutionary Consequences of Sociality Through Genome-wide Analyses of Social and Solitary Mammals by Jeremy Chase Crawford Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Eileen A. Lacey, Chair Social affiliation and group living are seminal aspects of some of the most exciting and intensely studied topics in behavioral biology, from the field of human psychopathology to investigations of cooperation and reproductive skew in animal societies. Understanding how and why sociality evolves as an alternative to the much more common trait of solitary living has long been a topic of special interest among biologists, particularly in light of evidence that group living can impose a number of costs (e.g., increased exposure to pathogens or increased resource competition) that can negatively impact direct fitness.