November2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

Inventing the New Through the Old: the Essence Of

EARLY MODERN JAPAN SPRING 2001 Inventing the New other is the Song scholar Lin Xiyi’s ᨋᏗㅺ2 annotations of the Zhuangzi, which stress that the Through the Old: entire Zhuangzi is a parable. While scholarly The Essence of Haikai opinion differs on which factor or factors played and the Zhuangzi a key role behind the phenomenon, they agree Peipei Qiu that the Danrin’s enthusiasm for the Zhuangzi lies primarily in imitating the gugen in the work.3 Asian Studies Vassar College Introduction meaning, according to Burton Watson, is words put into the mouth of historical or fictional persons to make them more compelling. The Zhuangzi scholars The latter half of the seventeenth century have also used the term to refer to the general writ- witnessed an innovative phenomenon in Japanese ing style of the text. Watson has rendered the haikai େ⺽ (comic linked verse) circles. A meaning of the term into “imported words” in his group of haikai poets who called themselves the translation of the Zhuangzi. The title of Konishi Danrin ⺣ᨋ enthusiastically drew upon the Jin’ichi’s ዊ↟৻ study on Basho and Zhuangzi’s Daoist classic Zhuangzi ⨿ሶ (The works of gugen, “Basho to gugensetsu” ⧊⭈ߣኚ⸒⺑ Master Zhuang), setting off a decade-long trend [Nihon gakushiin kiyo ᣣᧄቇ჻㒮♿ⷐ no. 18 of using the Zhuangzi in haikai composition. In (1960) 2 and 3] is translated into “Basho and assessing the causes and significance of this Chuang-tsu’s Parabolical Phraseology.” The term in phenomenon previous studies give much atten- modern Japanese and Chinese is often translated as tion to the intellectual, philosophical and reli- “fable,” “apologue,” or “parable,” but these transla- gious climates, noting two major factors that in- tions are not suitable to the present study. -

The Wakan Dialectic As Polemic

Purple Displaces Crimson: The Wakan Dialectic as Polemic The cultural phenomenon known as wakan, the creative juxtaposition of Japanese (wa)and Chinese (kan) elements, can be difficult to articulate given the ambiguity involved in defining the boundaries of what makes something Chinese or Japanese, especially over time, or according to the unique perspectives of any given individual. Even at the seemingly irreducible level oflanguage, the apposition oflogographs expressing Chinese poems (kanshi), for example, and syllabic kana script expressing Japanese waka poems are not without nuances that render them fluid, interdependent, and aesthetically unified. Consider a 1682rendition of the Wakan roeishu (FIG.1), the famous eleventh-century anthology of Chinese and Japanese poetry, in which four columns of darkly inked logo graphs render fragments of Chinese poems nearly twice the size of the attenuated columns of kana to the left.' While the powerful Chinese graphs brushed in an assertive running script may at first seem clearly distinct and visually dominant, a closer look reveals an underlying merging of wa and kan in the work through, among other things, the paper decoration. Images of Chinese-style dragons contained within horizontal lines studded with golden dots roil across the upper register of the paper, breathing life into the design suggestive of a variety of associations, from Chinese emperors to serpentine kings beneath the sea. On the other hand, forms reminis cent ofblue clouds, invoking Japanese methods of paper manufacture, encroach toward the center, spilling over and neutralizing the visual force of the dragons, whose golden hue harmonizes with golden hills below. Beneath the calligraphy gold designs ofJapanese bush clover create a local setting for this synesthetic theater of poetic performance. -

Death and Discipleship and Death Kikaku’S

The Rhetoric of Death and Discipleship in Premodern Japan “Horton offers excellent translations of the death accounts of Sōgi and Bashō, along with original answers to two important questions: how disciples of a dying master respond to his death The Rhetoric of in their own relationships and practices and how they represent loss and recovery in their own writing. A masterful study, well Death and Discipleship researched and elegantly written.” —Steven D. Carter, Stanford University in Premodern Japan “Meticulous scholarship and elegant translation combine in this revelatory presentation of the ‘versiprose’ accounts of the deaths of two of the most famous linked-verse masters, Sōgi and Bashō, written by their disciples Sōchō and Kikaku.” —Laurel Rasplica Rodd, University of Colorado at Boulder “Mack Horton has a deep knowledge of the life and work of these two great Japanese poets, a lifetime of scholarship reflect- ed everywhere in the volume’s introduction, translations, and detailed explanatory notes. This is a model of what an anno- tated translation should be.” Horton —Machiko Midorikawa, Waseda University INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES INSTITUTE OF EAST Sōchō’s Death of Sōgi and Kikaku’s Death of Master Bashō H. Mack Horton is Professor of Premodern Japanese Literature in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Berkeley. H. Mack Horton INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES JRM 19 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ● BERKELEY CENTER FOR JAPANESE STUDIES JAPAN RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 19 JRM 19_F.indd 1 9/18/2019 1:43:04 PM Notes to this edition This is an electronic edition of the printed book. -

Nature And/Or Poetry? Based on “A Poem of One Hundred Links Composed by Three Poets at Minase” (Minase Sangin Hyakuin, 1488)

Nature and/or poetry? Based on “A Poem of One Hundred Links Composed by Three Poets at Minase” (Minase Sangin Hyakuin, 1488) Elena Mikhailovna DYAKONOVA Iio Sogi is the best known renga master of Japan. He was of low origin (which is said by every encyclopedia and biographic essay); his family was in the service of the Sasaki clan. Some sources say the poet’s father was a Sarugaku Noh teach- er, while others call him a Gigaku master; and his mother was born to an insignificant samurai clan, Ito. The image of Sogi – an old man, a traveler with a beard wearing old clothes and living in a shack – looks hagiographic and conven- tional Zen, rather than something real. Renga (linked-verse poetry) is a chain of tercets and distiches (17 syllables and 14 syllables), which is sometimes very long, up to a hundred, a thousand, or even 10,000 stanzas built on the same metric principle, in which a stanza com- prising a group of five syllables and a group of seven syllables (5-7-5 and 7-7) in a line, is the prosodic unit. All those tercets and distiches, which are often com- posed by different authors in a roll call, are connected by the same subject (dai), but do not share the narrative. Every tercet and distich is an independent work on the subject of love, separation, and loneliness embedded in a landscape and can be easily removed from the poem without damaging its general context, although it is related to the adjoining stanzas. Keywords: renga, poetry, Sogi, Minase Sangin Hyakuin, Emperer Go-Toba On the 22nd day of the 1st moon cycle of the 2nd year of the Chokyo era (1488), three famed poets – renga master Sogi (1421–1502) and his pupils, Shohaku (1443–1527) and Socho (1448–1532), – gathered by the Go-Toba Goeido pavilion, the Minase Jingu Shinto sanctuary in Minase between Kyo- to and Osaka, to compose a poem of one hundred links commemorating the 250th death anniversary of Emperor Go-Toba. -

Matsuo ■ Basho

; : TWAYNE'S WORLD AUTHORS SERIES A SURVEY OF THE WORLD'S LITERATURE ! MATSUO ■ BASHO MAKOTO UEDA JAPAN MATSUO BASHO by MAKOTO UEDA The particular value of this study of Matsuo Basho is obvious: this is the first book in English that gives a comprehen sive view of the famed Japanese poet’s works. Since the Japanese haiku was en thusiastically received by the Imagists early in this century, Basho has gained a world-wide recognition as the foremost writer in that miniature verse form; he is now regarded as a poet of the highest cali ber in world literature. Yet there has been no extensive study of Basho in Eng lish, and consequently he has remained a rather remote, mystical figure in the minds of those who do not read Japanese. This book examines Basho not only as a haiku poet but as a critic, essayist and linked-verse writer; it brings to light the whole range of his literary achievements that have been unknown to most readers in the West. * . 0S2 VS m £ ■ ■y. I.. Is:< i , • ...' V*-, His. -.« ■ •. '■■ m- m mmm t f ■ ■ m m m^i |«|mm mmimM plf^Masstfa m*5 si v- mmm J 1 V ^ K-rZi—- TWAYNE’S WORLD AUTHORS SERIES A Survey of the World's Literature Sylvia E. Bowman, Indiana University GENERAL EDITOR JAPAN Roy B. Teele, The University of Texas EDITOR Matsuo Basho (TWAS 102) TWAYNES WORLD AUTHORS SERIES (TWAS) The purpose of TWAS is to survey the major writers — novelists, dramatists, historians, poets, philosophers, and critics—of the nations of the world. -

Matsuo Basho - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Matsuo Basho - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Matsuo Basho(1644 - 1694) Bashō was born Matsuo Kinsaku around 1644, somewhere near Ueno in Iga Province. His father may have been a low-ranking samurai, which would have promised Bashō a career in the military but not much chance of a notable life. It was traditionally claimed by biographers that he worked in the kitchens. However, as a child Bashō became a servant to Tōdō Yoshitada, who shared with Bashō a love for haikai no renga, a form of cooperative poetry composition. The sequences were opened with a verse in the 5-7-5 mora format; this verse was named a hokku, and would later be renamed haiku when presented as stand-alone works. The hokku would be followed by a related 7-7 addition by another poet. Both Bashō and Yoshitada gave themselves haigō, or haikai pen names; Bashō's was Sōbō, which was simply the on'yomi reading of his samurai name of Matsuo Munefusa. In 1662 the first extant poem by Bashō was published; in 1664 two of his hokku were printed in a compilation, and in 1665 Bashō and Yoshitada composed a one-hundred-verse renku with some acquaintances. Yoshitada's sudden death in 1666 brought Bashō's peaceful life as a servant to an end. No records of this time remain, but it is believed that Bashō gave up the possibility of samurai status and left home. -

A Study of Japanese Aesthetics in Six Parts by Robert Wilson

A Study of Japanese Aesthetics in Six Parts by Robert Wilson Table of Contents Part 1: The Importance of Ma .......................................................p. 2-20 Reprinted from Simply Haiku, Winter 2011, Vol. 8, No. 3. Part 2: Reinventing The Wheel: The Fly Who Thought He Was a Carabaop.................................................................................................p. 21-74 Reprinted from Simply Haiku, Vol. 9. No. 1, Spring 2011 Part 3: To Kigo or Not to Kigo: Hanging From a Marmot’s Mouth ....................................................................................................................p. 75-110 Reprinted from Simply Haiku Summer 2011 Part 4: Is Haiku Dying?....................................................................p. 111-166 Reprinted from Simply Haiku Autumn 2011?Winter 2012 Part 5: The Colonization of JapaneseHaiku .........................p. 167-197 Reprinted from Simply Haiku Summer 2012. Part 6: To Be Or Not To Be: An Experiment Gone Awry....p 198-243 Republished from Simple Haiku, Spring-Summer 2013. Conclusion—What Is and Isn't: A Butterfly Wearing Tennis Shoes ..................................................................................................................p. 244-265 Republished from Simply Haiku Winter 2013. Study of Japanese Aesthetics: Part I The Importance of Ma by Robert Wilson "The man who has no imagination has no wings." - Muhammad Ali Every day I read haiku and tanka online in journals and see people new to these two Japanese genres posting three to five -

HARDLY STRICTLY HAIKAI —An Introduction—

HARDLY STRICTLY HAIKAI —An Introduction— Haikai no Renga is collaborative poetry of Japanese origin normally written by two or more poets linking stanzas of 17 syllables and 14 syllables according to specific rules governing the relationship between stanzas. Haikai collaboration can be as complex as chess, as multi-dimensional as go, and as fast-paced and entertaining as dominoes. It is as much about the interaction of the poets as it is about what gets written. The forward progress of its improvisation is akin to that of a tight jazz combo. Haikai composition has also been compared to montage in experimental film where the discontinuity of images and vectors achieves an integral non-narrative expression. Haikai no renga is known variously as renga, haikai, renku, and linked poetry. Generally the term renga is applied to an older, more traditional style of linking poetry practiced by the aristocracy and the upper echelon of medieval Japanese society. Haikai no renga means “non-standard renga” though it has often been translated as “mongrel” or “dog renga” which places it in the literary hierarchy as common entertainment. In the introduction to her seminal study of Matsuo Basho’s haikai no renga, Monkey’s Raincoat (Grossinger/Mushinsha, 1973), Dr. Maeda Cana offers a further explication of the word haikai. “The main characteristics of the haikai are partly discernible in the kanji or Chinese characters which make up the words haikai and renku: hai denotes fun, play, humor, and also actor or actress, and kai friendly exchange of words; ren represents a number of carriages passing along a road one after another and has the meaning of continuing to completion while ku is expressive of the rhythmic changes in speech and denotes end or stop.” Renku is a literary game of high seriousness valuing cooperation and rewarding intelligence as well as intuition. -

Monkey's Raincoat

Monkey’s Raincoat by Matsuo Basho translated by Maeda Cana i Matsuo basho is the leading figure in the history not only of the 17-syllable haiku form, but also of haikai renga (1renku), that unique form of “linked” verse composed by several poets collectively under the poetic supervision and spiritual guidance of the Master. Sarumino, or Monkey’s Raincoat, the fifth of the seven major anthologies of poetry by Bash5 and his disciples, was published in 1691 in two volumes. It was during 1690, when Bash5 spent considerable time in Kyoto and Omi, that, under his leadership, the anthology was compiled by i Kyorai and Bonch5. It includes four renku in the kaseti form (36 verses) and haiku by poets from all over Japan, but mainly from the Kyoto area. The title is derived from the opening poem: First winter rain/the monkey wantsja raincoat too. Monkey’s Raincoat is generally considered to represent % the best and most typical work of Basho’s mature style, and clearly reflects the depth of his attitude to life and poetry achieved during his pilgrimage to the Back Roads to Far Towns (Oku no hosomichi) in 1689. The current translation, by Maeda Cana, is of the four renku from the anthology: Winter’s First Shower, Summer Moon, Katydid, and Plum Young Herbs. To the right of each verse the poet is indicated, and there is a general commen > tary to the left which attempts to put the poetry in its cultural and psychological contexts, as well as to pin down I some of the subtleties of the “linking” process. -

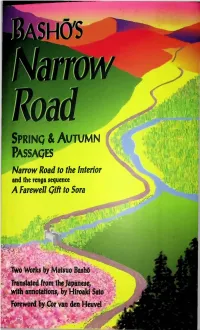

Spring &Autumn

Spring & Autumn Passages Narrow Road to the Interior and the renga sequence A Farewell Qift to Sora iV-y, . p^: Two Works by Matsuo BasM Translated from the Japanese, with annotations, by Hiroaki Sato Foreword by Cor van den Heuvel '-f BASHO'S NARROW ROAD i j i ; ! ! : : ! I THE ROCK SPRING COLLECTION OF JAPANESE LITERATURE ; BaSHO'S Narrow Road SPRINQ & AUTUMN PASSAQES Narrow Road to the Interior AND THE RENGA SEQUENCE A Farewell Gift to Sora TWO WORKS BY MATSUO BASHO TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE, WITH ANNOTATIONS, BY Hiroaki Sato FOREWORD BY Cor van den Heuvel STONE BRIDGE PRESS • Berkeley,, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O, Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stoncbridgc.com Cover design by Linda Thurston. Text design by Peter Goodman. Text copyright © 1996 by Hiroaki Sato. Signature of the author on front part-title page: “Basho.” Illustrations by Yosa Buson reproduced by permission of Itsuo Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG1NG-1N-PUBL1 CATION DATA Matsuo, BashO, 1644-1694. [Oku no hosomichi. English] Basho’s Narrow road: spring and autumn passages: two works / by Matsuo Basho: translated from the Japanese, with annotations by Hiroaki Sato. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Narrow road to the interior and the renga sequence—A farewell gift to Sora. ISBN 1-880656-20-5 (pbk.) 1- Matsuo, Basho, 1644-1694—Journeys—Japan. -

The Narrow Road to the Deep North Matsuo Basho

The Narrow Road to the Deep North Matsuo Basho Page 1 MATSUO BASHO OKU NO HOSOMICHI THE NARROW ROAD TO THE DEEP NORTH © www.tclt.org.uk [In the translation, the term indicates further explanation or discussion of a particular crux. Click on the term for an immediate transfer to that discussion, and then on RETURN to come back to the translation]. Table of Contents The Narrow Road to the Deep North………………………………………………………….4 Wikipedia Article about The Narrow Road to the Deep North ………………………………52 Wikipedia Article about Matsuo Basho ……………………………………………………...53 National Geographic article following Basho’s trail ………………………………...………58 Maps of Basho’s travels ……………………………………………………………………...63 Basho’s Poems ………………..……………………………………………………………...64 Translations of The Old Pond ………………………………………………………………..69 . Page 2 <出発まで > 月日は百代の過客にして行かふ年も又旅人也。 舟の上に生涯をう かべ、馬の口とらえて老をむかふる物は日々旅にして旅を栖とす 。 古人も多く旅に死せるあり。 予もいづれの年よりか片雲の風に さそはれて、漂白の思ひやまず、海濱にさすらへ、去年の秋江上 の破屋に蜘の古巣をはらひてやゝ年も暮、春立る霞の空に白川の 関こえんと、そゞろ神の物につきて心をくるはせ、道祖神のまね きにあひて、取もの手につかず。 もゝ引の破をつゞり、笠の緒付 かえて、三里に灸すゆるより、松嶋の月先心にかゝりて、住る方 は人に譲り、杉風が別墅に移るに、 草の戸も住替る代ぞひなの家 面八句を庵の柱に懸置。 The days and months are travelers of eternity, just like the years that come and go. For those who pass their lives afloat on boats, or face old age leading horses tight by the bridle, their journeying is life, their journeying is home. And many are the men of old who met their end upon the road. How long ago, I wonder, did I see a drift of cloud borne away upon the wind, and ceaseless dreams of wandering become aroused? Only last year, I had been wandering along the coasts and bays; and in the autumn, I swept away the cobwebs from my tumbledown hut on the banks of the Sumida and soon afterwards saw the old year out.