Benzoquinones in the Defensive Secretion of a Bug (Pamillia Behrensii): a Common Chemical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green-Tree Retention and Controlled Burning in Restoration and Conservation of Beetle Diversity in Boreal Forests

Dissertationes Forestales 21 Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Esko Hyvärinen Faculty of Forestry University of Joensuu Academic dissertation To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu, for public criticism in auditorium C2 of the University of Joensuu, Yliopistonkatu 4, Joensuu, on 9th June 2006, at 12 o’clock noon. 2 Title: Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Author: Esko Hyvärinen Dissertationes Forestales 21 Supervisors: Prof. Jari Kouki, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Docent Petri Martikainen, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Pre-examiners: Docent Jyrki Muona, Finnish Museum of Natural History, Zoological Museum, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Docent Tomas Roslin, Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Division of Population Biology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Opponent: Prof. Bengt Gunnar Jonsson, Department of Natural Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden ISSN 1795-7389 ISBN-13: 978-951-651-130-9 (PDF) ISBN-10: 951-651-130-9 (PDF) Paper copy printed: Joensuun yliopistopaino, 2006 Publishers: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Finnish Forest Research Institute Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Helsinki Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu Editorial Office: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Unioninkatu 40A, 00170 Helsinki, Finland http://www.metla.fi/dissertationes 3 Hyvärinen, Esko 2006. Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests. University of Joensuu, Faculty of Forestry. ABSTRACT The main aim of this thesis was to demonstrate the effects of green-tree retention and controlled burning on beetles (Coleoptera) in order to provide information applicable to the restoration and conservation of beetle species diversity in boreal forests. -

Dung Beetles: Key to Healthy Pasture? an Overview

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 153(2) (2021) 93-123 EISSN 2392-2192 Dung beetles: key to healthy pasture? An overview Sumana Saha1,a, Arghya Biswas1,b, Avirup Ghosh1,c and Dinendra Raychaudhuri2,d 1Post Graduate Department of Zoology, Barasat Government College, 10, K.N.C. Road, Barasat, Kolkata – 7000124, India 2IRDM Faculty Centre, Department of Agricultural Biotechnology, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University, Narendrapur, Kolkata – 700103, India a,b,c,dE-mail address: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) do just what their name suggests: they use the manure, or dung of other animals in some unique ways! Diversity of the coprine members is reflected through the differences in morphology, resource relocation and foraging activity. They use one of the three broad nesting strategies for laying eggs (Dwellers, Rollers, Tunnelers and Kleptocoprids) each with implications for ecological function. These interesting insects fly around in search of manure deposits, or pats from herbivores like cows and elephants. Through manipulating faeces during the feeding process, dung beetles initiate a series of ecosystem functions ranging from secondary seed dispersal to nutrient cycling and parasite suppression. The detritus-feeding beetles play a small but remarkable role in our ecosystem. They feed on manure, use it to provide housing and food for their young, and improve nutrient cycling and soil structure. Many of the functions provide valuable ecosystem services such as biological pest control, soil fertilization. Members of the genus Onthophagus have been widely proposed as an ideal group for biodiversity inventory and monitoring; they satisfy all of the criteria of an ideal focal taxon, and they have already been used in ecological research and biodiversity survey and conservation work in many regions of the world. -

Insecta: Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae), with a Description of Sciaphyes Shestakovi Sp.N

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Arthropod Systematics and Phylogeny Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 69 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fresneda Javier, Grebennikov Vasily V., Ribera Ignacio Artikel/Article: The phylogenetic and geographic limits of Leptodirini (Insecta: Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae), with a description of Sciaphyes shestakovi sp.n. from the Russian Far East 99-123 Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 99 69 (2) 99 –123 © Museum für Tierkunde Dresden, eISSN 1864-8312, 21.07.2011 The phylogenetic and geographic limits of Leptodirini (Insecta: Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae), with a description of Sciaphyes shestakovi sp. n. from the Russian Far East JAVIER FRESNEDA 1, 2, VASILY V. GREBENNIKOV 3 & IGNACIO RIBERA 4, * 1 Ca de Massa, 25526 Llesp, Lleida, Spain 2 Museu de Ciències Naturals (Zoologia), Passeig Picasso s/n, 08003 Barcelona, Spain [[email protected]] 3 Ottawa Plant Laboratory, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0C6, Canada [[email protected]] 4 Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-UPF), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37 – 49, 08003 Barcelona, Spain [[email protected]] * Corresponding author Received 26.iv.2011, accepted 27.v.2011. Published online at www.arthropod-systematics.de on 21.vii.2011. > Abstract The tribe Leptodirini of the beetle family Leiodidae is one of the most diverse radiations of cave animals, with a distribution centred north of the Mediterranean basin from the Iberian Peninsula to Iran. Six genera outside this core area, most notably Platycholeus Horn, 1880 in the western United States and others in East Asia, have been assumed to be related to Lepto- dirini. -

Downloaded Public Available GWAS

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.26.888313; this version posted December 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 1 The interplay between host genetics and the gut microbiome reveals common 2 and distinct microbiome features for human complex diseases 3 Fengzhe Xu1#, Yuanqing Fu1#, Ting-yu Sun2, Zengliang Jiang1,3, Zelei Miao1, Menglei 4 Shuai1, Wanglong Gou1, Chu-wen Ling2, Jian Yang4,5, Jun Wang6*, Yu-ming Chen2*, 5 Ju-Sheng Zheng1,3,7* 6 #These authors contributed equally to the work 7 1 School of Life Sciences, Westlake University, Hangzhou, China. 8 2 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Food, Nutrition and Health; Department 9 of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 10 China. 11 3 Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Westlake Institute for Advanced Study, 12 Hangzhou, China. 13 4 Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, 14 Australia. 15 5 Institute for Advanced Research, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, Zhejiang 16 325027, China 17 6 CAS Key Laboratory for Pathogenic Microbiology and Immunology, Institute of 18 Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China. 19 7 MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 20 21 Short title: Interplay between and host genetics and gut microbiome 22 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.26.888313; this version posted December 26, 2019. -

Introduced Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) in the Maritime Provinces of Canada

48 Introduced Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) in the Maritime Provinces of Canada Christopher G. Majka1 Nova Scotia Museum, 1747 Summer Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3H 3A6 Jan Klimaszewski Laurentian Forestry Centre, Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources Canada, 1055 de P.E.P.S., P.O. Box 10380, Stn. Sainte-Foy, Québec, Quebec, Canada G1V 4C7 Abstract—The fauna of introduced rove beetles (Staphylinidae) in the Maritime Provinces of Canada is surveyed. Seventy-nine species have now been recorded. Of these, 73 have been found in Nova Scotia, 29 on Prince Edward Island, and 54 in New Brunswick. Twenty-five species are newly recorded in Nova Scotia, 16 on Prince Edward Island, and 10 in New Brunswick, for a total of 51 new provincial records. Of these, 15 species, Tachinus corticinus Gravenhorst, Mycetoporus lepidus (Gravenhorst), Habrocerus capillaricornis (Gravenhorst), Aleochara (Xenochara) lanuginosa Gravenhorst, Gnypeta caerulea (C.R. Sahlberg), Atheta (Microdota) amicula (Stephens), Cordalia obscura (Gravenhorst), Drusilla canaliculata (Fabricius), Deleaster dichrous (Gravenhorst), Coprophilus striatulus (Fabricius), Carpelimus subtilis (Erichson), Leptacinus intermedius Donisthorpe, Tasgius (Rayacheila) melanarius (Heer), Neobisnius villosulus (Stephens), and Philonthus discoideus (Gravenhorst), are newly recorded in the Maritime Prov- inces. Two of these, Atheta (Microdota) amicula and Carpelimus subtilis, are newly recorded in Canada. Leptacinus intermedius is removed from the faunal list of New Brunswick and Philhygra botanicarum Muona, a Holarctic species previously regarded as introduced in North America, is re- corded for the first time in the Maritime Provinces. An examination of when species were first de- tected in the region reveals that, on average, it was substantially later than comparable dates for other, better known families of Coleoptera — an apparent indication of the comparative lack of at- tention this family has received. -

Effects of Urbanisation and Urban Areas on Biodiversity

From genes to habitats – effects of urbanisation and urban areas on biodiversity Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaflichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Gwendoline (Wendy) Altherr aus Trogen, Appenzell-Ausserrhoden Basel, 2007 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch–Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Peter Nagel, Prof. Dr. Patricia Holm, Prof. (em.) Dr. Bernhard Klausnitzer Basel, den 18. September 2007 Prof. Dr. Hans-Peter Hauri Dekan TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 1 General introduction – biodiversity in the city 3 Chapter I – genetic diversity 21 Population genetic structure of the wall lizard (Podarcis muralis) in an urban environment Manuscript Chapter II – species diversity 47 How do small urban forest patches contribute to the biodiversity 47 of the arthropod fauna? Manuscript Leistus fulvibarbis Dejean – Wiederfund einer verschollenen 79 Laufkäferart (Coleoptera, Carabidae) in der Schweiz Veröffentlicht in den Mitteilungen der Entomologischen Gesellschaft Basel 56(4), 2006 Chapter III – habitat diversity 89 How do stakeholders and the legislation influence the allocation of green space on brownfield redevelopment projects? Five case studies from Switzerland, Germany and the UK Published in Business Strategy and the Environment 16, 2007 General discussion and conclusions 109 Acknowledgements 117 Curriculum Vitae 119 SUMMARY Urban areas are landscapes dominated by built-up structures for human use. Nevertheless, nature can still be found within these areas. Urban ecosystems can offer ecological niches, sometimes only found in cities. This biodiversity in the form of genetic diversity, species diversity and habitat diversity provided the structure of this thesis. First, we studied the effects of urbanisation on genetic diversity. We analysed the population structure of the wall lizard with highly variable genetic markers. -

Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) Associated to Cattle Dung in Campo Grande, MS, Brazil

October - December 2002 641 SCIENTIFIC NOTE Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) Associated to Cattle Dung in Campo Grande, MS, Brazil WILSON W. K OLLER1,2, ALBERTO GOMES1, SÉRGIO R. RODRIGUES3 AND JÚLIO MENDES 4 1Embrapa Gado de Corte, C. postal 154, CEP 79002-970, Campo Grande, MS 2 [email protected] 3Universidade Estadual de Mato Grosso do Sul - UEMS, Aquidauana, MS 4Universidade Federal de Uberlândia - UFU, Uberlândia, MG Neotropical Entomology 31(4):641-645 (2002) Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) Associados a Fezes Bovinas em Campo Grande, MS RESUMO - Este trabalho foi executado com o objetivo de determinar as espécies locais de estafilinídeos fimícolas, devido à importância destes predadores e ou parasitóides no controle natural de parasitos de bovinos associadas às fezes. Para tanto, massas fecais com 1, 2 e 3 dias de idade foram coletadas semanalmente em uma pastagem de Brachiaria decumbens Stapf, no período de maio de 1990 a abril de 1992. As fezes foram acondicionadas em baldes plásticos, opacos, com capacidade para 15 litros, contendo aberturas lateral e no topo, onde foram fixados frascos para a captura, por um período de 40 dias, dos besouros estafilinídeos presentes nas massas fecais. Após este período a massa fecal e o solo existente nos baldes eram examinados e os insetos remanescentes recolhidos. Foi coletado um total de 13.215 exemplares, pertencendo a 34 espécies e/ou morfo espécies. Foram observados os seguintes doze gêneros: Oxytelus (3 espécies; 70,1%); Falagria (1 sp.; 7,9); Aleochara (4 sp.; 5,8); Philonthus (3 sp.; 5,1); Atheta (2 sp.; 4,0); Cilea (2 sp.; 1,2); Neohypnus (1 sp.; 0,7); Lithocharis (1 sp.; 0,7); Heterothops (2 sp.; 0,6); Somoleptus (1 sp.; 0,08); Dibelonetes (1 sp.; 0,06) e, Dysanellus (1 sp.; 0,04). -

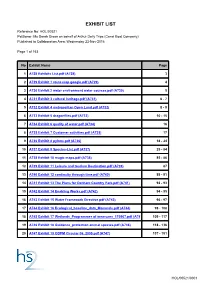

Exhibit List

EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 1 of 163 No Exhibit Name Page 1 A728 Exhibits List.pdf (A728) 3 2 A729 Exhibit 1 route map google.pdf (A729) 4 3 A730 Exhibit 2 water environment water courses.pdf (A730) 5 4 A731 Exhibit 3 cultural heritage.pdf (A731) 6 - 7 5 A732 Exhibit 4 metropolitan Open Land.pdf (A732) 8 - 9 6 A733 Exhibit 5 dragonflies.pdf (A733) 10 - 15 7 A734 Exhibit 6 quality of water.pdf (A734) 16 8 A735 Exhibit 7 Customer activities.pdf (A735) 17 9 A736 Exhibit 8 pylons.pdf (A736) 18 - 24 10 A737 Exhibit 9 Species-List.pdf (A737) 25 - 84 11 A738 Exhibit 10 magic maps.pdf (A738) 85 - 86 12 A739 Exhibit 11 Leisure and tourism Destination.pdf (A739) 87 13 A740 Exhibit 12 continuity through time.pdf (A740) 88 - 91 14 A741 Exhibit 13 The Plans for Denham Country Park.pdf (A741) 92 - 93 15 A742 Exhibit 14 Enabling Works.pdf (A742) 94 - 95 16 A743 Exhibit 15 Water Framework Directive.pdf (A743) 96 - 97 17 A744 Exhibit 16 Ecological_baseline_data_Mammals.pdf (A744) 98 - 108 18 A745 Exhibit 17 Wetlands_Programmes of measures_170907.pdf (A745) 109 - 117 19 A746 Exhibit 18 Guidance_protection animal species.pdf (A746) 118 - 136 20 A747 Exhibit 19 ODPM Circular 06_2005.pdf (A747) 137 - 151 HOL/00521/0001 EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 2 of 163 No Exhibit -

An Inventory of Nepal's Insects

An Inventory of Nepal's Insects Volume III (Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera & Diptera) V. K. Thapa An Inventory of Nepal's Insects Volume III (Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera& Diptera) V.K. Thapa IUCN-The World Conservation Union 2000 Published by: IUCN Nepal Copyright: 2000. IUCN Nepal The role of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in supporting the IUCN Nepal is gratefully acknowledged. The material in this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for education or non-profit uses, without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. IUCN Nepal would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication, which uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purposes without prior written permission of IUCN Nepal. Citation: Thapa, V.K., 2000. An Inventory of Nepal's Insects, Vol. III. IUCN Nepal, Kathmandu, xi + 475 pp. Data Processing and Design: Rabin Shrestha and Kanhaiya L. Shrestha Cover Art: From left to right: Shield bug ( Poecilocoris nepalensis), June beetle (Popilla nasuta) and Ichneumon wasp (Ichneumonidae) respectively. Source: Ms. Astrid Bjornsen, Insects of Nepal's Mid Hills poster, IUCN Nepal. ISBN: 92-9144-049 -3 Available from: IUCN Nepal P.O. Box 3923 Kathmandu, Nepal IUCN Nepal Biodiversity Publication Series aims to publish scientific information on biodiversity wealth of Nepal. Publication will appear as and when information are available and ready to publish. List of publications thus far: Series 1: An Inventory of Nepal's Insects, Vol. I. Series 2: The Rattans of Nepal. -

Hox-Logic of Body Plan Innovations for Social Symbiosis in Rove Beetles

bioRxiv preprint first posted online Oct. 5, 2017; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/198945. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not peer-reviewed) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Hox-logic of body plan innovations for social symbiosis in rove beetles 2 3 Joseph Parker1*, K. Taro Eldredge2, Isaiah M. Thomas3, Rory Coleman4 and Steven R. Davis5 4 5 1Division of Biology and Biological Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, 6 CA 91125, USA 7 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Division of Entomology, Biodiversity 8 Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 9 3Department of Genetics and Development, Columbia University, 701 West 168th Street, New 10 York, NY 10032, USA 11 4Laboratory of Neurophysiology and Behavior, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065, 12 USA 13 5Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, 14 USA 15 *correspondence: [email protected] 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 1 bioRxiv preprint first posted online Oct. 5, 2017; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/198945. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not peer-reviewed) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 How symbiotic lifestyles evolve from free-living ecologies is poorly understood. In 2 Metazoa’s largest family, Staphylinidae (rove beetles), numerous lineages have evolved 3 obligate behavioral symbioses with ants or termites. -

Hox-Logic of Preadaptations for Social Insect Symbiosis in Rove Beetles

bioRxiv preprint first posted online Oct. 5, 2017; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/198945. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Hox-logic of preadaptations for social insect symbiosis in rove beetles Joseph Parker1*, K. Taro Eldredge2, Isaiah M. Thomas3, Rory Coleman3 and Steven R. Davis3,4 1Division of Biology and Biological Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Division of Entomology, Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 3Department of Genetics and Development, Columbia University, 701 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA 4Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA *correspondence: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint first posted online Oct. 5, 2017; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/198945. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. How symbiotic lifestyles evolve from free-living ecologies is poorly understood. Novel traits mediating symbioses may stem from preadaptations: features of free- living ancestors that predispose taxa to engage in nascent interspecies relationships. In Metazoa’s largest family, Staphylinidae (rove beetles), the body plan within the subfamily Aleocharinae is preadaptive for symbioses with social insects. Short elytra expose a pliable abdomen that bears targetable glands for host manipulation or chemical defense. The exposed abdomen has also been convergently refashioned into ant- and termite-mimicking shapes in multiple symbiotic lineages. Here we show how this preadaptive anatomy evolved via novel Hox gene functions that remodeled the ancestral coleopteran groundplan. -

What Do Rove Beetles (Coleoptera: Staphy- Linidae) Indicate for Site Conditions? 439-455 ©Faunistisch-Ökologische Arbeitsgemeinschaft E.V

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Faunistisch-Ökologische Mitteilungen Jahr/Year: 2000-2007 Band/Volume: 8 Autor(en)/Author(s): Irmler Ulrich, Gürlich Stephan Artikel/Article: What do rove beetles (Coleoptera: Staphy- linidae) indicate for site conditions? 439-455 ©Faunistisch-Ökologische Arbeitsgemeinschaft e.V. (FÖAG);download www.zobodat.at Faun.-6kol.Mitt 8, 439-455 Kiel, 2007 What do rove beetles (Coleoptera: Staphy- linidae) indicate for site conditions? By Ulrich Irmler & Stephan Giirlich Summary Although the rove beetle family is one of the most species rich insect families, it is ecologically rarely investigated. Little is known about the influence of environmental demands on the occurrence of the species. Thus, the present investigation aims to relate rove beetle assemblages and species to soil and forest parameters of Schleswig- Holstein (northern Germany). In the southernmost region of Schleswig-Holstein near Geesthacht, 65 sites were investigated by pitfall traps studying the relationship be tween the rove beetle fauna and the following environmental parameters: soil pH, organic matter content, habitat area and canopy cover. In total 265 rove beetle species have been recorded, and of these 69 are listed as endangered in Schleswig-Holstein. Four assemblages could be differentiated, but separation was weak. Wood area and canopy cover were significantly related with the rove beetle composition using a multivariate analysis. In particular, two assemblages of loosely wooded sites, or heath-like vegetation, were significantly differentiated from the densely forested assemblages by canopy cover and Corg-content of soil. Spearman analysis revealed significant results for only 30 species out of 80.