Of Rats and Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathmatters and STEAM Expo

Winter 2016-2017 NEWSLETTER MathMatters and STEAM Expo On Saturday, March 18th, Coral Academy of Science Las Vegas will host the 13th annual math contest, MathMatters and our annual STEAM Expo. Executive Director Letter This marks the first year both events will happen concurrently. Central Office Note Our long-established K-12 STEAM Expo is going to be held at Sandy Ridge Sandy Ridge Principal’s Park, Henderson. Students from all five branches of Coral Academy of Note Science, Las Vegas will come together to make this amazing event more Upcoming Events fascinating. Additionally this year there will be art booths as well. This 2017-2018 Calendar free event will help raise funds for many clubs and groups as well as ex- pose our community to all that our students have to offer. Nellis AFB Principal’s Note MathMatters will be held at the Sandy Ridge Campus. The event is free Centennial Hills and open to all 4th and 5th grade students throughout the Las Vegas Val- Principal’s Note ley but pre-registration is required. Students will test their skills by solv- ing 15 challenging math questions ranging from fractions to operations Windmill Principal’s and algebraic thinking. All attendees will enjoy the science demonstra- Note tion on defying gravity by Mad Science of Las Vegas. Tamarus Principal’s Note Winners of the competition will win prizes including: 1st place prize: IPAD Mini2 Accolades 2nd place prize: Kindle Fire HD 8 Student Highlights 3rd place prize: Kindle Fire MathMatters registration information will be coming soon. Reminders We are now accepting online applications for the 2017-2018 school year. -

Tvtimes Are Calling Every Day Is Exceptional at Meadowood Call 812-336-7060 to Tour

-711663-1 HT AndyMohrHonda.com AndyMohrHyundai.com S. LIBERTY DRIVE BLOOMINGTON, IN THE HERALD-TIMES | THE TIMES-MAIL | THE REPORTER-TIMES | THE MOORESVILLE-DECATUR TIMES August 3 - 9, 2019 NEW ADVENTURES TVTIMES ARE CALLING EVERY DAY IS EXCEPTIONAL AT MEADOWOOD CALL 812-336-7060 TO TOUR. -577036-1 HT 2455 N. Tamarack Trail • Bloomington, IN 47408 812-336-7060 www.MeadowoodRetirement.com 2019 Pet ©2019 Five Star Senior Living Friendly Downsizing? CALL THE RESULTS TEAM Brokered by: | Call Jenivee 317-258-0995 or Lesaesa 812-360-3863 FREE DOWNSIZING Solving Medical Mysteries GUIDE “Flip or Flop” star and former cancer patient Tarek El -577307-1 Moussa is living proof behind the power of medical HT crowdsourcing – part of the focus of “Chasing the Cure,” a weekly live broadcast and 24/7 global digital platform, premiering Thursday at 9 p.m. on TNT and TBS. Senior Real Estate Specialist JENIVEE SCHOENHEIT LESA OLDHAM MILLER Expires 9/30/2019 (812) 214-4582 HT-698136-1 2019 T2 | THE TV TIMES| The Unacknowledged ‘Mother of Modern Dish Communications’ Bedford DirecTV Cable Mitchell Comcast Comcast Comcast New Wave New New Wave New Mooreville Indianapolis Indianapolis Bloomington Conversion Martinsviolle BY DAN RICE television for Lionsgate. “It is one of those rare initiatives that WTWO NBC E@ - - - - - - - With the availability, cost E# seeks to inspire with a larger S WAVE NBC - 3 - - - - - and quality of healthcare being $ A WTTV CBS E 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 humanitarian purpose, and T such hot-button issues these E^ WRTV ABC 6 6 6 6 - 6 6 URDAY, -

The Complete X-Files Ebook

THE COMPLETE X-FILES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chris Knowles,Matt Hurwitz | 224 pages | 23 Sep 2016 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781785654336 | English | London, United Kingdom The Complete X-Files PDF Book In one of the most tongue in cheek, unusual episodes of the series, Scully consults with a Truman Capote-like novelist who wants to write "non- fiction science fiction" based around an unusual x-file, giving an outsider's perspective to a case. You may not need files for most quick fixes. It's an unnerving, calculating episode, where the mere appearance of Modell onscreen spells very bad thing. There's also a lot of heart in the episode, with Boyle portraying a sensitive, gruff loner dealing with the worst of curses. The episode seems to be heavily influenced by the works of H. Essentially, the episode is about the government using television signals to drive people to madness. This not only makes filing faster but makes it much easier to find documents afterward. An FBI manhunt ensues, with agents in pursuit of an antagonist that can alter their very perceptions of reality. The beauty of customizing your filing system this way is that it can always be further subdivided and organized if you need to. This grisly, nightmare-inducing episode about an inbred family of killers was so terrifying and controversial that Fox famously decreed that it would never be aired again after its initial broadcast prompted a flood of complaints from concerned viewers. I could stop at that as a reason to watch, but there's more. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site. -

Deleuze and Queer Theory

Chapter 8 Unnatural Alliances Patricia MacCormack Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari use as a key example of becomings becoming-animal. Becoming-animal involves both a repudiation of the individual for the multiple and the human as the zenith of evolution for a traversal or involution across the speciesist plane of consistency. Deleuze and Guattari delineate the Oedipal animal, the pack animal and the demonic hybridisation of animal, human and imperceptible becom- ings. Various commentators have critiqued and celebrated Deleuze and Guattari’s call to becoming-woman. In his taxonomy of living things Aristotle places women at the intersection of animal and human, so becoming-animal as interstices raises urgent feminist issues as well as addressing animal rights and alterity through becoming-animal. This chapter will invoke questions such as ‘how do we negotiate becoming- animal beyond metaphor?’, ‘what risks and which ethics are fore- grounded that make becoming-animal an important political project?’ and, most importantly, because becoming-animal is a queer trajectory of desire, ‘how does the humanimal desire?’ Anthropomorphism can go either up or down, humanising either the deity or animals, but if the vertical distance is closed in any way, i.e. between God and humans or humans and animals, many are disconcerted. (Adams 1995: 180) For on the one hand, the relationships between animals are the object not only of science but also of dreams, symbolism, art and poetry, practice and practical use. And on the other hand, the relationships between animals are bound up with the relations between man and animal, man and woman, man and child, man and elements, man and the physical and microphysical universe. -

Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in <Em>Detroit: Become

Human-Machine Communication Volume 2, 2021 https://doi.org/10.30658/hmc.2.7 Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in Detroit: Become Human and the Implications for Human- Machine Communication Marco Dehnert1 and Rebecca B. Leach1 1 The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA Abstract In human-machine communication (HMC), machines are communicative subjects in the creation of meaning. The Computers are Social Actors and constructivist approaches to HMC postulate that humans communicate with machines as if they were people. From this perspective, communication is understood as heavily scripted where humans mind- lessly apply human-to-human scripts in HMC. We argue that a critical approach to com- munication scripts reveals how humans may rely on ableism as a means of sense-making in their relationships with machines. Using the choose-your-own-adventure game Detroit: Become Human as a case study, we demonstrate (a) how ableist communication scripts ren- der machines as both less-than-human and superhuman and (b) how such scripts manifest in control and cyborg anxiety. We conclude with theoretical and design implications for rescripting ableist communication scripts. Keywords: human-machine communication, ableism, control, cyborg anxiety, Computers are Social Actors (CASA) Introduction Human-Machine Communication (HMC) refers to both a new area of research and concept within communication, defined as “the creation of meaning among humans and machines” (Guzman, 2018, p. 1; Fortunati & Edwards, 2020). HMC invites a shift in perspective where CONTACT Marco Dehnert • The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication • Arizona State University • P.O. Box 871205 • Tempe, AZ 85287-1205, USA • [email protected] ISSN 2638-602X (print)/ISSN 2638-6038 (online) www.hmcjournal.com Copyright 2021 Authors. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

To Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! December 3 - 9, 2020 Sample sale: INSIDE: Offering: 1/2 off Hydrafacials Venus Legacy What’s new on • Treatments Netflix, Hulu & • BOTOX Call for details Amazon Prime • DYSPORT Pages 3, 17 & 22 • RF Microneedling • Body Contouring • B12 Complex • Lipolean Injections • Colorscience Products • Alastin Skincare Judge him if you must: Bryan Cranston Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 plays a troubled ‘Your Honor’ www.SkinnyJax.comwww.SkinnyJax.com Bryan Cranston stars in the Showtime drama series “Your Honor,” premiering Sunday. 1361 13th Ave., Ste.1 x140 5” ad Jacksonville Beach NowTOP 7 is REASONS a great timeTO LIST to YOUR HOMEIt will WITH provide KATHLEEN your home: FLORYAN List Your Home for Sale • YOUComplimentary ALWAYS coverage RECEIVE: while the home is listed 1) MY UNDIVIDED ATTENTION – • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT becauseno delegating buyers toprefer a “team to purchase member” a Broker Associate home2) A that FREE a HOMEseller stands SELLER behind WARRANTY • whileReduced Listed post-sale for Sale liability with [email protected] UNDER CONTRACT - DAY 1 ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! 3) A FREE IN-HOME STAGING https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com PROFESSIONAL Evaluation BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan 4) ACCESS to my Preferred Professional America’s Preferred Services List Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! 5) AHome 75 Point SELLERS Warranty CHECKLIST for for Preparing Your Home for Sale 6) ALWAYSyour Professionalhome when Photography we put– 3D, Drone, Floor Plans & More 7) Ait Comprehensive on the market. -

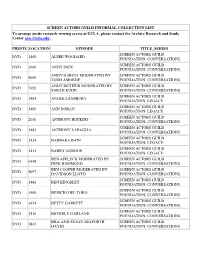

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS -

Agustín Fuentes Department of Anthropology, 123 Aaron Burr Hall, Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544 Email: [email protected]

Agustín Fuentes Department of Anthropology, 123 Aaron Burr Hall, Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544 email: [email protected] EDUCATION: 1994 Ph.D. Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 1991 M.A. Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 1989 B.A. Anthropology and Zoology, University of California, Berkeley ACADEMIC POSITIONS: 2020-present Professor, Department of Anthropology, Princeton University 2017-2020 The Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C., Professor of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2013-2020 Chair, Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2008-2020 Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2008-2011 Director, Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, University of Notre Dame 2005-2008 Nancy O’Neill Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2004-2008 Flatley Director, Office for Undergraduate and Post-Baccalaureate Fellowships, University of Notre Dame 2002-2008 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2000-2002 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University 1999-2002 Director, Primate Behavior and Ecology Bachelor of Science Program, Interdisciplinary Major-Departments of Anthropology, Biological Sciences and Psychology, Central Washington University 1998-2002 Graduate Faculty, Department of Psychology and Resource Management Master’s Program, Central Washington University 1996-2000 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University 1995-1996 Lecturer, -

Hallmark Collection

Hallmark Collection 20000 Leagues Under The Sea In 1867, Professor Aronnax (Richard Crenna), renowned marine biologist, is summoned by the Navy to identify the mysterious sea creature that disabled the steamship Scotia in die North Atlantic. He agrees to undertake an expedition. His daughter, Sophie (Julie Cox), also a brilliant marine biologist, disguised as a man, comes as her father's assistant. On ship, she becomes smitten with harpoonist Ned Land (Paul Gross). At night, the shimmering green sea beast is spotted. When Ned tries to spear it, the monster rams their ship. Aronnax, Sophie and Ned are thrown overboard. Floundering, they cling to a huge hull which rises from the deeps. The "sea beast" is a sleek futuristic submarine, commanded by Captain Nemo. He invites them aboard, but warns if they enter the Nautilus, they will not be free to leave. The submarine is a marvel of technology, with electricity harnessed for use on board. Nemo provides his guests diving suits equipped with oxygen for exploration of die dazzling undersea world. Aronnax learns Nemo was destined to be the king to lead his people into the modern scientific world, but was forced from his land by enemies. Now, he is hoping to halt shipping between the United States and Europe as a way of regaining his throne. Ned makes several escape attempts, but Sophie and her father find the opportunities for scientific study too great to leave. Sophie rejects Nemo's marriage proposal calling him selfish. He shows his generosity, revealing gold bars he will drop near his former country for pearl divers to find and use to help the unfortunate. -

Towncrier-Dec2018.Pdf

2 December 13, 2018 THE TOWN CRIER Cover Story Paul Revere Middle School ’Tis the Season of Giving Patriots are giving back to their community by lending out helping hands to those in need. start of Revere’s season of giv- By ALEXA DREYFUS es that Patriots were able to win Positive Chalk on Nov 30. This and JULIA MUSUMECI ing back. were gift cards, and the winners was a great opportunity for Pa- The next week was Hallow- were Johnny Harvey and Dan- triots to write positive messag- As the weather gets colder, een, which everyone knows is ielle Efron. es, outside of the X building, to Revere gets warmer. Patriots filled with tons of candy. Af- Right after Halloween, the refugees who do not get a good lend helping hands all around ter Halloween, there is always Community Service Club col- education. To host the event, the campus, and spread the holiday leftover candy that gets thrown lected old crayons, that were not Community Service Club had cheer. There were many oppor- away. So, the Community Ser- being used anymore. The cray- snack sales from Nov 5 to Nov tunities for Patriots to partici- vice Club organized Operation ons were donated to a school 9 and the proceeds went to Cis- pate in helping others, led by the Gratitude where they collected that could not afford to supply arva Refugee Learning Center, Community Service Club, Lead- all of that extra candy that would their classrooms with the same which helps out refugees in Syr- ership and even on their own. -

DARK CITY HIGH the High School Noir of Brick and Veronica Mars Jason A

DARK CITY HIGH THE HIGH SCHOOL NOIR OF BRICK AND VERONICA MARS Jason A. Ney ackstabbing, adultery, blackmail, robbery, corruption, and murder—you’ll find them all here, in a place where no vice is in short supply. You want drugs? Done. Dames? They’re a dime a dozen. But stay on your toes because they’ll take you for all you’re worth. Everyone is work- ing an angle, looking out for number one. Your friend could become your enemy, and if the circumstances are right, your enemy could just as easily become your friend. Alliances are as unpredictable and shifty as a career criminal’s moral compass. Is all this the world of 1940’s and 50’s film noir? Absolutely. But, tures like the Glenn Ford vehicle The Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Bas two recent works—the television show Veronica Mars (2004- melodramas like James Dean’s first feature,Rebel Without a Cause 2007) and the filmBrick (2005)—convincingly argue, it is also the (1955). But a noir film from the years of the typically accepted noir world of the contemporary American high school. cycle (1940-1958) populated primarily by teenagers and set inside a That film noir didn’t extend its seductive, deadly reach into the high school simply does not exist. Perhaps noir didn’t make it all the high schools of the forties and fifties is somewhat surprising, given way into the halls of adolescent learning because adults still wanted how much filmmakers danced around the edges of what we now to believe that the teens of their time retained an element of their call noir when crafting darker stories about teens gone bad.