Deleuze and Queer Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in <Em>Detroit: Become

Human-Machine Communication Volume 2, 2021 https://doi.org/10.30658/hmc.2.7 Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in Detroit: Become Human and the Implications for Human- Machine Communication Marco Dehnert1 and Rebecca B. Leach1 1 The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA Abstract In human-machine communication (HMC), machines are communicative subjects in the creation of meaning. The Computers are Social Actors and constructivist approaches to HMC postulate that humans communicate with machines as if they were people. From this perspective, communication is understood as heavily scripted where humans mind- lessly apply human-to-human scripts in HMC. We argue that a critical approach to com- munication scripts reveals how humans may rely on ableism as a means of sense-making in their relationships with machines. Using the choose-your-own-adventure game Detroit: Become Human as a case study, we demonstrate (a) how ableist communication scripts ren- der machines as both less-than-human and superhuman and (b) how such scripts manifest in control and cyborg anxiety. We conclude with theoretical and design implications for rescripting ableist communication scripts. Keywords: human-machine communication, ableism, control, cyborg anxiety, Computers are Social Actors (CASA) Introduction Human-Machine Communication (HMC) refers to both a new area of research and concept within communication, defined as “the creation of meaning among humans and machines” (Guzman, 2018, p. 1; Fortunati & Edwards, 2020). HMC invites a shift in perspective where CONTACT Marco Dehnert • The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication • Arizona State University • P.O. Box 871205 • Tempe, AZ 85287-1205, USA • [email protected] ISSN 2638-602X (print)/ISSN 2638-6038 (online) www.hmcjournal.com Copyright 2021 Authors. -

Agustín Fuentes Department of Anthropology, 123 Aaron Burr Hall, Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544 Email: [email protected]

Agustín Fuentes Department of Anthropology, 123 Aaron Burr Hall, Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544 email: [email protected] EDUCATION: 1994 Ph.D. Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 1991 M.A. Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 1989 B.A. Anthropology and Zoology, University of California, Berkeley ACADEMIC POSITIONS: 2020-present Professor, Department of Anthropology, Princeton University 2017-2020 The Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C., Professor of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2013-2020 Chair, Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2008-2020 Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2008-2011 Director, Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, University of Notre Dame 2005-2008 Nancy O’Neill Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2004-2008 Flatley Director, Office for Undergraduate and Post-Baccalaureate Fellowships, University of Notre Dame 2002-2008 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame 2000-2002 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University 1999-2002 Director, Primate Behavior and Ecology Bachelor of Science Program, Interdisciplinary Major-Departments of Anthropology, Biological Sciences and Psychology, Central Washington University 1998-2002 Graduate Faculty, Department of Psychology and Resource Management Master’s Program, Central Washington University 1996-2000 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University 1995-1996 Lecturer, -

Of Rats and Men

Hugvísindasvið Of Rats and Men How Willard Exemplifies the Fallacy in Polarized Understandings of the Categories of Man and Animal Ritgerð til BA-prófs í kvikmyndafræði Salvör Bergmann Maí 2015 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Kvikmyndafræði Of Rats and Men How Willard Exemplifies the Fallacy in Polarized Understandings of the Categories of Man and Animal Ritgerð til BA-prófs í kvikmyndafræði Salvör Bergmann Kt.: 050390-2849 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnar Theodór Eggertsson Maí 2015 Extract This essay provides an in-depth analysis of Glen Morgan’s 2003 film Willard in relation to an exploration of the issue of polarities, in particular those that separate man and animal. To analyse how the film not only displays said polarities, but subsequently showcases them as residing in fallacy, the categories of man and animal must at first be somewhat adhered to, where the human and animal characters of the film are recognized as originally residing in their separate spheres. It is then scrutinized how those characters exit these spheres, as well as how the spheres themselves seem to hybridize and intermingle. The essay consists of five segments; a foreword, three theoretical and analytical chapters, and a conclusion. The first chapter, “Man becomes Animal”, introduces Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s hypothesis of “becoming-animal” as a recurring focal point of reference throughout the analysis. It also explores film critic Robin Wood’s basic formula of horror in relation to the effect of a man and an animal being doubles. In addition of making use of animal studies alongside general film studies, the essay also utilizes studies of humanistic geography, as the chapter also includes Chris Wilbert’s workings with philosopher Karen Barad’s term “intra-action”. -

Morton Boyer

Timothy Dominic Morton Boyer HYPOSUBJECTS ON BECOMING HUMAN timothy morton / dominic boyer their relations & companions hyposubjects on becoming human CCC2 Irreversibility Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The second phase of ‘the Anthropocene,’ takes hold as tipping points speculated over in ‘Anthropocene 1.0’ click into place to retire the speculative bubble of “Anthropocene Talk”. Temporalities are dispersed, the memes of ‘globalization’ revoked. A broad drift into a de facto era of managed extinction events dawns. With this acceleration from the speculative into the material orders, a factor without a means of expression emerges: climate panic. timothy morton / dominic boyer their relations & companions hyposubjects on becoming human OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS London 2021 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2021 Copyright © 2021 timothy morton / dominic boyer Freely available at: http://openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/hyposubjects This is an open access book, licensed under Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy their work so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. No permission is required from the authors or the publisher. Statutory fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Read more about the license at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 Cover Art, figures, and other media included with this book may be under different copyright restrictions. Print ISBN 978-1-78542-096-2 PDF ISBN 978-1-78542-095-5 eBook ISBN 978-1-78542-097-9 OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS Open Humanities Press is an international, scholar-led open access publishing collective whose mission is to make leading works of contemporary critical thought freely available worldwide. -

Becoming Human: How Evolution Made Us

BECOMING HUMAN: HOW EVOLUTION MADE US Greg Downey BECOMING HUMAN: HOW EVOLUTION MADE US Greg Downey Published by Enculture Press Smashwords edition Copyright 2013 Greg Downey Published by Enculture Press, Australia PO Box 40, Berry, NSW 2535, Australia ISBN: 978-1-925082-01-2 Smashwords edition First edition 2013 Smashwords Edition, License Notes Thank you for downloading this free ebook. You are welcome to share it with your friends. This book may be reproduced, copied and distributed for non-commercial purposes, provided the book remains in its complete original form. If you enjoyed this book, please return to Smashwords.com to discover other works by this author. Thank you for your support. Table of Contents Open2Study Acknowledgments Preface Chapter 1: Traces Chapter 2: Darwin Chapter 3: Sex Chapter 4: Brains Photo credits Glossary About the Author Enculture Press ~~~~~~~~ This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/. For more information on Creative Commons licenses, visit CreativeCommons.org. Please contact Greg Downey for information on licensing: [email protected] This ebook is distributed free through the support of Smashwords, Open Universities Australia and Enculture Press. The text and resources accompany the Open2Study class, ‘Becoming Human: Anthropology.’ Open2Study Free online study for everyone! The Becoming Human: How Evolution Made UseBook is an ideal companion to the free online subject Becoming Human: Anthropology - presented by Greg Downey and offered by Open2Study. In Becoming Human: Anthropology, you can explore how evolution works and how variation arises. -

Becoming Human

10 BECOMING HUMAN In which we begin a fast-forward look at the human journey from tree-dwellers to moonwalkers and the potential expansion of Gaia into space. Our evolutionary journey over the last 30 million years shows clearly our biological origin and that we are part of Gaia. Insignificant at first, we have made up for that in the last 500,000 years. Along our timeline we look for the characteristics that make us human: adaptability, tool use, intelligence – and empathy. These do not stand outside of biology but are part of it, supplemented by our own social evolutionary future. It has already been remarked that being human is another way of being a fish. Not a flat, bottom-dwelling fish, but a goldfish, say. Everyone is familiar with a goldfish. It is an excellent swimmer, swimming with lateral flexures of a muscular body shaped like an aeroplane fuselage. It has pectoral and pelvic fins to provide steering and stability. Its gill slits allow a continuous respiratory flow over the gills as it moves forward, and its swim bladder gives it buoyancy so that it can ‘hover’ at different depths. This general design first appeared, in its basics, about 500 million years ago, and today, with a bit of pushing and pulling, it is a template that fits all animals with backbones (see Shubin 2008 for an excellent account of this process). Goldfish and humans probably last shared an ancestor millions of years ago. Yet we still carry with us the signs that betray the fact that evolution, while often creating novelty, also tinkers with what has gone before. -

Cultural Representations of the Transformative Body in Young Adult Multi-Volume Vampire Fiction, 2000- 2010

Cultural Representations of the Transformative Body in Young Adult Multi-Volume Vampire Fiction, 2000- 2010 J. M. Kubiesa A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2021 University of Worcester Cultural Representations of the Transformative Body in Young Adult Multi-Volume Vampire Fiction, 2000-2010 Jane M. Kubiesa Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………….....6 Abbreviations List……………………………………………………......….......8 Introduction: The Young Adult Vampire Revolution……………………….…..9 1. Cultural Construction of the Young Adult………………………………….12 1.1 Consumerism and Youth Consumption……………………………….15 1.2 Consuming the YA Vampire………………………………………….16 2. Contextualising the Vampire…………………………….…………………..4 3. Vampiric Evolution: From Revenant to Teen Idol…………………………20 4. Embodying the YA “Neoteric Vampire”……………………………...........28 5. Thesis Methodology………………………………………………………..24 Chapter One: Children of the Night: Adolescent Becomings in Evernight……35 1. Introduction: Vampiric Youth…………………….………………………..35 2. Becoming Adolescent: Teen Re-enactment.…………………………….…38 3. Maturation as Metamorphosis…………………….......................................44 3.1 Ambiguous Awakenings and Heterosexual Maturation……………....51 4. Immortal Youth: Vampirising the Other…………………………………...55 4.1 Othering the Child……………………………………….…………...57 4.2 Substituting the Adult………………………………….……………..62 1 Phd Thesis 2021 Cultural Representations of the Transformative Body in Young Adult Multi-Volume Vampire Fiction, 2000-2010 -

Loren Eiseley: Becoming Human Bonnie Heidelmeier Schmidt Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1983 Loren Eiseley: becoming human Bonnie Heidelmeier Schmidt Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Schmidt, Bonnie Heidelmeier, "Loren Eiseley: becoming human" (1983). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14360. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14360 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Loren Eiseley: Becoming human by Bonnie Heidelmeier Schmidt A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Approved: Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1983 INTRODUCTION Odysseus* passage through the haunted waters of the eastern Mediterranean symbolizes, at the start of the Western intellectual tradition, the sufferings that the universe and his own nature in^wse upon the homeward- yearning man* —Loren Eiseley The Iftiexpected Ifcdverse Loren Eiseley (1907-1977) was a respected author and anthropologist, trained also in geology and paleontology, whose many awards and honors -

Program Booklet

Disney’s February 2 - March 4, 2018 February 25 & March 2 2 Wheelock Family Theatre Disney’s Beauty and the Beast 3 February/March 2018 Dear Friends and Family, A warm welcome to Disney's Beauty and the Beast—our first mainstage production of 2018! We're so delighted that you've decided to be our guests at Wheelock Family Theatre. Whether this is your first or fiftieth time at WFT, you will experience our commitment to professional, accessible, inclusive theatre for all generations. You will also see how much we love doing what we do: bringing people with diverse backgrounds and perspectives together, engaging in a collaborative creative process, collectively exploring human ideas, human dilemmas, human conflicts, and human emotions. Beauty and the Beast is most often considered a love story, a tale of redemption. We believe it is that and more: that it is, in the words of director and WFT co-founder Jane Staab, a story of “becoming human again.” As we watch the gradual flowering of this process onstage, we too experience—together, in real time—the range of emotions that come with being human. This shared experience, this mutual discovery, is at the heart of live theatre. It is a magic that inspires and exhilarates us every time the lights dim and the curtain opens. We hope your time with us will also be magical and exhilarating and that it will inspire you to stay connected with WFT, whether through our productions or education program—or both! Stuart Little opens on April 13 and our inaugural teen academy production, Into the Woods Jr., is slated for May 20. -

Becoming Human Free Download

BECOMING HUMAN FREE DOWNLOAD Jean Vanier | 176 pages | 01 May 1999 | Darton,Longman & Todd Ltd | 9780232523362 | English | London, United Kingdom Being Human Christa wants Becoming Human turn Danny into a better human. The book is filled with encouraging, engaging stories, shared by a Godly man, that teach stupendous life lessons! Crazy Credits. Matt and Becoming Human lure the transforming Christa into the gym's supply cupboard and barricade the door. Among the clues include appeals and missing posters made by Matt's parents, voice messages and videos made by Adam and Christa, and Christa's journal entries. Vanier, help is to understand ourselves so we can see those around us who are too often overlooked. Matt is reluctant to do so, as he has come to enjoy the company of Adam and Christa - being happier than he'd ever been in his lifetime - and the excitement of the investigation. Archived from the original on 16 April Roe lets slip to the trio that Mr. Becoming Human Article Are Neanderthals Human? Sep 29, Nicole rated it really liked it. Company Credits. For even more, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. Frequently Asked Questions Q: Where is their house? Becoming Human Vanier to blame, or the editor or the transfer to Kindle. An experience of God quenches this thirst for the absolute but at the same time, paradoxically, whets it, because this is an experience that can never be total; by necessity, the knowledge of God is always partial. Following events that unfold in the third series of Being Human, vampire Adam Craig Roberts; Young Dracula is at college trying to get himself back on the straight and narrow. -

UNTHINKING MASTERY This Page Intentionally Left Blank UNTHINKING MASTERY

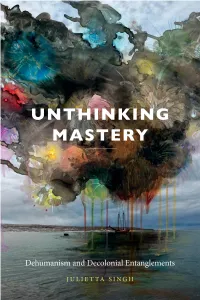

UNTHINKING MASTERY This page intentionally left blank UNTHINKING MASTERY Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements Julietta Singh Duke University Press Durham and London 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro and Gill Sans Std by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Names: Singh, Julietta, [date] author. Title: Unthinking mastery : dehumanism and decolonial entanglements / Julietta Singh. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2017019894 (print) lccn 2017021286 (ebook) isbn 9780822372363 (ebook) isbn 9780822369226 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369394 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Postcolonialism in literature. | Power (Social sciences) in literature. | Coetzee, J. M., 1940– —Criticism and interpretation. | Mahāśvetā Debī, 1926– 2016—Criticism and interpretation. | Sinha, Indra—Criticism and interpretation. | Kincaid, Jamaica—Criticism and interpretation. Classification: lcc pn56.p555 (ebook) | lcc pn56.p555 s55 2017 (print) | ddc 809/.93358—dc23 lc record available at https:// lccn .loc .gov /2017019894 Cover art: Sarah Anne Johnson, Party Boat, 2011. Scratched chromogenic print, photospotting and acrylic inks, gouache and marker, 28 × 42 in. Image courtesy of the artist. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction Reading against Mastery 1 1 Decolonizing Mastery -

Becoming Human

Travelling in the Ark 83 Travelling in the Ark BY HEIKI PECKRUHN With whom are we being human together? With whom are we living together into our potentialities? These questions of community and humanity, central to the L’Arche com- munities, are explored in four books reviewed here. hat does it mean to be human? What must we do to live into our best human potential? In theological and philosophical discussions Wthese questions are often answered by first defining minimum mark- ers of humanity, and then coming up with strategies for developing these qualities in living human beings. In other words, we make a claim about what defines a human being first (made in God’s image, or capable of reason and empathy), and then we muse about what it might look like to pursue the full potential of our humanity (to love and serve God and others, or to use our intellectual and emotional capacities in a moral fashion). Jean Vanier strikingly reframes these questions in Becoming Human (Mah- wah, NJ: Paulist Press, second edition, 2008 [1999], 166 pp., $12.95) comprised of his 1998 Massey Lectures, part of a prestigious radio series commissioned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the University of Toronto. With whom are we being human together? With whom are we living together into our potentialities? Vanier invites us into his personal reflections on becoming human, reflections which center on befriending others, especially those who are marginalized, dehumanized, and excluded. Through living in relationship together we come to discover our common humanity and potential for a good life.