Consequences of Electoral Reforms in Slovakia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newcomers in Politics? the Success of New Political Parties in the Slovak and Czech Republic After 2010?

BALTIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLITICS A Journal of Vytautas Magnus University VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2 (2015) ISSN 2029-0454 Cit.: Baltic Journal of Law & Politics 8:2 (2015): 91–111 http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/bjlp DOI: 10.1515/bjlp-2015-0020 NEWCOMERS IN POLITICS? THE SUCCESS OF NEW POLITICAL PARTIES IN THE SLOVAK AND CZECH REPUBLIC AFTER 2010? Viera Žúborová Associate Professor University of St. Cyril and Methodius, Faculty of Social Sciences (Slovakia) Contact information Address: Namestie Jozefa Herdu 2, 917 01 Trnava, Slovakia Phone: +421 33 55 65 302 E-mail address: [email protected] Received: September 25, 2015; reviews: 2; accepted: December 28, 2015. ABSTRACT The last election in the Slovak and Czech Republic was special. It not only took place before the official electoral period (pre-elections), but new political parties were “again” successful. The article focuses not only on both elections in the last two years in a comparative perspective, but it analyses the opportunity structure of success as well, including types of new political parties (according to Lucardie). The article seeks to answer the question: why are new political parties electorally successful, able to break into parliament and even become part of a coalition government? We assume that the emergence and success of new political parties in both countries relied on the ability to promote “old” ideas in a new fashion, colloquially referred to as “new suits” or “old” ideological flows in new breeze. KEYWORDS New political parties, prophetic parties, purifiers parties, prolocutors parties - 10.1515/bjlp-2015-0020 Downloaded from De Gruyter Online at 09/13/2016 12:19:48AM via free access BALTIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLITICS ISSN 2029-0454 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2 2015 INTRODUCTION The research on the electoral success of new parties in Central and Eastern Europe still lacks depth. -

MODERN ANTISEMITISM in the VISEGRÁD COUNTRIES Edited By: Ildikó Barna and Anikó Félix

MODERN ANTISEMITISM IN THE VISEGRÁD COUNTRIES Edited by: Ildikó Barna and Anikó Félix First published 2017 By the Tom Lantos Institute 1016 Budapest, Bérc utca 13-15. Supported by 2017 Tom Lantos Institute All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN 978-615-80159-4-3 Peer reviewed by Mark Weitzman Copy edited by Daniel Stephens Printed by Firefly Outdoor Media Kft. The text does not necessarily represent in every detail the collective view of the Tom Lantos Institute. CONTENTS 01 02 Ildikó Barna and Anikó Félix CONTRIBUTORS 6 INTRODUCTION 9 03 Veronika Šternová 04 Ildikó Barna THE CZECH REPUBLIC 19 HUNGARY 47 I. BACKGROUND 20 I. BACKGROUND 48 II. ANTISEMITISM: II. ANTISEMITISM: ACTORS AND MANIFESTATIONS 27 ACTORS AND MANIFESTATIONS 57 III. CONCLUSIONS 43 III. CONCLUSIONS 74 05 Rafal Pankowski 06 Grigorij Mesežnikov POLAND 79 SLOVAKIA 105 I. BACKGROUND 80 I. BACKGROUND 106 II. ANTISEMITISM: II. ANTISEMITISM: ACTORS AND MANIFESTATIONS 88 ACTORS AND MANIFESTATIONS 111 III. CONCLUSIONS 102 III. CONCLUSIONS 126 The Tom Lantos Institute (TLI) is its transmission to younger gener- an independent human and minori- ations. Working with local commu- ty rights organization with a par- nities to explore and educate Jewish ticular focus on Jewish and Roma histories contributes to countering communities, Hungarian minori- antisemitism. The research of con- ties, and other ethnic or national, temporary forms of antisemitism is linguistic and religious minori- a flagship project of the Institute. -

List of Panelists

Institute of European Democrats in cooperation with Young Europeans (Mladí Európania) and with the financial support of the European Parliament Schengen at Risk: Can We Keep the Freedom of Movement? International Conference 13th May 2016 Falkensteiner Hotel, Bratislava, Slovakia Panellists First session: “The Visegrad Group and the Migration impasse: Schengen at stake?” Jana Vnuková, Head of European Union Law Unit of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic. In past, she was working at the various positions in the Ministry of Justice of the Slovak Republic, including Deputy Director General of the International and European Law and Director of Human Rights Division. She was also the Chair of the Committee for the Development of Human Rights of the Council of Europe. Currently, she is also the external lecturer at the Slovak Judicial Academy where she lectures domestic seminars on European law and judicial cooperation. Zsuzsanna Szelényi, Member of the Hungarian Parliament, Együtt Pártja, Hungary. Mrs Szelényi has held several political responsibilities in Hungary since the transition to democracy. Furthermore, Mrs Szelényi worked for the Council of Europe from 1996 to 2010, as Deputy Director of the European Youth Centre Budapest. She headed the Roma Education Fund in 2010. She worked as an International Development Consultant in the Balkans and North Africa since 2011. IED – ASBL - rue de l’Industrie, 4 – B 1000 Brussels - tel 02.2130010 – www.iedonline.eu “With the financial support of the European Parliament” Václav Nekvapil, CEC Government Relations’ Managing Director, Czech Republic, obtained his PhD in politics from Charles University in 2013. -

The Migration Crisis and the European Union: the Effects of the Syrian Refugee Crisis to the European Union

The Migration Crisis and the European Union: The Effects of the Syrian Refugee Crisis to the European Union Diane Faie O. Valenzuela 2014-05015 Political Science 172, MHB Professor Carl Marc Ramota Abstract In this paper, I will be discussing about the Syrian refugee crisis in the European Union. The Syrian refugee crisis, which is currently being experienced in European countries is said to be the one of the largest forced migrations since World War II. More and more refugees are heading towards European countries which are renowned to have good living conditions despite the perilous journey wherein thousands have died and face very inhumane conditions in getting to their destination. Because of this, the European Union has begun to undergo measures to help control the influx of refugees, most of which are at the cost of these refugees' safety. Keywords: Syrian Refugees, Migration Crisis, European Countries, European Union, Syrian Civil War The Syrian Conflict In February 2011, there were protests which erupted in the Southern city of Dar’a as a response to the apprehension of 15 middle school aged boys who had spray painted the common Arab slogan of the protests which bears pro-democracy slogans, wanting the ouster of the Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad (Abboud, 2016). The protests at first simply wanted the Government to release the boys including political prisoners, but later began to evolve towards anti-regime tones which targeted the emergency laws, poor socio economic conditions, corruption, police brutality, and indiscriminate detention (Abboud, 2016). Dar’a began to experience the first protests of the Syrian uprising which was then called ‘Day of Anger’ on February 17, 2011 (Abboud, 2016). -

A Pdf to See This Article As It Appears in Print

Slovak World Congress (SWC) and Canadian Slovak League (CSL) journalists finally exposed his Nazi past.14 Created While Tiso While Tiso was executed for war and led by Nazi was executed for war crimes, crimes in 1947 by Czechoslovakia’s elect- collaborators and ed communist government, the SWC and their allies—the Toronto- two of his worst cronies, Jozef CSL hailed him as a national hero. On the based SWC and CSL— Kirschbaum and 50th anniversary of his death, CSL Toronto enjoyed many decades of Ferdinand Dur- held a Sunday church event to honour him. Cold-War support from the The day cansky, escaped Jozef Kirschbaum gave the commemorative Canadian government and after he met their trials. Given speech. The CSL raised funds to help buy corporate media, which Tiso’s home for use as a museum to exalt Hitler, Jozef safe haven by shared their toxic, his memory. Involved in that project were Tiso declared Canada’s Liberal anti-Red social various leaders including CSL president Ste- a “free” Slovakia. government, they psychosis phen Kovacic,15 who represented the CSL President Tiso’s Nazi helped to found at ABN-Canada’s 1986 conference. At that regime deported about and lead both the event featuring CIA-backed Nicaraguan and 75,000 Jews to death camps. SWC and CSL. Afghan terror groups, as well as many oth- Such myths of Nazi Slovakian inno- ers created and led by Nazi collaborators, cence have long been spread by key Cana- the CSL’s Kovacic said: bit.ly/HitlerTiso dian academics. As a history professor in It is my honour, by this presentation to he Slovak World Congress (SWC) Montreal and Toronto, and co-founder of the join the common fight of the enslaved was founded in Toronto in 1971 by University of Ottawa’s Chair in Slovak His- nations in Northern, Central and Eastern tory, Kirschbaum himself led the cover up. -

FMA Visit to Bratislava in Context of Slovak Presidency

2016 FMA Visit to Bratislava in context of Slovak Presidency 7- 8 NOVEMBER 2016 FMA Secretariat Office JAN 2Q73 European Parliament B-1047 Brussels Tel: +322.284.07.03 Fax: +332.284.09.89 E-mail: [email protected] Elisabetta FONCK Mobile phone : +32.473.646.746746 INDEX I. The Slovak EU Presidency 2016 ....................................................................................... 5 1. Priority Dossiers under the Slovak EU Council Presidency ................................... 7 2. Programme of the Presidency ........................................................................... 17 3. Slovak Presidency priorities discussed in parliamentary committees................. 53 4. Contributions of the LV COSAC........................................................................... 57 II. Political system in Slovakia .......................................................................................... 63 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 65 2. National Council and Parliamentary elections’ result ........................................ 67 2.1 NDI 2016. Parliamentary elections result ............................................. 79 2.2 The 2016 elections in Slovakia: a shock ............................................... 85 2.3 OSCE/ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Final Report ...................... 87 III. Economy in Slovakia ................................................................................................ -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN SLOVAKIA 29th February 2020 European Can Robert Fico’s Direction- Elections Monitor Social Democracy remain in office in Slovakia? Corinne Deloy Analysis Slovaks are being called to the polls on 29 February to the resignation in March 2018 of Prime Minister Robert renew the 150 members of the National Council of the Fico, two ministers and the police chief. Republic (Narodna rada Slovenskej republiky), the only house of parliament. This election is an «important test The vote comes at the same time as the trial of for the country,» said political analyst Tomas Koziak. businessman Marian Kocner, who was arrested and «Will the electorate vote for parties that try to limit imprisoned in October 2018 for the double murder of democracy, compromise democratic ideas, or will they Kuciak and Kusnirova. Kocner, is also being prosecuted for turn to parties that oppose such practices?” The poll is dubious financial transactions and tax evasion, together taking place in an atmosphere of protest against the with three other people, the two killers, one of whom is authorities in power - and in particular the political class a former soldier, who has confessed to the murder, as - accused of corruption on the one hand, and the threat well as Alena Szuzsova, one of the businessman’s loyal of a vote in favour of the far-right nationalists united in associates, who are accused of acting as intermediaries. the People’s Party-Our Slovakia (LSNS) led by Marian The defendants face sentences ranging from 25 years to Kotleba on the other. This has also led to the creation life imprisonment. -

La Revue | 1/2021

#01 Populisme La revue | 1/2021 Le premier numéro de Populisme reprend uniquement et exclusivement des articles consacrés au populisme déjà publiés ailleurs et dont les auteurs ont conservé les droits. Il valorise des articles plus anciens mais mis à jour partiellement ou totalement en 2021 ; des articles plus anciens inchangés mais précédés d’un texte introductif qui remet dans le contexte actuel l’article publié par le passé, par exemple en insistant sur les évolutions qui ont suivi la publication. Ce premier numéro de Populisme valorise aussi des articles publiés dans une langue mais inédit dans une autre à l’issue d’une traduction. À travers ces trois formules, ce numéro de lancement vise à donner une deuxième vie à des contributions plus anciennes. Populisme La revue | 1/2021 Presses Universitaires de Liège Tél. : +32 (4) 366 50 22 Courriel : [email protected] Place de La République française, 41 Bât. O1 (7e étage) 4000 Liège – Belgium Site : www.presses.uliege.be © 2021 Tous droits de reproduction, d’adaptation et de traduction réservés pour tous pays Maquette de couverture et mise en page : Thierry MOZDZIEJ Populisme La revue | 1/2021 Presses Universitaires de Liège à PROPOS La revue Populisme est une initiative du Professeur Jérôme Jamin et de son centre d’études Démocratie en partenariat avec les Presses Universitaires de Liège. Multidisciplinaire et interdisciplinaire par essence, elle propose deux nu- méros thématiques par an. Direction - Jérôme Jamin Secrétariat de rédaction - François Debras Mise en page - Thierry Mozdziej -

Disinformation, Euroskepticism and Pro-Russian Parties in Eastern Europe

disinformation, Euroskepticism and pro-Russian Parties in Eastern Europe Maria Snegovaya Disinformation, Euroskepticism and pro-Russian Parties in Eastern Europe 1 Disinformation, Euroskepticism and pro-Russian Parties in Eastern Europe FREE RUSSIA FOUNDATION 20 21 Free Russia Foundation Author Maria Snegovaya Editor-in-Chief Anton Shekhovtsov Proofreading Courtney Dobson, Bluebearediting Layout Free Russia Designs CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 ANTI-EU SENTIMENT AS RUSSIA’S 7 GEOPOLITICAL TOOL CLASSIFYING PRO-RUSSIAN PARTIES 8 VULNERABLE GROUPS AND HYPOTHESIS 11 RESEARCH DESIGN 13 FINDINGS 15 CONCLUSION 19 REFERENCES 20 ABOUT AUTHOR Maria Snegovaya Postdoctoral Fellow at Virginia Tech (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University), Visiting Fellow at George Washington Uni- versity ABSTRACT What social groups support pro-Russian parties in Eastern Europe? This paper demonstrates that pro-Russian parties in Eastern Europe tend to have electorates with significantly more Euroskeptic attitudes than voter bases of mainstream parties. Importantly, support for pro-Russian parties is not related to an individual’s ideological (right or left) leanings. Because of their Euroskeptic attitudes, social groups supporting pro-Russian parties are far more susceptible to disinformation and, in particular, the anti-EU narratives spread by the Kremlin. These findings explain the endorsement of pro-Russian narratives and social attitudes which are indirectly favorable to the Kremlin by political leaders whose electorates harbor anti-Western sympathies. It also sheds light on the nature of Russia’s information opera- tions that seem to be opportunistic rather than ideological in nature, but also limited in scope by the structural conditions in targeted societies. Disinformation, Euroskepticism and pro-Russian Parties in Eastern Europe 5 INTRODUCTION In recent years, accumulating evidence has exposed the Kremlin’s active measures campaign in Europe, which consists of a set of efforts to weaken European democracies. -

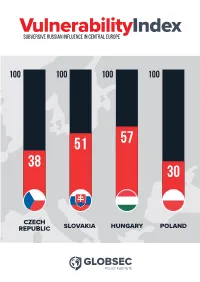

Vulnerabilityindex

VulnerabilitySUBVERSIVE RUSSIAN INFLUENCE IN CENTRAL EUROPE Index 100 100 100 100 51 57 38 30 CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA HUNGARY POLAND Credits Globsec Policy Institute, Klariská 14, Bratislava, Slovakia www.globsec.org GLOBSEC Policy Institute (formerly the Central European Policy Institute) carries out research, analytical and communication activities related to impact of strategic communication and propaganda aimed at changing the perception and attitudes of the general population in Central European countries. Authors: Daniel Milo, Senior Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Policy Institute Katarína Klingová, Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Policy Institute With contributions from: Kinga Brudzinska (GLOBSEC Policy Institute), Jakub Janda, Veronika Víchová (European Values, Czech Republic), Csaba Molnár, Bulcsu Hunyadi (Political Capital Institute, Hungary), Andriy Korniychuk, Łukasz Wenerski (Institute of Public Affairs, Poland) Layout: Peter Mandík, GLOBSEC This publication and research was supported by the National Endowment for Democracy. © GLOBSEC Policy Institute 2017 The GLOBSEC Policy Institute and the National Endowment for Democracy assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. Sole responsibility lies with the authors of this publication. Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Country Overview 7 Methodology 9 Thematic Overview 10 1. Public Perception 10 2. Political Landscape 15 3. Media 22 4. State Countermeasures 27 5. Civil Society 32 Best Practices 38 Vulnerability Index Executive Summary CZECH REPUBLIC: 38 POLAND: 30 PUBLIC PERCEPTION 36 20 POLITICAL LANDSCAPE 47 28 MEDIA 34 35 STATE COUNTERMEASURES 23 33 CIVIL SOCIETY 40 53 SLOVAKIA: 51 53 HUNGARY: 57 50 31 40 78 78 60 39 80 45 The Visegrad group countries in Central Europe (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia – V4) are often perceived as a regional bloc of nations sharing similar aspirations, aims and challenges. -

State Reactions on Radical Movements in Slovakia This Study Aims to Map

State reactions on radical movements in Slovakia This study aims to map State reactions to radical movements in the Slovak republic since 1990. When we refer to State, we refer to all State, self-government and judicial bodies: central government and national parliament, regional governments, local governments, police and courts. 1990 – 2003: no public activities, no media attention, no specific state policy The first radical movements and ideas penetrated Slovakia in the late 1980s years of 20 th century and especially after the fall of communism in 1989. These movements evolved from an underground music scene whose foundations were based on a mixture of music and racist ideology. During the early period of this extremist ‘scene’, the regular targets of hatred were Slovakia’s ethnic minority groups such as Roma, Czech nationals and Jews. After break-up of Czechoslovakia in 1993, the situation changed, in the sense that Czechs ceased to be considered enemies. The radical movements began to find their heroes in Slovak history. Between 1939 and 1945, the leaders of the Slovak republic offered a unified ideology of racism and nationalism. The tomb of Jozef Tiso, who was president of the Slovak republic during the Second World War, became the site for regular meetings for extreme Right-wing groups, particularly on 14 th of March each year (the anniversary of 1939 declaration of the Slovak republic). An organisation named Slovensky Narodny Front (Slovak National Front) , made up of ‘skinheads’, is one such group. But the Ministry of Interior prohibited the registration of this organisation, due primarily to having the word “front” as part of its name (it sounded ‘too militaristic’). -

Investigating Russia's Role and the Kremlin's Interference in the 2019

Investigating Russia’s role and the Kremlin’s interference in the 2019 EP elections Authors Patrik Szicherle Adam Lelonek, Ph.D. Grigorij Mesežnikov Jonas Syrovatka Nikos Štěpánek Budapest May, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 3 Executive summary 3 Policy recommendations on countering the threat and strategic communications 4 Countering disinformation through policies 4 Strategic communications 6 Methodology 7 Introduction 7 What does Russia stand to gain? 8 What factors are helping disinformation to spread? 9 The official Kremlin-backed narratives in the West 11 The encirclement of Russia 12 Euroscepticism 13 Other important pro-Russian narratives 14 Narratives in Hungarian media 15 Euroscepticism in the spotlight: traditional values vs Soros’s multiculturalism 15 Ukraine in the focus 17 The media of perceived national interest and pro-Kremlin portals 18 Slovakia 19 The presidential election and its implications 19 In support of Eurosceptic forces 20 Czech Republic 22 Strong and peaceful Russia, aggressive US 22 EU: a topic of secondary importance 23 Poland 24 Internal political disputes on the EU help information aggressors 24 The West is an aggressor, while Russia is simply defending itself 25 Anti-Semitism used against American and European elites 26 Conclusions 27 Appendix 30 List of local portals under examination 30 References 33 Notes 41 2 Foreword FOREWORD We are thankful for Friedrich Naumann Foundation for its support for the project. We would like to thank our partners, Jonas Syrovatka (CZ), Nikos Štěpánek (CZ), Grigorij Mesežnikov (SK) and Adam Lelonek (PL) for their immense contribution to this paper. We are also grateful to the participants of our workshop on Russian influence in Europe for contributing to this paper with their insightful comments.