Land of the Golden Man, on the Following Pages, Include the Use of All the Pictures on This Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

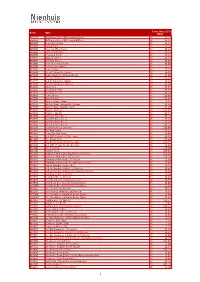

Pricelist Montessori 2015 Koduleht.Pdf

Koolide Varustus OÜ, Puuvilla 19, Tallinn 10314, tel. 6611767, 5516363 www.koolidevarustus.ee e-mail:[email protected] MONTESSORI ÕPPEVAHENDID KOOD NIMETUS HIND koos km-ga Infant Toddler (pages 12 - 31) 040600 Sorting Tray € 48,07 040700 Braiding Board € 39,33 040900 Thread Ring € 33,87 041100 Object Permanence Box With Tray € 66,64 041200 Object Permanence Box With Drawer € 61,18 041900 Imbucare Box With Flip Lid - Knit Ball € 62,27 042000 Imbucare Box With Hinge Lid And Knit Ball € 62,27 042100 Imbucare Box With Large Cylinder € 49,16 042200 Imbucare Box With Small Cylinder € 49,16 042300 Imbucare Box With Cube € 53,53 042400 Imbucare Box With Triangular Prism € 53,53 042500 Imbucare Box With Rectangular Prism € 53,53 042600 Imbucare Box With Flip Lid - 1 Slot € 60,08 042700 Imbucare Box With Flip Lid - 4 Shapes € 60,08 042800 Box With Sliding Lid € 53,53 042900 Imbucare Board With Disc € 56,81 043000 Imbucare Board With Knit Ball € 56,81 043100 Imbucare Peg Box € 74,29 043200 Imbucare Box With Knit Ball € 64,45 043300 Imbucare Box With 3 Colored Knit Balls € 81,93 043500 3D Object Fitting Exercise € 69,92 044100 Single Shape Puzzle Set € 80,84 044200 Multiple Shape Puzzle Set € 87,39 045100 Cubes On Vertical Dowel € 40,42 045200 Discs On Vertical Dowel € 30,59 045300 Discs On Horizontal Dowel € 34,96 045400 Horizontal Dowel Variation - Straight € 39,33 045500 Horizontal Dowel Variation - Serpentine € 48,07 045600 Colored Discs On Colored Dowels € 65,55 045700 Ellipsoids On Small Pegs € 50,25 045800 Three Discs On A -

^Final 2014 Hispanic Heritage Month Elementary Resource 08

1 September 15 – October 15 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section I Hispanic Heritage Month Reference and Resources Legislative History of Hispanic Heritage Month Section II List of Local Museums Section III Florida Hispanic Heritage Timeline Section IV Lesson Plans o Carnival! o It’s All Music o Mapping of South America o Hispanic Heritage (Important Individuals) Section V Activities o Create Your Own Word Search o Famous Hispanics o A Picture Dictionary o Letters to Congressional Hispanic Caucus Section VI Hispanic Heritage Month Suggested Reading List (Florida Department of Education) 3 Hispanic Heritage Month Reference and Resources Elementary September 15 – October 15 5 Hispanic Heritage Month: September 15 – October 15 The following online databases are available through the Broward Enterprise Education Portal (BEEP) http://www.broward.k12.fl.us/it/resources/research.htm The databases highlighted below contain resources, including primary sources/documents, which provide information on Hispanic heritage, history, and notable Hispanics and Latinos. Along with reference content, some of the online databases listed below include lesson plans, multimedia files (photographs, videos, and charts/graphs), activities, worksheets, and answer keys. Contact your library media specialist for username and password. Database Suggested Type of Files Sample Search(es) Search Term(s)* Gale Kids Info Bits Hispanic Americans, Reference articles, magazine articles, Click on the History & Social Studies Click on the link Latinos, Latin America, newspaper articles, maps/flags and Ethnic Groups. Select “Hispanic Americans.” Choose South America, seals, charts & graphs, images the tab titled “Magazines.” Students can read an article Spanish Language, titled "Meet the judge! Sonia Sotomayor is the first Hispanic Heritage Hispanic American justice on the U.S. -

The History of Florida's State Flag the History of Florida's State Flag Robert M

Nova Law Review Volume 18, Issue 2 1994 Article 11 The History of Florida’s State Flag Robert M. Jarvis∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Jarvis: The History of Florida's State Flag The History of Florida's State Flag Robert M. Jarvis* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........ .................. 1037 II. EUROPEAN DISCOVERY AND CONQUEST ........... 1038 III. AMERICAN ACQUISITION AND STATEHOOD ......... 1045 IV. THE CIVIL WAR .......................... 1051 V. RECONSTRUCTION AND THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ..................... 1056 VI. THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ................... 1059 VII. CONCLUSION ............................ 1063 I. INTRODUCTION The Florida Constitution requires the state to have an official flag, and places responsibility for its design on the State Legislature.' Prior to 1900, a number of different flags served as the state's banner. Since 1900, however, the flag has consisted of a white field,2 a red saltire,3 and the * Professor of Law, Nova University. B.A., Northwestern University; J.D., University of Pennsylvania; LL.M., New York University. 1. "The design of the great seal and flag of the state shall be prescribed by law." FLA. CONST. art. If, § 4. Although the constitution mentions only a seal and a flag, the Florida Legislature has designated many other state symbols, including: a state flower (the orange blossom - adopted in 1909); bird (mockingbird - 1927); song ("Old Folks Home" - 1935); tree (sabal palm - 1.953); beverage (orange juice - 1967); shell (horse conch - 1969); gem (moonstone - 1970); marine mammal (manatee - 1975); saltwater mammal (dolphin - 1975); freshwater fish (largemouth bass - 1975); saltwater fish (Atlantic sailfish - 1975); stone (agatized coral - 1979); reptile (alligator - 1987); animal (panther - 1982); soil (Mayakka Fine Sand - 1989); and wildflower (coreopsis - 1991). -

Year 2 Home Learning Activities Complete These Daily Activities

Week: 29th June 2020 Year 2 Home Learning Activities Complete these daily activities. Warm up to learning English Maths Choose from: Choose from: Choose from: https://www.youtube.com/thebodycoachtv https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/dailylessons https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/dailylessons or (Questions) (Measure in grams) https://www.youtube.com/user/CosmicKidsYoga or or Monday https://classroom.thenational.academy/schedule-by-year/year-2/ https://whiterosemaths.com/homelearning/year-2/ (only use if you followed this last week as it follows on) (Measure mass in grams) Choose from: Choose from: Choose from: https://www.youtube.com/thebodycoachtv https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/dailylessons https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/dailylessons or (Counting poems) (Measure in kilograms) https://www.youtube.com/user/CosmicKidsYoga or or Tuesday https://classroom.thenational.academy/schedule-by-year/year-2/ https://whiterosemaths.com/homelearning/year-2/ (only use if you followed this last week as it follows on) (Measure mass in kilograms) Choose from: Choose from: Choose from: https://www.youtube.com/thebodycoachtv https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/dailylessons https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/dailylessons or (Curly caterpillar letters and apostrophes) (Compare volume) https://www.youtube.com/user/CosmicKidsYoga or or https://classroom.thenational.academy/schedule-by-year/year-2/ https://whiterosemaths.com/homelearning/year-2/ Wednesday (only use if you followed this last week as it follows on) (Compare volume Choose from: Choose from: Choose from: https://www.youtube.com/thebodycoachtv -

Collective Difference: the Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Collective Difference: The Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N. Stallings Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC COLLECTIVE DIFFERENCE: THE PAN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF COMPOSERS AND PAN-AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN MUSIC, 1925-1945 By STEPHANIE N. STALLINGS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stephanie N. Stallings All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephanie N. Stallings defended on April 20, 2009. ______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Brewer Committee Member ______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my warmest thanks to my dissertation advisor, Denise Von Glahn. Without her excellent guidance, steadfast moral support, thoughtfulness, and creativity, this dissertation never would have come to fruition. I am also grateful to the rest of my dissertation committee, Charles Brewer, Evan Jones, and Douglass Seaton, for their wisdom. Similarly, each member of the Musicology faculty at Florida State University has provided me with a different model for scholarly excellence in “capital M Musicology.” The FSU Society for Musicology has been a wonderful support system throughout my tenure at Florida State. -

AN ANALYSIS of FLAG CHANGES in LATIN AMERICA Ralph Kelly

Comunicaciones del Congreso Internacional de Vexilología XXI Vexilobaires 2005 CAUDILLOS, COUPS, CONSTITUTIONS AND CHANGES: AN ANALYSIS OF FLAG CHANGES IN LATIN AMERICA Ralph Kelly Abstract: The paper provides a review of historical changes in the design of national flags in Latin America since independence. Despite the perception that their national flags do not change, a number of Latin American countries have changed the design of their national flag since independence, either in minor ways or by adopting a completely new design. Some countries have experienced frequent flag changes in the past and only two Latin American national flags have never changed since independence. The paper undertakes a statistical analysis of the pattern of such changes and their reasons, which can be categorised into eight factors. The paper seeks to explain the past changes of the national flags of Latin America in the context of the unique history of the continent. Many flag changes in the past have been associated with changes of government, but in the past century the national flag is a more significant symbol than contemporary governments. The paper assumes an existing general knowledge of the designs and meaning of Latin American flags. Illustrations include reproductions from some of the major historical flag books of the Nineteenth Century and new re-constructions by the author. Text: The initial impression of Latin American flags is that they do not change. All of the national flags shown in "The Flags of the Americas" issue of The National Geographic -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

The Three Flags of General Belgrano

FAHNEN FLAGS DRAPEAUX (Proceedings of the 15'*’ ICV, Zurich, I993J THE THREE FLAGS and blue ribbon on his men, in January 1811 This was OF GENERAL BELGRANO an open gesture of defiance against the president of the Junta, Colonel Cornelio de Saavedra For there was David Prando a rift between liberals, citizens of Buenos Aires the most of them, and conservatives, provincials in the majority. The revolution that took place in Buenos Aires, Moldes' colours soon became those of Buenos Aires, on May 25, 1810, saw a display of white and red rib but he never got any credit for them. bons'- the local colours since the British Invasions of Shortly after the conservative coup d'etat of April 5-6, 1806-07T Red and white stood for liberty and union the Liberal Patriotic Society and the America Regiment respectively, and were, of course, the first Argentine which supported it, were prosecuted and purged by colours under which monarchists and republ.cans ral Saavedra. And also the bicolour cockade was forbid lied, in their struggle against the Spaniards, even den. White ribbons and Spanish red cockades prevailed, though they simulated loyalty to the captive king together with the idea of an autonomous union within Ferdinand VII And Buenos Aires even had a secret flag, the Spanish Empire. But in August, Saavedra was which probably had the same colours' overthrown by the oppos't'on, and in the following In August of the same year, Jos$ de Moldes was month blue and white nbbons became all the rage in appointed Lieutenant Governor of the city of Mendoza Buenos Aires. -

The State Flag of Georgia: the 1956 Change in Its Historical Context

The State Senate Senate Research Office Bill Littlefield 204 Legislative Office Building Telephone Managing Director 18 Capitol Square 404/ 656 0015 Atlanta, Georgia 30334 Martha Wigton Fax Director 404/ 657 0929 The State Flag of Georgia: The 1956 Change In Its Historical Context Prepared by: Alexander J. Azarian and Eden Fesshazion Senate Research Office August 2000 Table of Contents Preface.....................................................................................i I. Introduction: National Flags of the Confederacy and the Evolution of the State Flag of Georgia.................................1 II. The Confederate Battle Flag.................................................6 III. The 1956 Legislative Session: Preserving segregation...........................................................9 IV. The 1956 Flag Change.........................................................18 V. John Sammons Bell.............................................................23 VI. Conclusion............................................................................27 Works Consulted..................................................................29 Preface This paper is a study of the redesigning of Georgia’s present state flag during the 1956 session of the General Assembly as well as a general review of the evolution of the pre-1956 state flag. No attempt will be made in this paper to argue that the state flag is controversial simply because it incorporates the Confederate battle flag or that it represents the Confederacy itself. Rather, this paper will focus on the flag as it has become associated, since the 1956 session, with preserving segregation, resisting the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, and maintaining white supremacy in Georgia. A careful examination of the history of Georgia’s state flag, the 1956 session of the General Assembly, the designer of the present state flag – John Sammons Bell, the legislation redesigning the 1956 flag, and the status of segregation at that time, will all be addressed in this study. -

Flags Over Antarctica

Flags over Antarctica Edward Kaye Abstract Graham Bartram’s unofficial 1995 flag for Antarctica first flew over the White Continent on the last day of 2002. Ted Kaye raised it onshore at several locations on Antarctica’s Danco Coast and the South Shetland Islands. He presented it to the commanders of the scientific bases of Bra- zil, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine and flew it on the expedition vessel M/V Orlova. One of several flags for Antarctica, the most recent design displays the continent in white on a field of United Nations blue. The designer explicitly intended to fulfill both reasons for “mappy flags” later identified by Mason Kaye (Maps on Flags, ICV XIX, 2001): uniqueness and neutrality. The actual flags were provided by Outpost Flags (Wisconsin, USA). Under the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, the 12 countries most involved in the continent’s his- tory and exploration agreed to defer their territorial claims. 44 nations have now signed the treaty, although many maintain a presence there and fly their own flags or specific territorial flags in order to protect their interests.1 Antarctica is thus the sovereign terri- tory of no country, without an official flag of its own. However, several proposals for unofficial flags have been developed. In 1985 Dr. Whitney Smith proposed a design for Antarctica: “on an orange background, off-center near the hoist, a design in white consisting of a pair of stylized hands framing a circle segment below a capital A.” (Fig. 1). The circle segment repre- sents the area of the globe below 60° south, the hands are for protection of the environ- ment, the negative [orange] space between the hands and segment is the dove of peace, and the “A” is for Antarctica and combines with the segment to suggest the scales of justice. -

Geography History — Year 3 Levels: L — 1St Through 4Th M — 5Th Through 8Th

Created July 2017 *Please note that this is a copy and therefore has not been updated since its creation date. If you find a link issue or typo here, please check the actual course before bringing it to our attention. Thank you.* History — Geography History — Year 3 Levels: L — 1st through 4th M — 5th through 8th Please review the FAQs and contact us if you find a problem with a link. Course Description: Students will travel the world learning the locations, histories and physical geography of countries, names of capitals, famous landmarks, unique expressions of culture, and facts about the world around them. Students will learn to read maps and create their own. Students will share what they are learning by creating a variety of projects including brochures, commercials, and tours. The course culminates with creating an immersive cultural experience to share with family and friends. Reading List: L folk tales, M Around the World in 80 Days Note: Throughout the course the students, both levels, will be playing Seterra. I have linked to the online version within the course. You may want to use the link here (if you use Windows) and download it to your computer. If you use it online, realize that it starts right away when you open the window. It will slow your computer down if you just leave it running. I suggest closing the window when you are done your game. Materials: • Basic Supplies • History, Year 3, Level L • History, Year 3, Level M Day 1 L 1. This year we’re going to be learning about the places of the world and the people in it. -

Koda Opis 000100 Buttoning Frame with Small Buttons € 32.14 000200

Cena (brez 22% Koda Opis DDV) 000100 Buttoning Frame With Small Buttons € 32.14 000200 Buttoning Frame With Large Buttons € 32.14 000300 Bow Tying Frame € 32.14 000400 Lacing Frame € 32.14 000500 Hook And Eye Frame € 32.14 000600 Safety Pin Frame € 32.14 000700 Snapping Frame € 32.14 000800 Zipping Frame € 32.14 000900 Buckling Frame € 40.00 001000 Shoe Buttoning Frame € 40.00 001100 Shoe Lacing Frame € 32.14 001200 Velcro Frame € 32.14 001240 Smooth Gradation Board € 14.22 0012A0 Rough And Smooth Boards Set € 33.00 001300 Pressure Cylinders € 119.38 001400 Rough Gradation Tablets € 42.50 001440 Smooth Gradation Tablets € 42.50 001450 Fabric Box € 56.65 001500 Smelling Bottles € 84.48 001550 Tasting Exercise € 60.59 001600 Sound Boxes € 120.00 001700 Baric Tablets € 61.48 001730 Mystery Bags: Empty € 18.91 001740 Mystery Bags: Geometric Shapes € 32.50 001770 Mystery Bag: Familiar Items € 32.50 001800 Thermic Bottles € 217.45 0018A0 Thermic Tablets € 62.44 001900 Cylinder Block No. 1 € 65.19 002000 Cylinder Block No. 2 € 65.19 002100 Cylinder Block No. 3 € 65.19 002200 Cylinder Block No. 4 € 65.19 002300 Set Of Knobless Cylinders € 169.00 002400 The Pink Tower € 98.26 002410 Stand For Pink Tower € 28.46 002420 Box With Cubes For Pink Tower € 31.22 002500 The Brown Stair € 135.90 002550 The Brown Stair: Brown Lacquer € 169.87 002520 Box With Prisms For Brown Stair € 42.00 002600 The Red Rods € 129.00 002700 Number Rods € 160.69 002720 Numerals And Signs: International Version € 136.20 0027A3 Numerals And Signs: US Version € 136.20 002813