Is There Evidence for Evidentiality in Gascony Occitan?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cartographie Des Territoires Couverts Par Le Dispositif MAIA En Ariège

Cartographie des territoires couverts par le dispositif MAIA en Ariège PAYS DU COUSERANS Cantons < 2014 Cantons > 2014 Communes Saint-Girons Portes du Couserans Bagert, Barjac, La Bastide-du-Salat, Saint-Lizier Bédeille, Betchat, Caumont, Cazavet, Oust Cérizols, Contrazy, Fabas, Gajan, Massat Lacave, Lasserre, Lorp-Sentaraille, Castillon Mauvezin-de-Prat, Mauvezin-de-Sainte- Sainte-Croix Volvestre Croix, Mercenac, Mérigon, Montardit, Labastide de Sérou Montesquieu-Avantès, Montgauch, Montjoie-en-Couserans, Prat-Bonrepaux, Saint-Lizier, Sainte-Croix-Volvestre, Taurignan-Castet, Taurignan-Vieux, Tourtouse Couserans Ouest Antras, Argein, Arrien-en-Bethmale, Arrout, Aucazein, Audressein, Augirein, Balacet, Balaguères, Bethmale, Bonac- Irazein, Les Bordes-sur-Lez, Buzan, Castillon-en-Couserans, Cescau, Engomer, Eycheil, Galey, Illartein, Montégut-en-Couserans, Moulis, Orgibet, Saint-Girons, Saint-Jean-du- Castillonnais, Saint-Lary, Salsein, Sentein, Sor, Uchentein, Villeneuve. Couserans Est Aigues-Juntes, Aleu, Allières, Alos, Alzen, Aulus-les-Bains, La Bastide-de- Sérou, Biert, Boussenac, Cadarcet, Castelnau-Durban, Clermont, Couflens, Durban-sur-Arize, Encourtiech, Ercé, Erp, Esplas-de-Sérou, Lacourt, Larbont, Lescure, Massat, Montagagne, Montels, Montseron, Nescus, Oust, Le Port, Rimont, Rivèrenert, Seix, Sentenac- d'Oust, Sentenac-de-Sérou, Soueix- Rogalle, Soulan, Suzan, Ustou. PAYS DES PORTES D’ARIEGE Cantons < 2014 Cantons > 2014 Communes Saverdun Arize-Lèze Artigat, La Bastide-de-Besplas, Les Bordes-sur-Arize, Pamiers Ouest Camarade, Campagne-sur-Arize, Carla-Bayle, Pamiers Est Castéras, Castex, Daumazan-sur-Arize, Durfort, Le Fossat Fornex, Le Fossat, Gabre, Lanoux, Lézat-sur-Lèze, Le Mas d’Azil Loubaut, Le Mas-d'Azil, Méras, Monesple, Montfa, Pailhès, Sabarat, Saint-Ybars, Sainte-Suzanne, Sieuras, Thouars-sur-Arize, Villeneuve-du-Latou Portes d’Ariège La Bastide-de-Lordat, Bonnac, Brie, Canté, Esplas, Gaudiès, Justiniac, Labatut, Lissac, Mazères, Montaut, Saint-Quirc, Saverdun, Trémoulet, Le Vernet, Villeneuve-du-Paréage. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

S3renr Occitanie - Concertation Préalable Du Public Du 8 Avril Au 20 Mai 2021 Cahier D’Acteur

S3REnR Occitanie - Concertation préalable du public du 8 avril au 20 mai 2021 Cahier d’acteur Nom de la contribution Contribution de la Communauté de Communes Couserans-Pyrénées sur les zones 1 (Pyrénées Ouest) et 3 (Ariège et Garonne) : capacités insuffisantes Résumé de la contribution (Décrivez la contribution en quelques lignes) La Communauté de Communes Couserans-Pyrénées (CCCP), engagée depuis 2020 dans un PCAET, et « collectivité pilote pour le développement de projets d’énergies renouvelables territoriaux », informe du besoin d’augmenter les capacités sur son territoire, insuffisantes par rapport aux projets prévus et aux objectifs du PCAET pour devenir Territoire à Energie Positive (TEPOS). Emetteur de la contribution Nom de l’organisme Communauté de Communes Couserans-Pyrénées (personne morale) Adresse 1 rue de de l’Hôtel Dieu, 09170 Saint-Lizier Tél 0638648496 Courriel de contact [email protected] Objectif(s) de la contribution L’objectif de la présente contribution est de pointer l’inadéquation entre les capacités prévues et les objectifs et les projets du territoire, afin que les aménagements à prévoir par le S3REnR sur le réseau prennent en compte les besoins en raccordement et en acheminement. Exposé argumenté La Communauté de Communes Couserans-Pyrénées (CCCP) est engagée depuis 2020 dans un PCAET, avec l’objectif de devenir territoire à énergie positive (TEPOS) à l’horizon 2050, ce qui implique de doubler sa production d’énergies renouvelables. La CCCP a été lauréate de l’appel à projet Ademe/Région « collectivité pilote pour le développement de projets d’énergies renouvelables territoriaux » avec pour objectif l’élaboration d’une programmation énergétique territoriale et le développement de projets d’énergies renouvelables. -

Ariège, France

Late Holocene history of woodland dynamics and wood use in an ancient mining area of the Pyrenees (Ariège, France) Vanessa Py, Raquel Cunill Artigas, Jean-Paul Métailié, Bruno Ancel, Sandrine Baron, Sandrine Paradis-Grenouillet, Emilie Lerigoleur, Nassima Badache, Hugues Barcet, Didier Galop To cite this version: Vanessa Py, Raquel Cunill Artigas, Jean-Paul Métailié, Bruno Ancel, Sandrine Baron, et al.. Late Holocene history of woodland dynamics and wood use in an ancient mining area of the Pyrenees (Ariège, France). Quaternary International, Elsevier, 2017, 458, pp.141 - 157. 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.01.012. hal-01760722 HAL Id: hal-01760722 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01760722 Submitted on 14 Sep 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Quaternary International 458 (2017) 141e157 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Late Holocene history of woodland dynamics and wood use in an ancient mining area of the Pyrenees (Ariege, France) * Vanessa Py-Saragaglia -

Diagnostic Air Energie Climat Du Territoire De La Communauté De Communes Couserans Pyrénées 2018 - PCAET

Diagnostic Air Energie Climat du territoire de la Communauté de Communes Couserans Pyrénées 2018 - PCAET COMMUNAUTE DE COMMUNES COUSERANS-PYRENEES 1 rue de l’Hôtel Dieu 09190 SAINT-LIZIER Téléphone : 05 64 37 19 41 2 1 Table des matières 2 – Introduction ................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Le territoire de la CCCP ............................................................................................ 6 2.1.1 Présentation du territoire .................................................................................. 6 2.1.2 Enjeux du territoire ........................................................................................... 6 2.1.3 Actions déjà engagées sur le territoire et compétences de l’EPCI .................... 7 2.2 Les enjeux liés au changement climatique ...............................................................18 2.2.1 La prise en charge politique de la question climatique .....................................19 2.2.2 Qu’est-ce qu’un Plan Climat Air Energie Territorial ? .......................................21 2.2.3 La démarche de la Communauté de Communes Couserans Pyrénées ..........22 2.2.4 Les projections des organismes professionnels ..............................................22 3 – Bilan des émissions de polluants atmosphériques .............................. 24 3.1 Contexte d’élaboration du diagnostic .......................................................................24 3.1.1 Le SRCAE .......................................................................................................24 -

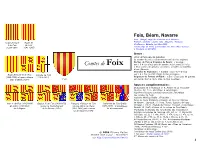

Comtes De Foix

Foix, Béarn, Navarre Foix : (Ariège) siège du Sénéchal de la Province ; Pamiers : Evêché ; autres cités : Mazères, Tarascon, Roger-Bernard Roger IV Vic-Dessos, Belesta, Le Mas-d’Azil. II de Foix de Foix Comté érigé en Pairie (par Charles VII, par Lettres données (1223-1241) (1241-1265) à Vendôme en 08/1458) Armes : «D’or, à trois pals de gueules» (le nombre de pals a constamment varié dès les origines) Comtes de Foix & Vicomtes de Béarn : « écartelé : Comtes de Foix aux 1 & 4 d’or à trois pals de gueules (Foix) ; aux 2 & 3 d’or, à deux vaches de gueules, accornées, accollées & clairinées d’azur (Béarn)». Vicomtes de Castelbon : « écartelé : aux 1 & 4 de Foix ; Roger-Bernard III de Foix Isabelle de Foix aux 2 & 3 d’or, au chef chargé de trois losanges». (1265-1302) et après alliance (1398-1412) Seigneurs de Fornets et Rabat : « D’or, à trois pals de gueules, avec le Béarn (1281) Foix sur l’angle droit de l’écu, brisé de trois losanges». Sources complémentaires : Dictionnaire de la Noblesse (F. A. Aubert de La Chesnaye- Desbois, éd. 1775, Héraldique & Généalogie), http://www.foixstory.com/data/contact.htm (héraldique des comtes de Foix), Aquitaine Nobility (Grailly et Foix) dont : Actes de Cluny, Pamplona, Obituaires de Sens & Chartreux de Vauvert ; Lagrasse, J.C.Chuat, Trunus, Szabolcs de Vajay ; Jean 1er de Foix (1412-1436) Gaston IV de Foix (1436-1472) François «Febus» de Foix Catherine de Foix-Grailly Michelet, J, (1971) «Histoire de France», Froissart, «Chroniques» ; et après l’acquisition & avec le Gouvernement comme prince de Viane (1483-1516) : 2 hypothèses Doublet, G. -

La Vallée De La Bellongue (Pyrénées-Couserans) Au Moyen Âge Stéphane Bourdoncle, Florence Guillot, Thibaut Lasnier, Hélène Teisseire, Bourdoncle Stéphane

La vallée de la Bellongue (Pyrénées-Couserans) au Moyen Âge Stéphane Bourdoncle, Florence Guillot, Thibaut Lasnier, Hélène Teisseire, Bourdoncle Stéphane To cite this version: Stéphane Bourdoncle, Florence Guillot, Thibaut Lasnier, Hélène Teisseire, Bourdoncle Stéphane. La vallée de la Bellongue (Pyrénées-Couserans) au Moyen Âge. Revue de Comminges et des Pyrénées centrales, Société des Études du Comminges, 2006, 2006 (2), pp.173-208. hal-02458385 HAL Id: hal-02458385 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02458385 Submitted on 28 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. La vallée de la Bellongue (Pyrénées-Couserans) au Moyen Age Stéphane BOURDONCLE1 Florence GUILLOT2 Thibaut LASNIER3 Hélène TEISSEIRE4 La vallée de la Bellongue est située dans les Pyrénées centrales françaises entre les départements de l’Ariège et de la Haute-Garonne. Elle a été pendant deux ans le cadre d’une prospection archéologique doublée d’une enquête documentaire réalisée par Hélène TEISSEIRE et Florence GUILLOT, d’une étude linguistique par Stéphane BOURDONCLE, en même temps qu’une recherche de Master 1 menée par Thibaut LASNIER qui en inventoriait les sites fortifiés 5 . Ces actions s’intègrent au Programme Collectif de Recherche mené depuis 2004 sur le sujet « Naissance, fonctions et évolutions des fortifications à l’époque médiévale dans les comtés de Foix, Couserans et Comminges »6. -

'Living Like a King? the Entourage of Odet De Foix, Vicomte De Lautrec

2015 II ‘Living Like a King? The Entourage of Odet de Foix, Vicomte de Lautrec, Governor of Milan’, Philippa Woodcock, University of Warwick, Department of History, Article: Living Like a King Living Like a King? The Entourage of Odet de Foix, Vicomte de Lautrec, Governor of Milan Philippa Woodcock Abstract: In the early sixteenth century, the de Foix family were both kin and intimate councillors to the Valois kings, Louis XII and François I. With a powerbase in Guyenne, the de Foix tried to use their connections at court to profit from the French conquest of Milan, between 1499 and 1522. This paper will explore the career of one prominent family member, Odet de Foix, vicomte de Lautrec (1483-1528). Lautrec was a Marshal of France, who served in Italy as a soldier and governor. He was key to the royal entourage, amongst François I’s intimates at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. His sister, Françoise, was also the king’s mistress. The paper will examine Lautrec’s entourage from two aspects. Firstly, it presents how Lautrec established his entourage from his experience in Navarre and Italy and as a mem- ber of the royal retinue. It establishes the importance of familial and regional ties, but also demonstrates the important role played by men of talent. Secondly, it explores Lautrec’s relationship to his entourage once he became governor of Milan. Were ties of blood, ca- reer or positions of Italian prestige the most important aspects for a governor when he chose his intimates? Were compromises made with Italian traditions and elites to sustain his rule? Did he learn from the experience and failures of previous governors? This article contributes to a gap in scholarship for the later period of French Milan from 1515 to 1522. -

Great Tourist Sites

Great Tourist Sites in Midi-Pyrenees Your Holiday Destination Midi-Pyrénées, it rhymes with hurray! Great Tourist Sites in Midi-Pyrenees Holidays don’t just happen; they’re planned with the heart! Midi-Pyrénées has a simple goal: making you happy! Some places are so exceptional that people talk about them on the other side of the world. Their names evoke images that stir travellers’ emotions: Conques, Rocamadour, From Toulouse ‘the pink city’ to the banks of the Canal du Midi; from the amazing sight of the Cirque de Gavarnie to the Lourdes, Marciac, the Millau Viaduct, the Cirque de Gavarnie, the Canal du Midi…. Millau Viaduct; from authentic villages of character like Saint-Cirq-Lapopie to exuberant festivals like Jazz in Marciac; you These great sites create our region’s identity and are part of its infl uence, which extends can explore the many facets of a region whose joie de vivre is contagious! well beyond its borders. Step into the culture of Midi-Pyrénées and discover its accent, fl avours, laughter and generosity! Half-measures, regrets and To discover them, you need to expand your outlook and let yourself be guided by your restraint are not allowed. Enjoy your stay to the full, with a real passion. You’ll go home a different person! tastes and desires. Follow the Route des Bastides through fortifi ed towns or the Way of St James, criss-crossing through towns of art and history. Or revel in the freedom and Long live freedom, long live passion, long live Midi-Pyrénées! fresh air of the Pyrenean peaks. -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

PROJET DE TERRITOIRE DU COUSERANS 2016-2026 Pôle D

PROJET DE TERRITOIRE DU COUSERANS 2016-2026 Pôle d’Equilibre Territorial et Rural du Couserans Château de Rozès - 09190 SAINT LIZIER Juillet 2016 Approuvé par les communautés de communes de … SOMMAIRE Préambule : Pour continuer à préparer unis l’avenir du Couserans P3 Présentation du Couserans : éléments de cadrage P4 Méthodologie d’élaboration du projet : une concertation élargie P8 Feuilles de route proposées par les 6 commissions Pour un territoire économiquement ouvert, identifié, organisé et tourné vers la qualité P11 Le tourisme au cœur du Couserans : vers un accueil de qualité et une offre reconnue P27 Habiter et vivre mieux, à tous âges, en Couserans P39 Vivre, créer, partager : un projet culturel pour le Couserans P51 Pour un territoire sportif, vecteur d’une image dynamique et positive P63 Un environnement riche, de qualité, à préserver et partager P69 En synthèse : un projet au service de l’activité et de l’emploi durable P73 ANNEXES - Compositions de la Conférence des Maires et du Conseil de Développement P74 - Liens vers les cartes heuristiques, schémas de synthèse et calendriers prévisionnels 2016-2026 des actions clefs par commission thématique P77 - Liste des fiches actions de la politique de la ville P84 Rappels : - Bilan qualitatif de 10 ans de politique de développement pour le Pays P87 - Bilan du Plan Opérationnel de Revitalisation de Saint-Girons et du Couserans P109 - 6 pages INSEE n°156 de février 2014 « Pays Couserans, un renouveau récent à confirmer » P121 Pour continuer à préparer unis l’avenir du Couserans Dans les années 2000, une démarche de développement territorial à l'échelle du Couserans a été impulsée, réunissant l'ensemble des intercommunalités que compte ce territoire via l’Association de Développement du Couserans (ADC) transformée ultérieurement en Syndicat mixte du Pays Couserans. -

Correspondence, Conferences, Documents, Volume XIV. Index

DePaul University Via Sapientiae Saint Vincent de Paul / Correspondence, Correspondence, Conferences, and Documents Conferences, Documents (English Translation) of St. Vincent de Paul 2014 Correspondence, Conferences, Documents, Volume XIV. Index. Vincent de Paul Pierre Coste C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/coste_en Recommended Citation Paul, Vincent de and Coste, Pierre C.M., "Correspondence, Conferences, Documents, Volume XIV. Index." (2014). Saint Vincent de Paul / Correspondence, Conferences, Documents (English Translation). 1. https://via.library.depaul.edu/coste_en/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Correspondence, Conferences, and Documents of St. Vincent de Paul at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Vincent de Paul / Correspondence, Conferences, Documents (English Translation) by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL INDEX ____________ VOLUME XIV SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL CORRESPONDENCE CONFERENCES, DOCUMENTS INDEX VOLUME XIV NEWLY TRANSLATED, EDITED, AND ANNOTATED FROM THE 1925 EDITION OF PIERRE COSTE, C.M. Edited by: SR. MARIE POOLE, D.C. Editor-in-Chief SR. ANN MARY DOUGHERTY, D.C., Editorial Assistant Translated by: SR. MARIE POOLE, D.C. Annotated by: REV. JOHN W. CARVEN, C.M. NIHIL OBSTAT Very Rev. Michael J. Carroll, C.M. President of the National Conference of Vincentian Visitors Published in the United States by New City Press 202 Comforter Blvd., Hyde Park, New York 12538 © 2014, National Conference of Visitors of the United States Cover by: Leandro DeLeon Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in -Publication Data: Vincent de Paul, Saint, 1581-1660 Correspondence, conferences, documents.