Is Chemically Dispersed Oil More Toxic to Atlantic Cod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials Supplementary Table S1: MGNC compound library Ingredien Molecule Caco- Mol ID MW AlogP OB (%) BBB DL FASA- HL t Name Name 2 shengdi MOL012254 campesterol 400.8 7.63 37.58 1.34 0.98 0.7 0.21 20.2 shengdi MOL000519 coniferin 314.4 3.16 31.11 0.42 -0.2 0.3 0.27 74.6 beta- shengdi MOL000359 414.8 8.08 36.91 1.32 0.99 0.8 0.23 20.2 sitosterol pachymic shengdi MOL000289 528.9 6.54 33.63 0.1 -0.6 0.8 0 9.27 acid Poricoic acid shengdi MOL000291 484.7 5.64 30.52 -0.08 -0.9 0.8 0 8.67 B Chrysanthem shengdi MOL004492 585 8.24 38.72 0.51 -1 0.6 0.3 17.5 axanthin 20- shengdi MOL011455 Hexadecano 418.6 1.91 32.7 -0.24 -0.4 0.7 0.29 104 ylingenol huanglian MOL001454 berberine 336.4 3.45 36.86 1.24 0.57 0.8 0.19 6.57 huanglian MOL013352 Obacunone 454.6 2.68 43.29 0.01 -0.4 0.8 0.31 -13 huanglian MOL002894 berberrubine 322.4 3.2 35.74 1.07 0.17 0.7 0.24 6.46 huanglian MOL002897 epiberberine 336.4 3.45 43.09 1.17 0.4 0.8 0.19 6.1 huanglian MOL002903 (R)-Canadine 339.4 3.4 55.37 1.04 0.57 0.8 0.2 6.41 huanglian MOL002904 Berlambine 351.4 2.49 36.68 0.97 0.17 0.8 0.28 7.33 Corchorosid huanglian MOL002907 404.6 1.34 105 -0.91 -1.3 0.8 0.29 6.68 e A_qt Magnogrand huanglian MOL000622 266.4 1.18 63.71 0.02 -0.2 0.2 0.3 3.17 iolide huanglian MOL000762 Palmidin A 510.5 4.52 35.36 -0.38 -1.5 0.7 0.39 33.2 huanglian MOL000785 palmatine 352.4 3.65 64.6 1.33 0.37 0.7 0.13 2.25 huanglian MOL000098 quercetin 302.3 1.5 46.43 0.05 -0.8 0.3 0.38 14.4 huanglian MOL001458 coptisine 320.3 3.25 30.67 1.21 0.32 0.9 0.26 9.33 huanglian MOL002668 Worenine -

Supp Table 6.Pdf

Supplementary Table 6. Processes associated to the 2037 SCL candidate target genes ID Symbol Entrez Gene Name Process NM_178114 AMIGO2 adhesion molecule with Ig-like domain 2 adhesion NM_033474 ARVCF armadillo repeat gene deletes in velocardiofacial syndrome adhesion NM_027060 BTBD9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 adhesion NM_001039149 CD226 CD226 molecule adhesion NM_010581 CD47 CD47 molecule adhesion NM_023370 CDH23 cadherin-like 23 adhesion NM_207298 CERCAM cerebral endothelial cell adhesion molecule adhesion NM_021719 CLDN15 claudin 15 adhesion NM_009902 CLDN3 claudin 3 adhesion NM_008779 CNTN3 contactin 3 (plasmacytoma associated) adhesion NM_015734 COL5A1 collagen, type V, alpha 1 adhesion NM_007803 CTTN cortactin adhesion NM_009142 CX3CL1 chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 adhesion NM_031174 DSCAM Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule adhesion NM_145158 EMILIN2 elastin microfibril interfacer 2 adhesion NM_001081286 FAT1 FAT tumor suppressor homolog 1 (Drosophila) adhesion NM_001080814 FAT3 FAT tumor suppressor homolog 3 (Drosophila) adhesion NM_153795 FERMT3 fermitin family homolog 3 (Drosophila) adhesion NM_010494 ICAM2 intercellular adhesion molecule 2 adhesion NM_023892 ICAM4 (includes EG:3386) intercellular adhesion molecule 4 (Landsteiner-Wiener blood group)adhesion NM_001001979 MEGF10 multiple EGF-like-domains 10 adhesion NM_172522 MEGF11 multiple EGF-like-domains 11 adhesion NM_010739 MUC13 mucin 13, cell surface associated adhesion NM_013610 NINJ1 ninjurin 1 adhesion NM_016718 NINJ2 ninjurin 2 adhesion NM_172932 NLGN3 neuroligin -

Whole Genome Sequencing of Finnish Type 1 Diabetic Siblings Discordant for Kidney Disease Reveals DNA Variants Associated with Diabetic Nephropathy

Supplementary Data Whole genome sequencing of Finnish type 1 diabetic siblings discordant for kidney disease reveals DNA variants associated with diabetic nephropathy Jing Guo, Owen J.L. Rackham, Bing He, Anne-May Österholm, Niina Sandholm, Erkka Valo, Valma Harjutsalo, Carol Forsblom, Iiro Toppila, Maikki Parkkonen, Qibin Li, Wenjuan Zhu, Nathan Harmston, Sonia Chothani, Miina K. Öhman, Eudora Eng, Yang Sun, Enrico Petretto, Per-Henrik Groop, Karl Tryggvason Supplementary Material: Whole Genome Sequencing on Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy Sibling cohort Table of contents Supplementary Methods ............................................................ 3 Supplementary Results .............................................................. 9 Supplementary Tables ............................................................. 11 Supplementary Table 1. Comparison of DNA sequencing quality using the Illumina and Complete Genomics platforms. ......................................................................11 Supplementary Table 2. Annotation of SNVs and indels identified in 161 genomes in the Discovery cohort by RefSeq. ......................................................................12 Supplementary Table 3. Frameshift-causing small insertions and deletions (indels) found in DN cases-only or controls-only individuals of the Finnish T1D DSP discovery cohort ...................................................................................................13 Supplementary Table 4. Recurrently mutated regions (RMR) significantly overrepresented -

Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of Mirnas Complementary to Upstream Sequences of Mrna Transcription Start Sites

In: Gene Silencing: Theory, Techniques and Applications ISBN: 978-1-61728-276-8 Editor: Anthony J. Catalano © 2010 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. The exclusive license for this PDF is limited to personal printing only. No part of this digital document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted commercially in any form or by any means. The publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this digital document, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of information contained herein. This digital document is sold with the clear understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, medical or any other professional services. Chapter XIII Genome-wide Identification and Analysis of miRNAs Complementary to Upstream Sequences of mRNA Transcription Start Sites Kenta Narikawa1, Kenji Nishi2, Yuki Naito2, Minami Mazda2 and Kumiko Ui-Tei1,2,* 1Department of Computational Biology, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, University of Tokyo, 5-1-5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa-shi, Chiba-ken 277-8561, Japan 2Department of Biophysics and Biochemistry, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, 2-11-16 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0032, Japan Abstract Small regulatory RNAs including short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) are crucial regulators of gene expression at the posttranscriptional level. Recently, additional roles for small RNAs in gene activation and suppression at the transcriptional level were reported; these RNAs were shown to have sequences that closely or completely match to their respective promoter regions. -

Germline PTPRT Mutation Potentially Involved in Cancer Predisposition

Germline PTPRT mutation potentially involved in cancer predisposition Lorena Martin1, Victor Lorca2, Pedro P´erez-Segura2, Patricia Llovet1, Vanesa Garc´ıa-Barber´an3, Maria Luisa Gonzalez-Morales2, Sami Belhad4, Gabriel Capell´a5, Laura Valle4, Miguel de la Hoya2, Pilar Garre6, and Trinidad Caldes2 1Hospital Clinico San Carlos. IdISCC 2Hospital Clinico San Carlos. IdISSC 3Hospital Cl´ınicoSan Carlos, IdISCC, CIBERONC 4IDIBELL 5ICO-IDIBELL 6Hospital clinico San Carlos. IdISSC September 17, 2020 Abstract Familial Colorectal Cancer Type X (FCCTX) is a term used to describe a group of families with an increased predisposition to colorectal and other related cancers, but an unknown genetic basis. Whole-exome sequencing in two cancer-affected and one healthy members of a FCCTX family revealed a truncating germline mutation in PTPRT [c.4090dup, p.(Asp1364GlyfsTer24)]. PTPRT encodes a receptor phosphatase and is a tumor suppressor gene found to be frequently mutated at somatic level in many cancers, having been proven that these mutations act as drivers that promote tumor development. This germline variant shows a compatible cosegregation with cancer in the family and results in the loss of a significant fraction of the second phosphatase domain of the protein, which is essential for PTPRT's activity. In addition, the tumors of the carriers exhibit epigenetic inactivation of the wild-type allele and an altered expression of PTPRT downstream target genes, consistent with a causal role of this germline mutation in the cancer predisposition of the family. Although PTPRT's role cancer initiation and progression has been well studied, this is the first time that a germline PTPRT mutation is linked with cancer susceptibility and hereditary cancer, which highlights the relevance of the present study. -

MAP3K11 Is a Tumor Suppressor Targeted by the Oncomir Mir-125B in Early B Cells

Cell Death and Differentiation (2016) 23, 242–252 & 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1350-9047/16 www.nature.com/cdd MAP3K11 is a tumor suppressor targeted by the oncomiR miR-125b in early B cells U Knackmuss1,4,5, SE Lindner2,5, T Aneichyk3, B Kotkamp1, Z Knust1, A Villunger2 and S Herzog1,2 MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small, non-coding RNAs that posttranscriptionally regulate gene expression and thereby control most, if not all, biological processes. Aberrant miRNA expression has been linked to a variety of human diseases including cancer, but the underlying molecular mechanism often remains unclear. Here we have screened a miRNA expression library in a growth factor-dependent mouse pre-B-cell system to identify miRNAs with oncogenic activity. We show that miR-125b is sufficient to render pre-B cells growth factor independent and demonstrate that continuous expression of miR-125b is necessary to keep these cells in a transformed state. Mechanistically, we find that the expression of miR-125b protects against apoptosis induced by growth factor withdrawal, and that it blocks the differentiation of pre-B to immature B cells. In consequence, miR-125b-transformed cells maintain expression of their pre-B-cell receptor that provides signals for continuous proliferation and survival even in the absence of growth factor. Employing microarray analysis, we identified numerous targets of miR-125b, but only reconstitution of MAP3K11, a critical regulator of mitogen- and stress-activated kinase signaling, interferes with the cellular fitness of the transformed cells. Together, this indicates that MAP3K11 might function as an important tumor suppressor neutralized by oncomiR-125b in B-cell leukemia. -

Components of Genetic Associations Across 2,138 Phenotypes

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/442715; this version posted October 14, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Components of genetic associations across 2,138 2 phenotypes in the UK Biobank highlight novel adipocyte 3 biology 4 5 Yosuke Tanigawa1*, Jiehan Li2,3*, Johanne Marie Justesen1,2,4, Heiko Horn5,6, 6 Matthew Aguirre1,7, Christopher DeBoever1,8, Chris Chang9, Balasubramanian Narasimhan1,10, 7 Kasper Lage5,6,11, Trevor Hastie1,10, Chong Yon Park2, Gill Bejerano1,7,12,13, Erik Ingelsson2,3*+, 8 Manuel A. Rivas1*+ 9 1. Department of Biomedical Data Science, School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. 10 2. Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. 11 3. Stanford Cardiovascular Institute, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. 12 4. Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, 13 University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 14 5. Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. 15 6. Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA. 16 7. Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. 17 8. Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. 18 9. Grail, Inc., 1525 O’Brien Drive, Menlo Park, CA, USA. 19 10. Department of Statistics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. 20 11. Institute for Biological Psychiatry, Mental Health Center Sct. -

Mrna Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats As Measured by Microarray Analysis

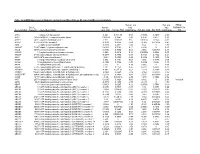

Table 3S: mRNA Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats as Measured by Microarray Analysis Human_avg Rat_avg_ PENG_ Entrez. Human_ log2_ log2_ RAPAMYCIN Gene.Symbol Gene.ID Gene Description avg_tstat Human_FDR foldChange Rat_avg_tstat Rat_FDR foldChange _DN A1BG 1 alpha-1-B glycoprotein 4.982 9.52E-05 0.68 -0.8346 0.4639 -0.38 A1CF 29974 APOBEC1 complementation factor -0.08024 0.9541 -0.02 0.9141 0.421 0.10 A2BP1 54715 ataxin 2-binding protein 1 2.811 0.01093 0.65 0.07114 0.954 -0.01 A2LD1 87769 AIG2-like domain 1 -0.3033 0.8056 -0.09 -3.365 0.005704 -0.42 A2M 2 alpha-2-macroglobulin -0.8113 0.4691 -0.03 6.02 0 1.75 A4GALT 53947 alpha 1,4-galactosyltransferase 0.4383 0.7128 0.11 6.304 0 2.30 AACS 65985 acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase 0.3595 0.7664 0.03 3.534 0.00388 0.38 AADAC 13 arylacetamide deacetylase (esterase) 0.569 0.6216 0.16 0.005588 0.9968 0.00 AADAT 51166 aminoadipate aminotransferase -0.9577 0.3876 -0.11 0.8123 0.4752 0.24 AAK1 22848 AP2 associated kinase 1 -1.261 0.2505 -0.25 0.8232 0.4689 0.12 AAMP 14 angio-associated, migratory cell protein 0.873 0.4351 0.07 1.656 0.1476 0.06 AANAT 15 arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase -0.3998 0.7394 -0.08 0.8486 0.456 0.18 AARS 16 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 5.517 0 0.34 8.616 0 0.69 AARS2 57505 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (putative) 1.701 0.1158 0.35 0.5011 0.6622 0.07 AARSD1 80755 alanyl-tRNA synthetase domain containing 1 4.403 9.52E-05 0.52 1.279 0.2609 0.13 AASDH 132949 aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase -0.8921 0.4247 -0.12 -2.564 0.02993 -0.32 AASDHPPT 60496 aminoadipate-semialdehyde -

Table S1. 103 Ferroptosis-Related Genes Retrieved from the Genecards

Table S1. 103 ferroptosis-related genes retrieved from the GeneCards. Gene Symbol Description Category GPX4 Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Protein Coding AIFM2 Apoptosis Inducing Factor Mitochondria Associated 2 Protein Coding TP53 Tumor Protein P53 Protein Coding ACSL4 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4 Protein Coding SLC7A11 Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 Protein Coding VDAC2 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 2 Protein Coding VDAC3 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 3 Protein Coding ATG5 Autophagy Related 5 Protein Coding ATG7 Autophagy Related 7 Protein Coding NCOA4 Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 4 Protein Coding HMOX1 Heme Oxygenase 1 Protein Coding SLC3A2 Solute Carrier Family 3 Member 2 Protein Coding ALOX15 Arachidonate 15-Lipoxygenase Protein Coding BECN1 Beclin 1 Protein Coding PRKAA1 Protein Kinase AMP-Activated Catalytic Subunit Alpha 1 Protein Coding SAT1 Spermidine/Spermine N1-Acetyltransferase 1 Protein Coding NF2 Neurofibromin 2 Protein Coding YAP1 Yes1 Associated Transcriptional Regulator Protein Coding FTH1 Ferritin Heavy Chain 1 Protein Coding TF Transferrin Protein Coding TFRC Transferrin Receptor Protein Coding FTL Ferritin Light Chain Protein Coding CYBB Cytochrome B-245 Beta Chain Protein Coding GSS Glutathione Synthetase Protein Coding CP Ceruloplasmin Protein Coding PRNP Prion Protein Protein Coding SLC11A2 Solute Carrier Family 11 Member 2 Protein Coding SLC40A1 Solute Carrier Family 40 Member 1 Protein Coding STEAP3 STEAP3 Metalloreductase Protein Coding ACSL1 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 1 Protein -

Signatures of Adaptive Evolution in Platyrrhine Primate Genomes 5 6 Hazel Byrne*, Timothy H

1 2 Supplementary Materials for 3 4 Signatures of adaptive evolution in platyrrhine primate genomes 5 6 Hazel Byrne*, Timothy H. Webster, Sarah F. Brosnan, Patrícia Izar, Jessica W. Lynch 7 *Corresponding author. Email [email protected] 8 9 10 This PDF file includes: 11 Section 1: Extended methods & results: Robust capuchin reference genome 12 Section 2: Extended methods & results: Signatures of selection in platyrrhine genomes 13 Section 3: Extended results: Robust capuchins (Sapajus; H1) positive selection results 14 Section 4: Extended results: Gracile capuchins (Cebus; H2) positive selection results 15 Section 5: Extended results: Ancestral Cebinae (H3) positive selection results 16 Section 6: Extended results: Across-capuchins (H3a) positive selection results 17 Section 7: Extended results: Ancestral Cebidae (H4) positive selection results 18 Section 8: Extended results: Squirrel monkeys (Saimiri; H5) positive selection results 19 Figs. S1 to S3 20 Tables S1–S3, S5–S7, S10, and S23 21 References (94 to 172) 22 23 Other Supplementary Materials for this manuscript include the following: 24 Tables S4, S8, S9, S11–S22, and S24–S44 1 25 1) Extended methods & results: Robust capuchin reference genome 26 1.1 Genome assembly: versions and accessions 27 The version of the genome assembly used in this study, Sape_Mango_1.0, was uploaded to a 28 Zenodo repository (see data availability). An assembly (Sape_Mango_1.1) with minor 29 modifications including the removal of two short scaffolds and the addition of the mitochondrial 30 genome assembly was uploaded to NCBI under the accession JAGHVQ. The BioProject and 31 BioSample NCBI accessions for this project and sample (Mango) are PRJNA717806 and 32 SAMN18511585. -

GC Skew at the 59 and 39 Ends of Human Genes Links R-Loop Formation to Epigenetic Regulation and Transcription Termination

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 27, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research GC skew at the 59 and 39 ends of human genes links R-loop formation to epigenetic regulation and transcription termination Paul A. Ginno,1,3,4 Yoong Wearn Lim,1,3 Paul L. Lott,2 Ian Korf,1,2 and Fre´de´ric Che´din1,2,5 1Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, 2Genome Center, University of California, Davis, California 95616, USA Strand asymmetry in the distribution of guanines and cytosines, measured by GC skew, predisposes DNA sequences toward R-loop formation upon transcription. Previous work revealed that GC skew and R-loop formation associate with a core set of unmethylated CpG island (CGI) promoters in the human genome. Here, we show that GC skew can dis- tinguish four classes of promoters, including three types of CGI promoters, each associated with unique epigenetic and gene ontology signatures. In particular, we identify a strong and a weak class of CGI promoters and show that these loci are enriched in distinct chromosomal territories reflecting the intrinsic strength of their protection against DNA methylation. Interestingly, we show that strong CGI promoters are depleted from the X chromosome while weak CGIs are enriched, a property consistent with the acquisition of DNA methylation during dosage compensation. Furthermore, we identify a third class of CGI promoters based on its unique GC skew profile and show that this gene set is enriched for Polycomb group targets. Lastly, we show that nearly 2000 genes harbor GC skew at their 39 ends and that these genes are preferentially located in gene-dense regions and tend to be closely arranged.