The Selection and Training of Offshore Installation Managers for Crisis Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WARFARE OFFICERS CAREER HANDBOOK II Warfare Officers Career Handbook

WARFARE OFFICERS CAREER HANDBOOK II WARFARE OFFICERS CAREER HANDBooK Warfare O fficers C areer H andbook IV WARFARE OFFICERS CAREER HANDBooK Foreword The Warfare Officers Career Handbook provides information for members of the Royal Australian Navy’s Warfare community. For the purposes of this handbook, the Warfare community is deemed to include all officers of the Seaman, Pilot and Observer Primary Qualifications. The Warfare Officer Community symbiotically contains personnel from the seaman, Submarine, Aviation, Hydrographic and Meteorological, Mine Clearance Diving and Naval Communications and Intelligence groups. The Warfare Officers Career Handbook is a source document for Warfare Officers to consult as they progress through their careers. It is intended to inform and stimulate consideration of career issues and to provide a coherent guide that articulates Navy’s requirements and expectations. The book provides a summary of the Warfare branch specialisations and the sub-specialisations that are embedded within them, leading in due course to entry into the Charge Program and the Command opportunities that follow. The Warfare Officers Career Handbook also describes the historical derivation of current warfare streams to provide contemporary relevance and the cultural background within which maritime warfare duties are conducted. It discusses the national context in which Warfare Officers discharge their duties. Leadership and ethical matters are explored, as is the inter-relationship between personal attributes, values, leadership, performance and sense of purpose. There is no intention that this handbook replicate or replace extant policy and procedural guidelines. Rather, the handbook focuses on the enduring features of maritime warfare. Policy by its nature is transient. Therefore, as far as possible, the Warfare Officers Career Handbook deals with broad principles and not more narrowly defined policies that rightly belong in other documents. -

1892-1929 General

HEADING RELATED YEAR EVENT VOL PAGE ABOUKIR BAY Details of HM connections 1928/112 112 ABOUKIR BAY Action of 12th March Vol 1/112 112 ABUKLEA AND ABUKRU RM with Guards Camel Regiment Vol 1/73 73 ACCIDENTS Marine killed by falling on bayonet, Chatham, 1860 1911/141 141 RMB1 marker killed by Volunteer on Plumstead ACCIDENTS Common, 1861 191286, 107 85, 107 ACCIDENTS Flying, Captain RISK, RMLI 1913/91 91 ACCIDENTS Stokes Mortar Bomb Explosion, Deal, 1918 1918/98 98 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of Major Oldfield Vol 1/111 111 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Turkish Medal awarded to C/Sgt W Healey 1901/122 122 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Ball at Plymouth in 1804 to commemorate 1905/126 126 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of a Veteran 1907/83 83 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1928/119 119 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1929/177 177 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) 1930/336 336 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Syllabus for Examination, RMLI, 1893 Vol 1/193 193 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) of Auxiliary forces to be Captains with more than 3 years Vol 3/73 73 ACTON, MIDDLESEX Ex RM as Mayor, 1923 1923/178 178 ADEN HMS Effingham in 1927 1928/32 32 See also COMMANDANT GENERAL AND GENERAL ADJUTANT GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING of the Channel Fleet, 1800 1905/87 87 ADJUTANT GENERAL Change of title from DAGRM to ACRM, 1914 1914/33 33 ADJUTANT GENERAL Appointment of Brigadier General Mercer, 1916 1916/77 77 ADJUTANTS "An Unbroken Line" - eight RMA Adjutants, 1914 1914/60, 61 60, 61 ADMIRAL'S REGIMENT First Colonels - Correspondence from Lt. -

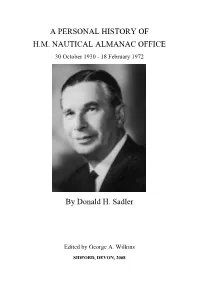

A Personal History of H.M

A PERSONAL HISTORY OF H.M. NAUTICAL ALMANAC OFFICE 30 October 1930 - 18 February 1972 By Donald H. Sadler Edited by George A. Wilkins SIDFORD, DEVON, 2008 2 DONALD H. SADLER © Copyright United Kingdom Hydrographic Office, 2008 A Personal History of H. M. Nautical Almanac Office by Dr. Donald H. Sadler, Superintendent of HMNAO 1936-1970, is a personal memoir; it does not represent the views of, and is not endorsed by, HMNAO or the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office. The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office grants permission to reproduce the document, in whole or in part, provided that it is reproduced unchanged and with the copyright notice intact. The photograph of Sadler taken when President, is reproduced by kind permission of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). If you wish to reproduce this picture, please contact the Librarian, Royal Astronomical Society, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BQ, United Kingdom. This work may be downloaded from HMNAO’s website at http://www.hmnao.com/history PERSONAL HISTORY OF H.M. NAUTICAL ALMANAC OFFICE, 1930-1972 3 SUMMARY OF CONTENTS Preface 10 Forewords by Donald H. Sadler 13 Prologue 15 Part 1: At Greenwich: 1930–1936 17 1. First impressions 17 2. Mainly about the work of the Office 22 3. Mainly about L. J. Comrie and his work 30 Part 2: At Greenwich: 1936–1939 39 4. Change and expansion 39 5. New developments 46 6. Procedures and moves 53 Part 3: At Bath: 1939–1949 57 7. Early days at Bath (before the move to Ensleigh) 57 8. From the move to Ensleigh to the end of the war 67 9. -

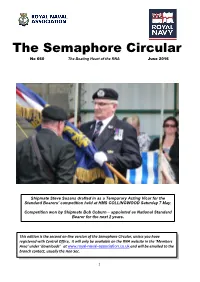

The Semaphore Circular No 660 the Beating Heart of the RNA June 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 660 The Beating Heart of the RNA June 2016 Shipmate Steve Susans drafted in as a Temporary Acting Vicar for the Standard Bearers’ competition held at HMS COLLINGWOOD Saturday 7 May. Competition won by Shipmate Bob Coburn – appointed as National Standard Bearer for the next 2 years. This edition is the second on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. Remembrance Paraded 13 November 2016 2. National Standard Bearers Competition 3. Mini Cruise 4. Guess Where? 5. Donations 6. Teacher Joke 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. RN VC Series – Capt Stephen Beattie 9. Finance Corner 10. St Lukes Hospital Haslar 11. Trust your Husband Joke 12. Assistance please – Ludlow Ensign 13. Further Assistance please Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations IMC International Maritime Confederation NSM Naval Service Memorial Throughout indicates -

2003 Lndelr Sht S Volume 38 Mcinthly F 5.00

2003 lndelr sht S Volume 38 McINTHLY f 5.00 I 30 years of lraditional seruice 5/30:35 ARose Blue 12l7r 30 years of Brittany Ferries 1/21 Alsatia 12140,12141* Atran 1/ll Altaskai pakol craft 1/19 Artevelde 4/45 Altmark 5/20 kun 3l5Z A Alwyn Vincent 8/39* Arundle crotle 10121, 12163 A bad day at the office, feature 1 'l /¿8-3 1 Alyssl'tll lfll0 Asama Maru 7|4o.,1111.0 A bouquet of Mersey daffodils (Mersey Special) 9/42 Ambra Fin 12154 Asanius 8/24 A new golden age forthe Maid 6/16-18 America Star 411*, 415, 7 12 Asgard ll 1 l/l 3 A port for the 21st cenluty 9/32-33 Amerian Adventure I 1/22 Asia'12/39' ¿ A. Lopez, screw steamship 5/26 Amerian Bankef Érgo ship 1 l/.l0 Asian Hercules 6/4 Shipping odyssey (Blue Funnel) 8/17 Amerian Range4 ergo ship 1 1/10 Asseburg l/12* Ticket to ride (Mersey Ferries) 6/1 6-20 Americ¡n Star 4/34 Assi Euro Link 4/4 Aütal role 7/20-21 iAmerigo Vespucci 6/54+, 8/30 Assyria 12139 Aasford'l/fc' Amerikanis 9146*,9148 Astoria 1212* AbelTroman 3/18 Amsterdam 2111*, 5130, 5134*, 5135 Astrea 9/52 Abercorn 4/33 Anchises 8/23r,8/24 Astraea 1ll42 Abercraig 8/,14,8.45* Anchor Line's argo vessel op€rations 5116 Asul6 7/40* Aadia 12127 Anchored in the past 5/l'l-17 Asturi$ 1/39 Accra 9/36 Ancon 5/38 Atalante 1f/22 Ae(¡nlury 1212* Ancona 5/7+ Athenia 1/,10, 3146, 5116, 6/50 'Achille lauro 9/47 Andania 12l¡O* Athlone Gstle 12163 Achilles 8/18 AndhikaAdhidaya 9/54* Atlantic 4/30, 1¿128 Adela¡de 11/47 Andrea 8/9 Atlantic convoys rememb€red 60 years on 7/1 3 Admhal Ghbanenko 7/13 Andrew Barker (lpswich) (Excursion Sh¡p SPecial) 6/42 Atlantic lifelines, feature 6/50-53 Admiral Gnier, ro+o 2/29 Andrewl. -

Mine Warfare and Diving

www.mcdoa.org.uk MINE WARFARE AND DIVING VOLUME 5 NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 1995 Official Use Only "%Za-S=C--- tifjel,41,1i4gisy: ..A!R • -SCIM11111516110:4%!. OPP peas F.MPORWM FIFTH ANNIVERSARY EDITION www.mcdoa.org.uk MINEWARFARE AND DIVING THE MAGAZINE OF THE MINEWARFARE AND DIVING COMMUNITY Front Cover: Montage of the last five years of MAD Magazine VOLUME 4 NUMBER 2 AUGUST 1994 CONTENTS EDITORIAL STAFF Foreword by Sponsor: Cdre. R.C. Moore Captain A S Ritchie OBE, ADC Royal Navy, 1 Publisher: Cdr. P.J. Gale Managing Editor: Lt. Cdr. N. R. Butterworth Diving Inspectorate 2 Deputy Editor: Lt. M.L. Kessler Minewarfare Reporter 4 Assistant Editor: CPO(MW) P. Whitehead Editorial Offices: MDT Department of SMOPS Warfare Branch Development - Update 5 HMS NELSON (GUNWHARF) Portsmouth. Hampshire, P01 3HH Australia's MCM Considerations 6 Telephone: 0705-822351 Ext: 24815 Naval Diving Training 8 Moving on and moving out 10 Minewarfare Trainers Update 12 COMMW 14 Plymouth Clearance Diving Unit - 1994 15 The Scotland, Northern England and Northern MINEWARFARE AND DIVING is published Ireland Clearance Diving Unit 18 twice-annually by the MDT Department of The type A two compartment compression SNIOPS on behalf of the Director of Naval chamber 19 Operations, Ministry of Defence. Rationalisation of Teams - Northern Diving Group 21 Third (Deep) MCM Squadron Update 22 Service units requesting copies of the Magazine Health and Safety Implementation in COMMW 23 should forward their applications to the Director of Naval Operations. CIO The Editorial Offices. Royal Saudi Naval Forces Minewarfare Diver Training Team 23 address as above. -

The British Flag-Ships

FRIDAY, MARCH 12th, 1897. THE BRITISH FLAG-SHIPS. Plioto. R. ELLIS, Malta, Copyright.—HUDSON & KEAKh- H.M.S. " RAMILLIES." Photo. SYMONDS & CO., Portsmouth. H.M.S. " RE VENGE" HE "Ramillies" and the "Revenge" are the two flag-ships of the British Mediterranean Fleet, the *' Ramillies" T flying the flag of Admiral Sir JOHN O. HOPKINS, K.C.B., the Commander-in-Chief, and the " Revenge," the flag-ship of Rear-Admiral ROBERT H. HARRIS, the second in command. The two ships are sister first-class battle-ships of the "Royal Sovereign" type, of 14,150 tons each, and identical in speed and manoeuvring capabilities—most important points for two ships which might lead separate groups of ships in action. In action, each flag-ship's place would ordinarily be at the head of her own squadron. From the senior flag-ship all orders and signals would be made; and should it become impossible for signalling to be carried on, owing to masts, etc., being shot away, each group of ships would simply watch and follow the movements of their own flag-ship, the Commander-in-Chiefs flag-ship setting the example for her group of ships, and the second in command in his flag-ship following suit. 178 THE NAVY AND ARMY ILLUSTRATED. [March 12tr, 1S17. THE BRITISH FLEET. Photo. F. G. 0- S. GREGORY & CO., Naval Opticians, .;/. Sttand. Copyright.—HUDSOX & ',.E.IRKS. SHIPPING AMMUNITION AND STORES. ERE we see some of the incidents that would attend the setting out of a British Fleet for active service, the ships being ready coaled, and having all hands on board and sea stores taken in, ready for the receipt ot H final sailing orders. -

Royal Navy Exhibit

Royal Navy Concession Rate Letters ROYAL NAVY CONCESSION RATE LETTERS 1795 – 1903 Large Gold & Grand Award Collection 1 Royal Navy Concession Rate Letters INTRODUCING GERALD JAMES ELLOTT 2 Royal Navy Concession Rate Letters Gerald James Ellott, MNZM, RDP, FRPSNZ Gerald is one of New Zealand's leading philatelist and postal historian. By profession he is a Chartered Architect having designed schools in England and working for the NZ Ministry of Works and the Education Department since 1955, and has had his own practice in Auckland for over 50 years, specializing in Education Buildings. Gerald started collecting postage stamps at the tender age of seven and has been passionate about the hobby ever since. Involved with organized philately since coming to New Zealand, he served on the Council of the NZ Philatelic Federation for 32 years, and is still active in their Judging Seminars. He has been awarded the NZ Federation Award of Merit and Award of Honour as well as the coveted Award of Philatelic Excellence. In 1980 Gerald was Chairman of the very successful International Stamp Exhibition, “Zeapex '80” held in Auckland and to date the Zeapex Philatelic Trust has distributed over $500,000.00 to the philatelic fraternity in NZ. Currently a life member of the Royal Philatelic Society of NZ and a past President, he has received all their honours including the Centennial Medal, the Rhodes and Collins Awards. Having started his foray into competitive exhibitions, a Silver Bronze medal for 32 sheets of Chalons, at Sipex (Washington) in 1966, a medal which he treasures as one of the most important, he has formed at least four major collections, two of which have both been in the FIP Championship Class, one of which was awarded the Grand Prix National of the NZ 1990 FIP International Exhibition held in Auckland. -

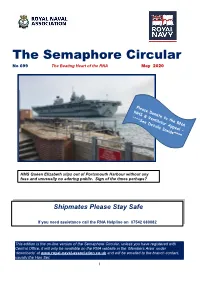

Semaphore Circular No 699 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2020

The Semaphore Circular No 699 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2020 HMS Queen Elizabeth slips out of Portsmouth Harbour without any fuss and unusually no adoring public. Sign of the times perhaps? Shipmates Please Stay Safe If you need assistance call the RNA Helpline on 07542 680082 This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. NHS and Ventilator Appeal 2. Zoom Stuff 3. Sheepdog Wilson 4. Guess the Establishment 5. RNA Clothing and Slops 6. Cenotaph Parade 2020 7. HMS Phoebe Greenies 8. Fleet Transformation 9. Nelson D Day Charity Gin 10. VE Day Commemorations 11. RNA Christmas card Competition 12. VC Series - AB Tuckwell GC 13. RN Veterans Photo Competition 14. The Reunion 15. Missing the RN 16. Answer to Guess the Establishment 17. Joke for the Road Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations NCBA National Charter, Rules and Byelaws Advisor indicates a new or substantially changed entry Contacts Financial Manager 023 9272 3823 [email protected] Finance Assistant -

Jefferson Stereoptics & SADDY STEREOVIEW CONSIGNMENT AUCTIONS ($6.75)

Jefferson Stereoptics & SADDY STEREOVIEW CONSIGNMENT AUCTIONS ($6.75) John Saddy 787 Barclay Road London Ontario N6K 3H5 CANADA Tel: (519) 641-4431 Fax: (519) 641-0695 Website: https://www.saddyauctions.com E-mail: [email protected] AUCTION #18-1 Phone, mail, fax, and on-line auction with scanned images. CLOSING DATES: 9:00 p.m. Eastern Thursday, July 5, 2018 Lots 1 to 411 (Part 1) & Friday, July 6 , 2018 Lots 412 to 830 (Part 2) In the event of a computer crash or other calamity, this auction will close one week later. “BUYER’S PREMIUM CHARGES INCREASE TO 9%” TO ALL OUR STEREOVIEW BIDDERS: PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE’S AN INCREASE IN OUR “BUYER’S PREMIUM CHARGES; IT IS NOW 9%. (We will absorb Paypal charges.) The amount will be automatically added to the invoice. We thank you in advance for your understanding. Your business is very much appreciated. BIDDING RULES AND TERMS OF SALE Paypal ([email protected]). Canadian Bidders: e-transfer accepted Prompt payment is appreciated. 1. All lots sold to the highest bidder. "s.c.mts." = square corner mounts (earlier) 2. Minimum increments: Up to $100, $3., $101 or higher, $10. (Bids only "r.c.mts." = rounded corner mounts (later) even dollars, no change.) 3. Maximum Bids accepted, winning bidder pays no more than one TABLE OF CONTENTS increment above 2nd highest bid. Ties go to earliest bidder. Bidding starts at the price listed. There are no hidden minimums or ADVERTISING 514, 547, 729 reserves.4. YOU WILL SEE TWO BOXES IN WHICH TO PLACE AFRICAN - AMERICAN 45, 48, 50, 85, 152, 544, 558, 583, 668, 669, 708, 715, YOUR BID. -

Australian Naval Personalities

AustrAliAn NavAl PersonAlities lives from the AustrAliAn DictionAry of BiogrAPhy Cover painting by Dale Marsh Ordinary Seaman Edward Sheean, HMAS Armidale Oil on plywood. 49.5 x 64.8cm Australian War Memorial (ART 28160) First published in February 2006 Electronic version updated October 2006 © The Australian National University, original ADB articles © Commonwealth of Australia 2006, all remaining articles This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Announcement statement—may be announced to the public. Secondary release—may be released to the public. All Defence information, whether classified or not, is protected from unauthorised disclosure under the Crimes Act 1914. Defence Information may only be released in accordance with the Defence Protective Security Manual (SECMAN 4) and/or Defence Instruction (General) OPS 13-4—Release of Classified Defence Information to Other Countries, as appropriate. Requests and inquiries should be addressed to the Director, Sea Power Centre - Australia, Department of Defence. CANBERRA, ACT, 2600. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Gilbert, G. P. (Gregory Phillip), 1962-. Australian Naval Personalities. Lives from the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Biography ISBN 0 642 296367 1. Sea Power - Australia. 2. Navies - Australia. 3. Australian - Biography. 4. Australia. Royal Australian Navy. I. Gilbert, G. P. (Gregory Phillip), 1962-. II. Australia. Royal Australian -

Ballyseedy, Tralee, Co.Kerry

BLENNERHASSETT family of BALLYSEEDY, ELM GROVE & ASH HILL in Co.KERRY Blennerhassett Family Tree (BH06_Ballyseedy_B.xlsx) revised July 2014, copyright © Bill Jehan 1968-2014 Thanks to all who have contributed to these pages - please email additions & corrections to: [email protected] CONTINUED FROM page BL 01 of: Blennerhassett of BALLYCARTY & LITTER, Co.Kerry B 01 "heart within a heart" >|>>> John >>>>>>>>>>>>>|>>>Arthur Blennerhassett; of old Ballyseedy Castle & of Tralee (dsp); b.est.c1660; d.7.1.1686 Tralee Castle; Letters of administration 1686 inscribed on keystone of arch Blennerhassett Jr | m.?.3.1677/8; Anne Maynard of Curryglass, Co.Cork above the 1721 foundation stone in (BL 1) b.est.c1630 | NOTE: Two Denny 1st cousins (of Arthur Blennerhassett) from Tralee, married sisters of Anne Maynard Banqueting Hall at Ballyseedy Castle prob. at Ballycarty | Co.Kerry; settled |>>>Col. John >>>>>>>>>>>>>>|>> Mary Blennerhassett; living 1689; died young(?); mentioned in Will of her Foundation stone 1721 at "Ballyseedy Castle", formerly "Elm Grove" at adjoining town- | Blennerhassett | g.mother Elizabeth Denny Blennerhassett but not in 1708 Will of her father land Ballyseedy | (alias 'Hassett) | / | of Ballyseedy |>>>Col. John >>>>>>>>>>>>>|>>>John Blennerhassett >>>>>>>>>>>>>|>> Frances >>>>>>>>>>>|>> Jemmett Browne; of Riverstown, Co.Cork & Arabella House, Ballymacelligott; b.c15.10.1787 ["Cork Evening Post" 15.10.1787]; his g.father Robert | (succeeded 1677) | Blennerhassett Jr, MP | Jr. of Ballyseedy | Blennerhassett | High Sheriff Co.Cork 1816; d.18.2.1850; Will pr.7.8.1850 [PCC]; unm.; succeeded by his brother John Browne BH of Flimby in | / | of Ballyseedy | b.15.6.1715 | b.c1753 | Cumberland had | b.c1665 Co.Kerry; | (succeeded 1708); | / | d.19.10.1824 Bath |>> Rev.