Three Rivers: Protecting the Yukon's Great Boreal Wilderness Peepre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Delta, Yukon Territory, Canada

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Delta, Yukon Territory, Canada. James Murl Mccloy Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mccloy, James Murl, "Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Delta, Yukon Territory, Canada." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1605. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1605 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-252 McCLOY, James Murl, 1934- MORPHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BLOW RIVER DELTA, YUKON TERRITORY, CANADA. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1969 Geography University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Morphologic Characteristics of the Blow River Belta, Yukon Territory, Canada A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by James Murl McCloy B.A., State College at Los Angeles, 1961 May, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research culminating in this dissertation was conducted under the auspices of the Arctic Institute of North America. The major portion of the financial support was received from the United States Army under contract no. BA-ARO-D-3I-I2I4.-G832, "Arctic Environmental Studies." Additional financial assistance during part of the writing stage was received in the form of a research assistantship from the Coastal Studies Institute, Louisi ana State University. -

A Summary of Water Quality Analyses from the Colville River and Other High Latitude Alaskan and Canadian Rivers

A SUMMARY OF WATER QUALITY ANALYSES FROM THE COLVILLE RIVER AND OTHER HIGH LATITUDE ALASKAN AND CANADIAN RIVERS Prepared for North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management P.O. Box 69 Barrow, AK 99523 by ABR, Inc.—Environmental Research & Services P.O. Box 240268 Anchorage, AK 99524 December 2015 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 METHODS ......................................................................................................................................2 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ......................................................................................................2 LITERATURE CITED ....................................................................................................................6 TABLES Table 1. ABR sampled water chemistry results at 4 stations located on the Nigliq Channel of the Colville River, Alaska, 2009–2014. ................................................ 10 FIGURES Figure 1. The location of water chemistry sample collections in the Colville River by ABR, USGS, and NCAR along with important Arctic Cisco fishing locations and Saprolegnia outbreaks, 2009–2015. ..................................................................... 13 Figure 2. The location of water chemistry sample collections in large rivers of Alaska and Canada, 1953–2014..................................................................................................... 14 APPENDICES Appendix A. -

The Peel River

Peel River Water and Suspended Sediment Sampling Program (2002 - 2007) Water quality in the Peel River is generally excellent. The recent sampling carried out in the Peel River above Fort McPherson shows that the water is safe for drinking*, swimming and aquatic life. *After boiling for five complete minutes The Peel River... • Rises in the Oglivie Mountains, Yukon Territory; • Is formed by the confluence of the Blackstone and Ogilvie rivers; • Joins the Mackenzie River approximately 65 km south of Aklavik; • Has a mean annual flow of 675 m3/s, which means that on average 675,000L of water passes by the community of Fort McPherson each second; and, • Contributes 16% of the fine sediment to the Mackenzie Delta each year. This is equal to 20 billion kilograms of sediment! Steven Tetlichi, Fort McPherson Community Liaison and Field Guide Why were samples collected? Samples were collected from the Peel River to: • Learn more about water and suspended sediment in Suspended sediment is the river; the soil (sand, silt, clay, • Contribute to the existing knowledge about water quality in order to track changes over time; organic debris) that • Address community concerns about contaminants in floats in water. water and suspended sediment; and • Support the development of water quality objectives for the Yukon-Northwest Territories Bilateral Waters Agreement. Where and when were samples collected? The Peel River water and suspended sediment samples were collected upstream of Fort McPherson between 8 Mile and the big island. This sampling site has been operated by Environment Canada as part of their water quality network since 1969. -

A Freshwater Classification of the Mackenzie River Basin

A Freshwater Classification of the Mackenzie River Basin Mike Palmer, Jonathan Higgins and Evelyn Gah Abstract The NWT Protected Areas Strategy (NWT-PAS) aims to protect special natural and cultural areas and core representative areas within each ecoregion of the NWT to help protect the NWT’s biodiversity and cultural landscapes. To date the NWT-PAS has focused its efforts primarily on terrestrial biodiversity, and has identified areas, which capture only limited aspects of freshwater biodiversity and the ecological processes necessary to sustain it. However, freshwater is a critical ecological component and physical force in the NWT. To evaluate to what extent freshwater biodiversity is represented within protected areas, the NWT-PAS Science Team completed a spatially comprehensive freshwater classification to represent broad ecological and environmental patterns. In conservation science, the underlying idea of using ecosystems, often referred to as the coarse-filter, is that by protecting the environmental features and patterns that are representative of a region, most species and natural communities, and the ecological processes that support them, will also be protected. In areas such as the NWT where species data are sparse, the coarse-filter approach is the primary tool for representing biodiversity in regional conservation planning. The classification includes the Mackenzie River Basin and several watersheds in the adjacent Queen Elizabeth drainage basin so as to cover the ecoregions identified in the NWT-PAS Mackenzie Valley Five-Year Action Plan (NWT PAS Secretariat 2003). The approach taken is a simplified version of the hierarchical classification methods outlined by Higgins and others (2005) by using abiotic attributes to characterize the dominant regional environmental patterns that influence freshwater ecosystem characteristics, and their ecological patterns and processes. -

Ecosystems of the Peel Watershed: a Predictive Approach to Regional Ecosystem Mapping

Ecosystems of the Peel Watershed: A Predictive Approach to Regional Ecosystem Mapping Prepared for: Peel Watershed Planning Commission Ecosystems of the Peel Watershed: A Predictive Approach to Regional Ecosystem Mapping Prepared for: Peel Watershed Planning Commission Prepared by: John Meikle & Marcus Waterreus, Environment Yukon Ecosystems of the Peel Watershed: A Predictive Approach to Regional Ecosystem Mapping TR-08-01 John Meikle & Marcus Waterreus, Fish & Wildlife Branch Director, Fish & Wildlife Branch Recommended citation: Meikle, John C. and Marcus B. Waterreus. 2008. Ecosystems of the Peel Watershed: A Predictive Approach to Regional Ecosystem Mapping. Yukon Fish and Wildlife Branch Report TR-08-01. 66 pp. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Ecosystems of the Peel Watershed: A predictive approach to regional ecosystem mapping/John C. Meikle and Marcus B. Waterreus. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 1-55362-348-7 © 2008 Department of Environment, Government of Yukon You may use the information in this report for education and information purposes. If you want to use any portion of this report in scientific publications, you must have permission in writing from the Department of Environment, Government of Yukon, Box 2703, Whitehorse, Yukon, Y1A2C6 Printed on recycled paper Printed and bound in Canada Cover Photo: Wetland in the Hart River Basin, Peel Watershed, Yukon Photo credit: Environment Yukon (J. Meikle) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements The conceptual foundation for this work was based on the North Yukon regional predictive ecosystem map, developed in 2005 by Shawn Francis and Jeff Hamm (Yukon Land Use Planning Council), and John Meikle (Fish & Wildlife Branch, Environment Yukon). Revisions made to the Yukon portion of the National Ecological Framework in 2004 by Nancy Steffen (Gartner Lee Ltd.), Karen McKenna (Cryogeographics), John Meikle and Shawn Francis provided the base on which this ecosystem interpretation was built. -

Investigating the Spatial Distribution of Water Levels in the Mackenzie Delta Using Airborne Lidar

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. (2011) Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/hyp.8167 Investigating the spatial distribution of water levels in the Mackenzie Delta using airborne LiDAR C. Hopkinson,1*N.Crasto,1,2 P. Marsh,3 D. Forbes4 and L. Lesack5 1 Applied Geomatics Research Group, Centre of Geographic Sciences, Lawrencetown, Nova Scotia 2 Geology Department, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia 3 National Water Research Institute, Environment Canada, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan 4 Geological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Bedford, Nova Scotia 5 Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia Abstract: Airborne light detection and ranging (LiDAR) data were used to map water level (WL) and hydraulic gradients (υH/υx) in the Mackenzie Delta. The LiDAR WL data were validated against eight independent hydrometric gauge measurements and demonstrated mean offsets from 0Ð22 to C0Ð04 m (<0Ð11). LiDAR-based WL gradients could be estimated with confidence over channel lengths exceeding 5–10 km where the WL change exceeded local noise levels in the LiDAR data. For the entire Delta, the LiDAR sample coverage indicated a rate of change in longitudinal gradient (υ2H/υx) of 5Ð5 ð 1010 mm2; therefore offering a potential means to estimate average flood stage hydraulic gradient for areas of the Delta not sampled or monitored. In the Outer Delta, within-channel and terrain gradient measurements all returned a consistent estimate of 1 ð 105 mm1, suggesting that this is a typical hydraulic gradient for the downstream end of the Delta. For short reaches (<10 km) of the Peel and Middle Channels in the middle of the Delta, significant and consistent hydraulic gradient estimates of 5 ð 105 mm1 were observed. -

Thawing of Massive Ground Ice in Mega Slumps Drives Increases in Stream Sediment and Solute flux Across a Range of Watershed Scales S

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH: EARTH SURFACE, VOL. 118, 681–692, doi:10.1002/jgrf.20063, 2013 Thawing of massive ground ice in mega slumps drives increases in stream sediment and solute flux across a range of watershed scales S. V. Kokelj,1 D. Lacelle,2 T. C. Lantz,3 J. Tunnicliffe,4 L. Malone,5 I. D. Clark,5 and K. S. Chin1 Received 6 June 2012; revised 7 March 2013; accepted 14 March 2013; published 20 May 2013. [1] Ice-cored permafrost landscapes are highly sensitive to disturbance and have the potential to undergo dramatic geomorphic transformations in response to climate change. The acceleration of thermokarst activity in the lower Mackenzie and Peel River watersheds of northwestern Canada has led to the development of large permafrost thaw slumps and caused major impacts to fluvial systems. Individual “mega slumps” have thawed up to 106 m3of ice-rich permafrost. The widespread development of these large thaw slumps (up to 40 ha area with headwalls of up to 25 m height) and associated debris flows drive distinct patterns of stream sediment and solute flux that are evident across a range of watershed scales. Suspended sediment and solute concentrations in impacted streams were several orders of magnitude greater than in unaffected streams. In summer, slumpimpactedstreamsdisplayeddiurnalfluctuations in water levels and solute and sediment flux driven entirely by ground-ice thaw. Turbidity in these streams varied diurnally by up to an order of magnitude and followed the patterns of net radiation and ground-ice ablation in mega slumps. These diurnal patterns were discernible at the 103 km2 catchment scale, and regional disturbance inventories indicate that hundreds of watersheds are already influenced by slumping. -

Report on the Peel River and Tributaries, Yukon and Mackenzie

C!HM ICIUIH Microfiche Collection de Series microfiches ({Monographs) (monographles) Canadian Instituta for Historical Microroproductiona / Institut Canadian da microraproductions hittoriquas Technical and BiDliographic Notes / Notes techniques et bibliographiques The Institute has attempted to otrtain the t)est original L'Institut a microfilm^ le meilleur exemplaire qu'il lul a copy available for filming. Features of this copy which M possible de se procurer. Les details de cet exem- may be bibllographically unique, which may alter any of plaire qui sont peut-4tre uniques du point de vue bibii- the images in the reproduction, or which may ographlque, qui peuvent modifier une image reproduite, significantly change the usual method of filming are ou qui peuvent exiger une nfKXilfication dans la mtKho- checked below. de normale de flimage sont indiqute ci-dessous. Coloured covers / Coloured pages / Pages de couleur I I D Couverture de couleur Pages dantaged / Pages endommagdes I I Covers damaged / D Couverture endommagte Pages restored and/or laminated / Pages restaur^es ei/ou peliicul^es Covers restored and/or laminated / D Couverture restaur^e et/ou pelliculte r~pf Pages discoloured, stained or foxed/ |j^ Pages d^coiortes. tachetdes ou piques Cover title missing / Le titre de couverture manque Pages detached / Pages d^tach^s I I 3 Coloured maps / Cartes gtegraphiques en couleur 1^1 Showthrough / Transparence Coloured inl( (i.e. other than blue or blade) / D Encre de couleur (i.e. autre que bleue ou noire) I Quality of print varies / I -

The Mackenzie River Basin

ROSENBERG INTERNATIONAL FORUM: THE MACKENZIE RIVER BASIN JUNE 2013 REPORT OF THE ROSENBERG INTERNATIONAL FORUM’S WORKSHOP ON TRANSBOUNDARY RELATIONS IN THE MACKENZIE RIVER BASIN The Rosenberg International Forum on Water Policy On Behalf of The Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation ROSENBERG INTERNATIONAL FORUM: THE MACKENZIE RIVER BASIN June 2013 REPORT OF THE ROSENBERG INTERNATIONAL FORUM’S WORKSHOP ON TRANSBOUNDARY RELATIONS IN THE MACKENZIE RIVER BASIN 4 Rosenberg International Forum The MACKENZIE RIVER BASIN The Mackenzie River Basin 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE EXISTING SCIENCE & SUMMARY SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE: 06 22 WORRISOME SIGNALS AND TRENDS INTRODUCTION CANADA’s COLD 07 AMAZON: 27 THE MACKENZIE THE STRUCTURE SYSTEM AS A UNIQUE & OBJECTIVES OF GLOBAL RESOURCE 08 THE FORUM NEW KNOWLEDGE SETTING NEEDED THE STAGE: 29 10 THE MACKENZIE SYSTEM MANAGING THE MACKENZIE THE MACKENZIE 30 SYSTEM: 18 THE EFFECTS CONCLUSIONS OF COLD ON HYDRO-CLIMATIC 35 CONDITIONS 38 REFERENCES 6 Rosenberg International Forum EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he Mackenzie River is the largest north- between the freshwater flows of the Mackenzie governance structure for the Basin. flowing river in North America. It is the and Arctic Ocean circulation. These are One major recommendation is that the longest river in Canada and it drains a thought to contribute in important ways to the Mackenzie River Basin Board (MRBB), T watershed that occupies nearly 20 per stabilization of the regional and global climate. originally created by the Master Agreement, be cent of the country. The river is big and complex. In this respect, the Mackenzie River Basin must reinvigorated as an independent body charged It is also jurisdictionally intricate with tributary be viewed as part of the global commons. -

Alaska Those Set out in Federal Or Yukon Laws

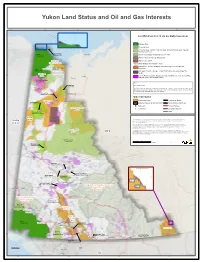

Yukon Land Status and Oil and Gas Interests 145°W 140°W 135°W 130°W 125°W 120°W 70°N B e a u 70°N f o r t S Land Withdrawn from Oil and Gas Rights Dispositions e a Y-EL-329 Arctic Ocean Pattern 2 Y-EL-329 National Park Pattern 7 Territorial Park Protected Area, Habitat Protection Area, National Wildlife Area, Special Management Area Hershel Island Ivvavik Tuktoyaktuk Territorial Park Yukon North Slope Withdrawal M.O. 2010/09 National Park Active Yukon Oil and Gas Dispositions Beaufort - Active Coal Leases Mackenzie Basin Yukon First Nations Settlement Lands Category A - Yukon First Nation has ownership of the surface and Yukon North Slope subsurface Vuntut Withdrawal National Park Category B and Fee Simple - Yukon First Nation has ownership of the surface 68°N Old Crow 68°N Basin Inuvik Interim Protected Lands (lands protected to facilitate the settlement of First Aklavik Nations without ratified land claims) Old Crow Flats Area Protected Area Note 1 Dàadzaii Vàn Interim Withdrawal Old Crow Territorial Park The Government of Yukon has temporarily suspended the issuance of new oil and gas rights in the Whitehorse Trough Basin and in the Traditional Territories of First Nations without ratified Land Claims (Ross River Dena Council, Liard and White River First Nations) Ch'ihilii Chìk Fort McPherson Habitat Protection Area Other Information Eagle Plain Sedimentary basin International Border Fishing Branch Adjoining Federal Oil and Gas Rights Territorial/Provincial Border Ecological Reserve Basin ^! Major City Primary Highway Peel Plateau - Plain !k Community Secondary Highway Basin Road Fishing Branch 66°N Wilderness Preserve 66°N Kandik Basin This map identifies those Yukon lands which may be subject to terms and conditions of use and access other than Alaska those set out in federal or Yukon laws. -

The Peel Decision and Beyond

The Peel Decision and Beyond MARCH 21, 2018 WESTMARK HOTEL > WHITEHORSE MORNING 8-8:30AM Breakfast: Coffee, Muffins 8:30-8:45AM Call to Order Welcoming: Joe Copper Jack Opening Prayer: Julia Broeren, Ta’an Kwäch’an Elder Event Introduction: Michael Pealow, Blair Hogan 8:45 – 9AM Why This Gathering Was Called: Pearl Callaghan, YLUPC Chair 9-9:15AM Review of Peel Planning Process: Ron Cruikshank, Director, YLUPC 9:15– 11AM Implication of the Supreme Court of Canada’s Peel Watershed Ruling: First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk vs Yukon, 2017 SCC 58 Moderated by Gary W. Whittle, Whittle & Company, Lawyers Legal Panel: John Olynyk, Lawson Lundell, LLP, Mara Pollock, Pollock Law, Kyle Carruthers, Tucker and Carruthers Opening remarks by panel members Moderator’s questions to panel members 10:15 Break 10:30 – 11:00 Audience questions to panel members 11AM-12PM Break-out Session Topic: Supreme Court Ruling 2017 SCC 58 Peel Watershed Small group circle discussions 12-1PM Lunch – Chicken Souvlaki, Rice, Salad, with music by Jerry Alfred Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources, Ranj Pillai lunch time address The Peel Decision and Beyond MARCH 21, 2018 WESTMARK HOTEL > WHITEHORSE AFTERNOON 1-1:30PM Chapter 11 Implementation: Progress and Challenges and Potential Solutions (Ron Cruikshank, YLUPC and Lesley Cabott, Stantec) Questions & Answers 1:30-2:30PM A Planning Framework for the Yukon? Introduction: A Land Claim Based Planning Framework for the Yukon? Ron Cruikshank and Amy Ryder, Ryder Communications Alberta’s Land Use Planning Framework: Continually Improving -

Water Quality and Quantity in The

Water Quality and Quantity in the NWT WaterT day Water is life The Northwest Territories (NWT) has an abundance In recent years, Northerners have been paying more of freshwater. This water is essential to ecosystem attention to the state of our water quality and quantity. health, as well as to the social, cultural and economic With increasing water resource pressures on a regional, well-being of territorial residents. national and international level, residents Northerners rely on water for sustenance, Water is considered by are recognizing that actions need to be recreation, and transportation. Major taken now to ensure our water resources many Aboriginal people water uses in the NWT include municipal are sustained for future generations. consumption, industrial development, to be a heart – Environmental monitoring and research such as mining, oil and gas and activities provide a foundation for making giving life to people, hydroelectric power production. sound decisions about water resources in For Aboriginal people, who wildlife, fish and plants. the NWT. make up approximately 48% of the territory’s population, water has intrinsic cultural, spiritual, and historical value. Water is considered by many Aboriginal people to be a heart – giving life to people, wildlife, fish and plants. “Water level and Where does our water go? flow data provided The majority of rivers and lakes within the NWT are by the Water Survey situated within the Mackenzie River watershed, Canada’s of Canada largest river basin. The Slave River is the dominant inflow to Great Slave Lake, accounting for approximately 77% hydrometric gauges of total inflows. The Taltson, Lockhart and Hay rivers on the Hay River together contribute approximately 11% of inflows, while Photo: D.