Naples, Centre of Campania Felix, Different Points of View, Changing Perspectives Through the Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lucrezia Paolina, Salvator Rosa, and Feminist Art History Linda C

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2010, vol. 5 “Lady without Equal”: Lucrezia Paolina, Salvator Rosa, and Feminist Art History Linda C. Hults It is we women, said Leonora, who lighten men’s burden of worries. When we take charge of household affairs. , we take over a part of their work, overseeing the whole household. And it’s certainly true that a man can never really find true domestic contentment and harmony without the fond companionship of a woman, . without someone to look after him and take care of all his needs, and to share all the good times and the bad times with him. —Moderata Fonte, The Worth of Women, c. 1592 Keeping House, Making Art Even when they did not make art, early modern women contributed to its production, whether as models, female kin, mistresses, or wives. Marriage itself was often a sign of professional status for the early modern male artist, although its legal and social benefits for men varied.1 Artists’ wives might keep accounts, prepare materials, sell works, or run large households (like Rubens’s in Antwerp), sustaining master, pupils, and assistants and offering hospitality to visitors and patrons.2 Margaret Lemon, van Dyck’s cultivated mistress, ran his residence at Blackfriars between 1632 and 1639, also modeling for portraits and mythological and religious images in which her personality and relationship with the artist became part of the artistic content.3 Similarly, Rembrandt’s relationship with Hendrickje Stoffels 11 EMW_2010.indb 11 7/15/10 7:57 AM 12 EMWJ 2010, vol. 5 Linda C. -

John H. Knapp Diary 1869-70.Pdf

DIARY OF J. H. KNAPP OF MENOMONIE DUNN CO. WIS. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Transcribed by Marge Kunkel, Archives Assistant August 19, 1869 At 7 ½ oclk A.M. my son Henry & I started on a trip to Europe. My sister Almeda accompanied us – she only intends going as far as Fort Madison, Iowa. We took the little steamboat Pete Wilson at Dunnville and arrived in Reads Landing Minn. At 1 ½ oclk P.M. At 10 ½ P.M. the Northern Line Steamer “Minneapolis” T.B. Rhodes Capt Wm. W. Vandyke clerk came down from St Paul & we took passage for DuBuque Iowa. August 20th At 9 ½ P.M. we arrived in DuBuque. We went to the house of H. L. Stout Esq & found a cordial welcome. August 21st The day was warm. In the afternoon we rode out around the City with Mr. Stout. I went to the Lumber Yard Steamer Annie Girdon &c&c Sunday 22d Went to church twice to day with Mr. & Mrs. Stout. In the forenoon we heard a sermon from a stranger at the Cong. Church from the text Matt 16-26- For what shall it profit &c. In the evening we went to hear Dr. Speers at the 2d Pres. Ch. Text 2d Kings. “Is it well with thee” Monday 23d We waited all day for a boat to go down the river. No boat came much to our disappointment. We expected the City of St Paul but she was reported on the way at La Crosse for repairs. The day proved to be a very hot one. -

Piranesi's Arguments in the Carceri

ITU A|Z • Vol 15 No 3 • November 2018 • 29-39 Piranesi’s arguments in the Carceri Fatma İpek EK [email protected] • Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Yaşar University, İzmir, Turkey Received: November 2017• Final Acceptance: September 2018 Abstract Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) is an important Italian architect with his seminal theses in the debates on the ‘origins of architecture’ and ‘aesthetics’. He is numbered foremost among the founders of modern archaeology. But Piranesi was misinterpreted both in his day and posthumously. One of the most important vectors of approach yielding misinterpretation of Piranesi derived from the phe- nomenon comprising the early nineteenth-century Romanticist reception of Pi- ranesi’s character and work. Therefore, the present study firstly demonstrates that such observations derive not from an investigation of the work itself, nor from an appraisal of the historical context, but owe to the long-standing view in western culture that identifies the creator’s ethos with the work and interprets the work so as to cohere with that pre-constructed ethos. Thus the paper aims at offering a new perspective to be adopted while examining Piranesi’s works. This perspective lies within the very scope of understanding the reasons of the misinterpretations, the post-Romanticist perception of the ‘artist’, and Piranesi’s main arguments on the aesthetics, origins of architecture, and law. Keywords Carceri series, Eighteenth century discussions, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Post- doi: 10.5505/itujfa.2018.21347 doi: romanticist interpretation, Romanticist perception. 30 1. Introduction ethos. In fact, the pervasive descrip- In the architectural, historical, and tion of Piranesi’s work as cited above archaeological context of the eighteenth goes hand in hand with the descrip- century, Italian architect Giovanni Bat- tion of the biographical character as tista Piranesi (1720-1778) played an im- ‘obscure’ and ‘perverse’.3 For Piranesi’s portant role. -

Me. in the First Place, I Did Not Subscribe for M Y Heirs And

To LADY OSSORY 15 DECEMBER 1786 547 me. In the first place, I did not subscribe for my heirs and executors,1* as it would have been, when the term of completion is twelve years henceJ4—but I am not favourable to sets of prints for authors: I scarce know above one well executed, Coypell's Don Quixote1*—but mercy on us I Our painters to design for Shakespeare! His commenta tors have not been more inadequate. Pray, who is to give an idea of Falstaffe, now Quin is dead?—and then Bartolozzi,16 who is only fit to engrave for the Pastor fido/7 will be to give a pretty enamelled fan-mount18 of Macbeth!1* Salvator Rosa might, and Piranesi20 might dash out Duncan's Castle—but Lord help Alderman Boydell21 and the Royal Academy l23 work, Messieurs Boydell also intend to HW's appreciation of Bartolozzi's success publish by subscription a series of large in the pastoral tradition, see MASON i. 386. and capital prints after pictures to be im 18. For Bartolozzi's fan mounts, see mediately painted by the following artists A. de Vesme and A. Calabi, Francesco ... Sir Joshua Reynolds [and twelve Bartolozzi, Milan, 1928, pp. 551-6, Nos others named] . To be engraved by 2216-26. Mr Bartolozzi [and eight others named]. 19. Bartolozzi engraved only one pic As soon as they have all been engraved ture, by William Hamilton, for the large they will be hung up in a gallery, built prints: Plate XXXII, for Twelfth Night, on purpose, and called the Gallery of V. -

California State University, Northridge Giovanni

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI AND THE ROMANTIC RUIN IN FRENCH LITHOGRAPHY A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Cynthia Lee Kimble January 1984 The Thesis of Cynthia Lee Kimble is approved: Birgitta Lindros Wohl, Ph.D. Kenon Breaze~le, Ph.D. California State University, Northridge ii I would like to extend my gratitude to the members of my committee, especially to Louise Lewis for her enthusiasm and understanding, and to Dr. Birgitta Wohl, for her friendship and guidance. I also want to express my appreciation to my family, for their loyal support and encouragement throughout the duration of this project. Last, but not least, I would like to say a special "thank you" to my typist, Ann Witkower, for her expertise in preparing the final draft of this thesis. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments . .iii List of Plates •• . • • v Abstract. • • • • • •• xvii Introduction. • • 1 Chapter 1: The Forerunners of the Romantic Ruin in Print • • • • • . 4 Chapter 2: Piranesi and the Ruins of Rome. • 37 Chapter 3: Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l'ancienne France and Piranesi •••••• 91 Conclusion. • • • • • 0 • • • • • • • • • • • • .155 Bibliography. • 1 61 Appendices. • • • • • •••••• • 1 73 A Selected List of Piranesi's Works B Volumes of Voyages pittoresgues et romantigues dans l'ancienne France Plates. • • • • • 1 76 iv LIST OF PLATES Plate Page 1 • Fra Francesco Colonna. The Polyandrion, woodcut. Hypnerotomachia Polifili, 1499. Cooper Union Museum, New York. Source: Paul Zucker. Fascination of Decay: Ruins, Relic, Symbol, Ornament. Ridgewood, N.J.: Gregg Press, 1968, p. -

Curriculum Vitae

Guerrilla di civiltà| a socially advantageous performance Bio CleaNap was founded in 2011 as a proposal of socially useful performance. Together, we aim to create events of urban creativity. We started with the smart-mob to make Piazza Clean to proactively demonstrate our sense of community by cleaning up the city squares. Today we are predominantly an association that deals with sustainability and social innovation. 1 Main Projects Since 2011, we are promoters and partners of the Italian movement Let’s do it! World, and organization founded in Estonia in 2008 with the intention of making the ambitious project to clean up their own country in a single day. The network has expanded globally, so every year, each national delegation is organizing a major event of cleaning. The clean up day, with the help of all forces gathered, tries to emphasize the importance of preservation of the common good and sustainable development. Since 2011, we are partners of the Ferrara Buskers Festival Eco Festival. With this project the aim is to create a collection within the festival through the principals of collection points by the eco- assistants, who are people from the Naples CleaNap project. The task of the eco-assistant is directing viewers to a proper separation of waste in order to achieve an effective collection. Another task is assisting the operators of the Hera Group in the management of the collection. In 2013, the Ferrara Buskers Festival has received the prestigious Prix Cultural “In Verde”, thanks to the project eco festival. Stopbiocidio. We are part of #fiumeinpiena, a peaceful movement and non partisan, founded and formed by young people. -

Bernini Sponsorship

Bernini and the Roman Baroque Masterpieces from the Palazzo Chigi in Ariccia June 26 to September 19, 2021 Tis exciting exhibition of Baroque art marks the museums’s frst large-scale exhibition of Old Master paintings and artworks since 1965. Te more than 50 works include dramatic canvasses depicting scenes from mythology, the Bible, and history. Te exhibition examines the infuence of Baroque master Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) on the artistic climate of Rome and beyond through the collection of the Chigi family’s historic Palazzo located about 16 miles outside of Rome. Organized by Glocal and traveled by International Art and Artists, this landmark exhibition will share rare European masterworks from a historic collection with the Hagerstown community and the wider region. Become a part of this blockbuster exhibition by sponsoring an object in the show. Sponsors help us to cover the costs of mounting ambitious exhibitions like this and receive recognition with their object throughout the presentation of the exhibition. Choose your favorite object, and fll out the sponsorship form or contact Development Director Wallace Lee for more information: [email protected] or 301-739-5727. $2,000 Level Giovan Battista Gaulli (Baciccio) Giuseppe Cesari (Cavelier d’Arpino) Self Portrait, 1668 Orphyeus & Eurydice, 1620-25 Oil on canvas Oil on canvas 35 1/4 x 29 7/8 in. 55 1/8 x 73 1/4 in. Carlo Marrati (Maratta) and Mario Nuzzi (Mario de’Fiori) Giacinto Brandi Summer, 1658-59 Lot & His Daughters, 1670-75 Oil on canvas Oil on canvas 75 3/4 x 104 1/8 in. -

Salvator Rosa in French Literature: from the Bizarre to the Sublime

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Studies in Romance Languages Series University Press of Kentucky 2005 Salvator Rosa in French Literature: From the Bizarre to the Sublime James S. Patty Vanderbilt University Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/srls_book Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Preface i Salvator Rosa in French Literature ii Preface Studies in Romance Languages John E. Keller, Editor Preface iii Salvator Rosa in French Literature From the Bizarre to the Sublime James S. Patty THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY iv Preface Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2005 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patty, James S. -

Naples Metro Line 1 Vanvitelli-Dante Section Urban Railway Project Italy

Ex post evaluation of major projects supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund between 2000 and 2013 Naples Metro Line 1 Vanvitelli-Dante Section Urban Railway Project Italy EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Directorate Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Unit Evaluation and European Semester Contact: Jan Marek Ziółkowski E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Ex post evaluation of major projects supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund between 2000 and 2013 Naples Metro Line 1 Vanvitelli-Dante Section Urban Railway Project Italy Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy 2020 EN Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). Manuscript completed in 2018 The European Commission is not liable for any consequence stemming from the reuse of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 ISBN 978-92-76-17420-2 doi: 10.2776/93616 © European Union, 2020 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). Ex post evaluation of major projects supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Fund between 2000 and 2013 This report is part of a study carried out by a Team selected by the Evaluation Unit, DG Regional and Urban Policy, European Commission, through a call for tenders by open procedure No. -

Bernini & the Roman Baroque

BERNINI & THE ROMAN BAROPAINTINGS FROM PALAZZOQUE CHIGI IN ARICCIA TRAVELING EXHIBITION SERVICE he term Baroque connotes an abundance of detail, a sense of irregularity, and a sort of eccentric redundancy—all hallmarks of an extraordinary generation of Tartists who converged in Rome at the dawn of the seventeenth century. This artistic style became a cultural phenomenon, spreading concurrently from Naples to Venice, Vienna to Prague, and Bohemia to St. Petersburg, finally assuming its full global dimensions when it reached the Americas. Bernini and the Roman Baroque: Paintings from Palazzo Chigi in Ariccia explores the genesis of this one-of-a-kind artistic movement. Through a selection of 55 works from 40 artists, this exhibition illuminates Bernini’s influence and explores how it resonated across the Baroque movement. 1 1. Carlo Maratti, called “Il Maratta,” and Mario Nuzzi, called “Mario del Fiori”, The Summer, 1658-59, oil on canvas, Palazzo Chigi, Ariccia. 2 BERNINI AND THE ROMAN BAROQUE TRAVELING EXHIBITION SERVICE 3 INTRODUCTION At the beginning of the seventeenth century, artists Bernini and the Roman Baroque comprehensively maps definitively set aside the Caravaggesque model for a the rich spectrum of genres and pictorial styles that more transversal dialogue between the real and the characterize Baroque aesthetics. Its many luminous supernatural, the superfluous and the necessary. After examples of these diverse categories—not only history the death of the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, painting but also alternative genres such as portraiture, the debate between “naturalists” and “classicists” self-portraiture and landscaping, as well as preparatory (respectively, followers of the styles of Caravaggio sketches used for large decorative frescoes—epitomize and Annibale Carracci) originated a new figurative Baroque’s ultimate goal of elevating the viewer in mind language, namely the “Baroque,” which found in Gian and soul, communicating the moral and spiritual messages Lorenzo Bernini its undisputed protagonist. -

Salvator Rosa's Democritus and Diogenes in Copenhagen

6/3/2018 Salvator Rosa’s Democritus and Diogenes in Copenhagen | Perspective P E R S P E C T I V E Salvator Rosa’s Democritus and Diogenes in Copenhagen Can Salvator Rosa’s paintings of Democritus and Diogenes be seen as reections of the artist’s self-image as a Stoic painter-philosopher and of his endeavour to create sublime art? is complicated matter is elucidated in the present article. By Eva de la Fuente Pedersen Published March 2017 R E S U M É e article places Rosa’s two paintings of philosophers within a historical context, demonstrating how their subject matter and formal devices bring together and expose a range of important themes in seventeenth-century art theory. e question of the sublime is linked to the connection between the aesthetic and the ethical in the artist and the work of art, to the melancholic temperament and to the concept of genius as it appeared within the art theoretical context of the day. e article shows that the two philosopher-paintings may have been included amongst what Salvator Rosa himself regarded as sublime motifs. ey can be interpreted as a public launch and presentation of the artist’s new perception of the artist self, which incorporated multiple identities: Stoic philosopher, poet, satirist and painter of ethical-moral (sublime) inventions. A R T I C L E Ma nell’ antichità non vo’ ingolfarmi. Mira, come danno aura al Buonarruoti Non men le carte, che le tele, e I marmi. Se i libri del Vasari osservi e noti, http://perspective.smk.dk/en/salvator-rosas-democritus-and-diogenes-copenhagen 1/35 6/3/2018 Salvator Rosa’s Democritus and Diogenes in Copenhagen | Perspective Vedrai che de’ pittori i più discreti Son per la poesia celebri e noti. -

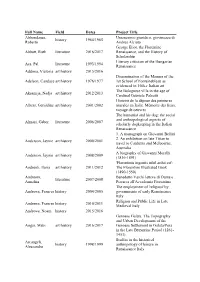

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Roberto History 1964

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Umanesimo giuridico, giovinezza di history 1964/1965 Roberto Andrea Alciato George Eliot, the Florentine Abbott, Ruth literature 2016/2017 Renaissance, and the History of Scholarship Literary criticism of the Hungarian Acs, Pal literature 1993/1994 Renaissance Addona, Victoria art history 2015/2016 Dissemination of the Manner of the Adelson, Candace art history 1976/1977 1st School of Fontainebleau as evidenced in 16th-c Italian art The Bolognese villa in the age of Aksamija, Nadja art history 2012/2013 Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti Histoire de la dépose des peintures Albers, Geraldine art history 2001/2002 murales en Italie. Mémoire des lieux, voyage de oeuvres The humanist and his dog: the social and anthropological aspects of Almasi, Gabor literature 2006/2007 scholarly dogkeeping in the Italian Renaissance 1. A monograph on Giovanni Bellini 2. An exhibition on late Titian to Anderson, Jaynie art history 2000/2001 travel to Canberra and Melbourne, Australia A biography of Giovanni Morelli Anderson, Jaynie art history 2008/2009 (1816-1891) 'Florentinis ingeniis nihil ardui est': Andreoli, Ilaria art history 2011/2012 The Florentine Illustrated Book (1490-1550) Andreoni, Benedetto Varchi lettore di Dante e literature 2007/2008 Annalisa Petrarca all'Accademia Fiorentina The employment of 'religiosi' by Andrews, Frances history 2004/2005 governments of early Renaissance Italy Religion and Public Life in Late Andrews, Frances history 2010/2011 Medieval Italy Andrews, Noam history 2015/2016 Genoese