The Representation of Philosophers in the Art of Salvator Rosa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Logic of Desire

Alexis Turner Indiana University 03.28.2013 Presented at the annual conference for the Western Political Science Association Draft. Please do not cite or distribute without permission The Logic of Desire In ancient Greek thought, which had not yet formally theorized a mathematical concept of zero, the idea of nothing or lack nonetheless held a prominent place, perhaps most fully articulated through eros: desire. Or, as we more gently tend to translate it in English, love. This is an unfortunate softening, for the Greeks understood all too well that to play with love is to play with fire. Such pyrotechnics do not require the abandonment of reason, contrary to most common readings – just as we can admire jaguars, canyons, Siren songs, and other beautiful things without being witless enough to throw ourselves headlong into them, so we can flirt with desire without being consumed. This paper explores the possibility that refusing nothing – refusing to live with desire – is the fundamental error that sits at the heart of The Republic. If I am not entirely mistaken, the Socratic notion of desire is a deeply logical one deployed as a response to, and critical of, question-begging elements inherent in positive declarations derived from a reasoning process based wholly essentialist either/or oppositions. If so, the problem shifts from one of authoritative, unidirectional truth to one of diplomacy, tactics, and strategy. Truth has not disappeared, but it becomes enmeshed in relations between people and depends on the exercise of judgment, restraint, and friendship. Starting with nothing brings us back to politics. Is the modern world really so disenchanted as we are continually being told? The claim resonates, and yet trends in modern photography indicate that things are practically fetishized, each object lovingly isolated and focused on in macro-miniature, each of its colors and curves fondled by the camera. -

Lucrezia Paolina, Salvator Rosa, and Feminist Art History Linda C

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2010, vol. 5 “Lady without Equal”: Lucrezia Paolina, Salvator Rosa, and Feminist Art History Linda C. Hults It is we women, said Leonora, who lighten men’s burden of worries. When we take charge of household affairs. , we take over a part of their work, overseeing the whole household. And it’s certainly true that a man can never really find true domestic contentment and harmony without the fond companionship of a woman, . without someone to look after him and take care of all his needs, and to share all the good times and the bad times with him. —Moderata Fonte, The Worth of Women, c. 1592 Keeping House, Making Art Even when they did not make art, early modern women contributed to its production, whether as models, female kin, mistresses, or wives. Marriage itself was often a sign of professional status for the early modern male artist, although its legal and social benefits for men varied.1 Artists’ wives might keep accounts, prepare materials, sell works, or run large households (like Rubens’s in Antwerp), sustaining master, pupils, and assistants and offering hospitality to visitors and patrons.2 Margaret Lemon, van Dyck’s cultivated mistress, ran his residence at Blackfriars between 1632 and 1639, also modeling for portraits and mythological and religious images in which her personality and relationship with the artist became part of the artistic content.3 Similarly, Rembrandt’s relationship with Hendrickje Stoffels 11 EMW_2010.indb 11 7/15/10 7:57 AM 12 EMWJ 2010, vol. 5 Linda C. -

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

On the Pleasure of Feasting During the Polish Renaissance

Dawid Barbarzak Dawid Barbarzak The Humanist at the Table: On the Pleasure of Feasting during the Polish Renaissance Izvorni znanstveni rad Research paper UDK 17.036.1:7.034>(438) https://doi.org/10.32728/tab.17.2020.1 In this paper, an attempt is made to present the phenomenon of humanist banquets in the culture of the Polish Renaissance in light of the Epicurean category of pleasure (voluptas). Sources analysed in the paper include works of Polish poetry from authors such as Filippo Buonaccorsi „Callimachus”, Conrad Celtis, Jan Kochanowski, Jan Dantyszek „Dantiscus”, Klemens Janicki „Ianitius”, and the work of Łukasz Górnicki Dworzanin polski (Castiglione’s adaptation of Corteg- giano). The texts are compared to selected ancient sources (especially Horace, Epicurus, Lucretius and Pliny the Elder) with the aim of prov- ing that Renaissance humanists imitated the style of philosophical and literary symposia. In the paper, the wider context of this cultural transformation in the context of Renaissance discoveries and printed editions of ancient texts related to Epicurean and Platonic philosophy or the ancient culture of eating is also presented, which could have first inspired Italian, and later also Polish humanists, to adopt this new form of philosophical and literary banquets. Key words: humanist banquet, convivium, symposium, Epicureanism, pleasure, eating In ancient ethical philosophy there were two movements which emphasized the category of pleasure in a special way: hedonism and Epicureanism. The founder of the former, Aristippus of Cyrene, led a luxurious life in Athens and Sicily, claiming that seeking pleasant experiences is more important than reason or deeds. Some anecdotes 21 Tabula 17 Zbornik skupa Kultura Mare internum about his gluttony have survived.1 The philosopher emphasized that having money is not the goal, and that it should be spent for pleasure: To one who reproached him with extravagance in catering, he replied, „Wouldn't you have bought this if you could have got it for three obols?” The answer being in the affirmative. -

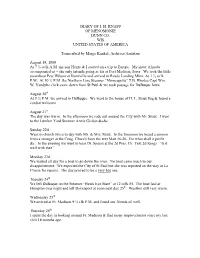

John H. Knapp Diary 1869-70.Pdf

DIARY OF J. H. KNAPP OF MENOMONIE DUNN CO. WIS. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Transcribed by Marge Kunkel, Archives Assistant August 19, 1869 At 7 ½ oclk A.M. my son Henry & I started on a trip to Europe. My sister Almeda accompanied us – she only intends going as far as Fort Madison, Iowa. We took the little steamboat Pete Wilson at Dunnville and arrived in Reads Landing Minn. At 1 ½ oclk P.M. At 10 ½ P.M. the Northern Line Steamer “Minneapolis” T.B. Rhodes Capt Wm. W. Vandyke clerk came down from St Paul & we took passage for DuBuque Iowa. August 20th At 9 ½ P.M. we arrived in DuBuque. We went to the house of H. L. Stout Esq & found a cordial welcome. August 21st The day was warm. In the afternoon we rode out around the City with Mr. Stout. I went to the Lumber Yard Steamer Annie Girdon &c&c Sunday 22d Went to church twice to day with Mr. & Mrs. Stout. In the forenoon we heard a sermon from a stranger at the Cong. Church from the text Matt 16-26- For what shall it profit &c. In the evening we went to hear Dr. Speers at the 2d Pres. Ch. Text 2d Kings. “Is it well with thee” Monday 23d We waited all day for a boat to go down the river. No boat came much to our disappointment. We expected the City of St Paul but she was reported on the way at La Crosse for repairs. The day proved to be a very hot one. -

Cosmological Narrative in the Synagogues of Late Roman-Byzantine Palestine

COSMOLOGICAL NARRATIVE IN THE SYNAGOGUES OF LATE ROMAN-BYZANTINE PALESTINE Bradley Charles Erickson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Jodi Magness Zlatko Plese David Lambert Jennifer Gates-Foster Maurizio Forte © 2020 Bradley Charles Erickson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bradley Charles Erickson: Cosmological Narrative in the Synagogues of Late Roman-Byzantine Palestine (Under the Direction of Jodi Magness) The night sky provided ancient peoples with a visible framework through which they could view and experience the divine. Ancient astronomers looked to the night sky for practical reasons, such as the construction of calendars by which time could evenly be divided, and for prognosis, such as the foretelling of future events based on the movements of the planets and stars. While scholars have written much about the Greco-Roman understanding of the night sky, few studies exist that examine Jewish cosmological thought in relation to the appearance of the Late Roman-Byzantine synagogue Helios-zodiac cycle. This dissertation surveys the ways that ancient Jews experienced the night sky, including literature of the Second Temple (sixth century BCE – 70 CE), rabbinic and mystical writings, and Helios-zodiac cycles in synagogues of ancient Palestine. I argue that Judaism joined an evolving Greco-Roman cosmology with ancient Jewish traditions as a means of producing knowledge of the earthly and heavenly realms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my adviser, Dr. -

Piranesi's Arguments in the Carceri

ITU A|Z • Vol 15 No 3 • November 2018 • 29-39 Piranesi’s arguments in the Carceri Fatma İpek EK [email protected] • Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Yaşar University, İzmir, Turkey Received: November 2017• Final Acceptance: September 2018 Abstract Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) is an important Italian architect with his seminal theses in the debates on the ‘origins of architecture’ and ‘aesthetics’. He is numbered foremost among the founders of modern archaeology. But Piranesi was misinterpreted both in his day and posthumously. One of the most important vectors of approach yielding misinterpretation of Piranesi derived from the phe- nomenon comprising the early nineteenth-century Romanticist reception of Pi- ranesi’s character and work. Therefore, the present study firstly demonstrates that such observations derive not from an investigation of the work itself, nor from an appraisal of the historical context, but owe to the long-standing view in western culture that identifies the creator’s ethos with the work and interprets the work so as to cohere with that pre-constructed ethos. Thus the paper aims at offering a new perspective to be adopted while examining Piranesi’s works. This perspective lies within the very scope of understanding the reasons of the misinterpretations, the post-Romanticist perception of the ‘artist’, and Piranesi’s main arguments on the aesthetics, origins of architecture, and law. Keywords Carceri series, Eighteenth century discussions, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Post- doi: 10.5505/itujfa.2018.21347 doi: romanticist interpretation, Romanticist perception. 30 1. Introduction ethos. In fact, the pervasive descrip- In the architectural, historical, and tion of Piranesi’s work as cited above archaeological context of the eighteenth goes hand in hand with the descrip- century, Italian architect Giovanni Bat- tion of the biographical character as tista Piranesi (1720-1778) played an im- ‘obscure’ and ‘perverse’.3 For Piranesi’s portant role. -

Mcgilchrist and the Axial Age

Article In Search of the Origins of the Western Mind: McGilchrist and the Axial Age Susanna Rizzo 1 and Greg Melleuish 2,* 1 School of Arts & Sciences, The University of Notre Dame Australia, Cnr Broadway and Abercrombie St, P.O. Box 944, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia; [email protected] 2 School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2525, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 November 2020; Accepted: 12 January 2021; Published: 25 January 2021 Abstract: This paper considers and analyses the idea propounded by Iain McGilchrist that the foundation of Western rationalism is the dominance of the left side of the brain and that this occurred first in ancient Greece. It argues that the transformation that occurred in Greece, as part of a more widespread transformation that is sometimes termed the Axial Age, was, at least in part, connected to the emergence of literacy which transformed the workings of the human brain. This transformation was not uniform and took different forms in different civilisations, including China and India. The emergence of what Donald terms a “theoretic” culture or what can also be called “rationalism” is best understood in terms of transformations in language, including the transition from poetry to prose and the separation of word and thing. Hence, the development of theoretic culture in Greece is best understood in terms of the particularity of Greek cultural development. This transition both created aporias, as exemplified by the opposition between the ontologies of “being” and “becoming”, and led to the eventual victory of theoretic culture that established the hegemony of the left side of the brain. -

Me. in the First Place, I Did Not Subscribe for M Y Heirs And

To LADY OSSORY 15 DECEMBER 1786 547 me. In the first place, I did not subscribe for my heirs and executors,1* as it would have been, when the term of completion is twelve years henceJ4—but I am not favourable to sets of prints for authors: I scarce know above one well executed, Coypell's Don Quixote1*—but mercy on us I Our painters to design for Shakespeare! His commenta tors have not been more inadequate. Pray, who is to give an idea of Falstaffe, now Quin is dead?—and then Bartolozzi,16 who is only fit to engrave for the Pastor fido/7 will be to give a pretty enamelled fan-mount18 of Macbeth!1* Salvator Rosa might, and Piranesi20 might dash out Duncan's Castle—but Lord help Alderman Boydell21 and the Royal Academy l23 work, Messieurs Boydell also intend to HW's appreciation of Bartolozzi's success publish by subscription a series of large in the pastoral tradition, see MASON i. 386. and capital prints after pictures to be im 18. For Bartolozzi's fan mounts, see mediately painted by the following artists A. de Vesme and A. Calabi, Francesco ... Sir Joshua Reynolds [and twelve Bartolozzi, Milan, 1928, pp. 551-6, Nos others named] . To be engraved by 2216-26. Mr Bartolozzi [and eight others named]. 19. Bartolozzi engraved only one pic As soon as they have all been engraved ture, by William Hamilton, for the large they will be hung up in a gallery, built prints: Plate XXXII, for Twelfth Night, on purpose, and called the Gallery of V. -

Selective Bibliography

Selective Bibliography I. PRIMARY TEXTS Aristotle. The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation. Edited by J. Barnes. 2 vols. Bollingen Series. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984. ---. De Anima. Translated by R. D. Hicks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907. ---. De Anima. Translated by R. D. Hicks. New York: Cosimo Classics, 2008. ---.Metaphysics. Translated by William Heinemann. 2 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cam- bridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1956. ---. On the Heavens. Translated by W.K.C. Guthrie. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006. --- . On the Soul; Parva naturalia; On Breath. Translated by W.S. Hett. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957. ---. Physics, vols. I and 2. Translated by Philip Wickstead and Francis Cornford Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,1957. ---. Sophistical Refutations and The Coming to Be and Passing Away. Translated by E.S. Forster Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1955. --- . The Works of Aristotle Translated into English: De Caelo and De Generatione et Corruptione. Translated by J.L. Stocks and Harold Joachim Oxford at Clarendon Press, 1922. Celsus. On the Tme Doctrine: A Discourse Against the Christians. Translated by R. Joseph Hoffmann. Loeb Classical Library. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. Cicero. De Natura Deoru and Academica. Translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933. Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. vols. I & 2. Translated by Robert Drew Hicks. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. Epicurus. "Letter to Herodotus," in Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Trans- lated by Robert Drew Hicks. -

An Invitation from Plato: a Philosophical Journey to Knowledge

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Repository of the Freie Universität Berlin Mai Oki-Suga An Invitation from Plato: A Philosophical Journey to Knowledge Summary To trace paths to knowledge or to follow the journey searching for knowledge is to some extent equivalent to reading a philosophical book. Plato, who perceives this relation be- tween journey and philosophy, writes his dialogues as if each of his works were a journey to knowledge. This paper inquires into the ascent and descent motif that is the symbolic motion of a philosophical journey and appears in Plato’s Politeia repeatedly. By means of this motif, Plato depicts the journey of the soul in several different ways. This examination will show a possible way to read Plato’s dialogue as a philosophical journey. This journey is undertaken by Plato or the figure Socrates, but at the same time it involves its readers in philosophical inquiries. Keywords: Plato; philosophy; Republic (Politeia); journey of soul; dialogue Das Lesen eines philosophischen Buches kann in einem gewissen Sinne mit einer Weg- beschreitung oder einer Reise zum Wissen gleichgesetzt werden. Platon, der sich dieses Verhältnisses zwischen Reise und Philosophie bewusst war, verfasste seine Dialoge, als ob sie Reisen zum Wissen wären. Diese Abhandlung behandelt das Begriffspaar Aufstieg und Abstieg, das als symbolische Bewegung der philosophischen Reise in Platons Politeia mehr- mals verwendet wird. Mit diesem Motiv stellt Platon die Reise der Seele auf unterschiedli- che Weisen dar. Meine Untersuchung zeigt eine Leseweise, mit der Platons Dialog als phi- losophische Reise verstanden werden kann, die zwar von Platon oder der Figur Sokrates unternommen wird, gleichzeitig jedoch den Leser in die philosophischen Fragestellungen miteinbezieht. -

Naples, Centre of Campania Felix, Different Points of View, Changing Perspectives Through the Centuries

Naples, centre of Campania Felix, different points of view, changing perspectives through the centuries. Adriana Corrado (Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples) ‘See Naples and die’, the old cliché which has contributed to a considerable extent to the building up of an imaginary, or perhaps today one should say virtual, cultural identity for this city endowed with a dual significance. A wholly positive one, on the one hand, as a place of extreme, supreme beauty, the ideal synthesis of all that man can possibly desire, to the point of his almost gratefully accepting death, dying that is, after beholding the perfection which connotes this city. But on the other hand, an entirely negative value if one is to understand that in Naples dying comes easily and for real, be it because of illness, misery, assaults, violence, both of a moral and physical nature, gunshot wounds, or because of organised crime which in Naples is called ‘camorra’, the ragged though legitimate daughter of the Mafia, and thus no less violent. A present-day intellectual and novel writer, attentive observer of Neapolitan life, Fabrizia Ramondino, wrote in a wonderful work dedicated to her, and my, great city: “Whichever way you choose to look at her, whether you observe, watch, spy, gaze languidly, feast your eyes, peek, wink, goggle, peer, look away or even close your eyes, whether you practise clairvoyancy or voyeurism, whatever eye you choose to cast upon her is much like looking through a kaleidoscope. Shapes and meanings endlessly come together and break apart,