Performance Poetry Night

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits?

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits? Cornelia Gräbner erformance poetry in the Western world festival hall. A poem will be performed differently is a complex field—a diverse art form that if, for example, the poet knows the audience or has developed out of many different tradi- is familiar with their context. Finally, the use of Ptions. Even the term performance poetry can easily public spaces for the poetry performance makes a become misleading and, to some extent, creates strong case for poetry being a public affair. confusion. Anther term that is often applied to A third characteristic is the use of vernacu- such poetic practices is spoken-word poetry. At lars, dialects, and accents. Usually speech that is times, they are included in categories that have marked by any of the three situates the poet within a much wider scope: oral poetry, for example, or, a particular community. Oftentimes, these are in the Spanish-speaking world, polipoesía. In the marginalized communities. By using the accent in following pages, I shall stick with the term perfor- the performance, the poet reaffirms and encour- mance poetry and briefly outline some of its major ages the use of this accent and therefore, of the characteristics. group that uses it. One of the most obvious features of perfor- Finally, performance poems use elements that mance poetry is the poet’s presence on the site of appeal to the oral and the aural, and not exclu- the performance. It is controversial because the sively to the visual. This includes music, rhythm, poet, by enunciating his poem before the very recordings or imitations of nonverbal sounds, eyes of his audience, claims authorship and takes smells, and other perceptions of the senses, often- responsibility for it. -

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

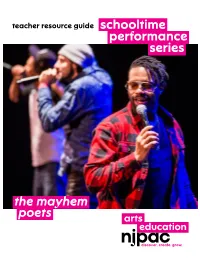

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

A Teacher's Resource Guide for the Mayhem Poets

A Teacher’s Resource Guide for The Mayhem Poets Slam in the Schools Thursday, January 28 10 a.m. Schwab Auditorium Presented by The Center for the Performing Arts at Penn State The school-time matinees are supported, in part, by McQuaide Blasko Busing Subsidy in part by the Honey & Bill Jaffe Endowment for Audience Development The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts provides season support 1 Table of Contents Welcome to the Center for the Performing Arts presentation of The Mayhem Poets ................................ 3 Pre-performance Activity: Role of the Audience .......................................................................................... 4 Best Practices for Audience Members ...................................................................................................... 4 About the Mayhem Poets ............................................................................................................................. 5 Slam poetry--the competitive art of performance poetry ............................................................................ 7 Slam Poetry--Frequently Asked Questions ............................................................................................... 8 Slam Poetry Philosophies ........................................................................................................................ 16 Taken from the website http://www.slampapi.com/new_site/background/philosophies.htm. .......... 16 Suggested Activity: Poetic Perspective ...................................................................................................... -

Art, Identity, and Status in UK Poetry Slam

Oral Tradition, 23/2 (2008): 201-217 (Re)presenting Ourselves: Art, Identity, and Status in U.K. Poetry Slam Helen Gregory Introducing Poetry Slam Poetry slam is a movement, a philosophy, a form, a genre, a game, a community, an educational device, a career path, and a gimmick. It is a multi-faced creature that means many different things to many different people. At its simplest, slam is an oral poetry competition in which poets are expected to perform their own work in front of an audience. They are then scored on the quality of their writing and performance by judges who are typically randomly selected members of the audience. The story of slam reaches across more than two decades and thousands of miles. In 1986, at the helm of “The Chicago Poetry Ensemble,” Marc Smith organized the first official poetry slam at the Green Mill in Chicago under the name of the Uptown Poetry Slam (Heintz 2006; Smith 2004). This weekly event still continues today and the Uptown Poetry Slam has become a place of pilgrimage for slam poets from across the United States and indeed the world. While it parallels poetry in remaining a somewhat marginal activity, slam has arguably become the most successful poetry movement of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Its popularity is greatest in its home country, where the annual National Poetry Slam (NPS) can attract audiences in the thousands and where it has spawned shows on television and on Broadway. Beyond this, slam has spread across the globe to countries as geographically and culturally diverse as Australia, Singapore, South Africa, Poland, and the U.K. -

Skaldic Slam: Performance Poetry in the Norwegian Royal Court

Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Skaldic Slam: Performance Poetry in the Norwegian Royal Court Anna Millward Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands December 2014 Norrænn trú Félags- og mannvísindadeild 1 Anna Millward MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis MA Kennitala: 150690-3749 Winter 2014 DEDICATION AND DISCLAIMER I owe special thanks to Prof. Terry Gunnell for his continued encouragement, help and enthusiasm throughout the process of researching and writing this dissertation. Many of the ideas put forward in this dissertation are borne out of interesting conversations and discussions with Prof. Gunnell, whose own work inspired me to take up this subject in the first place. It is through Prof. Gunnell’s unwavering support that this thesis came into being and, needless to say, any mistakes or errors are mine entirely. Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Anna Millward, 2014 Reykjavík, Ísland 2014 2 Anna Millward MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis MA Kennitala: 150690-3749 Winter 2014 CONTENTS Introduction pp. 5-13 Chapter 1. Skálds, Scholar, and the Problem of the Pen 1.1. What is Skaldic Poetry? pp. 14-15 1.2. Form and Function pp. 15-22 1.3. Preservation Context pp. 22-24 1.4. Scholarly Approaches to Skaldic Verse p. 25 1.5. Skaldic Scholarship: post-1970s pp. 26-31 1.6. Early Skaldic Scholarship: pre-1970s pp. 31-36 1.7. Skaldic as Oral Poetry, Oral Poetry as Performance pp. 36-43 1.8. -

436320 1 En Bookbackmatter 189..209

BIBLIOGRAPHY Adorno, Theodor & Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Translated by E. Jephcott, Stanford University Press, 2002. Allen, Tim & Andrew Duncan (eds.). Don’t Start Me Talking: interviews with contemporary poets. Salt, 2006. Alvarez, Al (ed.). The New Poetry. Penguin, 1966. Allnut, Gillian et al (eds). The New British Poetry. Paladin, 1988. Anderson, Simon. “Fluxus, Fluxion, Fluxshoe: the 1970s”. The Fluxus Reader, edited by Ken Friedman. Academy Editions, 1998, pp. 22–30. Andrews, Malcom. Charles Dickens and his performing selves: Dickens and public readings. Oxford University Press, 2006. Artaud, Antonin. Selected Writings, edited by Susan Sontag. Strauss & Giroux, 1976 Auslander, Philip. “On the Performativity of Performance Documentation”. After the Act—The (Re)Presentation of Performance Art, edited by Barbara Clausen. Museum Moderner Kunt Stiftung Ludwig Wien, 2005, pp. 21–33. Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words: the William Harvey James lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Claredon Press, 1975. Badiou, Alain. Being and Event. Translated by O. Feltman, Continuum, 2007. Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Translated by L. Burchill, Indiana University Press, 1984. Barry, Peter. “Allen Fisher and ‘content-specific’ poetry”. New British Poetries: The Scope of the Possible, edited by Robert Hampson & Peter Barry. Manchester University Press, 1993, pp. 198–215. ———. Contemporary British Poetry and the City. Manchester University Press, 2000. ———. Poetry Wars: British poetry of the 1970s and the battle for Earl’s Court. Salt, 2006. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 189 J. Virtanen, Poetry and Performance During the British Poetry Revival 1960–1980, Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-58211-5 190 BIBLIOGRAPHY Blanc, Alberto C. -

ENG 3062-001: Intermediate Poetry Writing Charlotte Pence Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Fall 2015 2015 Fall 8-15-2015 ENG 3062-001: Intermediate Poetry Writing Charlotte Pence Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_fall2015 Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pence, Charlotte, "ENG 3062-001: Intermediate Poetry Writing" (2015). Fall 2015. 67. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_fall2015/67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2015 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fall 2015 by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENGLISH 3062: INTERMEDIATE POETRY WRITING FALL 2015 3 CREDIT HOURS Dr. Charlotte Pence Course Information: Email: [email protected] MW 3-4:15 Office: 3745 Coleman Hall Room: CH 3159 Office Hours: MW 12:30-3 Section 001 and by appointment. REQUIRED TEXTS AND MATERIALS o The Poet’s Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry edited by Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Laux o Poetry: A Pocket Anthology, 7th Edition, Edited by R.S. Gwynn. (Bring to every class.) o The Alchemy of My Mortal Form by Sandy Longhorn ($15) o Course Packet with additional readings from Charleston Copy X, 219 Lincoln Ave. o A writer’s notebook of your choice. (Bring to every class.) o Three-ring binder or folder to keep all of the poems and handouts. COURSE DESCRIPTION Poet Richard Wilbur once remarked that “whatever margins the page might offer have nothing to do with the form of a poem.” In this intermediate course centered on the writing of poetry, we will accept Wilbur’s challenge and learn the variety of ways we can give shape to our lyrical expressions. -

Poetics of Materiality: Medium, Embodiment, Sense, and Sensation in 20Th- and 21St-Century Latin America by Jessica Elise Beck

Poetics of Materiality: Medium, Embodiment, Sense, and Sensation in 20th- and 21st-Century Latin America By Jessica Elise Becker A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Francine Masiello, Co-chair Professor Candace Slater, Co-chair Professor Natalia Brizuela Professor Eric Falci Fall 2014 1 Abstract Poetics of Materiality: Media, Embodiment, Sense, and Sensation in 20th- and 21st-Century Latin American Poetry by Jessica Elise Becker Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Francine Masiello, Co-chair Professor Candace Slater, Co-chair My approach to poetics in this dissertation is motivated by Brazilian Concrete poetry and digital writing as models for alternative textualities that reconfigure, through their material dimension, what a poem is and how we read it. These writing models also invite us to think about the ways in which cognitive and physical processes generate meaning. With these insights in mind, this dissertation returns to a broad range of so-called experimental poetry, from Hispanic American vanguardista visual poetry and Brazilian Concrete poetics to present-day Latin American media writing. By emphasizing cross-national and cross-linguistic connections, I explore poetic intersections of verbal and non-verbal modes of signifying, from non-linear poetic texts to poetic images, objects, performances, events, and processes. These different poetic movements and styles are tied together through their foregrounding of materiality, which implies a meaningful engagement with the text’s physical characteristics and with the particular medium in which texts are produced, stored, and circulated in both creative and receptive processes. -

Modern Literature: British Poetry Post-1950

This is a repository copy of Modern Literature: British Poetry Post-1950. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/140828/ Version: Accepted Version Article: O'Hanlon, K (2018) Modern Literature: British Poetry Post-1950. Year's Work in English Studies, 97 (1). pp. 995-1010. ISSN 0084-4144 https://doi.org/10.1093/ywes/may015 © The Author(s) 2018. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the English Association. This is an author produced version of a paper published in The Year's Work in English Studies. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 7. British Poetry Post-1950 2016 saw the publication of two major surveys of post-war poetry in the same series: The Cambridge Companion to British and Irish Poetry, 1945-2010, edited by Edward Larrissy, and The Cambridge Companion to British Black and Asian Literature (1945-2010), edited by Deirdre Osborne. -

American Poetry in Performance: from Walt Whitman to Hip Hop (Digitalculturebook) Online

xJPFw [Read download] American Poetry in Performance: From Walt Whitman to Hip Hop (Digitalculturebook) Online [xJPFw.ebook] American Poetry in Performance: From Walt Whitman to Hip Hop (Digitalculturebook) Pdf Free Tyler Hoffman *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3088424 in eBooks 2013-07-02 2013-07-02File Name: B00ZYLD7LY | File size: 22.Mb Tyler Hoffman : American Poetry in Performance: From Walt Whitman to Hip Hop (Digitalculturebook) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised American Poetry in Performance: From Walt Whitman to Hip Hop (Digitalculturebook): 0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy CustomerBrand new0 of 8 people found the following review helpful. much is missingBy Janek JaneczukThere are a few foundational books I want to recommend first regarding the history of performance/literary theater: Towards a Poor Theatre (Theatre Arts (Routledge Paperback))primarily Grotowski, linked here. In an age of excess and spectacle Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle as described by Hedges in the book I linked, we have lost all sense of humanity along with common sense. Look at the extreme greed of global capitalists and the debates from "conservative" Republicans in the U.S. running for president where Christian values take a backseat to politicized religious ideology. "Humanity suffers when The Many suffer for the wealth of a elite few." I'm quoting poet Hedwig Gorski whose book linked here documents Intoxication: Heathcliff on Powell Street how they put Grotowski's Poor Theater into practice in the 1970s in a skewed way, maybe a sloppy American way compared to the long traditions of Polish theatre. -

A Brief Guide to Slam Poetry

A Brief Guide to Slam Poetry A Brief Guide to Slam Poetry Because Allen Ginsberg says, "Slam! Into the Mouth of the Dharma!" Because Gregory Corso says, "Why do you want to hang out with us old guys? If I was young, I'd be going to the Slam!" Because Bob Kaufman says, "Each Slam / a finality." --Bob Holman, from "Why Slam Causes Pain and Is a Good Thing" One of the most vital and energetic movements in poetry during the 1990s, slam has revitalized interest in poetry in performance. Poetry began as part of an oral tradition, and movements like the Beats and the poets of Negritude were devoted to the spoken and performed aspects of their poems. This interest was reborn through the rise of poetry slams across America; while many poets in academia found fault with the movement, slam was well received among young poets and poets of diverse backgrounds as a democratizing force. This generation of spoken word poetry is often highly politicized, drawing upon racial, economic, and gender injustices as well as current events for subject manner. A slam itself is simply a poetry competition in which poets perform original work alone or in teams before an audience, which serves as judge. The work is judged as much on the manner and enthusiasm of its performance as its content or style, and many slam poems are not intended to be read silently from the page. The structure of the traditional slam was started by construction worker and poet Marc Smith in 1986 at a reading series in a Chicago jazz club. -

Performance of Poeticity: Stage Fright and Text Anxiety in Dutch Performance Poetry Since the 1960S

The Performance of Poeticity: Stage Fright and Text Anxiety in Dutch Performance Poetry since the 1960s GASTON FRANSSEN Abstract: The relation between performance poetry and poetry criticism, as the latter is generally practiced in newspapers and journals, appears to be strained. This is the result of a clash between two different performance traditions: on the one hand, a tradition that goes back to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century conventions of poetry declamation or recitation; and on the other hand, a tradition based on performance experiments carried out by avant-garde movements during the first half of the twentieth-century. This article charts the different sets of expectations associated with these traditions by analyzing how these expectations became manifest during the Dutch poetry event ‘Poëzie in Carré’ (Febraury 28th, 1966). As will become clear, individual authorship, textual unity, and poetic significance play important, yet very different roles in these two traditions. Furthermore, I put forward an alternative approach to the issue at hand, by focusing on one particular participant in ‘Poëzie in Carré,’ Johnny van Doorn (1944-1991). Thus, this article aims to contribute to a historically aware and more constructive analysis of performance poetry. Contributor: Gaston Franssen is Assistant Professor in Literature & Diversity at the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. In 2008, he published Gerrit Kouwenaar en de politiek van het lezen (Nijmegen: Vantilt), an analysis of the interpretive conventions at work in Dutch poetry criticism. His research topics include modern Dutch and English literature, authorship, literary celebrity, and the relation between fiction and transgression. The increasing visibility of performance poetry in the literary field of the Netherlands since the 1960s has resulted in a deadlock in Dutch literary criticism.