Modern Literature: British Poetry Post-1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quest Motif in Snyder's the Back Country

LUCI MARÍA COLLIN LA VALLÉ* ? . • THE QUEST MOTIF IN SNYDER'S THE BACK COUNTRY Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentração em Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federal ' do Paraná, para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Letras. Orientador: Profa. Dra. Sigrid Rénaux CURITIBA 1994 f. ] there are some things we have lost, and we should try perhaps to regain them, because I am not sure that in the kind of world in which we are living and with the kind of scientific thinking we are bound to follow, we can regain these things exactly as if they had never been lost; but we can try to become aware of their existence and their importance. C. Lévi-Strauss ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to acknowledge my American friends Eleanor and Karl Wettlaufer who encouraged my research sending me several books not available here. I am extremely grateful to my sister Mareia, who patiently arranged all the print-outs from the first version to the completion of this work. Thanks are also due to CAPES, for the scholarship which facilitated the development of my studies. Finally, acknowledgment is also given to Dr. Sigrid Rénaux, for her generous commentaries and hëlpful suggestions supervising my research. iii CONTENTS ABSTRACT vi RESUMO vi i OUTLINE OF SNYDER'S LIFE viii 1 INTRODUCTION 01 1.1 Critical Review 04 1.2 Cultural Influences on Snyder's Poetry 12 1.2.1 The Counter cultural Ethos 13 1.2.2 American Writers 20 1.2.3 The Amerindian Tradi tion 33 1.2.4 Oriental Cultures 38 1.3 Conclusion 45 2 INTO THE BACK COUNTRY 56 2.1 Far West 58 2.2 Far East 73 2 .3 Kail 84 2.4 Back 96 3 THE QUEST MOTIF IN THE BACK COUNTRY 110 3.1 The Mythical Approach 110 3.1.1 Literature and Myth 110 3 .1. -

The Force of Poetry, 1987, Christopher Ricks, 019282046X, 9780192820464, Oxford University Press, 1987

The Force of Poetry, 1987, Christopher Ricks, 019282046X, 9780192820464, Oxford University Press, 1987 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1UaWeNM http://goo.gl/RoskD http://www.amazon.com/s/?url=search-alias=stripbooks&field-keywords=The+Force+of+Poetry "As critic and scholar he calls tremendously on his knowledge of literature past and present to provide new insights, aspects and illuminations....Ricks looks at poetry over a considerable range, a lively critic who assures us through clarifying analysis of its power and force in our lives."--The New York Times Book Review. "A work of enormous brilliance."--Encounter. "The richness and variety of these essays is truly remarkable."--Listener. Though published independently over many years, each of these penetrating essays asks how a poet's words reveal "the force of poetry"--that force, in Dr. Johnson's words, "which calls new powers into being, which embodies sentiment, and animates matter." The poets treated here range from John Gower to Robert Lowell, and include Marvell, Milton, Johnson, Wordsworth, Philip Larkin, and Geoffrey Hill. Ricks has also added four essays on general topics: on cliches, on lies, on misquotations, and on American literature in its relation to the transitory. The Force of Poetry reveals the quality of Ricks's criticism that W.H. Auden responded to when he described him as "exactly the kind of critic every poet dreams of finding." DOWNLOAD http://wp.me/2ZsqO http://bit.ly/1n2tB4N A. E. Housman a collection of critical essays, Christopher B. Ricks, 1968, Literary Criticism, 182 pages. The beginnings of modern poetry , Herbert Walter Piper, 1967, Poetry, 161 pages. -

Christopher Ricks

CHRISTOPHER RICKS Christopher Ricks has been an officer in the Green Howards, a scholar of Balliol, a Fellow of Worcester, Professor of English at Bristol, King Edward VII Professor at Cambridge, and is now Warren Professor of Humanities at Boston University, Co- Director of its Editorial Institute, and a Fellow of the British Academy. He is a scholar, critic and teacher of enormous distinction, who has a uniquely subtle critical imagination, a graceful, sensitive and stringent intelligence, which, allied with his profound scholarship, makes him an unrivalled lecturer. A lecture by Christopher Ricks is always an exciting, inspiring event. His review of Seamus Heaney’s Death of a Naturalist in the New Statesman helped to launch Heaney’s career, and his review of Philip Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings in the New York Review of Books helped to win a North American readership for Larkin’s poems. He has written with great insight and intelligence about Paul Muldoon in a compelling essay on Andrew Marvell in The Force of Poetry, and as his recent study of Bob Dylan, Dylan’s Visions of Sin, shows he is keenly aware of popular culture. His critical study, Milton’s Grand Style (1963) challenged the surprisingly successful attempt of Eliot and Leavis to downgrade Milton’s poetry, and initiated the critical and scholarly reclaiming of Milton’s work which has taken place over the last four decades. He has also published Tennyson (1972), Keats and Embarrassment (1974), The Force of Poetry (1984), T.S. Eliot and Prejudice (1988), Allusion to the Poets (2002), Dylan’s Visions of Sin (2003).He has published two anthologies: The New Oxford Book of Victorian Verse (1987) and The Oxford Book of English Verse (1999). -

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits?

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits? Cornelia Gräbner erformance poetry in the Western world festival hall. A poem will be performed differently is a complex field—a diverse art form that if, for example, the poet knows the audience or has developed out of many different tradi- is familiar with their context. Finally, the use of Ptions. Even the term performance poetry can easily public spaces for the poetry performance makes a become misleading and, to some extent, creates strong case for poetry being a public affair. confusion. Anther term that is often applied to A third characteristic is the use of vernacu- such poetic practices is spoken-word poetry. At lars, dialects, and accents. Usually speech that is times, they are included in categories that have marked by any of the three situates the poet within a much wider scope: oral poetry, for example, or, a particular community. Oftentimes, these are in the Spanish-speaking world, polipoesía. In the marginalized communities. By using the accent in following pages, I shall stick with the term perfor- the performance, the poet reaffirms and encour- mance poetry and briefly outline some of its major ages the use of this accent and therefore, of the characteristics. group that uses it. One of the most obvious features of perfor- Finally, performance poems use elements that mance poetry is the poet’s presence on the site of appeal to the oral and the aural, and not exclu- the performance. It is controversial because the sively to the visual. This includes music, rhythm, poet, by enunciating his poem before the very recordings or imitations of nonverbal sounds, eyes of his audience, claims authorship and takes smells, and other perceptions of the senses, often- responsibility for it. -

Literary Scholars Association Critics

The 14th Annual Conference of The Association of October 24-26, 2008 Literary Scholars Sheraton Society Hill Hotel Critics and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Literature Titles from Oxford Journals www.adaptation.oxfordjournals.org www.camqtly.oxfordjournals.org www.english.oxfordjournals.org www.alh.oxfordjournals.org www.cww.oxfordjournals.org ADAPTATION AMERICAN LITERARY THE CAMBRIDGE CONTEMPORARY ENGLISH Adaptation provides an HISTORY QUARTERLY WOMEN’S WRITING Published on behalf of international forum to Covering the study of US The Cambridge Quarterly CWW assesses writing The English Association, theorise and interrogate the literature from its origins was established on the by women authors from English contains essays phenomenon of literature through to the present, principle that literature is an 1970 to the present. It on major works of English on screen from both a American Literary History art, and that the purpose of reflects retrospectively on literature or on topics of literary and film studies provides a much-needed art is to give pleasure and developments throughout general literary interest, perspective. forum for the various, enlightenment. It devotes the period, to survey the aimed at readers within often competing voices itself to literary criticism variety of contemporary universities and colleges of contemporary literary and its fundamental aim work, and to anticipate and presented in a lively inquiry. is to take a critical look at the new and provocative and engaging style. accepted views. women’s writing. www.fmls.oxfordjournals.org -

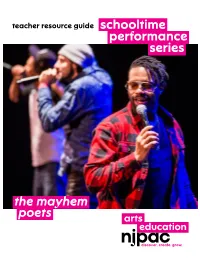

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

Download a PDF File of the Index for Volume 40

Aindex to Volume 40 – 2018 Compiled by H.e. Knox Z INDEX Index of Authors: books reviewed are listed by author, with the title in italics and the reviewer’s name in brackets, followed by the issue number. Index of Reviewers: books reviewed are listed by reviewer, with the author’s name after the title. Subject Index: the subject is followed by the title and author of the book discussed, with the reviewer’s name in brackets. ‘Corres.’ refers to letters sent to the editor in response to the article listed, and printed in subsequent issues. Index of Original Contributions: all articles which are not strictly book reviews (features, diaries, poems, short stories) are listed here, as well as appearing in the index of authors. Index of Authors Adam, G.: Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Berlin, L.: Cixin Liu: Market in the 21st Century. (Abrahamian, A.A.) 40.9 Evening in Paradise: More Stories. (Lockwood, P.) 40.23 Translator Liu, K. Adams, M.: Ælfred’s Britain: War and Peace in the Viking Age. Welcome Home: A Memoir with Selected Photographs. The Dark Forest. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 (Shippey, T.) 40.9 (Lockwood, P.) 40.23 Death’s End. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 Ahmed, S.: Living a Feminist Life. (Rose, J.) 40.4 Bermant, A.: Margaret Thatcher and the Middle East. The Three-Body Problem. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 Akomfrah, J.: Mimesis: African Soldier. (Harding, J.) 40.23 (Wheatcroft, G.) 40.17 The Wandering Earth. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 Alderton, D.: Everything I Know about Love. -

165Richard.Pdf

165 165 c2001 Richard Caddel Basil Basil Bunting : An Introduction to to a Northern Modernist Poet : The Interweaving Voices of Oppositional Poetry Richard Richard Caddel I'd I'd like to thank the Institute of Oriental and Occidental Studies for inviting me to give this this presentation, and for their generosity in sustaining me throughout this fellowship. I have have to say that I feel a little intimidated by my task here, which is to present the work of of a poet who is still far from well known in his own country, and who many regard as not not an easy poet (is there such a thing?) in an environment to which both he and I are foreign. foreign. This is my first visit to your country, and Bunting, though he travelled widely throughout throughout his life, never came here. That's a pity, because early in his poetic career he made what I consider to be a very effective English poem out of the Japanese prose classic, classic, Kamo no Chomei's Hojoki (albeit from an Italian tranlation, rather than the original) original) and I think he had the temperament to have enjoyed himself greatly here. I'm I'm going to present him, as much as possible, in his own words, often using recordings of him reading. He read well, and his poetry has a direct physical appeal which makes my task task of presenting it a pleasure, and I hope this approach will be useful for you as well. But first a few introductory words will be necessary. -

Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics

Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics Series Editor Rachel Blau DuPlessis Temple University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics promotes and pursues topics in the burgeoning field of 20th and 21st century poetics. Critical and scholarly work on poetry and poetics of interest to the series includes social location in its relationships to subjectivity, to the construction of authorship, to oeuvres, and to careers; poetic reception and dissemination (groups, movements, formations, institutions); the intersection of poetry and theory; questions about language, poetic authority, and the goals of writing; claims in poetics, impacts of social life, and the dynamics of the poetic career as these are staged and debated by poets and inside poems. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14799 Luke Roberts Barry MacSweeney and the Politics of Post-War British Poetry Seditious Things Luke Roberts King’s College London London, United Kingdom Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics ISBN 978-3-319-45957-8 ISBN 978-3-319-45958-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45958-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017930177 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC OCCASIONAL LIST: DECEMBER 2019 P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. AGEE, James. The Morning Watch. 8vo, original printed wrappers. Roma: Botteghe Oscure VI, 1950. First (separate) edition of Agee’s autobiographical first novel, printed for private circulation in its entirety. One of an unrecorded number of offprints from Marguerite Caetani’s distinguished literary journal Botteghe Oscure. Presentation copy, inscribed on the front free endpaper: “to Bob Edwards / with warm good wishes / Jim Agee”. The novel was not published until 1951 when Houghton Mifflin brought it out in the United States. A story of adolescent crisis, based on Agee’s experience at the small Episcopal preparatory school in the mountains of Tennessee called St. Andrew’s, one of whose teachers, Father Flye, became Agee’s life-long friend. Wrappers dust-soiled, small area of discoloration on front free-endpaper, otherwise a very good copy, without the glassine dust jacket. Books inscribed by Agee are rare. $2,500.00 2. [ART] BUTLER, Eugenia, et al. The Book of Lies Project. Volumes I, II & III. Quartos, three original portfolios of 81 works of art, (created out of incised & collaged lead, oil paint on vellum, original pencil drawings, a photograph on platinum paper, polaroid photographs, cyanotypes, ashes of love letters, hand- embroidery, and holograph and mechanically reproduced images and texts), with interleaved translucent sheets noting the artist, loose as issued, inserted in a paper chemise and cardboard folder, or in an individual folder and laid into a clamshell box, accompanied by a spiral bound commentary volume in original printed wrappers printed by Carolee Campbell of the Ninja Press. -

John MUCKLE London Brakes

John Muckle was born in the village of Cobham, Surrey, but lived most of his adult life in Essex and London. Amongst other things he has been a copywriter, an editor, a lecturer, a careworker, a book- shop assistant, a library assistant, a freelance writer and a motorcycle courier. In the 1980s he initiated the Paladin Poetry Series and was General Editor of its flagship anthology,The New British Poetry (Paladin, 1988). His previous books include The Cresta Run (short stories), Cyclomotors (a novella with photographic illustrations), and Firewriting and Other Poems (Shearsman Books, 2005). Also by John Muckle Poetry It Is Now As It Was Then (with Ian Davidson) Firewriting and Other Poems Prose The Cresta Run Bikers (with Bill Griffiths) Cyclomotors As General Editor: The New British Poetry (eds., Allnutt, D’Aguiar, Edwards, Mottram) John Muckle London Brakes a novel Shearsman Books Exeter Published in the United Kingdom in 2009 by Shearsman Books 58 Velwell Road Exeter EX4 4LD ISBN 978-1-84861-101-6 First Edition Copyright © John Muckle, 2009. The right of John Muckle to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act of 1988. All rights reserved. Acknowledgements Excerpts from this novel were originally published in Bazzin’ (Tony Baker), Infolio (Tom Raworth) and in Bikers (with poems by Bill Griffiths, Amra Imprint, 1990). With thanks to Dave Cook, Tony Frazer, Chris Noble, Martin Stott — and for Robert. I wish to gratefully acknowledge a Hawthornden Fellowship that was helpful in the early stages of writing this novel. -

Lee Harwood the INDEPENDENT, 5TH VERSION., Aug 14Odt

' Poet and climber, Lee Harwood is a pivotal figure in what’s still termed the British Poetry Revival. He published widely since 1963, gaining awards and readers here and in America. His name evokes pioneering publishers of the last half-century. His translations of poet Tristan Tzara were published in diverse editions. Harwood enjoyed a wide acquaintance among the poets of California, New York and England. His poetry was hailed by writers as diverse as Peter Ackroyd, Anne Stevenson, Edward Dorn and Paul Auster . Lee Harwood was born months before World War II in Leicester. An only child to parents Wilfred and Grace, he lived in Chertsey. He survived a German air raid, his bedroom window blown in across his bed one night as he slept. His grandmother Pansy helped raise him from the next street while his young maths teacher father served in the war and on to 1947 in Africa. She and Grace's father inspired in Lee a passion for stories. Delicate, gentle, candid and attentive - Lee called his poetry stories. Iain Sinclair described him as 'full-lipped, fine-featured : clear (blue) eyes set on a horizon we can't bring into focus. Harwood's work, from whatever era, is youthful and optimistic: open.' Lee met Jenny Goodgame, in the English class above him at Queen Mary College, London in 1958. They married in 1961. They published single issues of Night Scene, Night Train, Soho and Horde. Lee’s first home was Brick Lane in Aldgate East, then Stepney where their son Blake was born. He wrote 'Cable Street', a prose collage of location and anti fascist testimonial.